Editor’s note: The following comes from Genevieve Rose Kwasniewski, a homeschooled high school student who enjoys reading the lives of the saints, composing music, and playing the organ at her local traditional Latin Mass.

I want you to know what I went through by volunteering for the Front. God made me feel with absolute certainty – I suppose to increase the merit of the offering – that I shall be killed. The struggle was hard, for I did not want to die; not indeed because I am afraid of death, but the thought that I could never again do more for God or suffer for Him in heaven made the sacrifice too bitter for words. [1]

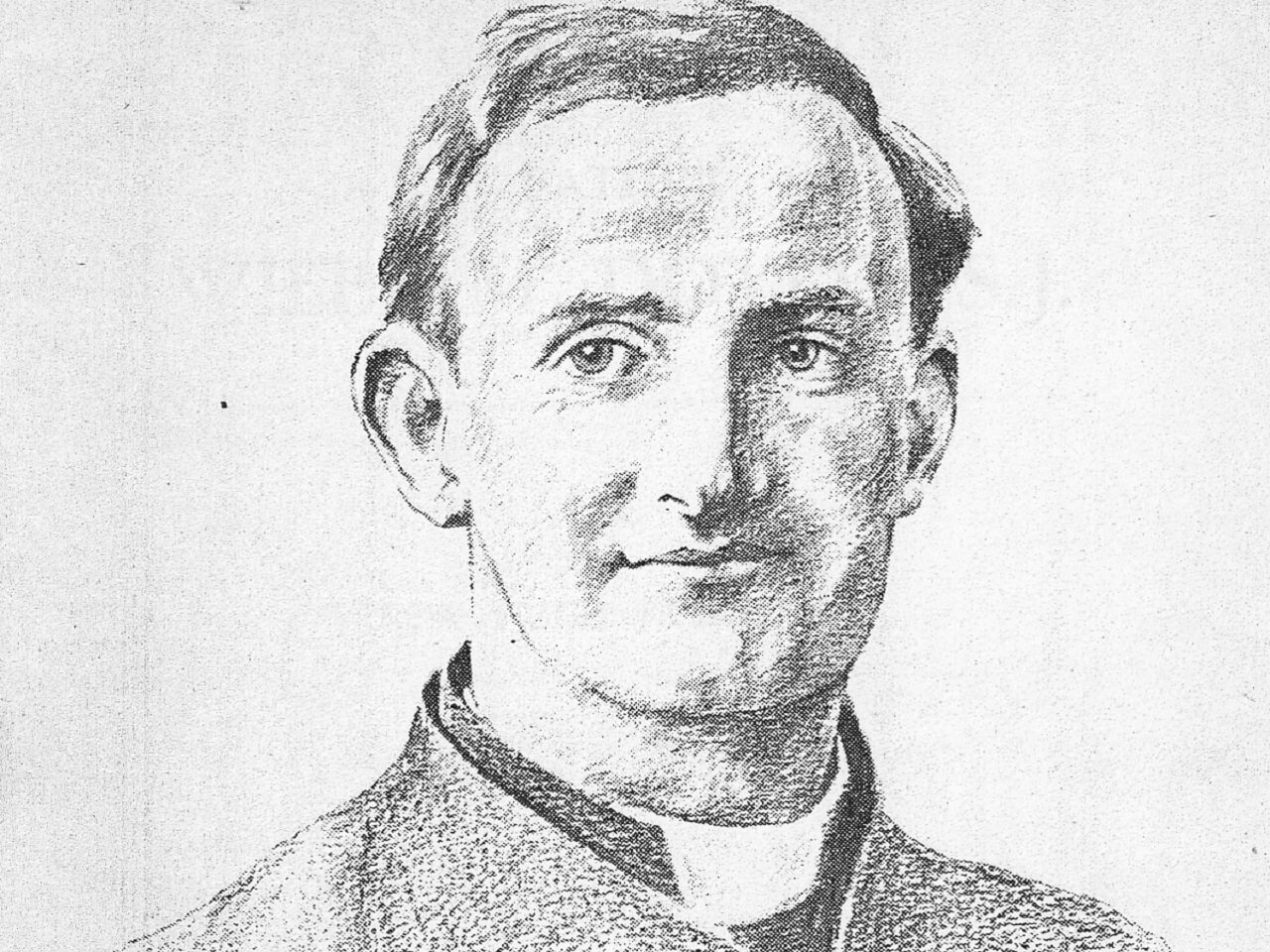

Thus wrote Fr. Willie just before he went to the war (World War I), where he spent three years in heroic service of his regiment before he became, as he had always longed for, a martyr of charity. At the front he worked with all his strength, spending himself in prayer and penance for love of the Blessed Sacrament and the Sacred Heart, and for the conversion of sinners, as he had done for the whole of his priesthood.

