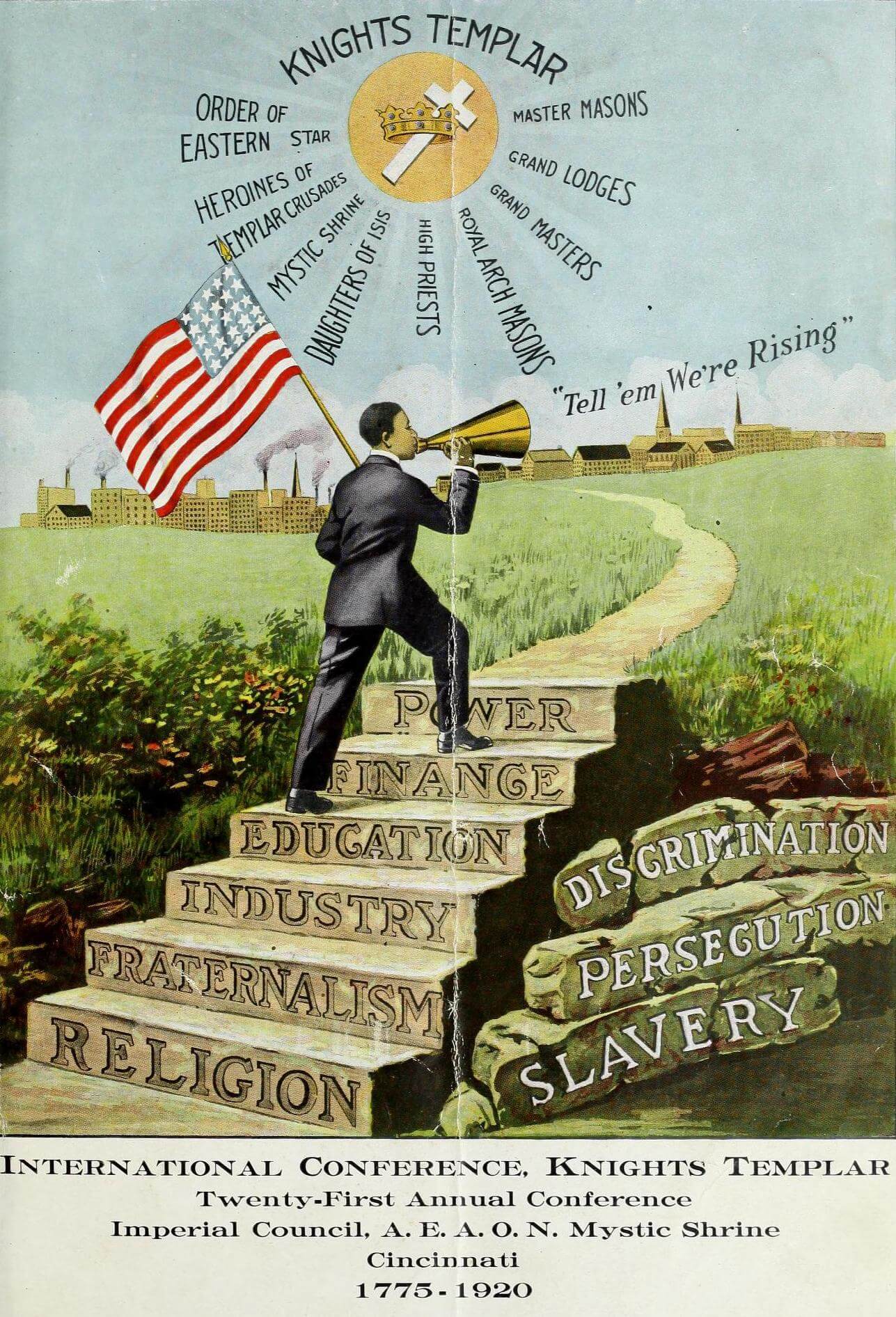

(Above): Illustration from a Prince Hall Masonic convention in 1920.

Freemasonry as Method of Subterfuge Among Black Americans

In 2003, I wrote what had soon become a groundbreaking book on the history of Prince Hall Freemasonry (the predominately Black sect of Freemasonry in America), entitled, Inside Prince Hall, which included a chapter entitled, ‘The Christianization of Prince Hall Freemasonry.’ Although I was an Agnostic-leaning Diest back then, I had to admire the culture and tradition of Protestant Christian religiosity, which the Black American sect of Anglo Freemasonry proudly evangelized, and which was the most impactful legacy of its founder Prince Hall. Now, having a clearer understanding of the devastation that Protestantism and Black bourgeoise fraternalism have had on the Black culture in the United States, here, I offer an amendment to that chapter.

