The prospect of using aborted fetal tissue in the massively funded project to develop a COVID-19 vaccine — a particularly gruesome sign of the techno-barbarism of our age — makes when human life begins (and with it, human personhood), and how much we can know about it for sure, once again a pressing scientific and philosophical question. The Church’s teaching is clear: we must treat every fertilized ovum as a human being and never deliberately cause harm to him. Our “marching orders” are clear. But what is the history of this position, and what is its epistemological status?

Following the lead of Aristotle, St. Thomas Aquinas held that, ordinarily speaking [i], a human person did not exist from the moment of conception, but rather that the conceptum passed through stages of growth, first vegetative, then sensitive, finally becoming a rational animal when the immortal soul was infused into the body at the moment of “quickening.” He held this because he believed that the human body has to be sufficiently developed in its organs to allow the presence and operation of a rational soul. This was not too surprising a view, given the extreme simplicity of ancient and medieval observational science.

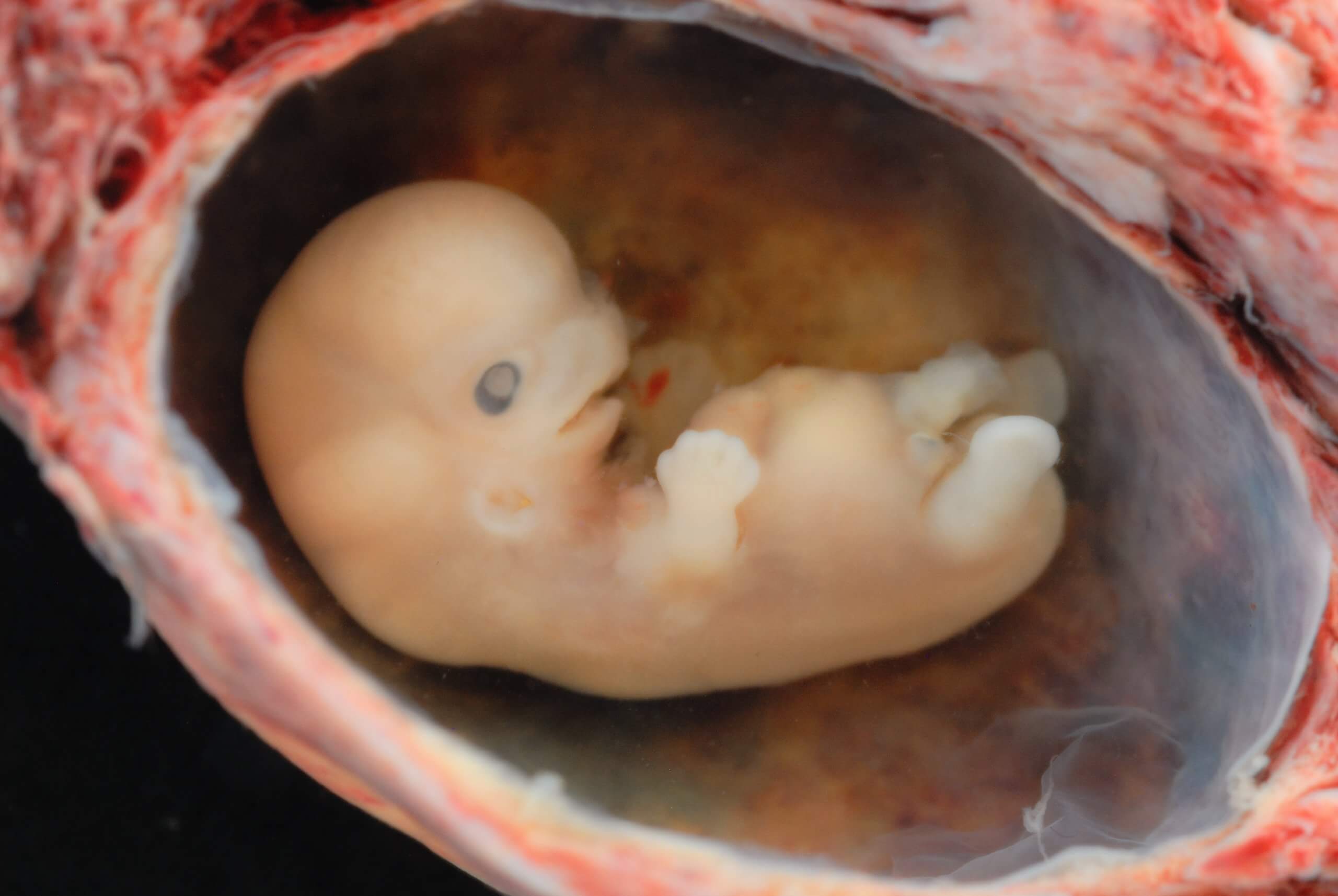

Needless to say, it is no longer possible to take seriously the biological component of St. Thomas’s view of the beginnings of generation. Already in early modern times, the English physicist William Harvey (1578–1657) was able to observe the intricate formation of body parts at the earliest stages of gestation, and he hypothesized that the whole animal was present from the moment of conception, though in potency. Harvey applied Aristotle’s act-potency doctrine more consistently than even Aristotle had done.

