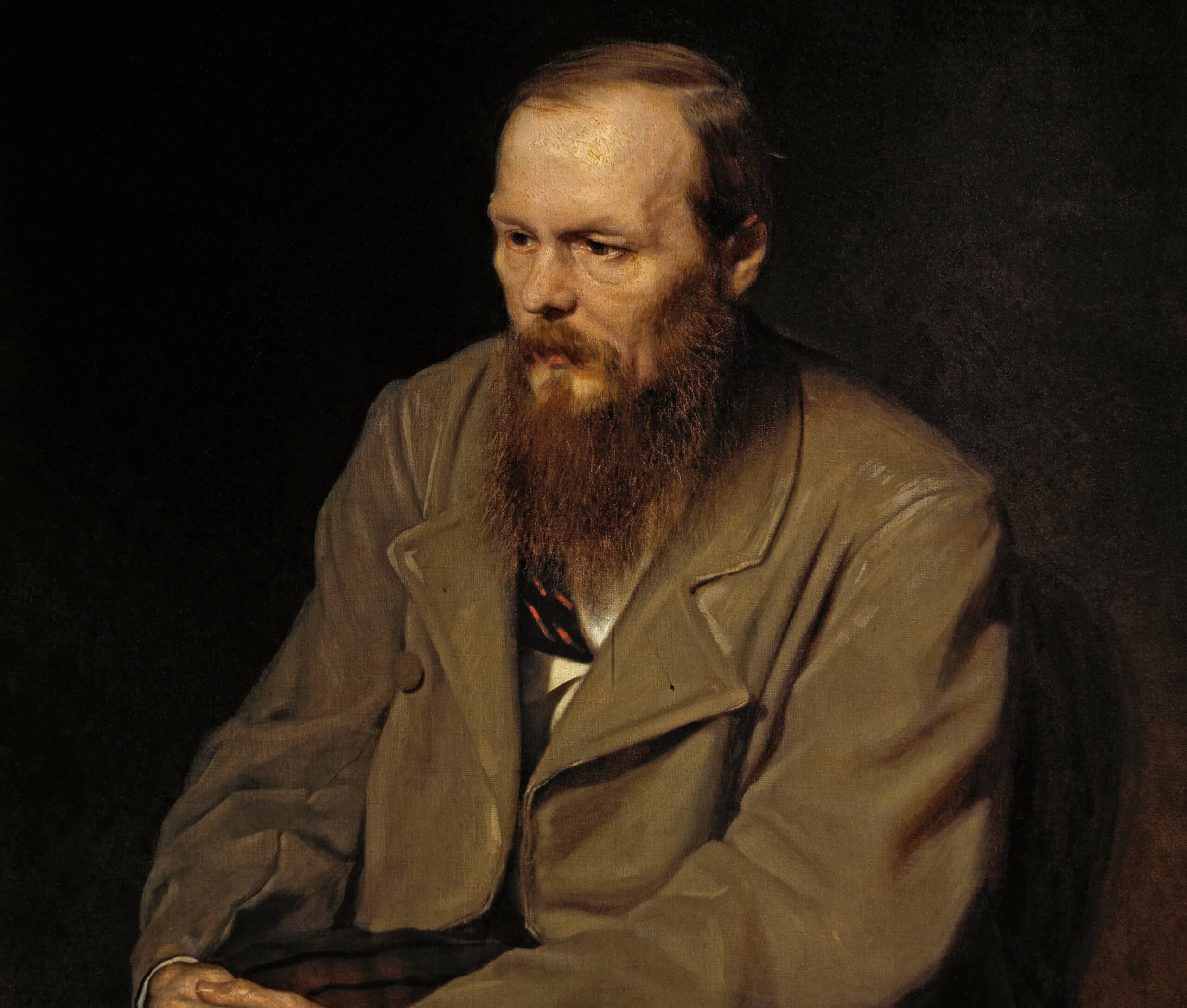

Above: Fyodor Dostoevsky by Vasily Perov

The recent deaths of former Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev and Orthodox Metropolitan Kallistos (Timothy) Ware brought forth eulogies, remembrances, and commentary in both the secular and religious spheres. Gorbachev was the face of the end of Communism, while Ware was likely the premier English language writer and explicator of the Eastern Orthodox faith. Gorbachev presided over the end of one portion of Russia’s recent history when I, like many of us, (mistakenly) thought Communism was dead. Ware’s The Orthodox Church, The Orthodox Way, and translations of The Philokalia introduced several generations of English speakers to the faith to which he converted. Although he later became a prelate in the (Greek) Ecumenical patriarchate, he began his journey through the friendship of Russian émigrés in Britain and in the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR).

