The following is a lecture given by artist Daniel Mitsui on 14 September 2015, to open an exhibit of his artwork at Franciscan University of Steubenville.

INVENTION and EXALTATION

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I wish you a very happy feast. This is a special day dedicated to the Holy Cross, one of two in Catholic tradition. The names of these feasts provide the name of this exhibit, Invention and Exaltation. The Invention of the Holy Cross, which is celebrated on May third, commemorates events that occurred in the year 326.

St. Helen, the mother of the emperor Constantine, travelled to Jerusalem to seek the True Cross. One of the Jewish scholars of the city knew its location; this was a secret that had been passed down through his family since the time of the Passion. He revealed it to Helen after interrogation; there, three crosses were found. To distinguish the cross of Jesus Christ from the crosses of the two thieves, each was held over a corpse. The deceased came to life upon contact with the True Cross. This Helen divided into three parts. One she sent to Rome and one to Constantinople. The third remained in Jerusalem. The man who revealed the location professed his faith; he later became a bishop and martyr, known as St. Quiriacus.

The relics of Our Lord’s Passion occupy a place within Catholic tradition close to that of holy images. Comparable veneration is given to each, and their histories are tightly interwoven. The Invention of the Holy Cross inaugurated the first great era of Christian art; Christian art emerged from underground along with the sacred wood. As described by the art historian Emile Mâle:

The discovery of the Holy Sepulcher and the True Cross in 326 must be considered as one of the great events in the history of Christianity; it was seen as a genuine miracle. Constantine immediately had magnificent monuments built on the site of rediscovered Calvary…. On the exact spot where the cross had been planted – the sacred spot regarded as the center of the world – a great cross was erected, encased in gold and decorated with precious stones…. Countless pilgrims from the remotest parts of the world flocked to Jerusalem. It was not enough for them to venerate the Holy Sepulcher; they visited all of the places consecrated by the Gospels, and everywhere they found magnificent basilicas…. All of these buildings were decorated with mosaics.

Sacred art here is confident, dogmatic and grand; its figures no longer wear the disguises of Classical antiquity, as they did in the art of the catacombs. Pilgrims to Jerusalem collected holy oil from the shrines in tiny flasks of cast metal or painted glass and wore them around their necks. These were decorated with the same images seen in the mosaics. Wooden stamps for pressing the images into the dough for eulogia bread were also popular. Through portable objects such as these, the artistic traditions reached the ends of civilization.

*****

In the early seventh century, the army of the Persian king Chosroës took Jerusalem and carried away the relic of the True Cross. According to the Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine:

Chosroës wanted to be worshipped as God. He built a gold and silver tower studded with jewels, and placed within it images of the sun, the moon and the stars. Bringing water to the top of the tower through hidden pipes, he poured down water as God pours rain, and in an underground cave he had horses pulling chariots around in a circle to shake the tower and produce a noise like thunder…. He sat on a throne in the shrine as the Father, put the wood of the cross on his right in place of the Son, and a cock on his left in place of the Holy Spirit.

The emperor Heraclius led a crusade to recover the relic of the True Cross; victory having been achieved, he personally restored the relic to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Today’s feast, the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, commemorates these events.

I have a special devotion to both of these feasts. How beautiful that the Catholic Church celebrates the finding of things that have been lost, and the reclaiming of things that have been stolen. This seems especially relevant in our own age; at times I feel that much of my religion has been lost, or stolen from me.

*****

The Apostle Paul commands all Christians to stand fast, and hold to the traditions they have learned. But where is a religious artist to stand when he has learned, in one sense, nothing at all? There is not now any tradition of sacred art that is handed down with a simple and ingenuous faith. There is not now any common mind and spirit among the faithful that might move them to build together, over centuries, a great cathedral. It is difficult enough to gather two or three who agree.

In a medieval monastic scriptorium or lay painters’ guild, no artist needed to question what he was taught, or to defend it. In our time, tradition is not a thing that is handed down so much as a thing that must be excavated. And once an artist begins to dig, he finds, in a different sense, altogether too much.

The part of the Catholic Church’s artistic heritage that has survived the centuries, the rust and moth that consume, the ravages of iconoclasts and revolutionaries, has been studied, documented, photographed and, in the form of digital images, made accessible as never before. Art museums, rare book libraries and cathedral treasuries the world over now display their collections online.