William Gabriel Doyle was born in Dublin on March 3, 1873. He was the youngest of seven children. By the time he was nine, Willie had begun begging for the poor and giving his money away freely to them. Once, he was visiting an old widow when he noticed that the house was dirty. Willie promptly went off to buy some lime and a brush, with which he whitewashed the whole house. He reminded the poor of spiritual things and did his best to bring those fallen away back to the Church. He spent eight hours praying by the deathbed of an alcoholic who had refused the last rites, until, just before the old man died, he asked for them. Such acts of charity characterize all of his early life.

At age eleven, he went off to “college,” where he stayed till he was seventeen. He planned to join the diocesan seminary, but in the fall of that year, he visited his older brother, a Jesuit novice, with whom he began to discuss religious life. He was so shaken in his plans that he accepted some books from his brother. After a few months, he made his decision. He was joining his brother as a Jesuit.

During the novitiate, his health broke down, and he was sent home, seemingly for good. But the provincial superior intervened, and Willie made his vows in August 1893. We have from this time a little document he wrote on May 1, promising his “darling heavenly Mother” that he would begin his life of slow martyrdom by hard work and self-denial and begging her to make him a Jesuit martyr. Part of it is written with his own blood. For the next fifteen years, Willie studied theology and philosophy and taught in Belgium and Ireland. He was finally ordained in 1907.

One of Fr. Willie’s main apostolates was preaching missions, which he gave to communities of nuns and at any parish that would take him. During his priestly life, he gave 152 missions and retreats – and his preaching was very effective. A Protestant lady who was attending a mission of his, after the first few sermons, refused to go again, because she said she didn’t want to be converted.

Fr. Willie’s love of souls was great, as this excerpt from his diary reveals:

Recently at Mass I have found myself at the Dominus Vobiscum opening my arms wide with the intention of embracing every soul present and drawing them in spite of themselves into that Heart which longs for their love. “Compel them to come in,” Jesus said. Yes, compel them to dive into that abyss of love. Sometimes, I might say nearly always, when speaking to people I am seized with an extraordinary desire to draw their hearts to God. I could go down on my knees before them and beg them to be pure and holy, so strong do I feel the longing of Jesus for sanctity in everyone. [2]

Fr. Willie was constantly seeking after the most hardened sinners, the “big fish,” as he called them. As when he was a boy, he would spend hours praying for sinners, often in their own houses. Many times he was forcefully ejected, but the next day he was there again, never giving up. There were days he spent hearing Confessions from prior to dawn until late at night.

Fr.Willie also worked tirelessly as a spiritual director, and his words are just as comforting to us now as they were when he first wrote them.

He sees what a little child you are, and how useless even your greatest efforts are to accomplish the gigantic work of making a saint. But this longing, this stretching out of baby hands for His love, pleases Him beyond measure; and one day He will stoop down and catch you up with infinite tenderness in His divine arms and raise you to heights of sanctity you little dream of now. [3]

I want you to make a greater effort to see the hand of God in everything, and then to train yourself to rejoice in His holy will … say you want a fine day, and it turns out wet, don’t say “Oh, hang it,” but give Our Lord a loving smile and say: “Thank You, my God, for this disappointment.” [4]

This is writing worthy of a St. Thérèse. I have given two quotations; I had difficulty not putting in twenty.

Even when he was a child, Fr. Willie longed and prayed to be a saint. At the beginning of his priesthood, he received a vision. He saw Our Lord with His cross on His shoulders. Before them was a thorn-choked path, and Our Lord asked Fr. Willie if he could follow that path and take up the Cross. Fr. Willie responded yes and asked Jesus to drag him through the thorns. He subsequently put this vision into practice with earnest penances. He fasted most of the time. He went on pilgrimages to local shrines barefoot in the middle of the winter. He bathed in ice-cold water in the middle of the night. This was, of course, a specific calling, perhaps not meant for most, but beautiful in its austerities, for it shows how much Fr. Willie strove to be an alter Christus, resembling Jesus in His suffering.

