Some people maintain that the Church cannot promulgate defective, useless, or harmful rites, citing Pope Pius VI’s Auctorem Fidei n. 78 and Pope Gregory XVI’s regional letter Quo Graviora n. 10. Those who wield these texts do not realize the trap into which they are falling.

Let us consider more closely what Pius VI condemned. The Italian regional Synod of Pistoia (1786), under the influence of Jansenism and Enlightenment rationalism, had argued that in the realm of Church discipline,

there is to be distinguished what is necessary or useful to retain the faithful in spirit, from that which is useless or too burdensome for the liberty of the sons of the New Covenant to endure, but more so, from that which is dangerous or harmful, namely, leading to superstition and materialism.

Note that this position enjoyed a second and more vigorous life among the liturgical reformers of the 1960s, who separated “what is necessary or useful to retain” from “that which is useless or too burdensome” (e.g., the fasting and abstinence enjoined by the missal prayers in Lent) and who waged an implacable campaign against things in the old liturgy they found “dangerous or harmful,” such as praying for the conversion of the Jews, proclaiming no salvation outside the Church, accepting the damnation of Judas and the threat of hell for the rest of us, putting forward the so-called legendary saints and their legendary miracles, manifesting a “preoccupation” with sin and an excessive emphasis on the world to come, encouraging the veneration of relics, and so forth.[1]

When Pius VI goes on to condemn the Pistoians—saying that their opinion

includes and submits to a prescribed examination even the discipline established and approved by the Church, as if the Church which is ruled by the Spirit of God could have established discipline which is not only useless and burdensome for Christian liberty to endure, but which is even dangerous and harmful and leading to superstition and materialism,—false, rash, scandalous, dangerous, offensive to pious ears, injurious to the Church and to the Spirit of God by whom it is guided, at least erroneous.

