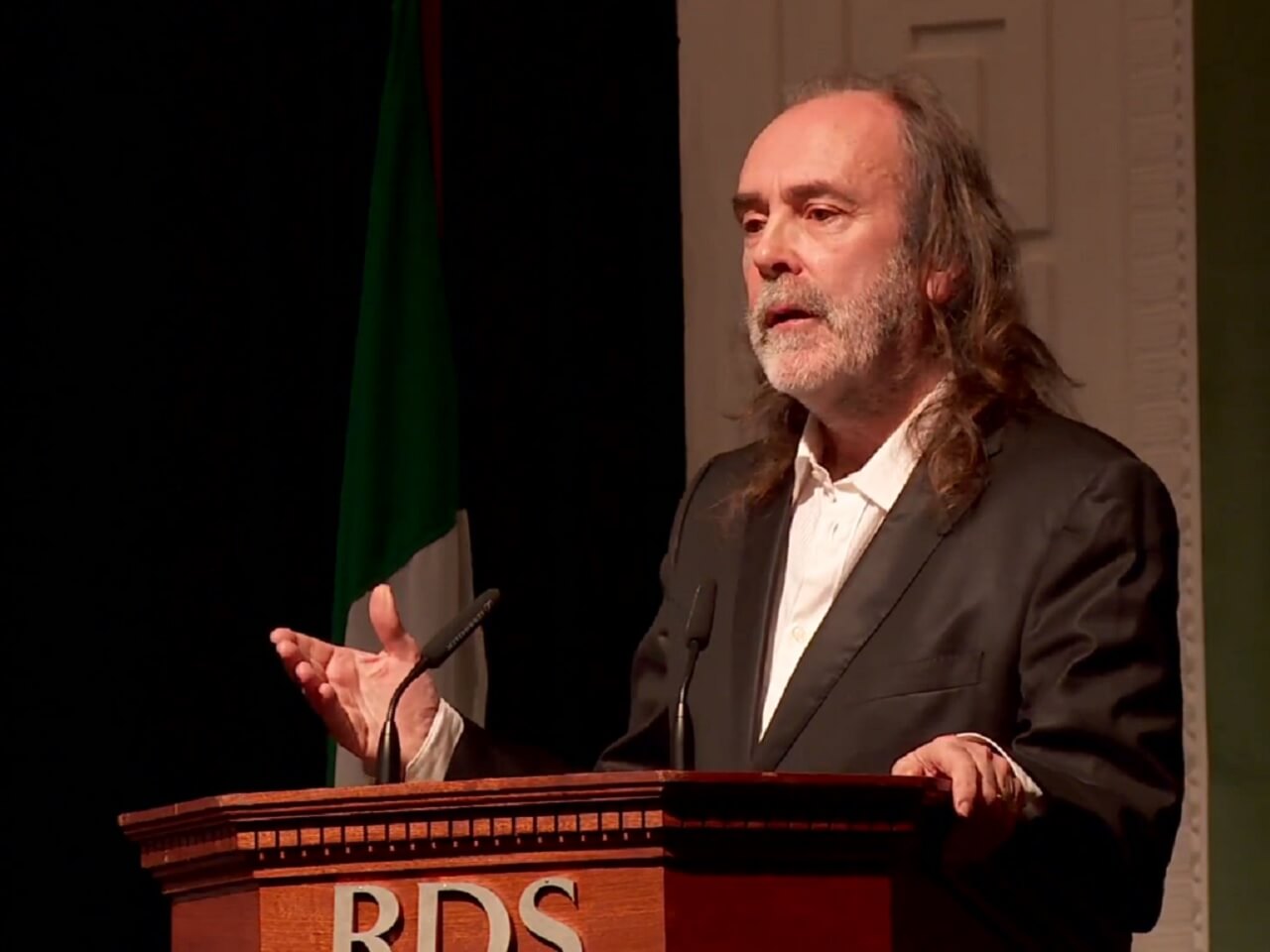

When a maverick journalist opposes popular opinion, at least as promoted by prominent media, what happens next? For rock critic turned cultural commentator John Waters, it’s condemnation followed by self-imposed exile from Dublin’s left-liberal, bien-pensant paper-of-record, The Irish Times.

This unrepentant dissident, not to be confused by Americans with Baltimore’s cult icon and iconoclastic filmmaker, defends his patch of emerald turf against our new world order — not (only) that of the Bushes, but of those who banish any trace of transcendence. As a longtime correspondent, Waters speaks for a “Peter Pan generation” who entered a dream-scape never glimpsed by their progenitors. Born in 1955, he and his peers from the 1960s through ’80s found themselves, boosted by a Celtic Tiger economic engine, “as foreigners working from home and emigrants in our own land.” They ushered in an “unassailable” secular agenda, rejecting Catholic, communal, rural-dominant mores once and for all.

John Waters continues his assault on post-Christian Ireland in Give Us Back the Bad Roads, his ninth book (2019). His first, a surprise bestseller, Jiving at the Crossroads (1990), roughly coincided with his father’s death. The period since both events unfolds in fits and starts, as the son addresses that humble mail coach–driver in a small town in Co. Roscommon, who taught him the value of manual labor and the trust in tradition. (As a relevant aside, to show how small Ireland’s networks of who-knows-whom remain, my family at their farmhouse — now abandoned, as all my relatives emigrated — would have gotten their post delivered by Waters and son, near the first village north of their own market-town.)

