Dr. Jeff Mirus is the Founder and President of CatholicCulture.org, one of the most popular Catholic websites on the Internet. CatholicCulture does a lot of good work for the Church, and we link to their articles frequently to buttress the points made in our own work.

Last week, however, Mirus wrote a perplexing article entitled, “The vernacular in, Latin out. Why?” In it, Mirus argues forcefully against the use of Latin in the liturgy:

I know that some Catholics remain very attached to Latin in the liturgy. The arguments in favor of it are easily summarized and a significant number of the Council fathers did make those arguments: In 1962, these arguments were as follows: First, Latin facilitated the universality of the Church because it enables every Catholic to worship in the same language; second, Latin had been used to good effect for a very long time, with the result that there was a great wealth of liturgical material in that language; third, the use of Latin made it easier to avoid certain dangers of change and experimentation which are congenial to the modern mind; fourth, the continued use of Latin in the liturgy would make it easier to maintain Latin as the official language of the Church.

There was merit in all of these points. However, it must be said that the first conveniently ignored other rites, traditions, and accommodations already in force in non-Western regions. Moreover, the third argument reflected a dominant fear of the pre-conciliar generation, the fear of running new risks (as I explained in Vibrant Catholicism, 1: Lamenting the entire 20th century). The great weakness of this attitude was its presumption that maintaining the status quo was not itself a grave risk—which was the whole point of Pope St. John XXIII in calling the Council. (Perhaps I should also mention that, as far as I can tell, no Council father made the argument, often heard later, that saying prayers in a language one did not understand created a more mysterious, reverent and transcendent atmosphere.)