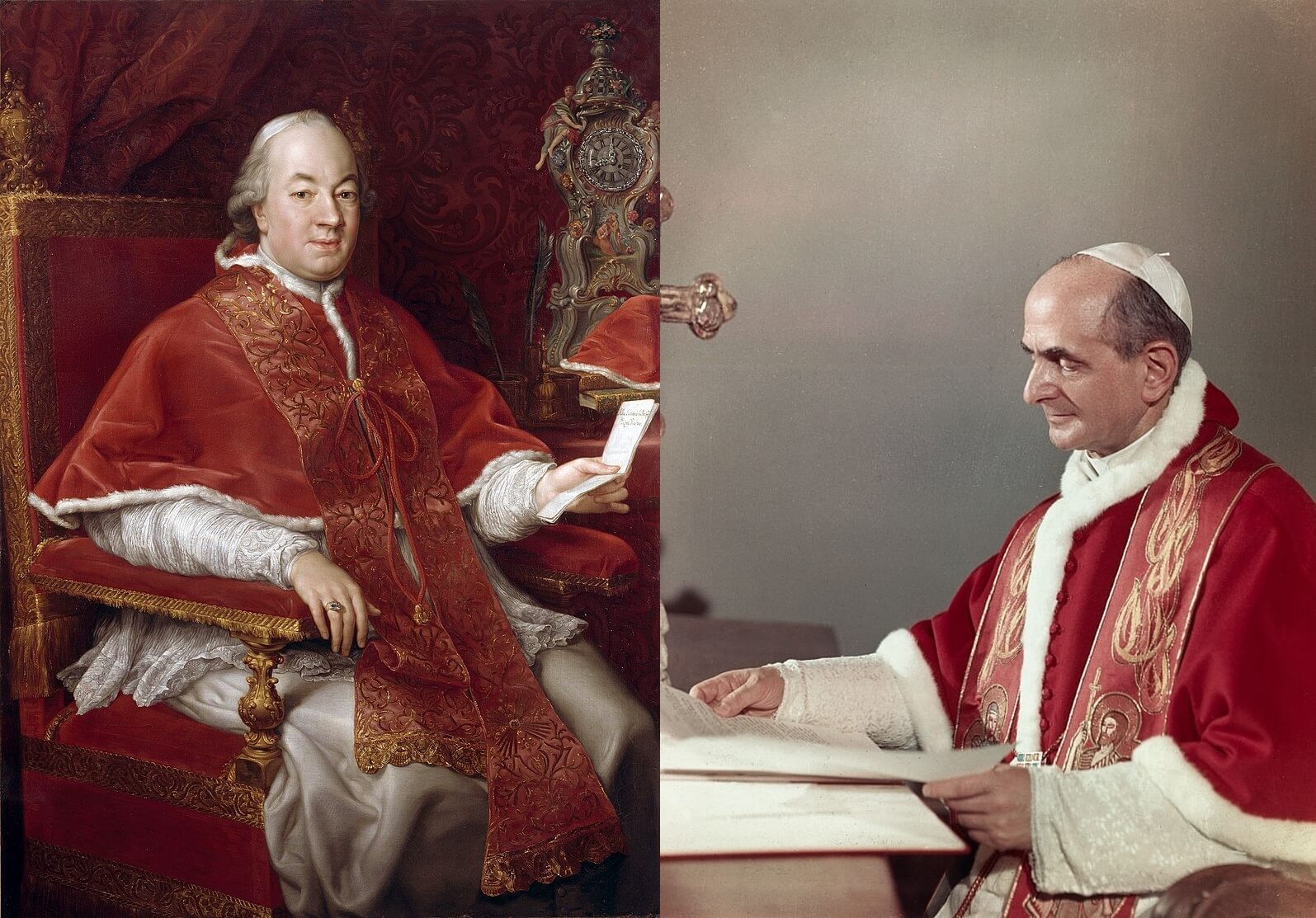

He is condemning in advance the reform of Bugnini, the Consilium, and Montini, which agree closely with the platform of Pistoia.[2] It would therefore be entirely illogical and self-contradictory to attempt to apply Auctorem Fidei of the year 1794, when the liturgy Pius VI was defending was none other than the Tridentine rite, to the Novus Ordo of 1969, which Paul VI intended as a replacement for the imperfect and no longer profitable rite of Pius V. Pius VI is appealing to the objective truth that the Church cannot err in approving her traditional liturgy; therefore in approving a non-traditional liturgy that departs from the uninterrupted chain of ecclesial transmission, it is Paul VI, not (e.g.) Archbishop Lefebvre, who runs afoul of his predecessor’s condemnation.

In Gregory XVI’s Quo Graviora, we see the same dynamic at work.[3] Written in 1833, not even forty years after Auctorem Fidei, the text makes it immediately clear that the pope is responding to the German cousins of the Pistoian heretics, whom he sees as moved by a “wicked passion for introducing novelties into the Church.” He describes their views:

They state categorically that there are many things in the discipline of the Church in the present day, in its government, and in the form of its external worship which are not suited to the character of our time. These things, they say, should be changed, as they are harmful for the growth and prosperity of the Catholic religion, before the teaching of faith and morals suffers any harm from it. Therefore, showing a zeal for religion and showing themselves as an example of piety, they force reforms, conceive of changes, and pretend to renew the Church.

Sounds strangely familiar, doesn’t it? This is precisely the rhetoric used by the central and northern European faction at the Second Vatican Council, as we find it carefully documented in Roberto de Mattei’s work (completing the documentation done by Ralph Wiltgen in The Rhine Flows into the Tiber).[4]

Continues Gregory: “They contend that the entire exterior form of the Church can be changed indiscriminately” and “the present discipline of the Church rests on failures, obscurities, and other inconveniences of this kind.” These sentiments, voiced relentlessly around the time of the last ecumenical Council, shaped the implementation of it, especially in the area of the sacred liturgy. “They attack this Holy See as if it were too persistent in outdated customs and did not look deeply inside the character of our time”—this was said in 1833, but it might as well have been 1963!