Most Catholic ethicists of the past century have taken as the likeliest position that animation — that is, the imparting of the rational soul, the principle of human life — occurs at the moment of conception, since every moment after that seems to be only the unfolding of a pre-existent pattern, a making explicit of what is implicit. There is no obvious line between non-rational and rational. If one really meant to make actual reasoning the distinctive mark of the human, then we could not be defined as human until around the age of six. When it comes to the full unfolding of human identity, we are evidently dealing with something that remains “in potency” for a fairly long time. Here one might recall the poignant thesis of Jean Piaget (1896–1980) that a child completes his human development in the “social womb” of the family into which he is born.

As mentioned above, St. Thomas’s position derived from the idea that the nobler the “form,” the more highly developed the “matter” had to be before it could be informed by that form [ii]. There had to be appropriate matter for the form. Knowing what we know today about cells and DNA, we realize that even the simplest living things, like amoebae or a paramecia, have an almost unfathomable complexity of structure. Far more is this true of the human zygote. The matter is as ready as it will ever be to receive its form, the rational soul. If we take the soul to be an immaterial principle wholly present in each and every part, giving being to the body, we will not think the soul requires large-scale organs for its being; it requires them only for the operation of its powers. Put differently, what is required for the soul to be joined to prime matter is the primordial capacity for differentiated functionality, not a finished architecture of actual functioning. Such capacity is had in virtue of human DNA in its cellular habitation, since from this root source proceed all subsequent parts [iii].

In short, the principles of Aristotelian physics and the discoveries of modern biology taken together entail the extreme likelihood that human life is present from the first moment of conception — in other words, that the substantial form of the human person, the rational soul, is informing the matter provided by the sperm and egg, from the moment the gametes join together to furnish the substratum of the human body [iv].

It is for this reason that the Catholic Church, in her fundamental commitment to rational science, holds it to be most probable that ensoulment occurs at the moment of conception; for all intents and purposes, we must assume this to be so. The following probabilistic argument can be used to illustrate the claim. If you are a soldier and you see far off on the horizon a person with a gun, but you don’t know whether it’s a civilian, a fellow soldier, or an enemy, are you permitted to fire yet? No, you should wait, on the assumption that it might be someone you are not supposed to shoot at. You would have to be reasonably certain that it was an enemy before you were morally entitled to fire. In like manner, if there is even merely a good chance that an embryo is human, one is not morally permitted to commit violence against him.

This argument rests on the more universal premise that it is always wrong to kill an innocent human person. Defenders of abortion are forced either to argue that the embryo is an aggressor to the mother and therefore not innocent — a ridiculous position, albeit one that has been argued! — or that it is not wrong to kill innocent persons if a supposedly “greater good” is at stake, such as (in the minds of abortion proponents) “personal happiness” or “freedom.” One wonders what kind of happiness we are speaking of that demands the slaughter of another who impedes it; one wonders what kind of freedom can exist only by suppressing the freedom, or the existence, of others [v].

Would abortion still be evil if the fetus were not yet human?

The Church has never defined the precise moment of ensoulment — the moment when Almighty God infuses a spiritual soul into the matter of the human body. The Church has declared, however, that it is never permissible to kill offspring, at any stage of development, even if per hypothesis the embryo were not yet informed by the human soul.

St. Thomas’s argument against abortion at any stage, despite his belief that you did not have a man until some time after conception, is based on a permanently valid point of Aristotelian natural philosophy. The end of generation is the form or species, and so all the prior stages are leading up to, in fact ordered to, the coming-to-be of an individual of a certain species. If the form is not already present all the while, its advent is still being prepared for in the early weeks of gestation. The stages of fetal development are not random: they have an obvious and intelligible order precisely because of their ordination to the ultimate formation of a person. If, therefore, the embryo were per hypothesis not yet human, still it would be human-in-potency, human in its ontological status. It could not be the embryo of a horse or a dog or a starfish. And because of the dignity of the human form, the body that will be the human body shares in that dignity, as ordered to it. Even if the body is only a part of what man is, and not the nobler part (because it is not spiritual, incorruptible, immortal), still it has all the dignity of man because of its order to the soul and its immediate or eventual union with the soul [vi].