This essay also proposes to correct flawed scholarship among Catholics who have scantily and in error written about Prince Hall Freemasonry. For example, in 1995 (last updated 2005) Brother Charles Madden, O.F.M. Conv., wrote, “While there is the Prince Hall system of Masonry for blacks, it is not considered authentic.” In his 2006 Masonry Unmasked: An Insider Reveals the Secrets of the Lodge, John Salza wrote, “The most notable exception of universal recognition involves Prince Hall Grand Lodges, which are almost exclusively made up of black Masons. While Prince Hall Masonry subscribes to the three symbolic degrees, it does not enjoy universal recognition.”

This type of errant and uncontextualized information about the predominant sect of Freemasonry among Black Americans; that ‘they have a Freemasonry, but it’s not like White Freemasonry,’ has led to the belief that Prince Hall Freemasonry has not been prohibited by the Catholic Church, and, thereby, has created a culture within Catholicism where the enrollment into Freemasonry and its appendant Masonic bodies has systemic among Black Catholics for over a century. Even recently, Malcolm Morris, the Grand Master of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Missouri, styled himself the first-ever Catholic Grand Master of his Grand Lodge. The notion that Prince Hall Freemasonry is a type of Freemasonry that is not prohibited is idea contrary to Pope Clement XII’s explicit statement in his 1738 Papal Bull In Eminenti apostolatus specula (“The High Watch”) where he makes no exceptions for the prohibition regardless of what a sect of Freemasonry is called, “these aforesaid societies of Liberi Muratori or Francs Massons, or however else they are called . . .” To which Blessed Pius IX affirmed in his 1873 Papal Encyclical Etsi Multa (“Although Many”) that the prohibition against Freemasonry is global, not regional: “Teach them that these decrees refer not only to Masonic groups in Europe, but also those in America and in other regions of the world.”

History of Prince Hall Freemasonry as a Recognized Anglo Sect

Researchers have established that early in 1775 a British infantry regiment, the 38th of Foot (South Staffordshires), was stationed in the vicinity of Boston, Massachusetts, and this regiment had a lodge chartered by the Grand Lodge of Ireland, Lodge No. 441.[1] The regiment had previously served in the West Indies until 1765, and then, after a period back in Britain, was stationed in Nova Scotia and the American colonies.[2] It left Boston on March 17, 1775. Among its ranks was John Batt, who served from 1759 until his discharge at Staten Island (New York) in 1777. He was a member of Lodge #441, and was recorded on the rolls of the Grand Lodge of Ireland in May 1771.[3] It is generally agreed that on March 6, 1775, fifteen civilians were initiated in Lodge No. 441, with John Batt presiding as Master, and that these civilians were Blacks from the Boston area. They are named as Prince Hall, Peter Best, Cuff Bufform, John Carter, Peter Freeman, Forten Howard, Cyrus Jonbus, Prince Rees, Thomas Sanderson, Buesten Singer, Boston Smith, Cato Spears, Prince Taylor, Benjamin Tiber and Richard Tilley (names are subject to spelling variations).[4] It would appear that some received all three degrees (probably on the one occasion), some two degrees, and some only the first degree.

When the regiment left the Boston area only eleven days later, the fifteen civilian members of the lodge were left behind. A letter or letters written by Prince Hall stating that the fifteen Masons were given a permit (probably what is otherwise known as a dispensation) to meet, to celebrate Saint John’s Day, and to bury their dead ‘in manner and form.’ The indications are that in 1776 (during the American War of Independence, when communication with the ‘home’ Grand Lodges in Britain would have been well-nigh impossible), these fifteen Masons formed themselves into a lodge, which they called African Lodge #1, under the Mastership of Prince Hall.8 When the war was over, they petitioned the Grand Lodge of England (Anglo/Moderns) for a charter, which was granted on September 29, 1784 and received, after several delays, on April 29, 1887.[5] The warrant, which is said to be in the standard form of the period, names Prince Hall as Master, Boston Smith as Senior Warden and Thomas Sanderson as Junior Warden. There is a record of communication between African Lodge #459 and the Grand Lodge of England through 1802, and African Lodge was renumbered #370 in 1792.