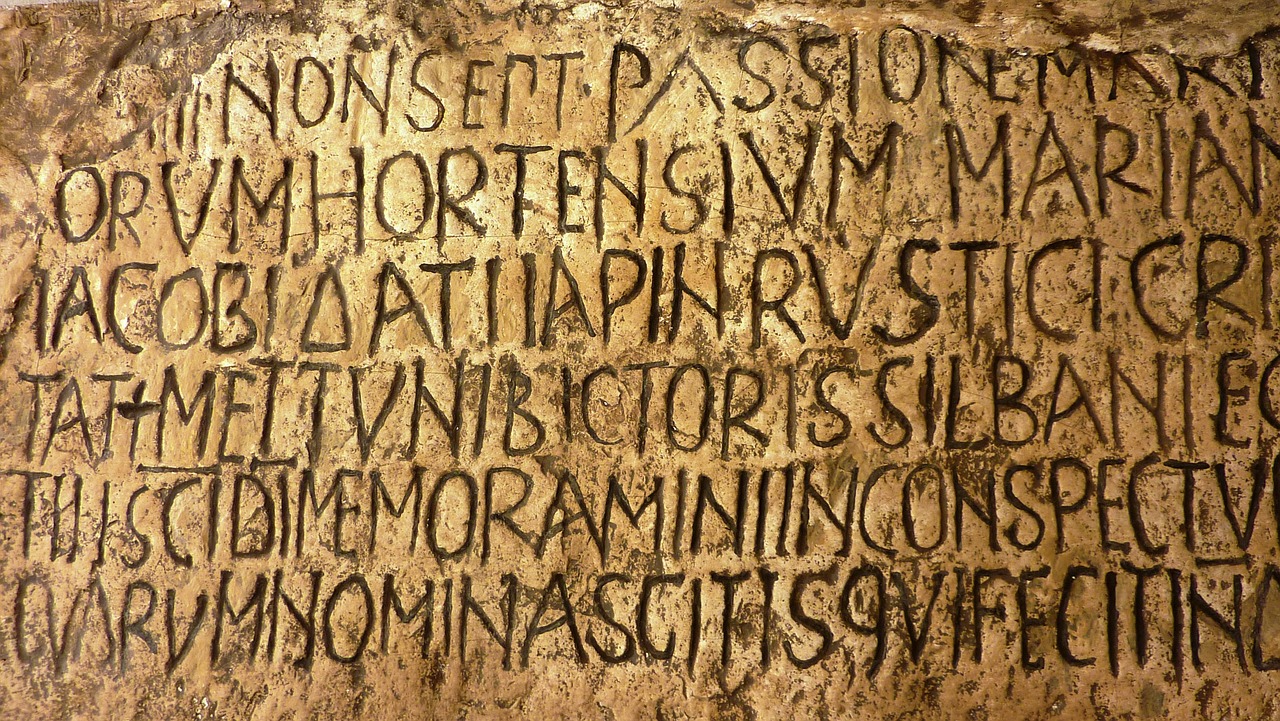

His re-statement of the arguments in favor of Latin may sound like just “points” or opinions, but they are in fact drawn, at least in part, from Magisterial teaching at the time. While the unfamiliar may think his mention of 1962 was in reference to the opening of the Second Vatican Council in October of that year, there was another event that happened in February, 1962 that has special significance to this topic: the publication of Pope St. John XXIII’s apostolic constitution, Veterum Sapientia.

It is important to note that an apostolic constitution is the most authoritative form of papal document. More than an an apostolic exhortation or letter, more than an encyclical, the apostolic constitution sits at the top of the hierarchy of magisterial texts, along with conciliar documents and decrees. In other words, apostolic constitutions are binding on the entire Church.

So what does Veterum Sapientia say about Latin? More than we can adequately summarize here. Suffice to say that Mirus’ objections were already considered by Pope St. John in this important papal document. With that in mind, I will attempt to break down Mirus’ arguments so that we can see the ways in which this text corresponds to (and precludes) his objections. I will present a paraphrase/summary of Mirus’ argument first (only using quotation marks when quoting him directly), a response from Veterum Sapientia next, and if necessary, my own comment beneath.

Mirus: The argument that Latin facilitates the Church’s universality through a unified language of worship ignores “other rites, traditions, and accommodations in force in non-Western regions.”

Veterum Sapientia:

Of its very nature Latin is most suitable for promoting every form of culture among peoples. It gives rise to no jealousies. It does not favor any one nation, but presents itself with equal impartiality to all and is equally acceptable to all.

[…]

Since “every Church must assemble round the Roman Church,” and since the Supreme Pontiffs have “true episcopal power, ordinary and immediate, over each and every Church and each and every Pastor, as well as over the faithful” of every rite and language, it seems particularly desirable that the instrument of mutual communication be uniform and universal, especially between the Apostolic See and the Churches which use the same Latin rite.

My Comment: It is important to note that Pope St. John was specifically instructing those Churches of the Latin rite. That is to say – the Roman Catholic Church. The Apostolic See has always made provisions for the other rites of the Church to retain their structure and language, as is evident in the liturgies of the Byzantine, Ukranian, Greek, Melkite, Ethiopian Coptic, and other Catholic rites.

Strangely, Mirus glosses over the second argument in favor of Latin — namely, that it “had been used to good effect for a very long time, with the result that there was a great wealth of liturgical material in that language”; but this is a point of serious significance, not just in the liturgy, but in the Deposit of faith as a Whole. As Veterum Sapientia states:

[T]he Latin language “can be called truly catholic.” It has been consecrated through constant use by the Apostolic See, the mother and teacher of all Churches, and must be esteemed “a treasure … of incomparable worth.” It is a general passport to the proper understanding of the Christian writers of antiquity and the documents of the Church’s teaching. It is also a most effective bond, binding the Church of today with that of the past and of the future in wonderful continuity.

Mirus: The argument that the use of Latin made it easier to avoid certain dangers of change and experimentation which are congenial to the modern mind “reflected a dominant fear of the pre-conciliar generation, the fear of running new risks … The great weakness of this attitude was its presumption that maintaining the status quo was not itself a grave risk…”

Veterum Sapientia:

Furthermore, the Church’s language must be not only universal but also immutable. Modern languages are liable to change, and no single one of them is superior to the others in authority. Thus if the truths of the Catholic Church were entrusted to an unspecified number of them, the meaning of these truths, varied as they are, would not be manifested to everyone with sufficient clarity and precision. There would, moreover, be no language which could serve as a common and constant norm by which to gauge the exact meaning of other renderings.