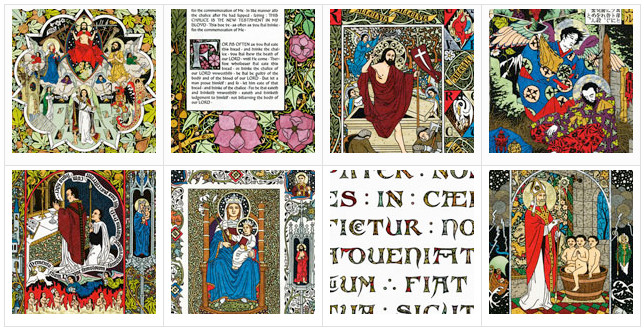

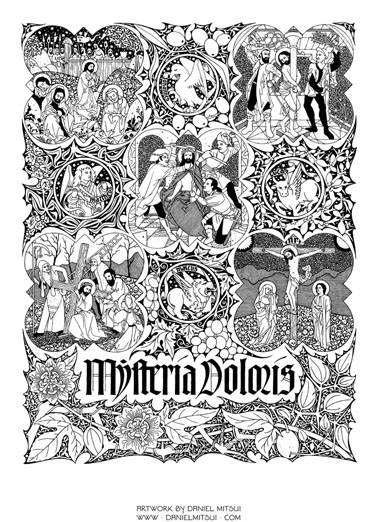

This is a boon to education and research; I rarely begin a drawing without first examining dozens of manuscript miniatures displayed in the Digital Scriptorium and panel paintings displayed in the Wikimedia Commons. This drawing of the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary borrows elements from paintings by Hans Holbein the Elder, Jan Polack, Hieronymus Bosch, Gerard David, Martin Schongauer, Rogier van der Weyden and Nikolaus Obilman; two decades ago, I would have found maybe half of these paintings reproduced in the art books available to me. Two centuries ago, I would have needed to cross an ocean to see a single one of them.

But in this superabundance of information, another problem emerges: the holy images are not lost, but reduced to triviality. Just about anyone in the world can download a high-quality digital photograph of the Chi-Rho page from the Lindisfarne Gospels, or the Incarnation Window at Chartres, or the Ghent Altarpiece. He can print it to hang on his wall; or he can print it on a t-shirt, a coffee mug or the case of his smart phone. He can put in on Pinterest or Instagram or crop it to use as a title banner on his web log.

The image thus becomes his means of constructing and projecting a persona, his means of saying: I am this sort of individual, this sort of Catholic, because I like this sort of art. What does selecting Fra Angelico say about him? Or Caravaggio? Or William Bouguereau? Does putting one painting by each in his screensaver prove his broadness of mind? Does adding one by Georges Rouault prove his boldness?

At that point, religious art ceases to be about God and His angels and His saints. It is not even about the artist who made it; it is about the person who chooses to like it. It is like a relic of the Holy Cross placed on a table to the right of a king’s throne: not destroyed, not forgotten, but not exalted either. It is set beside, rather than above, him.

*****

In our time, invention and exaltation describe well the duties of a religious artist. Invention here has the older definition of the word; it does not mean creating from nothing, but rather finding. If the artistic traditions have been buried, my task is to discover them; if they have been stolen, my task is to reclaim them. Once they are found or reclaimed, my task is to bring them to their proper place and give them honor as high as my abilities make possible; that is, to exalt them. This is like carrying the stolen relics back to Jerusalem, as Heraclius once did.

About this, the Golden Legend says:

Heraclius rode down the Mount of Olives, mounted on his royal palfrey and arrayed in imperial regalia, intending to enter the city by the gate through which Christ had passed on His way to Crucifixion. But suddenly the stones of the gateway fell down and locked together, forming an unbroken wall. To the amazement of everyone, an angel of the Lord, carrying a cross in his hands, appeared above the wall and said: When the King of heaven passed through this gate to suffer death, there was no royal pomp; he rode a lowly ass, to leave an example of humility to his worshippers…. With those words the angel vanished. The emperor shed tears, took off his boots and stripped down to his shirt, received the cross of the Lord into his hands, and humbly carried it toward the gate. The hardness of the stones felt the force of a command from heaven, and the gateway raised itself from the ground and opened wide to allow passage to those entering.

