July 17, 2019 saw the dedication of the new “Christ Cathedral” of the Diocese of Orange, California. An originally Protestant work of high modernist architecture repurposed on a staggering budget, the cathedral has understandably been the subject of animated discussion among its ardent proponents (such as Rev. Msgr. Arthur A. Holquin, who offers a guide to the cathedral here, and reflections on its dedication here) and its critics (such as architect Matthew Alderman and Duncan Stroik as early as 2012). My goal in this article is not to cover again ground that has already been covered, but to delve into aspects of the cathedral that raise serious questions about the vision that stands behind it.

We cannot conclude with certainty that what I am about to cover is fully intentional on the part of Christ Cathedral’s designers, regardless of anyone’s pointed assumptions. What is clear is that a choice was made to avoid normative Christian symbolism and to make use of signs associated with other religious traditions — elements that narrate a tale as shocking and scandalous as any report covering the abuse crisis.

But even if a cloaked message were not the objective of the artwork, the entire edifice remains a scandal, if for no other reason than the low quality of the work commissioned, the ugly manner in which holy persons are depicted, and the near comical awkwardness with which the mysteries of the Catholic Faith are proposed. It places a modernist caricature of the Faith before the eyes of those unfortunate enough to enter within it.

(N.B.: For many of the images in this article, a higher-res version may be viewed by clicking on the image.)