But Latin is indeed such a language. It is set and unchanging. it has long since ceased to be affected by those alterations in the meaning of words which are the normal result of daily, popular use. Certain Latin words, it is true, acquired new meanings as Christian teaching developed and needed to be explained and defended, but these new meanings have long since become accepted and firmly established.

My Comment: VS makes explicitly clear that the Church, “precisely because it embraces all nations and is destined to endure to the end of time … of its very nature requires a language which is universal, immutable, and non-vernacular.” Immutability is a key feature of the retention of Latin. If there was a “dominant fear” of “running new risks” as Mirus states, the half-century since the Council has shown it to be a well-founded one. Aggiornamento has been proven to be a spectacular failure, as every poll conducted on core Catholic belief, Mass attendance, and adherence to moral teaching attests.

But it is also worth noting that a great deal of the discord now reigning in the Church is because of an inability to communicate effectively across cultures. To give a perfect and commonplace example: think of the frequency with which Catholics are upset upon reading a report of some strange thing that Pope Francis has been alleged to have said, only to be later informed that the confusion was due to a translation error.

It was the Church’s ancient wisdom that official pronouncements were made first in Latin, so that discrepancies such as these were easily cleared up, so that idiom and colloquialism were unable to confuse translators, and precision of thought and speech would bring clarity, not misunderstanding.

Mirus then goes on, again, to ignore the fourth argument he re-states in favor of Latin: that “continued use of Latin in the liturgy would make it easier to maintain Latin as the official language of the Church.”

Again, VS contends that this is an important concern:

We also, impelled by the weightiest of reasons — the same as those which prompted Our Predecessors and provincial synods — are fully determined to restore this language to its position of honor, and to do all We can to promote its study and use. The employment of Latin has recently been contested in many quarters, and many are asking what the mind of the Apostolic See is in this matter. We have therefore decided to issue the timely directives contained in this document, so as to ensure that the ancient and uninterrupted use of Latin be maintained and, where necessary, restored.

[…]

In the exercise of their [the Bishops] paternal care they shall be on their guard lest anyone under their jurisdiction, eager for revolutionary changes, writes against the use of Latin in the teaching of the higher sacred studies or in the Liturgy, or through prejudice makes light of the Holy See’s will in this regard or interprets it falsely.

Mirus: Only the educated people in the West knew Latin, and that period of history had already come to an end. Latin was no longer the language of the people, or for that matter, of science, law, and medicine…

Veterum Sapientia:

It is a matter of regret that so many people, unaccountably dazzled by the marvelous progress of science, are taking it upon themselves to oust or restrict the study of Latin and other kindred subjects…. Yet, in spite of the urgent need for science, Our own view is that the very contrary policy should be followed. The greatest impression is made on the mind by those things which correspond more closely to man’s nature and dignity. And therefore the greatest zeal should be shown in the acquisition of whatever educates and ennobles the mind. Otherwise poor mortal creatures may well become like the machines they build — cold, hard, and devoid of love.

Mirus: The language of international diplomacy had moved away from Latin by the mid-to-late 20th century, and its retention in various areas of study after its time as the vernacular was favored only because of a “Euro-centric” world – a world which was no longer in focus.

Veterum Sapientia:

[T]he Catholic Church has a dignity far surpassing that of every merely human society, for it was founded by Christ the Lord. It is altogether fitting, therefore, that the language it uses should be noble, majestic, and non-vernacular.

Mirus: Even the educated men and women of the latter half of the 20th century were ignorant of Latin.

Veterum Sapientia:

There can be no doubt as to the formative and educational value either of the language of the Romans or of great literature generally. It is a most effective training for the pliant minds of youth. It exercises, matures and perfects the principal faculties of mind and spirit. It sharpens the wits and gives keenness of judgment. It helps the young mind to grasp things accurately and develop a true sense of values. It is also a means for teaching highly intelligent thought and speech.

[…]

Wherever the study of Latin has suffered partial eclipse through the assimilation of the academic program to that which obtains in State public schools, with the result that the instruction given is no longer so thorough and well-grounded as formerly, there the traditional method of teaching this language shall be completely restored. Such is Our will, and there should be no doubt in anyone’s mind about the necessity of keeping a strict watch over the course of studies followed by Church students; and that not only as regards the number and kinds of subjects they study, but also as regards the length of time devoted to the teaching of these subjects.