Here is a lesson for those who seek, as I do, to reintroduce the traditions; no project, even a righteous one, will meet divine favor unless it is undertaken with humility. It is not the artist that is to be arrayed, celebrated and exalted. God would rather brick him out of the Holy City than admit him to the ruin of his soul.

I often quote one of the fathers of the Second Council of Nicea, which was convoked in the year 787 to end the first iconoclast crisis. He said: The execution alone belongs to the painter; the selection and arrangement of subject belong to the Fathers. I consider the the selection and arrangement of subject that belong to the Fathers to be something like a relic, and the execution that belongs to the painter to be something like the making of a reliquary. Artistry without tradition is like an empty reliquary; beautiful perhaps, but unworthy of veneration. Tradition without artistry is like a relic kept in a cardboard box; worthy of veneration, but deserving of better treatment.

I believe that the traditions of sacred art deserve exaltation for the very same reason the relics of Our Lord’s Passion deserve it – because they touched God.

*****

Few ever have understood the power of touching God so well as that woman afflicted for twelve years by an issue of blood, who but touched the hem of His garment and was made whole. This woman, traditionally called St. Veronica, is an important figure in the history of sacred art. Early ecclesiastical historians attest that she erected a statue in her home city of Paneas commemorating the miraculous cure. Eusebius of Cesarea recounted:

There stood on a lofty stone at the gates of her house a bronze figure of a woman, bending on her knee and stretching forth her hands like a suppliant, while opposite to this there was another of the same material, an upright figure of a man, clothed in comely fashion in a double cloak and stretching out his hand to the woman…. This statue, they said, bore the likeness of the Lord Jesus. And it was in existence even to our day, so that we saw it with our own eyes when we stayed in the city.

The statue was mutilated during the reign of Julian the Apostate; the whereabouts of its remains are unknown.

Veronica means true image. The name is shared with another woman who touched God. This St. Veronica pressed a cloth to the face of Christ as he walked to Calvary; a true image was left upon it. I am amused to know that, even though monumental sculpture fell out of practice in the Catholic Church until the early Gothic era, and even though printmaking did not flourish as a sacred art until the late Middle Ages, both forms of art were present at the very beginning of Christianity.

As was painting; numerous works are attributed to the Evangelist Luke, including ones still venerated in Rome, Smolensk and Czestochowa. Now skepticism about some of these attributions is justified; analysis of materials does not always indicate a first-century origin. However, it certainly is plausible that holy images venerated today are copies of a Lucan original, or copies of copies. The conviction of the faithful in patristic and medieval times was that Christian art is as old as the Church. This conviction does not depend on any specific painting’s authenticity.

*****

I sometimes say that I am a Spirit of Nicea II Catholic. That is a joke, its point being that I keep that ecumenical council at the forefront of my mind, living as I do in a time similar to the iconoclastic crises. I do not seek to interpret its doctrine regarding art and tradition beyond what its words actually say; indeed, what they actually say is bold enough. Its dogmatic decree, among other things, states:

Those, therefore who dare to think or teach otherwise, or as wicked heretics to spurn the traditions of the Church and to invent some novelty, or else to reject some of those things which the Church has received (the Book of the Gospels, or the image of the cross, or the pictorial icons, or the holy relics of a martyr), or evilly and sharply to devise anything subversive of the lawful traditions of the Catholic Church … if they be bishops or clerics, we command that they be deposed; if religious or laics, that they be cut off from communion.

I do not think that anyone can honestly interpret those words that refer to the image of the cross, or the pictorial icons, or the holy relics of a martyr in an abstract sense. They refer to cults of devotion, to traditions that exist in fact. These may not be inerrant or infallible, but they nonetheless have a permanent content that endures through the centuries. They cannot be insulted, discarded or remade entirely without ruinous effect.

