There is a hierarchy of language. This is true for secular politics and cultural commerce, as well as in terms of religion. In this hierarchy, some languages are higher than others.

JRR Tolkien, a philologist at Oxford, was quite aware of this. In his fictional world, which we know through Lord of the Rings, the elves speak the high elvish language called Quenya. Further, Quenya is divided into two parts: the Parmaquesta is a classical “book language” that preserved writing, while the Tarquesta is the high speech used in formal occasions. The opposite of this high language is the Black Speech of Mordor, a debased language that only orcs and the wearer of the One Ring can understand.

Frank Herbert’s Dune also has its share of languages, each serving a different purpose. Galach is the Imperium’s official language, and it is the most widely spoken tongue in the known universe. Other, less official languages and dialects exist for different purposes, such as secret sects, battle, and formal occasions. In the hit 1990s science fiction drama Babylon 5, the Narn ambassador, G’Kar of the Kha’ri, says the following of the Holy Book of G’Quan: “Sacrilege! It must be read in the mother tongue or not at all!” (As for the Star Trek universe, while there is an entire Klingon language available – enough for the existence of Klingon Shakespearean theater – there are no high languages. So much for depth in Star Trek.)

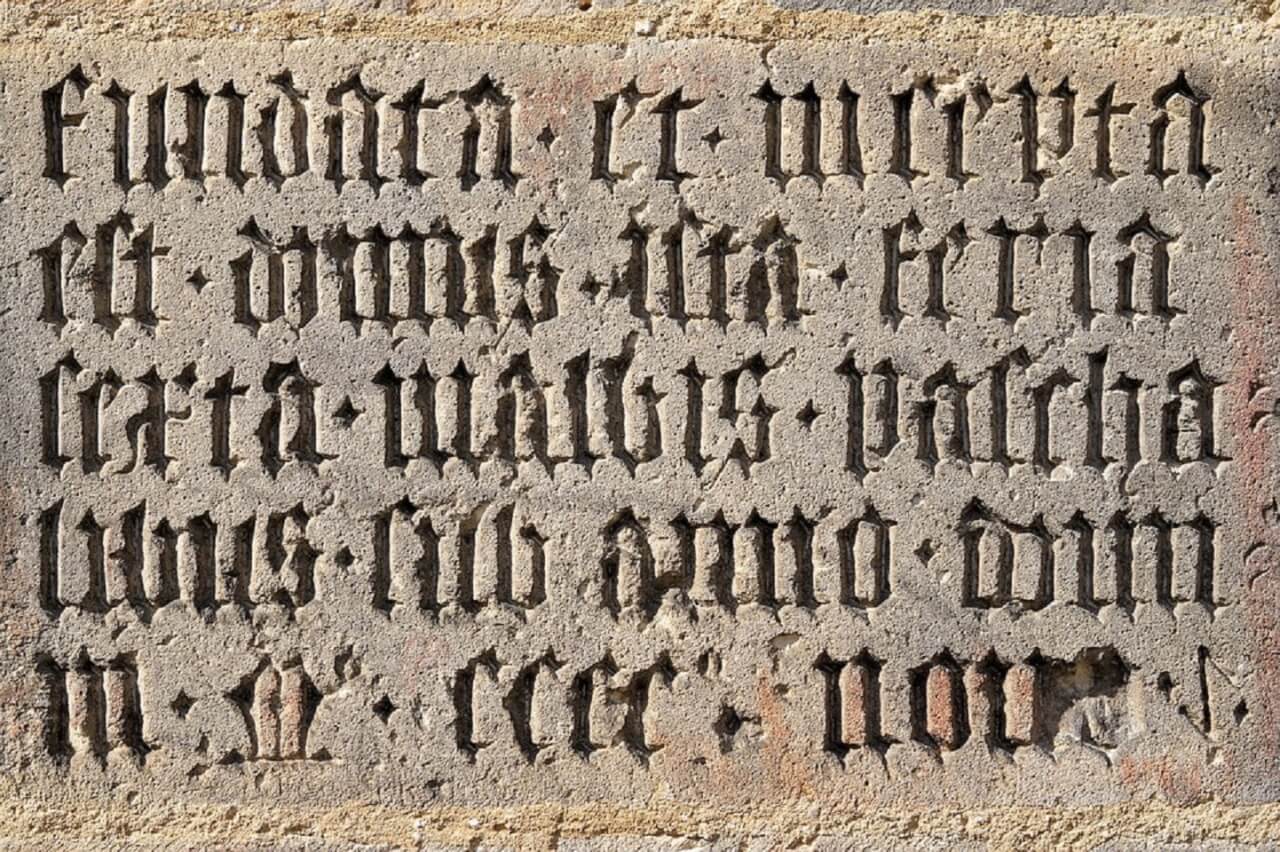

The idea of high languages is not a new phenomenon. High language and the hierarchy of language were not a spontaneous invention that popped up out of nowhere shortly after Archbishop Lefebvre founded the Society of Saint Pius X. The primacy of Latin has been known since medieval times, and its place in the hierarchy of language has been a source of inspiration.

When it comes to Catholicism, Latin is supreme. Latin is the language of the Church. James Gibbons once said that while our faith is the jewel, Latin is the casket that contains it: “So careful is the Church of preserving the jewel intact that she will not disturb even the casket in which it is set.”

Many disagree with this notion. Some people think one language is just as good as another. Others think the most current vernacular language is the best for the current times. These people disagree with the idea of a hierarchy of languages.

Yet there are some who acknowledge the hierarchy of languages. Latin’s supremacy is real, and its primacy should be defended just as much as the Hebrews would have defended the Ark of the Covenant.

Pleasing God with the Best

It would not be right if I failed to mention the practical reasons for using Latin.

Many would argue that most people do not understand Latin. Even the TLM laity, it could be argued, do not understand Latin. Perhaps Latin was the lingua franca of an earlier age, but not now. And yet Latin is the Church’s living language.