Ware influenced my spiritual journey. As I groped toward an understanding of the apostolic church, his writings in their clarity, concision, and certainty without triumphalism, drew me to the East. During my twelve-year sojourn in Orthodoxy, I had the great privilege of hearing Met. Kallistos speak at a university near my home. He was charming and erudite, as one might expect from his books and academic background. Nevertheless, over the years Ware’s incipient liberalism gradually came to the fore. As Fr. John Hunwicke noted in a blog post about his fellow Englishman, Ware’s positions on contraception and ordination of women showed a growing divergence from Tradition. That openness to alterations in Tradition are not an aberration in the Orthodox sphere. Divorce and adulterous remarriage has been tolerated and blessed (albeit penitentially) in “Orthodox rites” for centuries, and there is a growing softening of opposition to homosexuality (notwithstanding our own very recent problems with the annulment crisis). And yet many tradition-minded Catholics seem to think Orthodoxy is a refuge from the culture and dogma wars within Catholicism. To understand why, I think we must look at a crucial issue of our time, the Fatima message and (Orthodox) Russia.

The Many Errors of Russia

Our Lady’s appearances at Fatima have stirred up the Catholic Church since 1917. More than a century later, the debate over the Fatima messages, their content, and their interpretation, rages on. A new sense of urgency envelops the debate as the Russian invasion of Ukraine grinds along and after a problematic consecration by Pope Francis. Perhaps a good place to start is to ask: what are the errors of Russia mentioned by Our Lady?

For decades, the answer was clear on at least one of the errors: Communism. But errors is plural, so what are the other Russian errors? A survey of the last one-hundred and fifty years could produce the following list: schism, Atheism, nihilism, phyletism (the ecclesiastical heresy which subordinates the Church to an ethnicity), pan-Slavism, existentialism, caesaropapism, and the cult of personality. While some of these may have originated elsewhere, Russia was the nurturing womb from which these errors sprang forth to tear at the fabric of God’s world. There are many political explanations for this, but I think a better place to find answers lies in the writings of novelists and spiritual writers, beginning with Dostoevsky.

Dostoevsky’s life and thought embody tensions within 19th century Russia, and his examination of ideas, ideologies, and all-around godlessness presciently depicted the horrors of Modernism. He began his adult life and career under the influence of Romantic and Liberal ideas, but a series of events and their attendant suffering impelled a growing spiritual and philosophical conservatism. He wrote movingly about human freedom and saw with perspicacity the corrosive effects of various godless movements on the Russian soul and psyche. His early works, such as Poor Folk, with their depictions of poverty, despair and social ferment, might be compared to Dickens; but, after his release from imprisonment, so movingly described in The House of the Dead, Dostoevsky’s work went deep into the human heart.

The Literary Genius of Dostoevsky

On the one hand, the author forcefully presents the deadly effects of sin (Crime and Punishment), the utter cynicism and brutality of nihilism (Demons), the hurts of illegitimacy (A Raw Youth and The Brothers Karamazov), the hopelessness of gambling addiction (The Gambler), and foibles of social class (The Idiot). On the other hand, some of his books have problematic aspects, such as Notes From Underground, with its proto-existentialist anti-hero perversely exercising free will to say no to his fellow humans and God.

Dostoevsky’s magnum opus is his last novel, The Brothers Karamazov, a tale of parricide, greed, atheism, human kindness and cruelty, and much more. In spite of its many, many virtues, the novel contains three prominent Russian errors: schism/anti-Catholicism, Atheism, and ethnocentrism. In an early conversation at a monastery, one monk lectures some visitors:

[T]he church is not to be transformed into the state. That is Rome and its dream. That is the third temptation of the devil. On the contrary, the state is transformed into the church, will ascend and become a church over the whole world—which is the complete opposite of Ultramontanism and Rome… and is only the glorious destiny ordained for the Orthodox Church. This star will arise in the east!

