Fr. Dwight Longenecker is a fine writer. No one expresses a certain point of view better than he does. I’m not sure how to characterize it exactly; it might be described as a via-media-at-all-costs, the straight road that veers not off to left or right. He is determined to place himself between the extremes of the “trendies” and the “traddies” so that, in company with a remnant including at least George Weigel, he will emerge from this crisis not tarred and feathered as a progressive or bedecked with bays and rosemary as a traditionalist, but stolidly, if increasingly lonesomely, centrist.

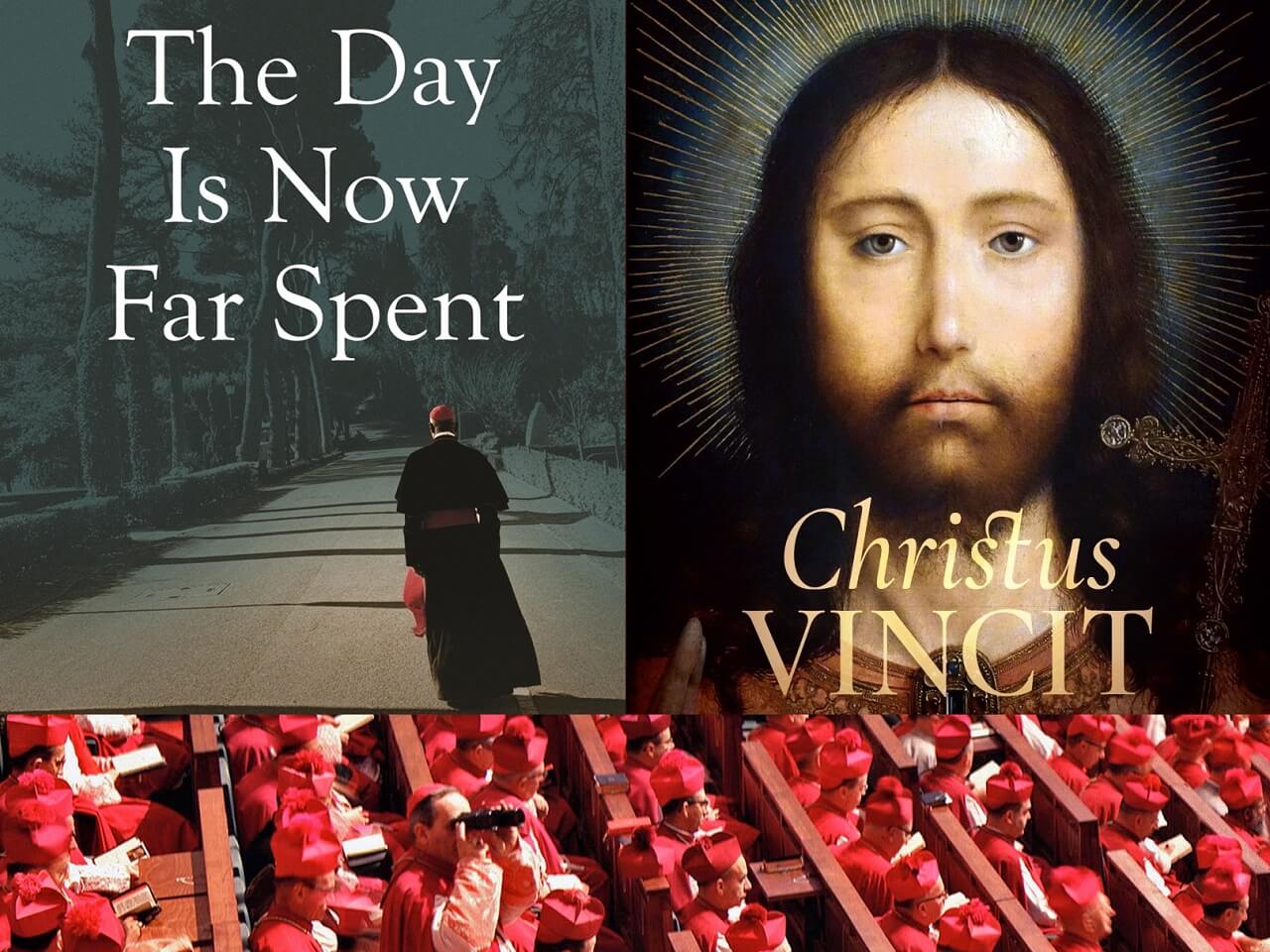

Such thoughts are prompted by an article of his entitled “What Shall We Do about Vatican II?” It’s true that it appeared a whopping three weeks ago, which means it belongs almost to another era, but it deserves our attention as a brilliant illustration of the aforementioned point of view. It takes the form of a paean to Cardinal Sarah’s latest book, The Day Is Now Far Spent. Bear with me, then, as I digress for a moment about this book.