*****

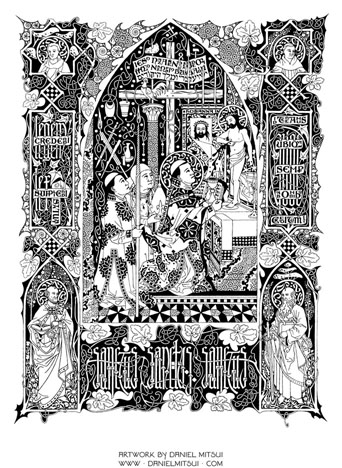

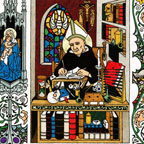

This is a recent drawing of mine; I have not yet issued a relief print of it, so it is not on display in the gallery. Its central image depicts a miraculous vision of Christ surrounded by the instruments of His Passion that St. Gregory the Great saw while celebrating Mass. More broadly, the drawing is about Christian knowledge: how and whence it is received.

St. Gregory was the Bishop of Rome, and thus the inheritor of the authority of Saints Peter and Paul (whom I drew in the bottom corners). He is one of the four great Latin Church Fathers. He was the codifier of the Roman Mass and its music (which is why I wrote the words Sanctus Sanctus Sanctus in the bas-de-page, together with the chant neumes from the Missa Kyrie Fons Bonitatis). Shown here, St. Gregory is the recipient of a mystical vision, one of those divine reminders of a holy truth: in this event, the selfsameness of the Man of Sorrows and the Sacrament of the Altar.

But this drawing is not meant to suggest that Christian knowledge is altogether dependent on personalities so great as St. Gregory; so great a pope, theologian, liturgist and mystic may never again walk the earth until the resurrection of the flesh. Nor is to meant to suggest that Christian knowledge is altogether dependent on a privileged communication between Christ and His vicar on earth; events such as the Miraculous Mass of St. Gregory are worthy of artistic treatment precisely because they are extraordinary.

Fundamentally, the reason we know anything about Jesus Christ – that He was born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried, descended into hell, rose again on the third day and ascended into heaven – is because these things actually happened, and someone saw or heard them happen. Before they were written as scriptures, before they were declared as doctrines, they were kept as memories.

If the Blessed Virgin Mary had told nobody what the Archangel Gabriel had said to her at the Annunciation, we would not know it. If Jesus Christ had told nobody that His sweat became as blood while He prayed in Gethsemane, we would not know it. Even St. Luke, writing with divine inspiration, knew about these events according as they have delivered them unto us, who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word. Our tradition identifies witnesses even of the Descent into Hell: those saints that had slept, who rose from their tombs after the Resurrection of Christ, came into the holy city and appeared to many.

In the upper corners of the St. Gregory picture, I drew two theologians of the fifth century, St. Prosper of Aquitaine and St. Vincent of Lerins. During their earthly lives, these men were theological opponents, more so even that Saints Peter and Paul. I consider it a mark of providence that from their disputations, two beautifully complementary ideas emerged.

St. Prosper articulated the well-known maxim: The law of worship establishes the law of belief. Worship was the first way by which the memories of those who saw, heard and touched Jesus Christ were carried forward. Because the law of worship predates such things as the settlement of the canon of scripture or the definitions of the ecumenical councils, it is the first criterion of orthodoxy. Thus it is the first criterion of sacred art as well. Sacred liturgy and sacred art must be concordant, for they are records of the same memories.

St. Vincent wrote in his Commonitoria: We hold to what has been believed always, everywhere and by all. Universality, antiquity and consensus are the marks by which a true tradition can be told from a false. Now St. Vincent makes clear that this principle is not to be taken so literally that a single counterexample would suffice for disproof; all, or at least almost all, he says. Elsewhere in the same book, he describes the true development of tradition, which he compares it to the growth of a body:

Men when full grown have the same number of joints that they had when children; and if there be any to which maturer age has given birth these were already present in embryo, so that nothing new is produced in them when old which was not already latent in them when children. This, then, is undoubtedly the true and legitimate rule of progress, this the established and most beautiful order of growth, that mature age ever develops in the man those parts and forms which the wisdom of the Creator had already framed beforehand in the infant. Whereas, if the human form were changed into some shape belonging to another kind, or at any rate, if the number of its limbs were increased or diminished, the result would be that the whole body would become either a wreck or a monster, or at the least would be impaired and enfeebled.

Catholic tradition is based on real memories of real events. Something either is part of that tradition or it is not, just as something either is part of a body or is not. If it is part of that tradition, this is evident in the law of worship and the agreement of the Church Fathers; these are the epistemic bridges between the age of the eyewitnesses and our own.

