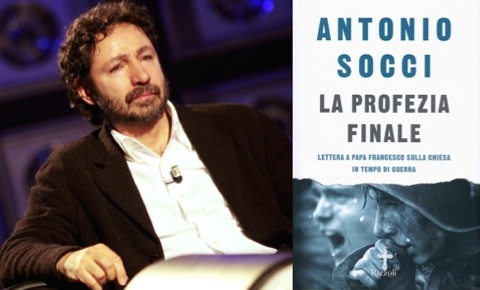

Antonio Socci — Italian Catholic, journalist, intellectual, and author — has become an increasingly significant figure through his analysis of the present ecclesiastical climate. If you’re unfamiliar with the name, here’s his brief Wikipedia bio:

Born into a working-class family, Socci joined the Communion and Liberation lay ecclesial movement in 1977. He studied at the University of Siena under literary critic Franco Fortini, earning a bachelor’s degree in Modern Literature. He worked for the weekly paper Il Sabato before becoming director of the office of Culture for the Province of Siena. In 1987 he returned to journalism.

For a few months Socci was the editor of 30 Giorni, before returning to the well known Il Sabato and after that closed in 1993, he moved to Il Giornale. He has also collaborated with other Italian media outlets, including Il Foglio, Libero and Panorama. In 2002 Socci joined RAI as the assistant manager of Rai Due. Between 2002 and 2004 he was the writer and presenter of a program called Excalibur. Since 2004 he has been hired as director, on behalf of RAI, at the advanced School of radiotelevision (RAI) journalism of Perugia. Meanwhile, he has become a best selling Catholic author in Europe.

Socci has, as you can see, been around for a while. And while as a Vatican watcher he isn’t the household name in the English-speaking world that Sandro Magister is, he has risen to prominence in large part because of his open questioning (in his book, Non é Francesco) of the canonical validity of the election of Pope Francis – a theory for which Socci has taken a great deal of abuse (he says in one interview that he was accused of being “possessed”) and from which he has since distanced himself.

But where Socci has really distinguished himself is in his incisive, documented, and cogent criticism of the Franciscan papacy itself. Criticism, it must be noted, that has won him the thanks of no less a figure than Pope Francis himself, who had begun reading it when he decided to send Socci a letter, saying that he believed “it will bring good things. In reality, critics help us also, to walk in the right way of the Lord”:

Shortly after publication of La Profezia Finale, Socci received a handwritten letter from none other than Francis himself. Addressed to “dear brother,” the letter was not unlike the telephone call Francis made to Mario Palmaro, late co-author of another searing critique of the pontificate bluntly entitled “We Do Not Like This Pope.” The gist of the letter and the phone call alike was the same: I appreciate your criticism of me.

One can be forgiven for thinking that so clever an ecclesial politician as Francis might have in mind a bit of buttering up of his most effective and widely read critics. But the letter to Socci (as well as the phone call to Palmaro) puts to rest any suggestion that “traditionalists” offend the Faith when they publish strong criticism of this Pope. Francis himself explodes that contention.

The above quote is buried at the bottom of an incredibly thorough review of the mentioned text — La Profezia Finale — Socci’s latest book. The review, penned by Christopher Ferrara and featuring his own translations from Italian, serves as a top-level summary of this “open letter” from a Catholic Italian journalist to his pope for those of us who may never see this important text in English. I do wonder if perhaps Mr. Ferrara did himself a disservice by placing the fact of Francis’ thanks to Socci at the end of his piece, rather than the beginning. After all, if it’s good enough for Francis, it should serve as an endorsement for his advocates, who would all be well-served by reading the rest of Ferrara’s review.

At just a hair under 6,000 words, it isn’t a quick read, but in my view it’s an absolutely essential one. I won’t attempt to summarize it further here, because I would risk diluting the larger narrative too much. I will for the moment content myself two quotes, the first taken from the passage I used in the title of this post:

Under the heading “Confusion” Socci remarks the unprecedented nature of the “Jubilee of Mercy,” the first Jubilee in Church history that “does not involve the memory of the earthly life of Jesus…. [and] celebrates only an ecclesial event: the fifty years since the Second Vatican Council (p. 108).”

Mercy, Socci writes, “was not invented in 2013,” but this event—with its thousands of “mercy doors” and no clear requirements for obtaining a plenary indulgence, seems to suggest (quoting Sandro Magister) “the total cancellation of sin, no longer with any hint of the remission of the consequent penalty. The word ‘penalty’ is another of the words that have vanished (p. 113).” Even the call for repentance and conversion is “set aside because you—as you have said publicly—do not wish to convert anyone and consider proselytism to be nonsense.”