He was deeply devoted to the Blessed Sacrament, rising to spend time before the Tabernacle in the small hours of the night. He wrote that when he was giving out Communion, he often seemed to feel how glad Jesus was to leave his hand, most especially for children. Once, he had to stay at a house that didn’t have a chapel, so he got up in the middle of the night and walked about ten miles to spend time with his hidden God.

The Most Blessed Sacrament did not let him go unrewarded. On one occasion, he had an “accident” – in reality, he had inflicted a terrible penance on himself – and the doctor was in despair of his life. But, being Fr. Willie, he promptly got up and, with difficulty, celebrated Mass, and as soon as he received Holy Communion, he was completely healed.

Boundless was Fr. Willie’s love for Jesus, and at times he could not contain it. He seems to have been pierced with Divine Love like St. Teresa of Avila:

O Jesus, Jesus, Jesus! Who would not love You, who would not give their heart’s blood for You, if only they realized the depth and breadth and the realness of Your burning love? Why not then make every human heart a burning furnace of love for You, so that sin would become an impossibility, sacrifice a pleasure and joy, virtue the longing of every soul, so that we should live for love, dream of love, breathe Your love, and at last die of a broken heart of love, pierced through and through with the shaft of love, the sweetest gift of God to man! [5]

This love to the point of folly could not always be contained, and so he would often embrace the Tabernacle and press his heart against its door.

In 1915, Fr. Willie volunteered to be a war chaplain, instead of being a missionary in the Congo, which he had asked for during his novitiate. He was summoned about a year after he volunteered. He had the privilege of carrying the Most Blessed Sacrament in a pyx hung around his neck, an honor he considered full recompense for all his labors. Far from relaxing his penances because of the hardships of war, he continued with them, regularly spending whole nights in adoration after exhausting days of work. Officially, all he had to do was tend to the wounded and dying in the infirmary, but that was not enough for his love of souls. Far too often for his own safety (about which he cared nothing when souls were at stake), he ran out onto the open battle field “like an angel of mercy” to anoint dying soldiers and bring back the wounded. Whenever there was a particularly heavy shelling, soldiers would flock to him, and his dugout would be packed full, so convinced were they that he was invulnerable. Their confidence was not misplaced. Bombs could drop four feet away from him, killing everyone else instantly, but he would be without a scratch.

This could not last forever, and Fr. Willie knew it. He had offered his life to the Sacred Heart, and his offering was accepted. Fr. Willie was killed during the battle of Ypres on August 16, 1917, when he was carrying a wounded soldier to the infirmary. The soldiers at first could not believe that he had been killed. When finally convinced, they began to cry openly. A thief who had been a soldier in the war was attempting to rob Fr. Willie’s home several years later, and was going through his father’s drawers, when he discovered Fr. Willie’s memorial card. When the thief saw that it was of Fr. Willie, he kissed the photo, put it in his pocket, and ran, taking nothing else!

Thus Fr. Willie died and was brought to Life, at the age of forty-four, having loved Jesus and having loved Him to the end. Once he got to his “old armchair up in heaven,” he wasted no time in getting to work on earth, for his story spread quickly, and after only fourteen years, around 6,423 favors through his intercession had already been reported.

Given how wonderful this priest-hero is, I am happy to be able to report to OnePeterFive readers that a brand new book has appeared: To Raise the Fallen: A Selection of the War Letters, Prayers, and Spiritual Writings of Fr Willie Doyle, SJ (Dublin: Veritas, 2017). This book is a good introduction to Fr. Willie for those who have never met him, and a good guide to his own writings for those who may have already read the hefty O’Rahilly book or one of the others on his life and spirit. The book is 192 pages long – not too much to turn off the casual reader but not too short to be skimpy. For the most part, it is a collection of Fr Doyle’s own writings – letters from the battlefront, personal spiritual notes relating to his own interior life, a selection of his writings on various aspects of the spiritual life arranged according to theme, writings on vocations, some of his personal prayers including a meditation on the Gospel, plus a series of testimonies about him. Some of the material in the book has never been published before. It also includes a biographical essay as well as commentary introducing his private spiritual notes to put them in context.

To read more about Fr. Doyle, visit www.fatherdoyle.com.

[1] Fr. Willie Doyle & World War I, A chaplain’s story. The incorporate Catholic Truth Society, London, 2014, pg. 29.

[2] Alfred O’Rahilly, Fr. William Doyle, S.J. (London: Longmans, Green & Co, 1922), 98.

[3] Ibid., 181.

[4] Ibid., 189.

[5] Ibid., 104.