The book’s infamous section on the Grand Inquisitor portrays the Roman Church as anti-Christian and materialistic, denying Christ and His message in favor of supplying weak humans with bread, not the Eucharist and salvation. Dostoevsky also caricatures Polish characters as buffoons, a tired Russian prejudice that shows up in more than one of his books.

The Tortured Russian Soul

Dostoevsky’s works make it clear that whatever noble impulses may inhabit the Russian soul, external ideologies have warped those impulses. The utopian ideas of Dostoevsky’s dreamers end up manifested in Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag. Less than a century separates the Underground Man from Ivan Denisovitch.

The Russian Revolution not only helped spread Marxist-Leninist Communism, it sent other errors into the world: social and political errors like the Atheist libertarianism of Ayn Rand; literary errors like Nabokov’s Lolita; ecumenical errors like the accommodation offered Orthodoxy at Vatican II, where Russian church observers (later confirmed as KGB operatives) came to the council in return for no denunciation of Communism in the conciliar documents. But there are remedies available.

As a voice against Communism in general, Ven. Fulton Sheen has no peer. An answer to religious threats from Russia is found in the books by Catherine De Hueck Doherty, who wrote so movingly about the Russian faith of her youth but fulfilled in union with Rome. Rand (forced from Russia due to her politics) is ably countered by the personalism of Russian dissident (and later exile) Zamyatin in his novel We. And the rejoinder to Russian schism is most convincingly given by Dostoevsky’s disciple, Vladimir Soloviev, in both The Russian Church and the Papacy and “A Story of the Anti-Christ.” And then, there is J.R.R. Tolkien.

I was about thirteen when I first read Tolkien. It was during the depths of the Cold War (1970s) with its attendant fears of nuclear war, and The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings supplied a teenager with a story of good versus evil… and good won! My as-yet unformed thinking could not quite grasp the significance of Tolkien’s chapter on “The Scouring of the Shire.” It was only recently, when the reality of Communism’s resurrection struck home, that I apprehended Tolkien’s wisdom. We may have “won” the Cold War, but we didn’t stand up to the Communists at home.

Concerning Gorbachev’s post-soviet legacy, David Satter writing in The Wall Street Journal makes the harsh assessment that “the moral and legal vacuum he left behind spawned a criminal oligarchic regime in Russia that used terror to stay in power and launched a full-scale war against Ukraine.” In The Devil’s Final Battle, edited by Fr. Paul Kramer (2010), Gorbachev’s post-Soviet work and foundation is scrutinized and shown to be corrosive, un-democratic and anti-Christian. “Gorbachev, a man who admits he is still a Leninist and whose tax-free foundations are promoting the use of abortion and contraception to eliminate five billion people from the world’s population” (98). Ware’s legacy may not be so morally problematic, but his apologetics for Orthodoxy, while seemingly irenic, contributed to making a schismatic entity sound attractive to Westerners searching for a spiritual home. The Benedict Option author Rod Dreher is just one high-profile example of a Catholic turning from Rome and toward the East.

What can be done? Repent, for the Kingdom of God is at hand. We have the hope of eternity, but that doesn’t excuse us from duty in the present crisis. Is it too late? Will we be like the Numenorean queen Tar-Miriel, vainly trying to reach the sanctuary to intercede for her people, only to be swallowed up by a destroying wave? Or might we be fortunate enough to turn things around and defeat Mordor and its allies?

Soloviev, in Russia and the Universal Church, anticipating the current crisis of a slavish Russian Church’s endorsement of unprovoked war against Ukraine, wrote: “It has lately begun to be realized in Russia that a merely national church, left to its own resources, is bound to become a passive and worthless instrument of the state, and that ecclesiastical independence can only be ensured by an international center of spiritual authority.” But in his telling of the end of history in “A Story of Anti-Christ,” the brave martyr Pope Peter II stands up for Christ, is resurrected by the hand of God, and leads the former schismatics into full union with Rome, after which the culmination of the ages unfolds. Let us pray it may be so.