Mirus: Seminarians were also ignorant of Latin.

Veterum Sapientia:

Bishops and superiors-general of religious orders shall take pains to ensure that in their seminaries and in their schools where adolescents are trained for the priesthood, all shall studiously observe the Apostolic See’s decision in this matter and obey these Our prescriptions most carefully.

[…]

As is laid down in Canon Law (can. 1364) or commanded by Our Predecessors, before Church students begin their ecclesiastical studies proper they shall be given a sufficiently lengthy course of instruction in Latin by highly competent masters, following a method designed to teach them the language with the utmost accuracy. “And that too for this reason: lest later on, when they begin their major studies . . . they are unable by reason of their ignorance of the language to gain a full understanding of the doctrines or take part in those scholastic disputations which constitute so excellent an intellectual training for young men in the defense of the faith.”

We wish the same rule to apply to those whom God calls to the priesthood at a more advanced age, and whose classical studies have either been neglected or conducted too superficially. No one is to be admitted to the study of philosophy or theology except he be thoroughly grounded in this language and capable of using it.

[…]

In accordance with numerous previous instructions, the major sacred sciences shall be taught in Latin, which, as we know from many centuries of use, “must be considered most suitable for explaining with the utmost facility and clarity the most difficult and profound ideas and concepts.”

Mirus: Catholicism was experiencing growth in the third world — notably Africa and Asia — making Latin impractical since it did not form the basis for the languages of the people there.

Veterum Sapientia:

[T]he “knowledge and use of this language,” so intimately bound up with the Church’s life, “is important not so much on cultural or literary grounds, as for religious reasons.” These are the words of Our Predecessor Pius XI, who conducted a scientific inquiry into this whole subject, and indicated three qualities of the Latin language which harmonize to a remarkable degree with the Church’s nature. “For the Church, precisely because it embraces all nations and is destined to endure to the end of time … of its very nature requires a language which is universal, immutable, and non-vernacular.”

Mirus: Non-European members of the Curia were treated as outsiders. To that end, Latin had become “the language of ecclesiastical insiders—the language of the club.”

Veterum Sapientia:

[T]he Apostolic See has always been at pains to preserve Latin, deeming it worthy of being used in the exercise of her teaching authority “as the splendid vesture of her heavenly doctrine and sacred laws.” She further requires her sacred ministers to use it, for by so doing they are the better able, wherever they may be, to acquaint themselves with the mind of the Holy See on any matter, and communicate the more easily with Rome and with one another.

My Comment: This complaint requires further comment, since it steps outside the scope of Latin and into internal Church affairs. If Euro-centrism or other forms of elitism within the Curia are the problems, then deal with those problems. Latin has nothing to do with exclusionary practices, provided that prelates from across the world are educated in it, as they should be.

The Church, by its nature as a global, universal religion, requires a universal language to transcend nationalities and allow for communication amongst its prelates, clergy and theologians. If not Latin, then what? If Catholic constituencies of every nation are to communicate each in their own vernacular, this creates an obstacle to understanding where clarity and unity are of paramount importance.

Mirus: Latin affected all the Mass parts, not just the “Ordinary of the Mass” (the parts that always stay the same.) All of the Propers (the parts of the Mass that change) were also in Latin, as were the readings.

Veterum Sapientia (stated again as cited above):

In the exercise of their paternal care they shall be on their guard lest anyone under their jurisdiction, eager for revolutionary changes, writes against the use of Latin in the teaching of the higher sacred studies or in the Liturgy, or through prejudice makes light of the Holy See’s will in this regard or interprets it falsely.

My Comment: This is precisely the point of a universal liturgy for a universal Church. A Catholic of the Latin rite should be able to go to Mass in New York or Naples, Baton Rouge or Belgium, and experience the same liturgy. It is already a common practice during the Mass according to the 1962 Missal to offer the readings a second time in the vernacular preceding the homily, but the rest of the liturgy can (and should!) be easily followed in a hand missal. (I have written before about my own ignorance of Latin; it is no impediment in my attendance at the Traditional Latin Mass.)