The Exterior

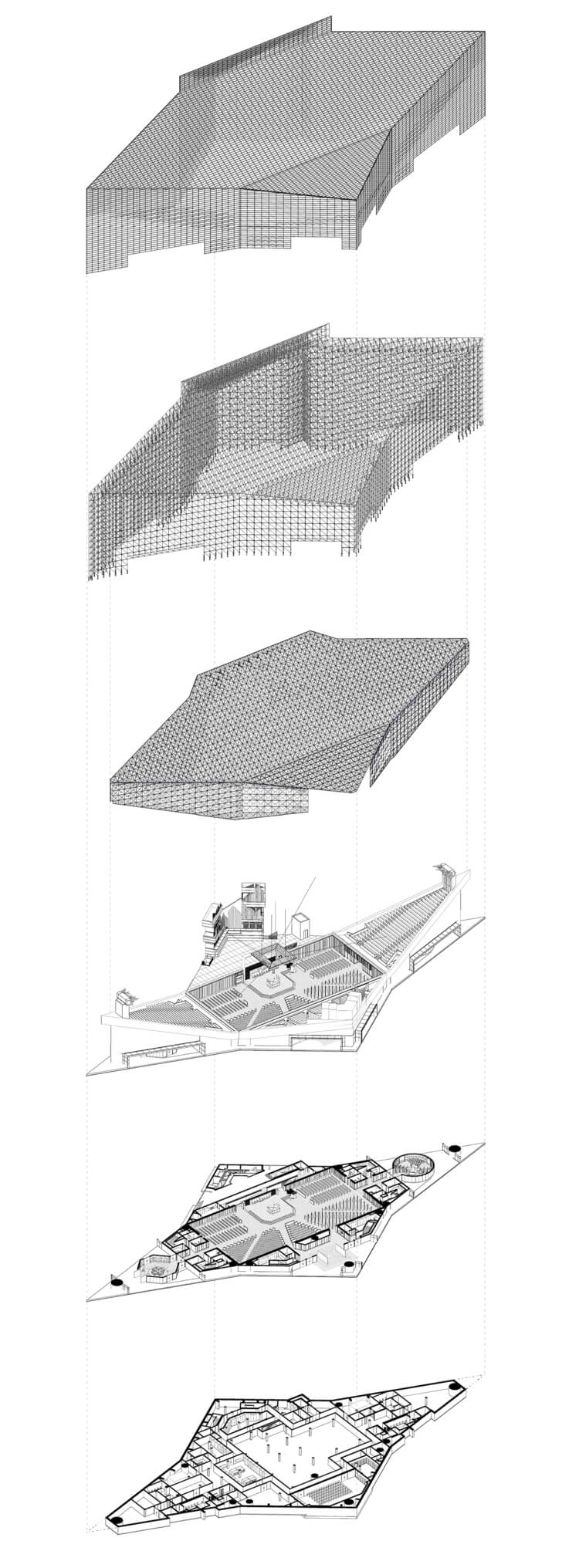

The exterior presents the spectacle of a glass electrified structure with no clear resemblance to a church and no apparent order within its design. It is a perfect “church of the Enlightenment” in that its primary characteristic seems to be illuminated formlessness — rationality for its own sake, the glory of immanence, without reference to tradition or transcendence: the Church of geometry and energy. We are reminded perhaps of a corporate headquarters for a telecommunications company. It is a church closed in on itself and not directional, a fortiori not cruciform.

The one gesture toward verticality is the tower, which, nevertheless, is more suggestive of science fiction than anything ecclesiastical. The building was never built to be a Catholic church, so the original builders cannot be blamed. Is it not odd, however, that once Catholics chose to purchase and inhabit this building and make it their own, not a single cross was permitted to mark the new cathedral or its tower for Christ?

The property itself, referred to as the “Campus,” is rife with the worship of personalities, architects, and brand names. A statue here or there intimates a general Christian “ownership” of the place, and a perceptible axis is indeed formed by the business tower and its reflecting pool. A separate structure from the church tower, this surprisingly named “Tower of Hope” is topped with a cross, which, to its credit as the only overt marker of Christianity on the Campus exterior, lights up at night.

Festal Doors

Before we analyze the artwork inside the cathedral, a subtle distinction must be made between iconography and iconology. Iconography is the description of symbolic forms depicted in a work of art. It is an analysis of symbols that derive from a readily recognizable, common currency of cultural or religious experience. Iconology synthesizes the wider meaning of a work of art by considering its underlying principles. This type of reading examines the symbol on more than face value, because principles are manifested by a composition in the context of its time, place, prevalent styles, and even influential personalities, for example. So, although we first recognize a symbolic form, viewing its placement in situ reveals more about the work than the work taken on its own.

The “festal” doors of the cathedral feature a large-scale bas relief of Creation, Adam and Eve, the Tree, and the Serpent across their immense horizontal width. This first encounter with the “symbols” of Christ Cathedral sets the stage for a tour of unease, tension, and even creepiness. The low ceiling stresses the main door’s crushing horizontality; it’s easy to feel that the building is squinting at you.

Reading left to right, the hands of (presumably) God the Creator emerge from the bottom, from the depths; notably, they do not descend from up above. We assume they are the hands of creation, only because what would appear to be the creation of Adam and Eve is next to them:

The two doors meet with a representation of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil — not an allegorical Tree of Life, as one would expect to find in a church. The Tree of Knowledge is a theme familiar in occultism, as per the Wiccan coin illustration. The doors show Satan wrapped around the trunk in the form of a snake:

As we scan to the right, we encounter more figures. And no figure on the doors looks alive. Their eyes seem closed. Nobody has either life or joy. Their existence is like that of programmed, gestureless automatons, or like the humans in deep sleep in The Matrix. At the far right we meet a winged creature who wears a helmet reminiscent of video-gaming. The helmet seems to possess horns, and a powerfully placed symbol extends from the ear:

The vignette seems to recall the sacrifice of Isaac, except both the ram and the child are blocked by the hyper-extended arm. Could this symbolize the abolition of all sacrifice? The “angel’s” gesture is similar to the hands of creation on the other side of the doors, an open palm posed with no artistic finesse. From a purely artistic standpoint, the arbitrary anatomy is a thing to wonder at. Muscles and sinews, proportion and texture aren’t a value here: is the “creator” in this cosmology a blind evolutionary god of glob?