As Catholics we have the benefit of the Magesterium exercised by the successors of the Apostles, our bishops. They have been given the authority to judge disputes over tradition and to bind the faithful to assent. But they do not create tradition themselves. They receive their knowledge from existing sources, and these are sources that anyone can seek and find.

By looking to liturgical and patristic sources, a religious artist can draw a more complete picture, he can dig deeper, than by looking to magisterial documents only. He may unearth something wonderful. Discovering a tradition that has been lost is thrilling; it is like knocking the dirt from a buried piece of lumber and finding that it can yet raise the dead.

*****

The selection and arrangement of subject in sacred art belong to the Fathers because they say the same things as the Fathers, in the same manner. Patristic language, whether written or painted, is more symbolic than literal.

The four winged creatures that surround Jesus Christ in so many holy images are those that appeared to the prophet Ezekiel and later to St. John. They are symbols of the four Evangelists. The man represents St. Matthew, whose book begins with a genealogy, a record of men. The ox is a sacrificial animal, and the Gospel of St. Luke opens with St. Zachary offering sacrifice at the Temple. The lion represents St. Mark, whose book begins with a voice crying, or roaring like a lion, in the wilderness. The eagle was believed to gaze directly into the sun, and the Gospel of St. John opens with insight into impossibly dazzling truths. In art, the man and the eagle are often given higher position, for the Evangelists they represent received their knowledge from direct witness rather than hearsay.

The apocalyptic beasts are polysemic; they represent also the life of Jesus Christ, respectively His Incarnation, His sacrificial death, His Resurrection (He couched as a lion; who shall rouse him up?) and His Ascension. Furthermore, they are symbols of Christian virtues: rationality, self-sacrifice, courage and contemplation.

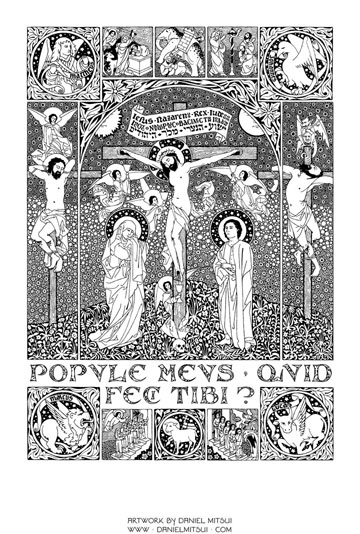

The Church Fathers saw everywhere in the Old Testament prefigurements of the New. I included the Sacrifice of Isaac as a marginal picture to this Crucifixion; the association of the two sacrifices is made again and again in liturgical texts and theological writings. The death of Eleazar Maccabee beneath a war elephant I drew also; as far as I can tell, this prefigurement was first noted in the Speculum Humanæ Salvationis, an book of typologies from the early fourteenth century. But the Speculum’s author did not alter the ancient tradition; rather, he progressed it according to the established and most beautiful order of growth. The symbol was latent in the event from its occurrence; the manner of thought that reveals it was taught by Jesus Christ Himself: As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of Man be lifted up.

The Crucifixion scene, as traditionally arranged, is itself full of symbolic meaning. Jesus Christ is the new Adam, whose death on the cross redeems the original sin. Just as Eve, the bride of the first Adam, came forth from his side while he slept, so the Church, the bride of Christ, came forth from his side while he slept in death on the cross; I here paraphrase St. Augustine. The blood and water that pour from the opening in the new Adam’s side represent the two most important sacraments: Eucharist and Baptism. The wound is almost invariably depicted on Christ’s right side, for it was from the right side that Adam’s rib was taken. To the right side of the Cross (from Christ’s perspective) appear the symbols of the new covenant: the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Good Thief and the sun. The moon, whose indirect light represents the old covenant, is to the left. This is a theological lesson, not a record of the day’s astronomical positions.