Let me give an example to illustrate. When a house is being built, we can see that it is going to be a house even when it’s not finished, because the plan pre-exists. The half-built barn is still a barn, though incomplete. That’s why if I burned it down, I’d be guilty of destroying a barn. It’s as if the half were the whole, as ordered to being the whole. Indeed, if I burned the architect’s plans for the barn, or the pile of boards sitting in the field, in either case I could be prosecuted for criminal activity; I would have done something wrong, even if I hadn’t burned down a completed barn.

Another example: When I am introduced to someone and shake his hand, I don’t think my hand is being introduced to his hand; rather I know that my person is being introduced to his person. The hand represents the person because of the essential link between part and whole. In just this way, if someone slaps me in the face, I consider it not an offense of a hand against a face, but an attack on my person by another person. In like manner, the body is part of the human composite. The body is what it is only because of its relationship to the soul — and this would be true even on St. Thomas’s outmoded account, when the body-in-formation is going to be only human and hence already shares in the dignity of its final goal. As such, an injury done to the body is an injury done to the human person.

Another example: if I intend to do something and get interrupted so that I cannot accomplish my intention, still the deed was as if done. If I was going to shoot someone and my gun didn’t fire, I could still be prosecuted. Here, one can see that the deed is already present, in a way, in the intention. We are dealing once more with the same basic relationship of potency with act [vii].

Why has the Church not yet defined the moment of ensoulment?

If the Church teaches definitively that abortion at any time is malum in se (intrinsically evil), why does she not specify, once and for all, the exact moment of animation?

If the resolution of this question pertains to the order of biological knowledge, it may not be within her competence to define it. Unless God had revealed to us the truth about this exact question, or unless a position can be seen to be metaphysically necessary, we would have no way of answering it except by our experimental knowledge and reasoning. Our experimental knowledge points to an answer, but it does not demonstrate it. Hence, we have to rest content with probable arguments at the scientific level. At the philosophical level, we can say something more: the embryo, if not human in esse (in being), would necessarily be human in fieri (in becoming). Aggression against him is therefore aggression against a human person, in act or in potency; either is a grave evil.

Two further things could be said about the Church’s stance. One is that she has come very near to defining conception as the moment of animation because of her frequent statements that we are required to protect human dignity “from conception to natural death.” Strictly speaking, it is only a person that enjoys the dignity of the divine image (imago Dei). Hence, it seems to me that some Church statements indirectly assert the actual humanity of the embryo at conception.

Another point is that the proper context for understanding, and hence debating, issues concerning the unborn child is the context of healthy sexuality and a holistic view of how union and procreation always go together. All the ethical nightmares we are dealing with result from the mental sickness of separating these two dimensions. In other words, establishing the exact moment of animation would be (to some extent) practically irrelevant, as the battle is not going to be won or lost at that level. Even if the whole world could be convinced that the unborn child is truly a person from the moment of conception, there would always be the Judith Jarvis Thompsons and Peter Singers who would argue about “the aggression of the child” and “the woman’s prior rights.” What must be recovered is a right attitude about the value of human life in itself and the natural ordering of sexual activity to the transmission of human life. Those who believe life to be worth living and who wish to share the good they have received would never think of abortion, or even any method of preventing life from coming to be.

I think it is not possible for us ever to understand fully the processes of life, and this is especially true of a process as complex as reproduction. All we know for sure is that when fertilization occurs, many profound transformations begin in cellular structure, and the parts of the embryonic body begin to emerge under what seems the guiding hand of the substantial form, the soul. St. Thomas seemed to think there was no inherent contradiction in asserting that the life force at work here was not yet the rational, personal soul, but a more primitive life force inherited from the father’s seed, which prepared the ground for the infusion of the rational soul some weeks into pregnancy. How would we know for sure that delayed animation is impossible? The fact that the embryo looks more and more human would not, in and of itself, prove the point. That is what I meant when I said above that our biological knowledge is inadequate for definition.

To be more specific: our knowledge must be inadequate, because the rational soul is an invisible principle whose advent or departure we cannot directly see, but can only judge from certain observable effects. As St. Thomas maintains, the proper object of the human intellect is the material singular. We do not have a direct knowledge even of our own souls; we have a direct knowledge of bodies, our own bodies, our acts performed in and through the body, and it is only by a laborious process of reasoning that we can climb back into the soul’s powers and gain some vague knowledge of the soul’s essence. All the more severely limited, then, is our knowledge of the soul of another: when exactly does it begin to exist?