One would argue that Latin is not useful because no one understands it. Critics would argue that we get no utility out of it and that having a Mass in Latin serves only to fill the pride of cultural snobs. Catholics, however, are not materialist utilitarians. Nor are the prayers in a Mass for us. Our prayers are for God. God is the audience in a Mass. We attend Mass not to be served, nor to celebrate ourselves, as James Gibbons explains:

Now, what is the Mass? It is not a sermon, but it is a sacrifice of prayer which the Priest offers up to God for himself and the people. When the Priest says Mass he is speaking not to the people, but to God, to whom all languages are equally intelligible.

Also, assuming that the Mass is being said reverently – with the priest not putting on a Broadway show – and the priest faces the tabernacle ad orientem and speaks in prayerful undertones, the congregation isn’t even going to be hearing much of what the priest says in the first place. We are all to be facing God, are we not?

Arguably as well, just giving up on Latin and giving in to praying in the vernacular is lazy. It takes effort to pray the Mass in Latin, and this is one of the reasons why Latin is arguably more pleasing to God than a vernacular language. Another analogy could be this: that there is more dignity in using a golden chalice for the wine-turned-Blood than there is in using a paper cup. Putting effort into our prayers is efficacious and good. Is God not worth the effort? Or are we too weak, apathetic, and desiring of convenience to worship God in an elevated way?

Latin’s Practicality

“Latin’s a dead language!” This is true. This is a good thing, too. Latin words will not change their meaning, because common use of the language halted so long ago. With Latin, there is no danger of subtle mutations muddying the waters of understanding. Veterum Sapientia reminds us that Latin’s “‘concise, varied and harmonious style, full of majesty and dignity’ makes for singular clarity and impressiveness of expression.” And seeing as how the Church is destined to survive until the end of the world, “its very nature requires a language which is universal, immutable, and non-vernacular.”

Speaking of being universal, many people who are old enough will recount the days before Vatican II when they could go anywhere in the world and attend a Mass in its universal language. In those days, the Mass was the same no matter where you went. It was truly universal – not the diced up Babel-like wreck that it is now. With Latin as the Church’s universal language, you could go to Mass anywhere and not feel anxiety. Now? If you leave your home parish – or go to another country, for that matter – you have no idea what you’re walking in to.