A similar lesson is taught in this image of the Resurrection. Before the thirteenth century, the Resurrection rarely appears in sacred art. The older practice was to depict the holy women visiting the tomb, for this is the story of the Gospel in the Mass of Easter Sunday. This composition might be denounced as a novelty did it not illustrate an ancient exegetical tradition. Its allegorical nature is revealed by a curious detail. Emile Mâle explains:

In contrast to the Gospel narrative which tells how, after the Resurrection, the stone was rolled away by an angel on the morning after the sabbath, Christ is almost invariably shown rising from a tomb from which the stone has already been removed. The old masters, ordinarily so scrupulous and so faithful to the letter, had a reason for thus uniting two distinct events. There is not the least doubt that they wished to recall the deep significance which was attached by the Fathers to the removal of the stone. The stone before the tomb was in fact a symbol. It is, says the Glossa Ordinaria, the table of stone on which was written the Ancient Law – it is the Ancient Law itself. As in the Old Testament the spirit was hidden beneath the letter, so Christ was hidden beneath the stone.

Those who indeed set out to alter the anatomy, to spurn the traditions of the Church and to invent some novelty, to forbid all of a sudden and to consider harmful what earlier generations held as sacred, were proud enough to leave a written record of their intentions. That is convenient for me, because I thus know exactly whose influence to stanch and reverse.

I allude here to the more extreme humanists, whose determination to recreate the culture of Classical antiquity led them to despise and replace the greatest art of the Middle Ages; also to the censors of the late sixteenth century who took the brief and unspecific words of the Council of Trent regarding art as instructions to subject the whole tradition to their critical judgment. The most influential of these, John Molanus, was blind to the symbolic order in medieval art; he condemned and forbade every traditional composition that he did not understand, which amounts to nearly all of them. In modern times, many artists have made violence to tradition the very premise of their art.

My task, as a religious artist working in the present day, is to heal those injuries done, to restore the impaired and enfeebled body to strength. It is a difficult and seemingly impossible task, but I know that the touch of God, the touch of His cross, the touch even of the hem of His garment, can make a body whole in an instant.

*****

St. Vincent’s metaphor of the body makes true progress a matter of integrity, rather than of slowness. During the greatest eras of Christian art, tradition grew and developed with astonishing rapidity. The thriving that followed the Invention of the Holy Cross might be considered the toddlerhood of Christian art; the era of the early Gothic might be considered its adolescence.

Here again, relics of Our Lord’s Passion were the catalyst. Annual fairs held in honor of relics housed at the Abbey of St. Denis, near Paris, were so popular by 1137 that Suger, the abbot, noted:

The crowded multitude offered so much resistance to those who strove to flock in to worship and kiss the holy relics, the Nail and Crown of the Lord, that no one among the countless thousands of people because of their very density could move a foot; that no one, because of their very congestion, could do anything but stand like a marble statue, stay benumbed or, as a last resort, scream…. Moreover the brethren who were showing the tokens of the Passion of Our Lord to the visitors had to yield to their anger and rioting and many a time, having no place to turn, escaped with the relics through the windows.

Abbot Suger resolved to enlarge and to rebuild substantially the abbey church; his artistic and architectural project proved epochal. Here, cross-ribbed vaults, pointed arches and flying buttresses were first combined in a new kind of architecture, the framework upon which the arts of monumental sculpture and stained glass climbed and flourished. In the windows of the abbey church, the theology of light expounded by the author of the Celestial Hierarchy, called Dionysius, was given sensible form.

Bernard of Clairvaux’s argument against artistic splendor was spectacularly refuted in works such as the great crucifix of St. Denis. This stood more than thirty feet tall in the new abbey church; its pedestal was adorned with figures of the four Evangelists, its pillar with enamel panels illustrating events in the life of Jesus Christ and their prefigurements in the Old Testament, its cross with gemstone cabochons and large pearls, and a corpus worked in gold.

The art here begun inspired the great cathedrals of Sens, Chartres, Laon, Paris, Bourges, Rheims and Amiens. It spread beyond France, throughout Catholic Europe. In its comprehension and exactness it is analogous to scholastic theology. A Gothic cathedral is a Summa Iconographica, a codification and perfection of ancient tradition.

*****

In the thirteenth century appeared its finest specimens of architecture, sculpture and stained glass. Because I specialize in small, two-dimensional works of art, I more often look to the following two centuries, in which the arts of manuscript illumination, panel painting, tapestry and printmaking culminated. It is in these later expressions of Gothic that I most often seek inspiration.