Socci cites Francis’s homily of December 8, 2015 wherein he declares how wrong it is affirm of God “that sinners are punished by His judgment, without preferring instead that they are pardoned by His mercy.” The impression is that God “has pardoned everything ‘a priori’ and that it is not even necessary to amend one’s life.” Socci notes that Our Lord Himself lamented this “terrible self-deception” in an interior locution recorded by Saint Bridget of Sweden, wherein He tells her that the Church’s foundation in the Faith has been undermined “because everyone believes in me and preaches mercy, but no one preaches and believes that I am the just judge… I will not leave unpunished the least sin, nor without a reward the least good.”

Socci asks: “But why has your pontificate taken this turn?” The rest of the open letter presents the evidence for what he believes to be the answer to that question, and the answer could not be more explosive:

“… [I]nstead of combatting errors (and certain of the erring) you have set yourself to combatting the Church…. I would remind you that the Church is the bride of Christ for which He was crucified, and the servant who has received from the King the task of defending pro tempore His bride cannot humiliate her in the public square, treating her like a naughty child…. It is necessary to kneel before the Lord, not the newspapers” (pp. 119-120).

The second quote concerns the Holy Father’s relationship to the Eucharist, and his various interfaith gestures as relates to it. In this matter, Socci holds nothing back:

After noting that Francis evinces no concern over the internal enemies of the Church who, as Saint Pius X warned, work to undermine the foundations of the faith, Socci next discusses how, on the contrary, Francis seems to have little regard for the doctrinal differences between Catholicism and the various forms of Protestantism.

Under the heading “In the House of Luther,” Socci recalls Francis’s scandalous appearance at a Lutheran church in Rome to participate in a Sunday service during which he rambled on for some ten minutes in answer to a woman’s question about why a Lutheran cannot receive Holy Communion. In the process he characterized the Catholic dogma on transubstantiation as a mere “interpretation” differing from the Lutheran view, ultimately rather coyly suggesting that the woman to “talk to the Lord” about whether she should receive Communion from a Catholic priest—an act of sacrilege. “I dare not say more,” said Francis, having already said quite enough.

Noting Luther’s venomous hatred of the Mass, Socci asks Francis: “how is it possible not to be disturbed? (p. 193).” Dialogue with Lutherans, he writes, must involve “reciprocal clarity, not tossing into the thorn bush the heart of the Catholic faith (p. 194).” Here Socci quotes what may be the single most outrageous remark Francis has ever made. Said Francis to the Lutherans on that occasion:

“The final choice will be definitive. And what will be the questions that the Lord will ask us that day: ‘Did you go to Mass? Did you have a good catechesis?’ No, the questions will be on the poor, because poverty is at the center of the Gospel.”

Socci reminds Francis of what any well-formed child would understand: the infinite value of the Eucharist, Eucharistic adoration, and its worthy reception as compared to even a mountain of good works for the poor:

“But instead you, Father Bergoglio, seem to affirm that what counts are humanitarian merits that we acquire ourselves with our activism, with our ‘service’ to the poor.”

“This would seem to be a Pelagian idea. But—I repeat—the most amazing thing is that you contrapose [yet another false antitheses] “serving the poor” to the Mass, which almost reduces it to something superfluous (along with catechesis)” (p. 197).

Quoting the famous saying of Padre Pio that “It would be better for the world to be without the sun than without Holy Mass,” Socci confronts Francis with the implications of his own words and deeds over the past three years, including his curious refusal to kneel before the Blessed Sacrament:

“Permit me to confide to you, Father Bergoglio, that—from the entirety of your words and gestures—one gets the impression that you have some problem with the Holy Eucharist, and that you do not really comprehend its value and its reality.

“There are so many facts and actions that raise this doubt. The most evident… is your decision not to kneel before the Sacrament during the Consecration at Mass, nor in front of the tabernacle, nor during Eucharistic adoration (moreover you do not participate in the Corpus Christi procession in which your predecessors, kneeling, always participated) (p. 200).

And yet, Socci notes, Francis had no problem kneeling when, as Archbishop of Buenos Aires, he knelt to receive “the laying on of hands at the convention of Pentecostals in the Luna Park Stadium… Suffice it to say that your intermittent pain in the knees, which seems to arise only when before the Most Blessed Sacrament, beyond seeming rather bizarre, would not appear to be an acceptable explanation (p. 201).”

Suffice to say, Socci’s open letter covers a broad and vital range of topics, from the Jubilee of Mercy to the Synod to the absurdities of a Vicar of Christ more overtly concerned with ecological issues than the salvation of souls to Francis’ apparent contempt for orthodox Catholics…and so much more. This is perhaps the most incisive, substantive, and well-argued analysis I have yet seen on this issue. The conclusion is nothing less than that the present pontificate is deeply, disturbingly incongruous with other papacies before it — and even with Catholicism itself.

Please, if you share my concerns about Francis, however quietly, do yourself a favor and read this important piece of work. I found that in a number of points, Socci gives voice to arguments nearly identical to those we have made here over the past 19 months. If nothing else, this serves as confirmation that we are very much not alone in what we are seeing, and how we are seeing it.

I sincerely hope the full text is translated into English soon.