In the past, Western Catholics have at times tried to force their own discipline on Eastern Catholics (the name of Bishop John Ireland still haunts the conversation). We now recognize that this was a mistake, and one that is not likely to be repeated, given the correct insistence that Catholicism thrives within a diversity of rites and disciplines.

At the same time, it should come as no surprise that Latin-rite Catholics have developed, over the course of many centuries, a positive understanding, and with it a substantive defense, of the practice of clerical celibacy. For us, it is not just “a discipline”; it has profound theological and spiritual foundations that are recognized and advanced in formal magisterial documents. To contradict the Western tradition on this matter would be tantamount to calling into question Catholicism as a whole. The Eastern Orthodox are only too glad to do so; they already dispute papal primacy, the filioque, Purgatory, Original Sin, the Immaculate Conception, and a host of other “errors” (as they see it). But it is disedifying, to say the least, when Eastern Catholics jump on their bandwagon.

I encountered this personally in the years when I taught theology in central Europe to mixed classrooms of Latin-rite and Byzantine-rite students. The Byzantine students almost always came in with views identical to those of the Eastern Orthodox — the only difference being that they prayed for the pope in the Divine Liturgy — and only after much patient conversation could they be brought around to recognizing the truth contained in (even if not exhausted by) the Western positions and the cogency of Western responses to Orthodox apologetics. For example, one could assume, at the start of a course in Trinitarian theology, that many Greek Catholics would have a knee-jerk reaction against the filioque; by the end of the course, nearly all of them would agree that the filioque is implicit or explicit in the Greek tradition itself.

Obviously, there is much to be said on the topic of celibacy, and many books written, presenting both accurate and inaccurate material [i]. One especially helpful author is Fr. Gary Selin, whose book Priestly Celibacy: Theological Foundations (CUA Press, 2016) deserves to be better known. The subtitle is a bit misleading in that Fr. Selin does not limit himself to pure theology, but looks at the history of the question, starting from the Old Testament, proceeding through the Greek and Latin Church Fathers and councils, and prudently assessing later developments.

Starting from the celibacy of Jesus Christ, the celibacy of the Apostles John and Paul, and the common belief that the married apostles, on meeting the Lord, gave up their conjugal lives and practiced perpetual continence thereafter (it was none other than St. Peter, known to be married, who said: “Lo, we have left all things and followed you” [Lk 18:28], a statement to which Our Lord replied: “Amen, I say to you, there is no man that hath left house, or parents, or brethren, or wife, or children, for the kingdom of God’s sake, who shall not receive much more in this present time, and in the world to come life everlasting”), Fr. Selin presents evidence that deserves to be taken with utmost seriousness, not only by Latin Catholics, but also by their Greek brethren:

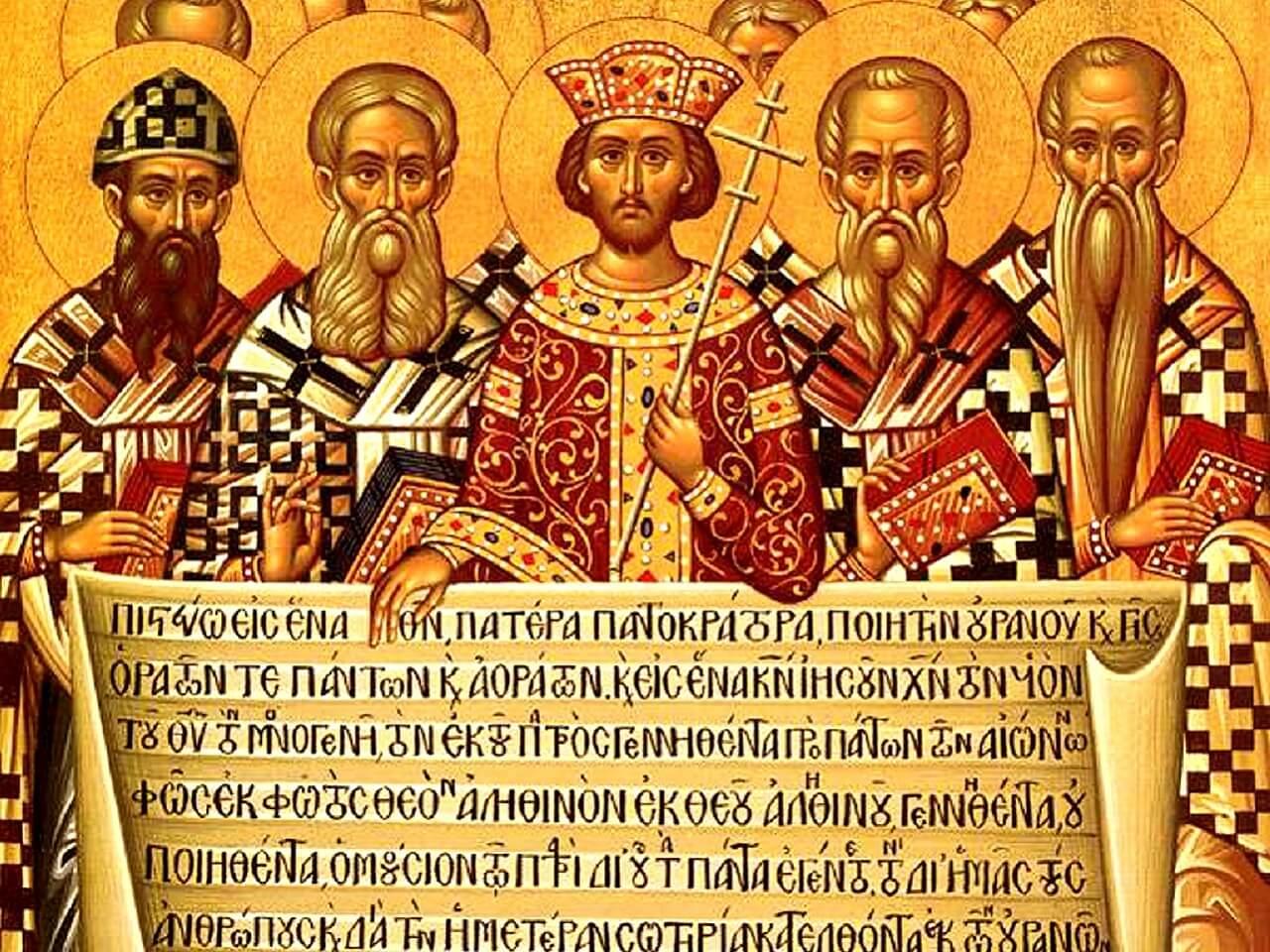

In the fourth century the first conciliar legislation concerning a consistent practice of clerical continence and celibacy appears in the Latin Church. With the lessening and eventual cessation of the persecution of the Church, provisional councils and synods were convened and record keeping was facilitated. The regional Council of Elvira (305), although convened during continuing persecution, produced the first written law in the East or in the West concerning clerical continence. In canon 33 the council required perfect continence for all married clerics under pain of deposition: “It has seemed good absolutely to forbid the bishops, presbyters, and deacons, i.e., all clerics who have a position in the ministry, to have [sexual] relations with their wives and beget children. Whoever in fact does this is to be removed from the honor of the clerical state.”

This disciplinary canon dealt with an infraction of an apparently existing ecclesial law. Neither it nor any other canon gave an explanation or justification for the law; it simply demanded obedience. It is unlikely that it was an innovation that would have deprived married clerics of a long-established right. Further, it is a characteristic of law that the origin of a legal system consists in oral traditions and in the transmission of norms that only slowly receive a fixed, written form.

The Second Council of Carthage was convened amidst the crisis of the decline of the Church in North Africa. On June 16, 390, the bishops of northern Africa gathered under the presidency of Genethlius. Bishop Genethlius said: “As was previously said, it is fitting that the holy bishops and priests of God as well as the Levites, i.e., those who are in the service of the divine sacraments, to be continent in all things, so that they may obtain in all simplicity what they are asking from God; what the apostles taught and what antiquity itself observed, let us also endeavor to keep.” The bishops declared unanimously: “It pleases us all that bishop, priest, and deacon, guardians of purity, abstain from [conjugal intercourse] with their wives, so that those who serve at the altar may keep perfect chastity.” …

The teaching of Saint Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 310–403) is significant insofar as he, an Eastern Father, gave testimony to the unity of the Western and Eastern Churches on the matter of clerical continence, rooting it in divine Revelation: “[The Church] does not accept as deacon, priest, bishop and subdeacon, be he the husband of a single wife, the man who continues to live with his wife and to beget children; the Church accepts him who, as monogamist, observes continence or widowhood; this is observed above all wherever the canons of the Church are kept faithfully.” [ii]

Then Fr. Selin touches on a sore subject in East-West dialogue:

The earliest legislation that permitted periodic continence for married clerics appeared at a regional council of the Eastern Churches, namely the Second Council of Trullo (691–692). This council upheld the traditional discipline that required bishops to be unmarried, or if married, to live apart from their wives, and continued the ban on remarriage for all major clerics whose wives had died after their ordination. However, the bishops also introduced a law that was unprecedented in previous local or ecumenical councils. Canon 13 mandated that married priests, deacons, and subdeacons were not permitted to separate from their wives and were to observe periodic rather than perpetual continence. The reigning pope, Saint Sergius I, a Syrian by birth, did not accept the Trullan canons on clerical marriage, nor did his successor, John VII (c. 650–707), who returned the Acts of the Trullan Council unsigned. However, Adrian I (c. 700–795), while rejecting the canons on clerical marriage, did accept with qualification other Trullan Acts that were free of anti-Roman canons.

The Western requirement of perfect and perpetual continence was clear from early on, and it was maintained ever more strongly, in spite of abundant evidence of non-compliance and the constant need for reform movements. The East, in contrast, opened a way of periodic continence that does not obviously harmonize with the teaching of the New Testament, the witness of the Fathers, or previous regional legislation. This real or perceived disharmony was sufficient reason for three popes to refuse their recognition of the policy. Even those who entertain skeptical views about papal primacy as it developed later on cannot deny that the pope’s endorsement of conciliar decrees in the first millennium was taken with utmost seriousness. It was seen as very important, to say the least, that the pope should “sign off on” whatever declarations, anathemas, and canons were accepted by the bishops in council.

The history of the Latin Church reveals not only a consistent exaltation and requirement of perfect and perpetual continence for the clerical state, but always a theological and spiritual interpretation of it. Clergy are to be celibate not for practical convenience (although much can be said from that point of view), but as a manner of living out the imitatio Christi expected of the alter Christus. Like fasting before Communion, celibacy is a bodily-spiritual expression of the necessary striving for ritual purity for divine worship, in which a man dares to enter the presence of the Living God on behalf of the people and to offer up a pleasing sacrifice to the Lord. Indeed, it comes to be seen as a sacramental conformity to the High Priest and Victim, a spousal conformity to the one Bridegroom of the Church, whose nuptials are celebrated on the Cross, as St. John the Evangelist reveals to us in the parallelism of Cana and Calvary. The Western theology of clerical celibacy therefore also reflects the unanimous Eastern-Western theology of episcopal celibacy: it is in the West that the identity of the presbyter as the one who assists the bishop and, later on, represents the absent bishop is most perfectly preserved.

I emphasize these points because, whatever may have still been within the realm of possibility in the year 250 or 500, it is certainly no longer possible today, after the lived experience and theological development that has passed behind us, to regard the Latin position on celibacy as solely disciplinary. A striking sign of this truth is the formulation of the 1917 Code of Canon Law: “Clerics constituted in major orders are prohibited from marriage and are bound by the obligation of observing chastity, so that those sinning against this are guilty of sacrilege.” This is not the language of a mere convention, a dictate of legal positivism.

Thus, I was pleased to see Mark Brumley post the following at Facebook:

Personally, I am happy to have the tiny number of ex-Anglican married priests we have in the Latin Rite, by way of exception to the norm of priestly celibacy. Apparently, certain folks find that paradoxical. Balthasar explained it decades ago when he spoken of them as exceptions, even while he defended the norm of mandatory priestly celibacy in the Latin Rite. He did not envision [that] men in the Latin Rite who have always lived as laymen would be ordained even by exception.

And of course Eastern Catholicism sees things differently regarding married priests. The Catholic Church, despite being overwhelmingly Latin Rite, and despite a theological valuing of priestly celibacy and not simply working from a practical administrative appreciation, hasn’t regarded the Eastern Catholic view as “communion-dividing.” That does not, however, mean Latin Rite Catholicism and the various Eastern Rites see celibacy and priesthood in the same way. They differ.

It should surprise no one, then, that the theologians and leaders of the Latin Rite will, as John Paul II did, see priestly celibacy in the Latin Rite the way the Latin Rite’s understanding of it has theologically developed. That’s part of why it’s the Latin Rite. Its theological tradition and understanding of priesthood doesn’t get gainsaid just because Eastern Catholicism has a different view or because a tiny number of Protestant ministers/priests are ordained as an exception.