As I know from my own copy, The Day Is Now Far Spent has a lot of good stuff in it. How could it not? Cardinal Sarah is a keen-sighted observer of the modern West, its accelerating apostasy and diabolical decomposition. He is a man who has a thing or two to say about the grave problems facing the Church.

What is very strange, however, is what Cardinal Sarah does not see — or is not willing to admit, either to himself or perhaps to his readership. For example, the dedication of his book reads, in part, as follows:

For Benedict XVI, peerless architect of the rebuilding of the Church.

For Francis, faithful and devoted son of Saint Ignatius.

A priest friend of mine, who like me is an admirer of Sarah’s previous books, God or Nothing and The Power of Silence, told me that when he saw this dedication, he wanted to chuck the book across the room. He summed up his reaction: “Benedict, the shepherd who fled for fear of the wolves? He’s the peerless architect of the Church’s rebuilding? That’s like saying a father who abandons his children to an abusive stepfather is the peerless architect of his family’s success. And Francis, a faithful and devoted son? Saint Ignatius must be rolling in his grave about the Jesuits — above all, this one, who says and does the opposite of everything Ignatius lived and died for.”

In a similar albeit milder vein, Jeff Mirus wrote in his withering review:

If the dilemma [of Catholics today] really does have Pope Francis at its center (and I do not see how any reasonable observer can doubt this), I have to say that the details of Cardinal Sarah’s solution are unworkable. For Cardinal Sarah always goes out of his way to indicate not only that he is not opposed to Pope Francis in any way but that in everything he writes he is echoing the Holy Father’s themes. Believe me, I get this; I understand why he chooses this path; but in the end, he pushes it too far and it just will not do.

It is true, of course, that Cardinal Sarah does not in any canonical or obediential sense “oppose the Pope” — a point which he makes with appalling sloppiness from time to time[.] … And it is true that Cardinal Sarah works hard at creating the illusion that he is following up lines of thought proposed by Pope Francis himself. … But in fact, the grand alliance of what we might call “The Friends of Pope Francis” constantly tries to bring against Cardinal Sarah this charge of opposition to the Pope, precisely because it is so obvious that Sarah’s constant recommendations are seriously at odds with much of what Pope Francis says.

What is clear to everyone in this is that Cardinal Sarah has tried mightily to find a few good quotes from Pope Francis — and, after all, there are many to be found if a student can survive the avalanche of intellectual and spiritual confusion long enough to dig them out — so that he can maintain the fictional aspect of his method throughout the book.

I am reminded of an ad I saw recently for The Augustine Institute, in which a course on moral theology was named “Who am I to judge?,” and — cleverly? — Pope Francis was trotted out with a quotation opposed to relativism. As if to say…as if to say what, exactly? That he’s really and truly on our side, on the side of Catholic tradition, Catholic theology, Catholic life? Stringing up those good quotes like so many blinking Christmas lights will not chase away the cavernous darkness.

Fr. Longenecker praises Cardinal Sarah for following and testifying to the via media between the trendies who got drunk off of the spirits of Vatican II and the teetotaling traddies who will not touch the stuff. The viamedians will locate, with determination, the (more or less) traditional-sounding quotes from Vatican II and say: “See? I told you so. It’s not all bad! Now we can forget our troubles with a big bowl of ice cream.” It’s important, in any case, not to look too closely into the history of the Council and the shaping of its documents; the manifold lines of influence connecting nouvelle théologie and ressourcement with Modernism; the way Paul VI and his episcopal and curial appointments adopted a line that conflicted with Catholic beliefs and instincts on point after point; and above all, the final stages of the liturgical reform (ca. 1963–1974), which, in its artisanal blend of faux ancient, quasi-Eastern, and de novo sources, “active participation,” options galore, vernacular, and new music, resembles nothing Roman or Catholic from all the centuries of the Church’s history and enjoys validity in a vacuum. Those who broach such issues are not engaged in a serious way, but are written off as “radical Catholic reactionaries” whom everyone should be strong-armed — or Armstronged? — to avoid like the plague. I suppose that’s one way to deal with uncomfortable truths, but it’s not recommended for those seeking the real causes of today’s crisis.