They accuse this See of becoming blind amid the light of new knowledge, and of hardly distinguishing those things which deal with the substance of religion from those which regard only the external form. They say that it feeds superstition, fosters abuses, and finally behaves as if it never looks after the interests of the Catholic Church in changing times…. Nor do We want to discuss their errors concerning the new Rituale written in the vernacular, which they want to have adapted more to the character of our times.

It’s both comical and tragic to see the parallels between the rebelliousness Gregory is condemning and the progressivist attitudes that prevailed at Vatican II, encouraged and rewarded by a sympathetic Paul VI. Yes, he was not as progressivist as some others were, and on certain issues he was capable of reaffirming traditional doctrine; nevertheless, the same can be said of the Pistoians and the Germans, who leaned Catholic on some points and Jansenist/Protestant on others.

Now we come to the important paragraph 10, in which I will highlight the lines that are lifted out of context and thrown in the faces of traditionalists:

These men [i.e., the self-styled reformers] want to utterly reform the holy institution of sacramental penance. They insolently slander the Church and falsely accuse it of error, and their shamelessness should be deplored even more. They claim that the Church, by ordering annual confession, allowing indulgences as an added condition of fulfilling confession, and permitting private Eucharist and daily works of piety, has weakened that salutary tradition[5] and subtracted from its power and efficacy. The Church is the pillar and foundation of truth—all of which truth is taught by the Holy Spirit. Should the church be able to order, yield to, or permit those things which tend toward the destruction of souls and the disgrace and detriment of the sacrament instituted by Christ? Those proponents of new ideas who are eager to foster true piety in the people should consider that, with the frequency of the sacraments diminished or entirely eliminated, religion slowly languishes and finally perishes.

As teachers remind their students again and again, context makes all the difference. Gregory defends the Church’s inability to go astray in the directing of the sacraments because the Church, as the pillar and foundation of truth, has always taught and acted consistently in regard to them. In other words, as with Pius VI, Gregory cannot conceive of a good Catholic who would “utterly reform” anything and thereby commit insolent slander against the Church by holding her to have erred in her long-standing discipline. Paul VI, on the contrary, held that the liturgy’s being in Latin was an obstacle to the salvation of souls: for him, this 1,600-year-old custom redounded to the “disgrace and detriment” of the sacraments.

Most ironically of all, the sacrament that was hit the hardest and suffered the most catastrophic decline in the Church after Vatican II was the “holy institution of sacramental penance.” The German radicals condemned by Gregory wanted to make penance more “meaningful” by freeing it from routine and obligation, something you did when and as you needed it; and Gregory predicted that the resulting decrease in confessions would eventually cause religion to languish and perish. That’s what comes of “proponents of new ideas who are eager to foster true piety in the people”—or, at any rate, what they think of as “true piety.” How many ideas in the 1960s were advanced under the banner of “freedom” and “maturity” and “a personal living faith” and so on? And how many millions of the faithful, with their new-found freedom and their assumption of worldly maturity, began to fall away? Without the institutional pattern and pressure they had no bearings any more, no support.

In short: Gregory XVI might as well be describing the liturgical and sacramental fallout of Vatican II, stemming from the same kind of false principles as the ones he diagnosed and condemned among certain Germans of his day. The same can be said of Pius VI with regard to the Italians of his day a few decades earlier. These popes are defending as the work of God and the rock-solid witness of the Church all the traditional liturgical rites that the would-be reformers of the Enlightenment era criticize as faulty and arrogantly propose to recast or renew. Either these popes are correct about the traditional rites of the Church, and the twentieth-century reformers are no better than their Pistoian and German forerunners; or the entire rationale of Auctorem Fidei and Quo Graviora falls apart. You can’t have it both ways.