While we cannot be sure what the earpiece is meant to symbolize, it has a close resemblance to solar and lunar symbols, some of which are employed by Wiccans and other occultists. Is this a stylized “triple moon” symbol of the self-styled “neopagans”? Again, it is the designer who has left these questions open, because he has not chosen to use clear, unequivocal Christian symbols. What are we to think? A quick Google search turns up many examples of the sort of pagan and occult symbols utilized here and throughout this cathedral:

To recap, there are no other symbols on the exterior of this building, and then the only decorated threshold in the whole church (inside or out) is a door that has you entering through an image of Satan, where creation starts from below, sin is the gateway to illumination (the doors are on axis with the main altar), and sacrifice — the “old way” — is abolished. In other words, the most important symbolic imagery of this building is a narrative that finds Lucifer and sin at its focal point. The specter of Teilhard de Chardin looms over every narrative the artwork evokes. Were we to use his doctrine as the key to unlock the meaning of these images, things would fall squarely into place.

Interacting with the symbolic composition and intentions behind these doors, the dilemma of believing your eyes versus “assuming the best intentions” begins to gnaw at the conscience. Were the designers here simply incompetent? Did they fumble a good-hearted intent by wanting to be too novel? Or did the designers of Christ Cathedral harbor contempt for the viewer by choosing to speak a language he cannot understand? Or is the designer actually saying what the viewer can reasonably deduce from the work? Who shall be the judge?

Vestibule Bas Relief

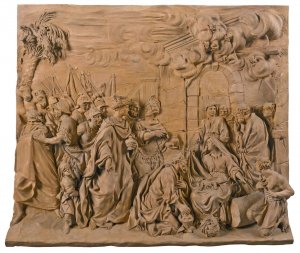

As mentioned, the festal doors are on axis with the main altar, but between them is a wall one is forced into immediately after entering the vestibule. On this wall is a second set of bas relief images. What is even more apparent in this bas relief, because of the many familiar figures depicted, is a refusal of the designers to commission figures that possess life, grace, and humanity. (Shown further below for contrast is a Nativity bas relief of Girolamo Ticciati [1671–1744].)

The Central figure is obviously a “Lamb” sitting upon the Book of the Seven Seals.

A sullen attack on sacred persons is the malformed depictions of the Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph. The Joseph figure is basically a Bible cartoon character, while the Mary figure is depicted with a ghoulish Adam’s apple on an impossibly long neck, supporting a tormented face. The halos are awkwardly slapped on, neither in perspective nor encompassing the head in a way familiar in Christian iconography. Eyes and their pupils don’t seem present.

Moreover, these two figures and the Lamb are the only figures to possess halos, and the Lamb is not depicted with a cruciform halo. Here, yet again, the guideposts that would allow us to read the bas relief as an explicitly Christian story are removed. Do we allow our mind to go where it is being led, or do we chasten ourselves into the hermeneutic of best intentions?

So much of the compositional value here is indeed clumsy, like the teetering banner, presumably of the resurrection, which seems to be sliding off the Lamb, or maybe attached with Velcro. Since awkwardness is a theme, can we simply call this attempt to conjoin the apocalyptic lamb to the Christ child of the Nativity “clumsy”? Or is this part of a greater modernist tale that tells us that biblical figures aren’t real? That figures like Mary and Joseph are convenient semi-mythological creatures? Was Christ not incarnate and born among us as a man? To place Joseph and Mary here answers no questions; it only creates them — and grave ones, at that. By way of iconography, it’s an awkward and often illegible mess. It reads as arbitrary (at best). By way of iconology, who can judge the wider meaning of these works of art, and by what rubric?

Unable to resolve the convergence point of palm fronds, the artist just slapped on a gob of clay and called it quits:

Hovering over the sparse palm fronds and the anemic background, we move to the left of the relief, reading toward the right, as we did the squinting festal doors.

Representing the “American experience,” or perhaps the “Orange Diocese experience,” is a procession that can best be described as a funeral cortège. One sees Saint John Capistrano (who was never in America, but to whom the Franciscans dedicated a mission today within the Orange Diocese), St. Lorenzo Ruiz of the Philippines, St. Junipero Serra conveniently looking guilty of his “crimes,” and St. Elisabeth Ann Seton:

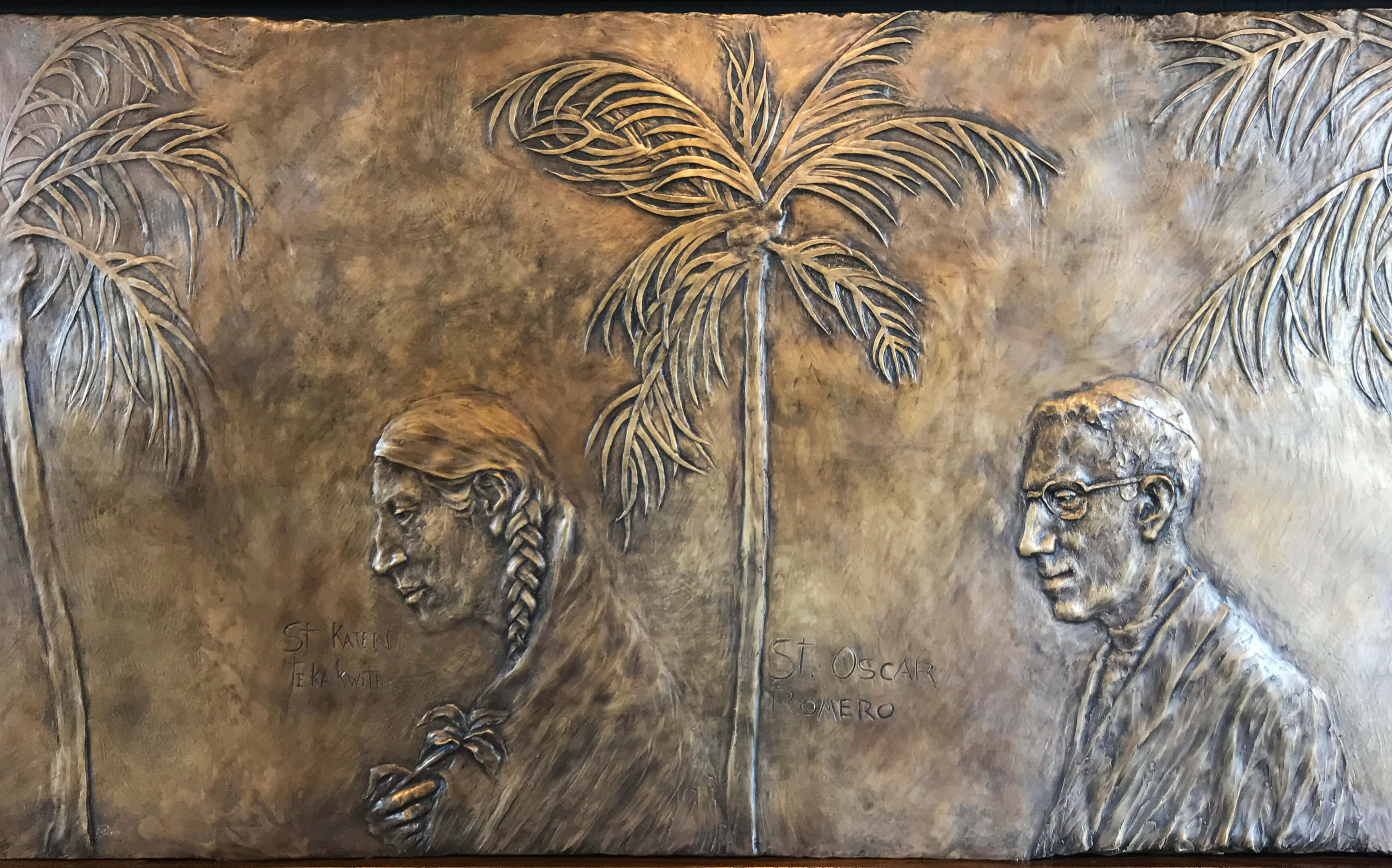

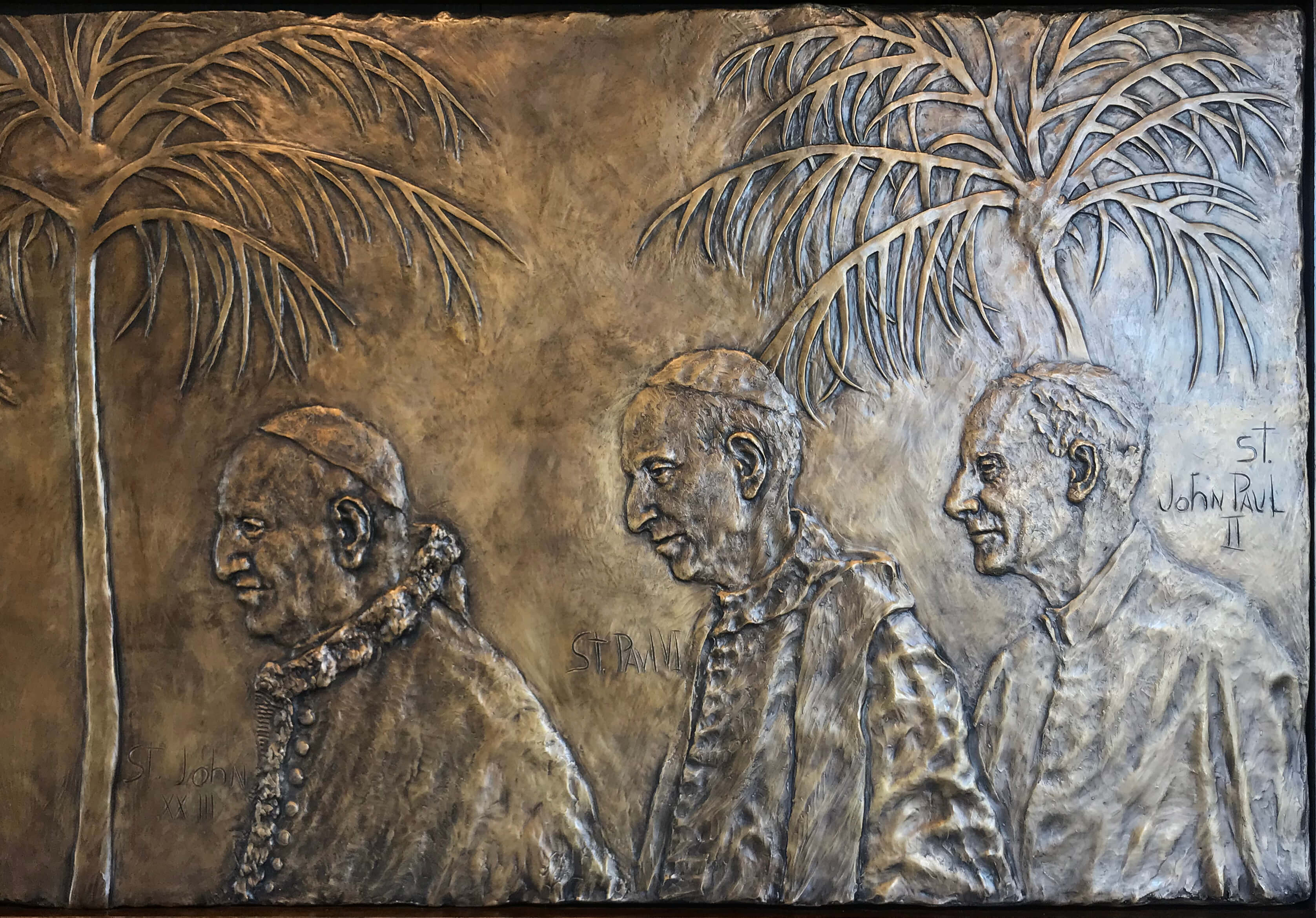

Passing over the Apocalypse-Resurrection–Nativity Lamb, the saints depicted to the right are Kateri Tekakwitha; Oscar Romero looking like a functionary; and the trinity of “conciliar popes”: John XXIII, Paul VI, and John Paul II, one progressively more bereft of papal garments than the other, as if shedding the prerogatives of their office. Is Vatican II where recognizable historical continuity ends and where “the Church” begins? If so, this New Church is modeling its temple for us, and we might say it is helpful to see it so clearly laid out.

The placement of the women at the front of each line, closest to the Lamb, as if eager for diaconal service, is surely not accidental.

The Interior

The interior presents a ceiling of soft glowing light, disorienting in its lack of focus and cool monotony. The overall effect is horizontal, spirit-crushing, and oddly foreboding.