Like George Weigel, who recently pontificated that “nostalgia for an imaginary past is not a reliable guide to the future,” Fr. Longenecker expresses his concern about those who “do” beautiful Tridentine liturgies: “If one is not careful it all becomes no more than an exercise in nostalgia and no more authentic than Cinderella’s castle at Disneyland.”

I wish someone would explain to the Longeneckers and Weigels of the world that whatever else is going on, nostalgia plays no role in it. Most of the people in a modern TLM congregation were born well after Vatican II and have not the slightest clue what things were like beforehand, nor do they particularly care. They are not hankering for a lost culture or seeking to reconstruct a lost world. Rather, they desire a proper Catholic culture here and now, which begins with the solemn, formal, objective, beautiful divine cult we call the sacred liturgy, which we do inherit from many centuries of faith — but we live it and we love it now. Moreover, the elderly who join us for the TLM are well aware that much of what we are doing after Summorum Pontificum is better than what they saw as children — and they are grateful for it. Generally speaking, the Low Masses are more reverently recited; the High Masses, even Solemn High Masses, are more frequent, better attended, and more beautiful; indeed, a Pontifical Mass may come soon to a city near you.

The phenomenon of nostalgia is found, rather, among those who wish they could recover the glory days of John Paul II, when it seemed the Church was riding high — as if we might, just might, recover from the postconciliar tailspin; among Boomers, for whom Marty Haugen’s music “hath charms to soothe a savage breast, to soften rocks, or bend a knotted oak”; among elderly churchmen who long for the halcyon days of Vatican II. Trads are clear-sighted, energetic, and future-looking people. They are too busy discerning vocations, managing a pewful of children, singing in chant scholas, or cooking for potlucks after Rorate Masses to have time for lollygagging in the lanes of an inaccessible memory. It’s the ones hugging their Breaking Bread hymnals or their “JP II We Love You” teddy bears who are the misty-eyed sentimentalists.

Along these lines, Fr. Longenecker still believes in the “hermeneutic of continuity” between the premodern Church and the Church of Vatican II. This hermeneutic died when Pope Benedict resigned. That act of abandoning the flock to the wolves symbolized the practical and theoretical abandonment of this vision of harmony (“if only we could just read what the 16 documents actually say!”) and its replacement by the more sober realization that the Council chose accommodation to the mind and modes of modernity over clear continuity with tradition. We are now reaping the rotten fruits of that choice.

We can see, moreover, the full magnitude of the evils that remained in the Church in spite of, and at times because of, John Paul II and Benedict XVI, who, with all their indubitably great qualities, spent too much time globetrotting, professorializing, and praying for peace with non-Catholics and too little time mucking out the stables, replenishing the hired hands, and rebuilding the fallen structures of the Church. Were it not for their misplaced priorities, we would not be suffering under the twin burdens of an entrenched clerico-homosexual culture and a rigid adherence to soft modernism at all levels and in all areas.

At one point Fr. Longenecker says, concerning the Council’s “opening to the world” and “a spirituality for all with open doors to all”: “I am grateful for the spirit of openness, but also grateful for the spirit of resourcement [sic] — going back to the roots.”

Leaving aside the question of whether it’s the business of the Church to open herself to the world — since, even after the Incarnation, death, and resurrection of Christ, His three favored apostles Peter, James, and John still take pains to tell us that once we have “escaped from the corruption that is in that world” (2 Pt 1:4), we should “love not the world, nor the things which are in the world” (1 Jn. 2:15), since “whosoever will be a friend of this world becometh an enemy of God” (Jas. 4:4), all of which St. Paul pithily endorses: “be not conformed to this world” (Rom. 12:2) — we may want to examine more honestly the idea that Vatican II sought to reconnect us with our heritage, our “sources.” This claim is more than questionable; it is Big Baloney.

If the churchmen in charge had been really interested in ressourcement or returning to the roots, they would have preserved our traditional liturgy, which connects us to the Church of every age, instead of inventing a hybrid antiquarian-ultramodern liturgy for Modern Man. The architects of the Council, who, lucky for us, wrote and spoke freely about their intentions, were trying rather to domesticate the Modernism of the 19th and early 20th centuries, to make it mainstream and acceptable — the “Trojan Horse” about which Dietrich von Hildebrand perceptively spoke. It was above all the philosophers and sociologists who saw the magnitude of the change, because they are accustomed to thinking carefully about phenomena, causality, patterns, and movements.