In 1797, African Lodge began to act contrary to the limits of its warrant; rather, acting as a Grand Lodge itself, it issued two warrants for new lodges; African Lodge 459B in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Hiram Lodge (without a number) in Providence, Rhode Island, and this practice of a subordinate lodge warranting other subordinate lodges continued for decades. By 1815, the regular Black lodges of Philadelphia came together to establish African Grand Lodge and in 1827, after several unanswered correspondences to their Mother Grand Lodge, the African Lodge of Boston declared itself independent and formed itself into a Grand Lodge. From here, Prince Hall Freemasonry spread throughout the United States; predominantly, in conjunction with the growth of Black Protestant Christianity, and, for about a century, would serve as the pinnacle of Black bourgeoisie leadership and excellence. Nearly every iconic figure in Black America prior to 1920 was a Prince Hall Freemason.

Despite its unusual formation, and acknowledging that human prejudices, bigotry, and racism, played an overarching role in the two sects of American Freemasonry (one Black, one White), since 1989 Mainstream predominately White Grand Lodges and Prince Hall Grand Lodge had exchanged recognition and visiting rights with each other, and in 1994, the United Grand Lodge of England adopted a resolution declaring the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Massachusetts regular and recognized. Therefore, at the dating of their works (1994/2005), both Madden and Salza were incorrect and could have done less harmful research.

Prince Hall Freemasonry as Just Another Protestant Denomination

From the outset, as the first Worshipful Master of African Lodge #459, Prince Hall preached a Freemasonry that was flamboyantly Christian, and one which flatly ignored the prohibitions against sectarianism, according to Anderson’s Constitution of 1723 (the founding constitution of Freemasonry) where religion was consigned to the category of “their particular Opinions.” The best evidence of the type of fraternal religion for Black men, under the guise of Freemasonry, that Prince Hall envisioned for this new society is found in his John the Baptist Feast Day Charges (i.e., lectures given from the Worshipful Master to the craft) on June 25, 1792 and June 24, 1797:

- Prince Hall’s Charge, 25 June 1792

Query, whether at that day, when there was an African church, and perhaps the largest Christian church on earth, whether there were no African of that order; or whether, if they were all whites, they would refuse to accept them as their fellow Christians and brother Masons . . .

- Prince Hall’s Charge, 24 June 1797

But my brethren, although we are being here, we must not end here; for only look around you and you will see and hear a number of our fellow men crying out with holy Job, have pity on me, O my friends, for the hand of the Lord hath touched me. And this is not to be confined to the parties or colours; not to towns or states; not to a kingdom, but to the kingdoms of the whole earth, over whom Christ the king is head and grand master.

- Prince Hall’s Charge, 24 June 1797

Thus, we see, my brethren, what a miserable condition it is to be under the slavish fear of men; it is of such a destructive nature to mankind, that the scripture everywhere from Genesis to the Revelations warns us against it; and even our blessed Saviour himself forbids us from this slavish fear of man . . .

- Prince Hall’s Charge, 24 June 1797

My brethren, let us pay all due respect to all whom God hath put in places of honour over us: do justly and be faithful to them that hire you, and treat them with that respect they may deserve; but worship no man. Worship God, this much is your duty as Christians and as masons.

—

It was this type of Protestant Christian ethos of Freemasonry that attracted countless prominent Black Christian pastors and evangelists into Freemasonry from the beginning. Most notably among this group was Bishop Richard Allen (1760 – 1831), founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (A.M.E.) and first Grand Treasurer of the African Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania. There was Reverend John Marrant (1755 – 1791), one of the first Black preachers and missionaries in North America, who on June 24, 1787, just three months after his initiation into Freemasonry, delivered a sermon on the Feast of Saint John the Baptist in which he declared, Black people as “an essentially distinct nation within a Christian universalist family of mankind.” There was also Reverend Thomas W. Stringer (1815 – 1893), ordained in Richard Allen’s A.M.E. Church. Stringer was one of the most accomplished churchmen, politicians, and Freemasons of his day; a Deputy Grand master in two Grand Lodges, the first Grand Master in two Grand Lodges, and a state senator for Mississippi. Stringer spent his life working up and down the Underground Railroad, from Canada to Mississippi, organizing A.M.E. Churches, schools, and Masonic Lodges; oftentimes all meeting in the same building.

Leaders shape the culture of an organization in their own image, and organizations attract people according to their image and culture. Prince Hall Freemasonry was shaped by men who felt that Freemasonry and Christianity were one and the same, and in this spirit, they attracted men who were Protestant Christians and who supported the beliefs of the culture. From Prince Hall to the many ministers that have been leaders of the Prince Hall Freemasonry, until today, there have been many individual influencing factors that have contributed to the Christianization of Prince Hall Freemasonry, but none greater than the fact that for most of its history, Black America had depended on the Protestant Church for its well-being. Until the emergence of political parties as the new pseudo-religion, the leaders in the Black communities had always been religious figures and, from slavery until integration, all the Black community had to lean on was the Church and the Lodge—and these bodies often met in the same facility. This was the Black American experience.