But wait — there’s more.

The Altar

The location of the altar in the center of the room, the placement and type of presiders’ chairs, the dark torches on the ground punctuating the corners, the square mensa, and the all-seeing eye below the altar table at once bring us to a blood-curdling full stop. Can it be by accident that the altar at Christ Cathedral is a carbon copy of the altar of Freemasonry? Do we have a “reasonable hope” for denial? Even a cursory look at a Masonic altar makes the visual and symbolic link inescapable.

If one ignores the superior craftsmanship and style of the following Masonic temple, one can see the exact parallel in the disposition of the chairs — the tall chair in the center flanked by lower seating on either side — and then the square altar with the freestanding candles. (There is of course a fourth candle in the church, for it would have looked too strange to retain the asymmetry of three.)

It is here at the altar that we notice yet more symbols foreign to our Christian experience. Looking up at the crucifix, one perceives crescent moon shapes at the end of each beam. In the context of all we are experiencing, can we continue to claim ineptitude? Accident? Or just bad luck? Catholics simply have to ask, who approved these designs? Who came up with them? What reasons did they propose for their acceptance? What precedent for continuity did they provide?

Looking down, the altar platform is denied even the sense of solidity, as air return grills are prominently featured all over the top step, front and center.

Stations of the Cross

The Stations of the Cross are massive bronzes, also by the sculptor commissioned for the doors and the vestibule reliefs. Without getting into the questionable artistic value of these pieces, how comforting is an image of Our Lord with His blessed arms cut off?

Baptistry and Chrism Oils

Escaping the sunken “worship pit,” we walk through two short hallways on either side. The feeling is evocative of a medical office. We have the baptistry on one side and the Blessed Sacrament chapel on the other.

The baptistry is particularly ugly — “beam me up, Scotty!” With black metal doors that eerily evoke inverted crosses, white metal walls, and industrial grills for windows, in no way does this room feel like a place to be buried and raised with Christ. The walls are clad with perforated metal paneling, which ebbs and flows in a jagged attempt to suggest waves of water. The government-mandated bright green Exit signs seem to be written as imperatives rather than nominatives!

In the Baptistry, through a prison-like grid, we perceive a shelf and a display window facing outward. Here the chrism oils are located. Bewilderingly, they face outward in this vitrine — a sort of retail-like window exposed to the blazing California sun. The chrism is stored in enormous translucent glass jugs. Do they call them amphorae? The irreality of the place is a comic tragedy, with an accent on the tragedy.

Blessed Sacrament Chapel

In the “new theology” by which so much of Catholicism is denied implicitly or explicitly, we are told that “we see Christ when we see each other.” It’s a trope used to relegate the Blessed Sacrament and just about every devotion into the realm of “superstition” and “fetish.” Driving the point home, the Tabernacle is fashioned at eye level, on a pillar, in the middle of a circular room, without enjoying any elevation from the main floor, and with no physical distinction or threshold between the tabernacle and ourselves.

With the axis of the room inverted onto itself, the whole circle is an invitation to forget recollection and focus, or rather, never to learn what they mean in the first place. This is in keeping with the general exterior and interior design of the entire cathedral, which is polymorphous, acentric, and diffuse.

The tabernacle adds the distracting particularity of intentionally grotesque craftsmanship, which might prompt one to keep one’s eyes closed in avoidance rather than in meditation. The groom in the enamel depicting the wedding feast at Cana even sports a bow tie:

The story behind the tabernacle — sculpted by a German, Egino Weinert — is worth a listen, as narrated by Msgr. Holquin. Diocesan publications describe the work’s style as “simple, accessible, and almost child-like,” and that it certainly is. Why is nothing at Christ Cathedral serious when it matters most?