I consider myself a revivalist, but I do not think of Gothic as a mere historical style; that would make of it a very boring thing indeed. A farsighted and generous consideration of beautiful forms is in the true spirit of this art. Its artists may have deferred to the Fathers in the selection and arrangement of subject, but in the execution that belonged to them, in the exaltation of subject, they withheld not their treasures but offered whatever was most excellent.

The Flemish painters hung Oriental damasks behind their Virgins, and laid Oriental carpets beneath their feet. The Italians copied ornament from art that arrived by trade from Mamluk Egypt. Their saints wear garments bordered with Kufic letters (spelling gibberish) and radiate haloes that resemble platters made by Egyptian goldsmiths.

In my own drawing of the Mass of St. Gregory, I similarly styled the haloes. The vestments worn by the pope and his deacon display textile patterns more Asian than European. The pillars and altar contain Petoskey Stone, a fossil coral native to North America.

I consider it a sad mischance that the spirit of Gothic art was expelled from Catholic Europe just as the Age of Exploration began. A few treasures of the Aztecs crossed the Atlantic Ocean in time to be admired by Albrecht Dürer, an artist who stood astride the end of the Middle Ages. Most of the treasures arrived too late. Medieval artists never saw the art of the Mughals or of the Mings. Just imagine what they would have done, had they seen it!

*****

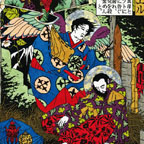

I imagine this myself; literally, I make images of it, both by importing foreign art into the traditional compositions and by exporting the traditional compositions into foreign art. The style of Japanese woodblock prints has proven especially popular among my patrons, but my interest is not confined to it; Chinese painting, Indian and Persian manuscript illumination also have my curiosity. The affinity between Gothic art and the art of these other cultures was noted by the scholar Martin Lings:

The reason why medieval art can bear comparison with Oriental art as no other Western art can is undoubtedly because the medieval outlook, like that of the Oriental civilizations, was intellectual. It considered this world above all as the shadow or symbol of the next, man as the shadow or symbol of God…. A medieval portrait is above all a portrait of the Spirit shining from behind a human veil. In other words, it is as a window opening from the earthly on to the heavenly, and while being enshrined in its own age and civilization as eminently typical of a particular period and place, it has the same time, in virtue of this opening, something that is neither of the East nor of the West, nor of any one age more than another.

I do not consider my artwork an exercise in reënactment. When I draw, I pretend no ignorance of those real facts unknown to artists of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries: the existence of Japan, for example, or of microörganisms, or of platypodes). I accept the principles of medieval art not because they are medieval, but because they are true – true in any time, any place, any culture.

I believe that the art called Gothic answers the challenges of invention and exaltation like no other. I draw my own art from it, and find it an inexhaustible source, like the life-giving cross.

*****

In the fourth century, St. Paulinus of Nola recorded that the portion of the True Cross kept in Jerusalem had a miraculous property; no matter how many pieces were broken from it, its size did not diminish. St. Cyril of Jerusalem compared it to the loaves and fishes that fed multitudes and left over basketfuls. John Calvin famously scoffed that if all the pieces of wood venerated as fragments of the True Cross were collected together, they would make a big shipload. There are studies refuting this claim, but if the old Catholic tradition is to be believed, it might be correct! I doubt that the explanation would satisfy Calvin, a man determined to see fraud; but even he must admit on Biblical evidence that we live in a world in which these sort of things happen.

In another way, relics are inexhaustible even when the Law of Conservation is not miraculously suspended. Catholic tradition maintains that their virtue can imparted through contact. Things that touch the relics of Our Lord’s Passion or the mortal remains of the saints become relics themselves, although of a lower class. When I speak of the virtue of a relic, I do not mean a magical property that works independently of the will of God (for the working of miracles is proper to God alone), but rather the quality that sets it apart from an ordinary piece of wood or bone or cloth. That distinction is real enough to terrify demons.

In the Middle Ages, the faithful believed that this virtue could also be transferred optically; where the relics were inaccessible to touch, pilgrims held up mirrors to reflect them; the mirrors were then carried homeward, and treated as relics of a lower class.

*****

The Cathedral of Aachen is home to four relics of particular distinction: the dress worn by the Blessed Virgin Mary on the night of the Nativity, the Holy Infant’s swaddling cloths, the fabric used to wrap the head of St. John the Baptist and the loincloth worn by Jesus Christ on the cross. Since the fourteenth century, these have been displayed at septennial jubilees, unfurled from the gallery connecting the cathedral’s belfry to its octagonal dome.