Prince Hall Freemasonry Clashes with the Catholic Church

Being that Freemasonry and other secret societies were just part of the ordinary milieu of Black America from the beginning, it made sense that Rome, post-Civil War, was highly interested in supporting Black Catholics in America and evangelizing all free Black Americans, albeit consistently rebuffed by most American Bishops, inquired of Father John E. Burke of New York who had organized the Catholic Board for Negro Missions, about his opinion on how to best attract Blacks to the Catholic faith. Including statistics and other information about the issue, Fr. Burke reported back to Rome in October of 1912 that many Blacks had joined secret societies, which made them unworthy to receive the Sacraments.[6] In other words, Prince Hall Freemasonry and organizations like it had become a type of subterfuge to the salvation of many Black Americans. Fr. Burke’s recommendation that these Black Freemasons be allowed to maintain their membership with the permission of the Holy See, because they depended on the financial benefits from the lodge and because Black Freemasonry was not as harmful as White Freemasonry was scandalous and damaging to souls.[7]

More can be said about the negative influence that Prince Hall Freemasonry has had on Black America, but it suffices to conclude here to point out how consistent this Anglo Sect of Freemasonry has been with the overall machinations of Freemasonry, even though it has been outwardly Christian.

What we have seen is that Freemasonry is a handmaid of Protestantism because they are both children of the heresy of indifferentism. For this reason, Freemasonry has always spread much faster and has been much more deeply ingrained in Protestant countries than anywhere else. Such was the very fertile soil that Black America, largely Protestant, afforded to Prince Hall Freemasonry. The way that Prince Hall Freemasonry used preachers to soak the Black community into false promises of Freemasonry, was no different than how Margaret Sanger used Black preachers to soak the Black community into the lies of how birth control eugenics could benefit them.

Freemasonry always leaches itself onto children and families through education and associations for the children and wives of Freemasons. Such is the case with Prince Hall Freemasonry which has established more schools for children and more associations for children and women than any other sect of Freemasonry. The fact that there are more Black Americans who can point to a Freemason or an Eastern Star in their genealogy than point to a Catholic descendant is a grave tragedy.

What is more of a tragedy is the large number of Black Americans who can point to a Catholic in their family who is also a Freemason or an Eastern Star, but from Philadelphia to New York, to Maryland, to New Orleans, Chicago, Saint Louis, and Kansas City, I estimate that there is a larger percentage of Black Catholics who are Freemasons than there are non-Black Catholics who are in the grave sin of Masonic association.

The clash here is one of culture. There is a culture among cradle Black American Catholics who treat the dogma of the Church as a mere opinion and there is a culture in the Catholic Church that has never had the inclination or the energy to root Freemasonry out of the Church. There is also the lie of Fr. Burke and Catholics authors who have addressed this topic by insisting that Black Freemasonry is not as harmful as White Freemasonry, as if that was ever the teaching of the Catholic Church. Just because for most of its history, Prince Hall Freemasonry was segregated, never meant that it was not leading people to Hell.

[1] Draffen, G: Prince Hall Freemasonry in (1976) Ars Quatuor Coronatorum 87:70 @90.

[2] Wesley, Charles H.: The History of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Ohio 1849–1971, Associated Publishers, Washington DC (1972), 5. He suggests that Prince Hall may have known some of the soldiers prior to being stationed in Boston, since the regiment had been stationed at Antigua, Guadeloupe and Martinique, and some Black men were recruited to its ranks and were sent first to England, then to Nova Scotia and to the English colonies in America.

[3] Davis, Harry E. A History of Freemasonry Among Negroes in America, United Supreme Council Northern Jurisdiction, Philadelphia (1946), 31; Draffen, op. cit., 73.

[4] Draffen, G., op. cit., p 72.

[5] Upton, William H: Prince Hall’s Letter Book in (1900) AQC 13:56; reproduced in facsimile by Wesley, Charles H: Prince Hall Life and Legacy, 2 edn, United Supreme Council Southern Jurisdiction Prince Hall Affiliated, Washington DC (1983), op. cit., 57–9; he gives the date of issue of the warrant as 20 September, but all the alleged transcripts of the warrant say ‘29th.’

[6] Davis, Cyprian. The History of Black Catholics in the United States (The Crossroad Publishing Company, New York. 1990), 199 – 201.

[7] Ibid., 201.