Fr. Longenecker may well be right that Vatican II “brought him into the Church.” But God can and frequently does write straight with crooked lines. He awakened my love for church music in a parish covered with carpet and extraordinary ministers. He brought me to a more serious faith through the charismatic renewal and later by the Novus Ordo in Latin, which are classic way stations: as with a first girlfriend, or a first job out of college, it’s not the place one usually ends up. One’s faith matures; one sees that what used to satisfy begins to look shallow, brittle, awkward, forced. The Lord led me beyond these way stations into full-blooded Catholic thought, culture, and worship. “Loyalty to tradition, love of traditional liturgy and devotions, and the depth of traditional Catholic spirituality” — in Fr. Longenecker’s eloquent words — are not particularly characteristic of Vatican II or any phase of its implementation. Those who want to find them and keep them are going to need to look elsewhere.

As a historical event, Vatican II is receding farther and farther into the past — and into irrelevance. I recall one author writing some years ago in First Things that for his students in the college classroom, “Vatican II” evoked neither more nor less than “Chalcedon” or “Ephesus.” All had to be chiseled equally into the blank slates, not to say blank stares.

In terms of its theological or spiritual contributions, whether in de fide definitions and anathemas or in the unleashing of edifying energies, Vatican II is looking more and more like the most fussed over and the most negligible council in the history of the Church. If it disappeared into thin air, what of lasting value would we actually lose? The vocation of the laity? That was already there in Leo XIII’s Sapientiae Christianae. The duties of priests and bishops? The Fathers of the Church and earlier popes had wisely discoursed on these matters. How the Catholic Church relates to other Christian bodies and non-Christian religions, or proper Church-State relations? Talk about cans of worms… The way to worship God in spirit and in truth? Please.

When we consider the sheer magnitude of positive, constructive, tradition-guarding reform inaugurated and guided for centuries by the Council of Trent, we are justified in concluding that Vatican II, in stark contrast, was a monumental failure. Church councils of the past always sought to bring clarity to debated questions, refine the expression of doctrine, bear witness to the fullness of the Faith, and fearlessly condemn errors. In doing these things, they were truly pastoral. The Councils did not indulge in ambiguity, sow obscurity, backtrack, sidestep, refrain from condemnation due to a sentimental caricature of mercy, or enthrone a nebulous pastorality as the primary concern. This is why Vatican II is the great exception and the great dead end. The Council Is Now Far Spent.

Fr. Longenecker concludes his article by saying Cardinal Sarah “has the final word.” If that is true, we are sorry folks, indeed, for he is merely repeating the same stale advice that conservatives have been giving ineffectually and unsuccessfully for fifty years: “Just read the documents more carefully and you will see…” As a matter of fact, Bishop Schneider is reading the Council carefully, and that is why he sees the serious flaws in it. Bishop Schneider’s book-length interview Christus Vincit: Christ’s Triumph over the Darkness of the Age, which appeared at about the same time as the cardinal’s, takes all prizes — in its moving personal stories, in its remarkable range of topics, in its depth and clarity of argumentation, in its honest grappling with our situation. Bishop Schneider, a far more reliable and realistic guide than Cardinal Sarah, is not afraid to point out serious weaknesses in the Council’s very texts, and in the way these texts have been wielded.

To Fr. Longenecker’s question, then — “What shall we do about Vatican II?” — I suggest we leave it alone, leave it behind, leave it in peace, along with Lyons I, Lateran V, and other councils you’ve never heard of, and turn our minds and hands to better things ahead: reaffirming and rekindling the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Faith that predated it and, by God’s grace, still endures five decades later, for neither it nor its liturgical expression, neither the lex credendi nor the lex orandi, can be altogether obliterated off the face of the Earth.

If I might change the conversation, I would say a more pressing question is: “What shall we do about Vatican I?” This past Sunday, December 8, marked the 150th anniversary of the opening of a council that would forever change the way Catholics perceived and interacted with the papacy — the impetus for a runaway hyperpapalism capable of leveling centuries of tradition. In many ways, we are more threatened today by the spirit of Vatican I, which it will take a mighty exorcism to drive away.