In anticipation of the jubilee of 1439, a clever silversmith began to manufacture quantities of pilgrim mirrors, convex ones that could reflect a panorama. He had partners in this enterprise; all were disappointed when the jubilee was postponed due to plague. At a loss for money, the silversmith offered to share with two of his partners another idea, one that he had been developing in secret. They listened, doubled their investments, and set to work on the confidential endeavor. The silversmith’s name was Johannes Gutenberg; the endeavor involved the making of tiny metal letters that could be arranged into text; a viscous oil-based ink; and a press like that used by vintners and bookbinders, but adapted to the purpose of printing on paper, an art that previously had been done through manual pressure.

Indirectly, the cult of relics gave Gutenberg his funding. I think that it gave him also the idea for the printing press itself. Consider the mechanism of a printing press: a matrix – which might be a wooden block with a holy picture carved in its surface, or a Biblical text set in forty-two lines of metal type – is inked, and touched to a different object, a piece of paper. Through touch, the matrix makes the paper into something like itself. The process can be repeated with practically no exhaustion of the matrix. Every printer knows that typeset text must run backwards; when printed, images are reversed, just like things reflected in a mirror.

Gutenberg believed that relics can impart their virtue through contact and reflection. In the years when he conceived his printing press, this was at the forefront of his mind, as was the problem of sharing this virtue among great multitudes; we know this as a fact of history. What Gutenberg invented was a technological metaphor for pilgrimage.

In fact, many printed sheets of the fifteenth century were distributed as pilgrim souvenirs; they served the same purpose as holy oil flasks and convex mirrors. Later scholars gave to the printed books of that century the name incunabula; how fitting this is! Incunabula is the Latin word for swaddling cloths, and the Holy Infant’s swaddling cloths were among the relics exhibited at the Aachen jubilee.

*****

I am determined to make printed works of art in the same spirit, ones that look, feel, smell and are like those of the fifteenth century. In the coming years, I hope to publish my own illustrated editions of two popular late medieval religious blockbooks, and then a Book of Hours. To date, I have issued relief prints only in individual sheets, their images based on my original drawings and typefaces. My method is not exactly Gutenberg’s; I hire pressmen who operate machines much faster than his, and they transfer the images and text onto plates by a photochemical process. But the printed sheets are nonetheless made by the same essential mechanism of contact and reflection.

Fourteen of these are on display in the gallery here. These were printed in black ink only; I added the color, the gold and palladium leaf to them by hand. I hope that you will enjoy looking at them. Thank you.

|

|

|

|

|

|

*****

The color images are the hand-colored relief prints included in the exhibit. Descriptions of these can be read at the following web pages:

Last Judgment

And Rising / For I Received

Resurrection

Second Dream of St. Joseph

Mass for the Dead

Our Lady of Walsingham

Pater Noster

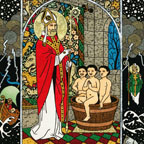

St. Nicholas of Myra

Ecce Quam Bonum

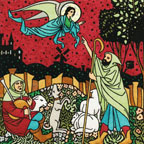

Annunciation to the Shepherds

St. Brendan the Navigator

Ss. Thomas Aquinas and Anselm of Canterbury

St. Cecilia

St. Albert

*****

Works quoted:

Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend, translated by William Granger Ryan, (Princeton University Press, 1993).

Emile Mâle, Religious Art in France: The Twelfth Century, translated by Marthiel Matthews, (Princeton University Press, 1978).

Emile Mâle, The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century, translated by Dora Nussey, (New York: Icon Editions, 1972).

Eusebius, The Ecclesiatical History, translated by J.E.L. Oulton, (Harvard University Press, 1932).

Second Council of Nicea, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Volume XIV, translated by Henry Percival, (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing, 1900).

St. Vincent of Lerins, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Volume XI, translated by C. A. Heurtley, (New York: Cosimo, 2007).

Suger of St. Denis, On the Abbey Church of St. Denis and its Art Treasures, translated by Erwin Panofsky, (Princeton University Press, 1979).

Martin Lings, The Sacred Art of Shakespeare, (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International, 1998).