Even Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Constitution on Sacred Liturgy from the Second Vatican Council, stated in no uncertain terms:

36. Particular law remaining in force, the use of the Latin language is to be preserved in the Latin rites.

In a more permissive section of the document, we read:

54. In Masses which are celebrated with the people, a suitable place may be allotted to their mother tongue. This is to apply in the first place to the readings and “the common prayer,” but also, as local conditions may warrant, to those parts which pertain to the people, according to the norm laid down in Art. 36 of this Constitution.

Nevertheless steps should be taken so that the faithful may also be able to say or to sing together in Latin those parts of the Ordinary of the Mass which pertain to them.

Latin was never meant to be removed from the liturgy. This is not what the Council Fathers agreed to.

The loss of the Church’s universal liturgical language represents part of a larger phenomenon that is creating a new scattering of Babel within our Faith. With the additional deconstruction of the rubrics of the Mass in the Novus Ordo, we also have lost the uniformity of sacred posture, gesture, and vesture. The diversification of language and action within the context of modern liturgy creates a disunifying experience for Catholics. Many of us have experienced this when traveling. Picking a Mass at random in a strange town can mean an experience that is either comfortable and familiar or (most often) almost completely alien, depending on the circumstances.

Mirus: In addition, the other sacraments and the Divine Office were prayed in Latin.

My Comment: This is a point that Veterum Sapientia does not directly address, and is one I partially agree with. I believe fervently in the superiority of the theology in the older sacramental forms — particularly baptism — and I think Latin plays a common role here to that offered in the Liturgy. On the other hand, the matter of the Divine Office may merit some consideration. I know some priests who, through their proficiency in Latin, can pray the office in that language with no ill effect — and it seems clear that such proficiency was willed by Pope St. John for all priests. Still, I have no particular objection to the praying of the breviary in the vernacular, provided that it is a faithful translation. I have an electronic copy of the 1962 Divine Office with Latin and English side-by-side. I find the presence of both informative, and when I have the opportunity to pray it, I switch back and forth between the languages, depending on my familiarity with each section.

In conclusion, while I understand the pragmatic reasoning behind the objection Mirus presents, I find that these not only fall short, but in fact contradict the provisions laid out by Pope John XXIII, who issued his constitution “in the full consciousness of Our Office and in virtue of Our authority” and who said “We will and command that all the decisions, decrees, proclamations and recommendations of this Our Constitution remain firmly established and ratified, notwithstanding anything to the contrary, however worthy of special note.”

In other words – this is what the Church believes about Latin as the language of the Church. Neither Dr. Mirus — nor the bishops he goes on to quote from to bolster his arguments — have the authority to change it.

The universality of the Church’s living language is of particular importance in the common prayer of the liturgy, the communication between clergy, and in the production of documents pertaining to the deposit and practice of the faith. And when so many of these arguments boil down to “People don’t know this stuff anymore,” or “it’s just too difficult,” they ring particularly hollow. Literacy has never been higher in the world. Access to modern printing techniques and digital content makes it possible to put resources in the hands of every Catholic to help them to understand — or at least follow along — with any sacrament offered in Latin.

Good Pope John didn’t seem particularly impressed with this sort of argument, either. When addressing professors of Theology and Philosophy, he wrote, “professors of these sciences in universities or seminaries are required to speak Latin and to make use of textbooks written in Latin. If ignorance of Latin makes it difficult for some to obey these instructions, they shall gradually be replaced by professors who are suited to this task. Any difficulties that may be advanced by students or professors must be overcome by the patient insistence of the bishops or religious superiors, and the good will of the professors.”

With respect to Dr. Mirus, vernacular comes and goes, but Latin will always be the living language of the Church.

UPDATE: Despite the still-binding nature of Veterum Sapientia, some will be tempted (erroneously) to write it off as a pre-conciliar document. I was reminded by a reader, however, that the current code of Canon Law also mandates that seminarians learn Latin:

Can. 249 The program of priestly formation is to provide that students not only are carefully taught their native language but also understand Latin well and have a suitable understanding of those foreign languages which seem necessary or useful for their formation or for the exercise of pastoral ministry.

There’s really no wiggle room on this.