John’s career began covering music gigs for Hot Press, an upstart newspaper whose emergence proved well timed with the punk explosion, hedonistic excess, and the demands of those raised in the wake of Vatican II to become not “the pope’s children” addressed by John Paul II in his hyped 1979 tour, but a generation freed from clerical submission, censored expression, and class-bound economic stagnation.

The results of this leap into liberation led not to freedom but to incarceration within a cunning and callow bureaucracy bent on enforcing standards of a politically correct generation, his mates and heirs.

This blowback fuels Waters’s longstanding determination in print and by his own interventions with similarly suffering fellow Irish families to defend the “blood link” of relationships against referenda on “divorce-by-demand,” government intervention in the cause of “children’s rights,” same-sex marriage, and legal abortion. Quixotic as this principled opposition remains in Ireland’s Anglo-Americanized monoculture demolishing its customary “moral paradigm” that a younger, brash, “up from the country” Waters had volunteered to undermine, his mature self favors “common sense.” Although caricatured as a Catholic bigot by his former colleagues — “hired guns” — and their “progressive” political-clerical cronies, Waters grounds his critique against imposition of consumerism and corporate “rewards.”

These have obliterated his father’s craft and his native town’s legacy of community, sly solidarity, and respect for humble dignity. Waters witnesses the transition from his job as a railway clerk to those he and his eager counterparts sought as if Euro-topia at last, but winding up a “screen slave” or a “cubicle hostage.” The trajectory Waters has mapped in his seven intervening books gradually finds its aim. He tires of the distracted, profit-mad, sex- and drug-addled consumerism aided and abetted by his cohort.

Waters’s focus, despite the repetitions (common, as his many collections blending reporting, research, memoir, and cultural critique often resurrect his past and present predicaments as a prophet without honor in his homeland) sharpens. Returning to his paternal townland in a “strange collision of farmland and wilderness” overlooking Ben Bulben on the Atlantic shore (and Yeats’s grave), John Waters watches turf “smoulder like Gabriel Byrne.” Bent on avoiding school on Monday, he had tried to “concentrate like Uri Geller until I conjured up a pain in my stomach.” Tellingly, Waters warns of what will transpire if the embattled “capacity to be human” gets trodden down by an Irish mob sworn to steamroller the valuable contributions of a tradition rooted in centuries of hard-won verities rather than clogged with the media’s “effluent and lies.” Waters imagines a lawn laid atop a yard of concrete: “it may briefly give the impression of health, but eventually, for obvious reason, it withers away.” Without a “consciousness of the absolute,” people will fail to nourish a mentality devoid of religion and dismissive of this venerable “public expression of the total dimension of human nature.”

Waters’s reversion to a measure of Catholic practice emerged gradually. He attended traditional Latin Mass services held at St. Kevin’s in Dublin, which were approved back in 2007. He concludes Lapsed Agnostic (2008) by documenting his growing attraction to the conservative, post-conciliar successor to Italy’s Catholic Action, Fr. Luigi Guissani’s Community and Liberation movement. Since early 2017, he contributes regularly to First Things. Last autumn, he was featured in E. Michael Jones’s Culture Wars. However, a careful parsing of John Waters’s writing presents his quest as one driven arguably far more by his own standards for uncompromising truth than by any dogma. As he asks: what happens when a third generation in Ireland, and by extension the formerly catechized realms across the world, matures with no exposure to the Faith? What follows for Ireland when the “don’ts” of Catholicism fade away?

These questions merit wise responses. Many who serve as leaders in the alternative Catholic media enter from other denominations or perhaps none. Yet intelligent and articulate insights from those left adrift in the last fifty-odd years, brought up in families still faithful but who themselves fell away suddenly or slowly, often gain less vocal attention or press promotion. John Waters’s halting pilgrimage away from progressive piety might, thus, be guided well by an exchange from a once “center-left” Italian colleague in the Fourth Estate, Aldo Maria Valli (b. 1958), and composer-liturgist Aurelio Porfiri (b. 1968). Their narrative, translated last year as Uprooted: Dialogues in a Liquid Church, remains rare, in that it’s written by cradle Catholics too young to remember the Latin Mass as it was with any firm memories but old enough to have undergone revised regimens post-1965.

It’s to be hoped that more thoughtful examinations of the effects of the counterculture on those now aging Catholics who have grown apart from the Church in the experimentation and innovation may guide those who, having been raised in the pontificate of John Paul and his successors, seek solace — not only aesthetic comfort, but, as Valli, Porfiri, and Waters concur, a way to survive amid discontent and doubt. This demographic has been overshadowed, but it too deserves inclusion among the saving remnant. They had no recourse to clandestine TLMs or conscientious objectors in the 1970s or 1980s.

Once recovered, after inner struggles against doubt and external battles against detractors, a reverence for the sacred, reduced among millions of cradle Catholics, lingers on. Here again, Waters stands firm.

Headlines this past month in the Irish press reveal John Waters’s protests against a new shape-shifting foe. He and pro-life campaigner Gemma O’Doherty (another target of attack by the chattering classes) rally against COVID-19-related restrictions on public movement, in some circumstances only within a radius of two kilometers of home. Waters and O’Doherty sustain a long tradition of dissent against whatever draconian dictates they judge come down from powers that be. Given both figures’ increasing outreach to audiences deemed beyond the pale of acceptable neo-liberal or state-socialist opinion, what transpires from their appeals to the marginalized and discontented in the Catholic circles mapped as “here lie monsters” no-go territories will be worth watching as we continue into what the car commercials were the first to name “uncertain times,” as we ponder marks of beasts lurking ahead.