Of course, exception in one circumstance doesn’t automatically justify an exception in another circumstance. Though some will insist illogically it does. And even more illogically, some will insist it’s offensive that an ex-pope/theologian and a current Cardinal defend the Latin Rite view, for Latin Rite Catholics, and don’t want to make exceptions for Latin Rite Catholic laymen who’ve never been ministers or priests to be ordained priests. It’s unacceptable to some people that the ex-pope and Cardinal want to find solutions to the problem of priest shortages in the Amazon and elsewhere that affirm the Latin Rite’s theological understanding of priestly celibacy for the Latin Rite. So unacceptable is it that they have to be condemned as anti-Pope Francis for expressing themselves on the subject, wholly in accord, by the way, with Pope St John Paul II.

Brumley is exactly right. All over the internet, one can see Eastern Catholics claiming that Cardinal Sarah’s arguments are “intemperate,” “erroneous,” “insensitive,” “offensive,” etc. Is this not a sign, richly ironic, that the East has internalized the inversion of Latinization and now refuses to be content unless the West is Easternized — or at least until the West confesses that its own practice has no decisive, compelling, and universal theological and spiritual foundation? Yet it is a basic sign of maturity in East-West dialogue when each side respects the other side’s theological interpretation of its practice (if such an interpretation exists). If the East has a truly theological argument for its married clergy, let it bring it forth, and let the West respect it and allow it to stand for the East (since we will never agree with it for ourselves); if the West, for its part, has a truly theological argument for clerical celibacy, let it be put forward without apologies and without embarrassment, and let the East respect it as a valid, if not exclusively valid, perspective.

Is this a form of doctrinal relativism? I do not think it has to be seen that way. The great Mystery of Faith uniting all orthodox Christians is lived out variously in diverse traditions, all of which remain in sacramental and ecclesial continuity with Christ and the apostles. We see such diversity in many examples: the use of leavened bread or unleavened bread, the giving of Communion under both kinds or under one kind. These traditions are defensible from different angles; they are worthy of preservation within their own context, where the meaning is (generally) understood and (hopefully) preserved from misinterpretation. This is why I have always advocated “letting Latins be Latins, and Greeks Greeks.”

It is also possible that multiple traditions can be legitimate, while nevertheless one tradition is superior, on the whole, to another — put differently, that one way is better than another because it rests on a deeper foundation or coheres better with other aspects of the Faith. This is what Western Catholics believe to be true about the Latin rule of clerical celibacy. To say it is better does not mean that the Eastern rule is wrong and must be overturned, but only that it is less good — even as asserting the superiority of the life of evangelical poverty, chastity, and obedience over the state of marriage does not entail that marriage be something evil. Marriage is still a divinely blessed sacrament, and married clergy are still clergy in the full sense of the word, empowered to do all that the clergy are divinely appointed to do.

Ultimately we have to recognize that it’s not really the Eastern tradition that inspires those Western Catholics today who seek to abolish or optionalize clerical celibacy, just as neither was it the East that inspired Paul VI’s liturgical reform, which was, in point of fact, profoundly anti-Byzantine. The roots of the Bergoglian synodal Church are to be found not in Eastern Orthodoxy, but in Modernism, itself deriving from liberal Protestantism. St. Pius X already gave his judgment: “There are some who, echoing the teaching of their Protestant masters, would like the suppression of ecclesiastical celibacy” (Pascendi Dominici Gregis 38). If we want to understand the push for married clergy, the Novus Ordo Missae, and many other aspects of the Vatican II era, we will find more illumination in dusting off the works of Martin Luther than in perusing the catalog of St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press [iii].

[i] See my article “New book opposed to priestly celibacy is riddled with errors” and part 3, “Clerical Celibacy,” of my lecture on the Amazon Synod.

[ii] Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion, ed. Holl, 367; translation in Cholij, Clerical Celibacy in East and West, 20. Cf. John Chrysostom, Homiliae in I Tim. Prol., PG 62, 503f, Hom. 2, in Tit. I, PG 62, 671; Eusebius of Caesarea, De Demonstratione Evangelica I, 9, GCS¸ 23, 43.

[iii] Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger recognized this widespread Catholic “revitalization” of Luther in his masterful paper “The Theology of the Liturgy,” given at the Journées liturgiques de Fontgombault, 22–24 July 2001, and republished in idem, Collected Works, vol. 11, Theology of the Liturgy (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2014), 541–57. Of course, since that time we have seen Pope Francis expressly honoring the memory and teaching of Luther.