Now I fully admit that Gregory XVI in Quo Graviora strongly reasserts the sole prerogative of the pope to make determinations about liturgy and sacraments. In the Tridentine perspective, wherein the Church must gather herself tightly together against errors and depredations from without, it makes sense that such grave decisions would be reserved to the Holy See, even if for much of Church history they were not. However, as before, Gregory asserts this authority because he sees the pope’s role as protecting and passing on what the Church already believes and does—not because he wants to turn things upside-down as the radicals wish to do. Put simply, the popes are not relativists who think anything goes as long as a pope signs off on it, or nominalists who think that if a pope says white is black, it’s black; nor are they voluntarists who think that if he declares X to be good, even if it’s bad, it will suddenly become good, or vice versa.

As someone on Facebook once put it: “The pope does not have the ontological power to decree tradition not-really-tradition, to decree an innovation more-or-less-tradition, to decree a destruction and invention a reform, or to decree an open, proclaimed, and lauded discontinuity a secret continuity. He can do things by force but he can’t make them not be what they are.” I’m with Aquinas on this one (against Ockham): not even God has the power to change the past or to violate the principle of non-contradiction.

God indeed protects the Church from promulgating invalid sacramental rites—no one seriously questions the validity of the Novus Ordo. But as Ratzinger himself noted again and again, the implementation of the Novus Ordo replaced organic development with “the model of technical production” stemming from ideas already condemned.[6] That is why he could say that the suppression of the Latin Mass “introduced a breach into the history of the liturgy whose consequences could only be tragic.”[7] These foreseen tragic consequences were the very reason Pius VI and Gregory XVI condemned what they did.

So the next time someone cites these papal documents or others like them against the traditionalist view, thinking he’s just won the debate, you may reply with a twinkle: “No, on the contrary, they support our view, and they undermine yours. What else would you expect from popes who wrote 175 years and 136 years prior to the advent of the New Mass? And if they could have lived to see it somehow, you can be sure they’d have condemned its architects a hundred times more fiercely than they did the presumptuous reformers of their day.”

Image credit: Getty.

[1] Some of these problems already appeared in liturgical reforms prior to the 1960s, but they did not dominate until the Consilium under Bugnini.

[2] In his overpriced but revealing book The Synod of Pistoia and Vatican II: Jansenism and the Struggle for Catholic Reform (2019), Shaun Blanchard candidly acknowledges (and celebrates) the parallels between that condemned council and Vatican II, including in the area of liturgical reform.

[3] This encyclical should not be confused with the better-known Quo Graviora of 1826, one of many papal encyclicals condemning Freemasonry.

[4] See Roberto de Mattei, The Second Vatican Council: An Unwritten Story (Loreto, 2012). I have noticed that very few conservatives or advocates of “ressourcement” who loudly defend Vatican II have actually bothered to study this painstakingly researched account by a master historian who demonstrates the domination of progressivist theology at the council. If only they would bother, it might temper their enthusiasm somewhat.

[5] As you might have guessed, the Pistoians and their German cousins held the error of antiquarianism: like the 20th-century liturgical reformers, they maintained that the liturgy of the Church had become corrupt and needed to be freed of its “accretions” and “restored” to a “more authentic” earlier form, which they curiously fashioned largely out of their own heads, as the Protestants had done before them, and with contempt for known elements of early liturgy that had survived in the traditional rites. This is why Pius XII made the same connection I am making when he warned that the liturgical movement right before Vatican II had been to some extent compromised by “the exaggerated and senseless antiquarianism to which the illegal Council of Pistoia gave rise” (Mediator Dei, 64).

[6] Johannes Bökmann, “Liturgiereform: Nicht Wiederbelebung sondern Verwüstung,” Theologisches 20.2 (February 1990): 103–4, quoting Ratzinger’s work in the book Simandron—Der Wachklopfer. Gedenkschrift für Klaus Gamber (1919-1989).

[7] Joseph Ratinzger, Milestones, trans. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 1998), 146-148.