More than all of this, it is important to have a language of the Church to unite its people. In countries with different dialects, the use of an official language for formal occasions exemplifies cultural unity. The use of a singular formal language shows pride in that country’s heritage and cultural identity. This idea is not lost on other denominations or religions. For example, rabbis will read their prayers in Hebrew. In other rites, old Slavonic or Greek is used. So, too, does the Catholic Church possess her own mother tongue, which is Latin. Why throw away one’s heritage?

Sacraments vs. “Sacramental” the Noun vs. “Sacramental” the Adjective

Latin is not a sacrament. It is not technically a sacramental – though perhaps one day it will be recognized as such. However, the Latin language is sacramental, as an adjective, in its nature.

The seven sacraments were instituted by Christ, and there will be no addition to them. As for sacramentals, we are told in the Catechism that they do not confer the grace of the Holy Spirit in the same way as the sacraments. Yet they prepare us to receive grace and dispose us to cooperate with it. A sacramental is something that extends the liturgical life of the Church. It is a sacred sign instituted by the Church that manifests the respect due to the sacraments, and it secures the sanctification of the faithful.

Latin does all of this.

Furthermore, Pope John XXIII attests that Latin, the noble and majestic language of the Church, has been “consecrated through constant use by the Apostolic See.” In a Mass, everything is to be set apart and consecrated for the prayers to God, and Latin is no exception. This elevated, sacral language inspires inner stillness and prayerfulness. The Latin language veils the liturgical realm from the rest of the world, just as priests of the Old Testament era sacrificed and prayed in a sanctuary while the people prayed at a distance in the court.

The Catechism tells us that sacramentals respond to the needs, culture, and special history of Christians in a particular region or time. It is easily arguable that the unifying, rallying stability of Latin is needed in the Catholic Church at this time in history more than any other.

The Catholic Encyclopedia states that “the sacramentals help to distinguish the members of the Church from heretics, who have done away with the sacramentals or use them arbitrarily with little intelligence.”

Can it be disputed that now, more than ever, we need to distinguish who is still faithful to the Catholic Church? Sacramentals help us to make such distinctions – as does the use of Latin. Latin shares a special place in the highest functions of Catholicism.

Finally, Latin – like the sacramentals – is a kind of an object of benediction that has particular effects. Like holy water, Latin not only prepares our hearts for Mass, but is even capable of driving away evil spirits. This has been documented by several exorcists, and most of them will agree on Latin’s effects on the demons. For example, Blessed Mary of Jesus Crucified was once possessed by the devil in 1870 for forty days. After the exorcist told the demon to speak Latin, he hesitated and left, saying the Latin “was against me.” The simple fact is that Latin is much more effective in driving away demons than the vernacular, once more attesting to Latin’s high place in the hierarchy of language – in both this world and perhaps the next.

Conclusion

There truly is a hierarchy of languages. At least in the Church, it was not up until the 20th century that leaders decided to ignore this fact. When the Mass is spoken in Latin, we are offering God our best. We do not come to Him with vulgar, low slang. We pray to him in a high speech. Latin is immutable, unchangeable – as God is – and can be relied upon to precisely convey our intentions to God in prayer. It is dependably universal, uniting, and unconfusing. Latin is the language of the Catholics.

The high language of the Church prepares our souls and expresses our prayers elegantly. It is the most efficacious language, and those who have invested their lives in attending the Latin Mass will attest to its tangible effects. Latin’s nature is quite sacramental, and its effects share those of actual sacramentals. It is not out of the question to consider that, after this crisis in the Church is over, Latin itself will become categorized as a sacramental.

Throwing away Latin for the vernacular is the equivalent of burning down an inheritance. To lazily settle for the vernacular is to be like a man renouncing his national heritage. It is to exchange gold for paper. It is to show up for a coronation wearing torn jeans, sandals, and a t-shirt. Latin is far from the malleable, everyday vernacular used in other societies. To cast it aside will only have spiritually dysgenic effects on future Christians, who will find themselves inheriting far less than their predecessors.