Conception is by far the most likely moment, yet there is no certainty. It is somewhat like the certainty we have about death. We can know generally when the soul departs: all vital operations totally cease. When the vegetative functions cease and all signs of life are gone, there is no doubt that the soul is disunited from the body, or more precisely, the body has ceased to be able to receive the informing essence of the soul. In a sense, we are dealing with something much clearer when it comes to death: a living thing that is evidently a human person, whose death is nothing other than the separation of a rational soul from its correlative body. At the start of life, we see a complex bundle of cells ever dividing and articulating itself. We can conclude with certainty that this complex bundle of cells is alive. Where there is life, there is soul. But what kind of soul? Is it necessary that this soul be rational at the first moment? If God always applied Ockham’s razor to his works, so to speak, one could readily accept that there is but one soul at work from conception to death. But whatever belongs to the sphere of things freely chosen by God is unknown to us unless it is either revealed or deducible from per se nota principles. And there is no perfect answer on this matter from either source.

An objection to this line of argument

One might object that “what we see here” is not just a bundle of cells. We can see very well what is going on within those cells: the human genes will direct the embryo into the formation of a human body with all of its specific structures, including the brain, which seems to integrate the functioning of the organism and is the main organ made use of by the intellectual powers of the soul. This genetic information is material and yet human — specifically human matter, namely, the primordial plan of the body and all of its organs. This little “thing” cannot grow into a tree or a cat, and there is no phase in his development when he is a plant or some animal. He is always a man because he has all structures already present in a condensed form, even as one who has a Mozart opera on a CD-ROM has the opera all present there as information, whether it is being played on the speakers or not. Nothing need be added to complete the opera, but only to translate it into audible form.

Given these considerations, it is difficult to see how there cannot be a metaphysical necessity that the human soul is present right from the beginning. This argument suggests that it may, after all, be within the Church’s competency to define dogmatically the exact moment of the beginning of human life.

Where there is life, there is soul. One can add: where there is a process of life directed toward the goal of forming a man, (a) there is at some point the form of man, his soul, and (b) the entire process must be judged in continuity with its goal and as sharing already in the metaphysical status of its goal. This is why it is fully consistent for the Catholic Church to say (a) we must always act exactly as we do when a human person is present, and (b) no matter what else can be said, the entire process of human generation is mysterious, sacred, and inviolable, for its goal is the procreation of the image of God. That, it seems to me, is the crucial point; there is no need for any further knowledge.

Finally, I would say that if we do not return in a serious way to the Aristotelian philosophical analysis of soul and body, the whole modern discourse about human rights, human dignity, and the human person will become purely rhetorical and eventually meaningless, or worse, a vehicle for enforcing errors, as we have seen with the European Union and the United Nations. Hence, the Church has never been afraid to speak of the immortal soul and the body as the co-principles of man, a teaching we see reaffirmed explicitly in Pope John Paul II’s greatest encyclical, Veritatis Splendor.

[i] One has to say “ordinarily” because Thomas held a different view about the Incarnation of the Word, whose human nature, he believed, had to be present in its wholeness from the first moment.

[ii] In this discussion, the soul is the form of the body. Wherever there is a living body, there must be a soul as the principle of its life.

[iii] If it is organic complexity that one needs for life, the requisite complexity is already there at the microcellular-molecular level. One need only think of the staggering complexity of human DNA, which, in its own way, far exceeds in patterned articulateness any subsequent organ at the level accessible to us in our ordinary experience. Now, Aquinas could know nothing about that in the thirteenth century, and indeed he would have thought it completely contrary to experience to assert that what looks like a spot of blood is, in reality, an enormously elaborate system of data. In this regard, what I would say is that Thomas’s principles are, as always, sound, but his (or his age’s) scientific knowledge is wanting.

[iv] Some subtle questions do arise (e.g., with twinning, where it seems you have one person first and then a second soul is subsequently infused), but they can be resolved by a thoughtful application of the act-potency distinction.

[v] For an extensive critique of the modern misconception of freedom as displayed in the pro-abortion mentality, see Joseph Ratzinger, “Truth and Freedom,” Communio 23.1 (Spring 1996): 16–35, available here.

[vi] This also explains why the Church traditionally opposed cremation: at least some of the bodily remains of a person will someday be reunited with the soul that once informed them, therefore they must be treated with respect rather than like rubbish to be discarded. The veneration of relics rests on a similar foundation: these bodily parts were the instruments of justice by which the now blessed soul achieved Heaven; thus, they are holy by association and by anticipation.

[vii] Incidentally, it can easily be seen that one of the basic errors typical of the modern scientific mentality is the denial, or more often ignorance, of the act-potency distinction. It leads to a simplistic “either/or” logic: either the baby in the womb is fully and perfectly human or he is non-human and therefore dispensable, as if to say: there is nothing “in between” absolute being and absolute non-being — a sort of materialistic version of Parmenides.

Image: lunar caustic via Wikimedia Commons.