The web-footed candelabra, by the same German sculptor, are noteworthy:

Miscellaneous

One finds “raw” crystals all over the place, like in a Wiccan shop. One of the official explanations is that it’s a hat tip to the old “Crystal” Cathedral. Yes, adults said this. The crown over Christ’s head on the crucifix, the Pharaonic torches around the sharp-cornered altar, the paschal candle stand, all feature these prismatic crystals…

The dark reliquary beneath the altar top also features crystals, most notably what seems to be an all-seeing eye, fashioned from a crystal cabuchon:

Attempts have been made at splashes of color — with limited success, as we see in this “monumental tapestry”:

The cathedral’s confessionals are prone to more and more false abuse allegations by not segregating the penitent from the priest, in keeping with the sane practice of many centuries. One might say any advance in understanding and in return to sound tradition that has managed to occur in the postconciliar period, swimming against the tide of mediocrity and escapism, has been studiously neglected or patently contradicted in this shrine to futuristic nostalgia.

Broader Observations

Having touched on a few of many details that could be examined, it is time to make some broader observations.

Every plane in the building is truncated. No plane transitions into another naturally — the gray stone wainscot is truncated at the bottom and the top by a hard stop. Everything is angular, jagged, and sharp.

Most of the art is distinguished by its overtly poor quality (though not its cheap price tag) and brutalist or faux naïve design, which is antithetical to the worship of the God of beauty and order. It is no less antithetical to a religion established on traditio or the handing down of the Faith with its accumulated cultural inheritance and dense network of associations. The sacred figures are rendered in a “neo-primitive” manner, as if this were a sophisticated temple of tribal gods with no history.

In a reversal of the principle of incarnation, secular modernism, with its “view from nowhere,” has been allowed to govern church design, rather than church design shaping and influencing secular architecture, as occurred in the ages of faith and even for some time in the United States (examples here).

It may have seemed to the optimistic that Catholics possessing this enormous “iconic” property presented a noteworthy opportunity. Many options could have been envisioned — and many were offered — to make the Christ Cathedral project one that gave glory to God. But through the pride of some men, the blindness of others, and the greed of others still (including those who funded it to gain favor with institutions), we are now confronted with nothing less than a scandal — an eyesore and a counter-catechism.

One has to wonder why a building with so many and such massive limitations was ever considered worthy of housing Catholic worship, and in the process ate up $72 million (that we know of) from the pockets of the faithful. Certainly, California building costs are high, but by comparison, the magnificent Thomas Aquinas College chapel — also in California — was built for $23 million, less than one third of the cost of remodeling the Crystal Cathedral.

Christ Cathedral answers no questions. It only creates them — chief among them, “Could not these sums of money have been spent to feed the ‘poor in spirit’ with the kind of architectural and artistic beauty that nourishes the soul?”

There’s much ado about “prestige,” and much symbolism, and lots of narratives about “beauty” at the Christ Cathedral campus. Yet little about the project authentically says “Christian,” much less “Catholic,” or even “Catholic Christian” (a moniker Christ Cathedral liturgical consultant Br. William Woeger insists upon because, as he reminds us, “God is not Catholic”).

Sacred art is about answering questions, about explicating the Faith. It is and has always been a catechism in images. At Christ Cathedral, however, the big questions the art seems to answer are questions a Catholic should be embarrassed to ask: Are the symbols employed at Christ Cathedral intentionally subversive? Is it all just a case of more bad taste? Is there an agenda that uses the cover of “Catholic” to move itself along? Or is it just Catholics with no rudder, bad designers, and way too much money? Malice, stupidity, or incompetence?

The flourishing existence of occultism and other shadowy currents is prevalent news in our day. Popes have frequently warned of enemies of the Church who, not content to expend their fury against her in external attacks, have learned to pursue a more subtle and far more effective campaign of subversion within her very walls, by infiltrating seminaries, universities, chanceries, dicasteries, and episcopal conferences.

One can argue that other modernist monuments like the Oakland and Los Angeles cathedrals retain more dignity than Orange’s cathedral, because they avoided more explicit artistic expressions of alternative religion. Their architecture is something of an anti-gospel all the same, but bare walls and empty corners are more difficult to read than a bas relief — less immediately shocking, say, than a door whose opening is quite literally Satan.

While it’s difficult to identify exactly what group or tendency is operative in this situation, it seems that if we read the language of Christ Cathedral’s symbols in their context, we may well be standing in the midst of the world’s first anti-cathedral of the New Paradigm.