One of the most remarkable episodes in the life of Karol Wojtyła—and one from which we can learn a great deal today—took place during his time as Cardinal of Kraków. It is astonishing to me that, with all the attention lavished on John Paul II, this incident has failed to attract notice, much less commentary. The same is true of a momentous event in the life of the great Cardinal Josef Slipyj.

Clandestine Priestly Ordinations

For readers who may be unfamiliar with it, Ostpolitik refers to the Vatican’s Cold War strategy of conceding certain demands of the Communists in Eastern Europe in return for supposed tolerance of an ongoing minimal ecclesial existence. Weigel himself has been a candidly severe critic of Ostpolitik, a theme to which he returned only two weeks ago in an article on its architect, Cardinal Agostino Casaroli.[1] Weigel’s authoritative biography Witness to Hope presents the salient facts accurately, albeit with a bit of sugar-coating:

Cardinal Wojtyła never doubted the good intentions of Paul VI in his Ostpolitik, and he certainly knew of the Pope’s personal torment, torn between his heart’s instinct to defend the persecuted Church and his mind’s judgment that he had to pursue the policy of salvare il salvabile [“to save what could be salvaged”]—which, as he once put it to Archbishop Casaroli, wasn’t a “policy of glory.” The archbishop of Kraków also believed he had an obligation to maintain solidarity with a persecuted and deeply wounded neighbor, the Church in Czechoslovakia, where the situation had deteriorated during the years of the new Vatican Ostpolitik.

So Cardinal Wojtyła and one of his auxiliary bishops, Juliusz Groblicki, clandestinely ordained priests for service in Czechoslovakia, in spite of (or perhaps because of) the fact that the Holy See had forbidden underground bishops in that country to perform such ordinations. The clandestine ordinations in Kraków were always conducted with the explicit permission of the candidate’s superior—his bishop or, in the case of members of religious orders, his provincial. Security systems had to be devised. In the case of the Salesian Fathers, a torn-card system was used. The certificate authorizing the ordination was torn in half. The candidate, who had to be smuggled across the border, brought one half with him to Kraków, while the other half was sent by underground courier to the Salesian superior in Kraków. The two halves were then matched, and the ordination could proceed in the archbishop’s chapel at Franciszkańska, 3.

Cardinal Wojtyła did not inform the Holy See of these ordinations. He did not regard them as acts in defiance of Vatican policy, but as a duty to suffering fellow believers. And he presumably did not wish to raise an issue that could not be resolved without pain on all sides. He may also have believed that the Holy See and the Pope knew that such things were going on in Kraków, trusted his judgment and discretion, and may have welcomed a kind of safety valve in what was becoming an increasingly desperate situation.[2]

Notice how Weigel tries to side-step the significance of the facts he has presented. In the midst of a mid-century Church held in the grip of an unquestioned ultramontanism, Cardinal Wojtyła simply defied the papal interdict on such ordinations and proceeded nonetheless, with the involvement of an auxiliary bishop and with the knowledge of the superiors in question. The phrase “in spite of (or perhaps because of)” is a remarkable piece of gobbledygook; how could it make sense to say that someone went ahead with forbidden ordinations because they were forbidden? Again, if a Cardinal who knew he was acting against the will and law of the pope did not inform the pope, can one truthfully say “he did not regard them as acts of defiance of Vatican policy,” when that is precisely what they were?[3] Obviously he did not raise the matter with “the authorities” because he believed they were in the wrong in this case. Moreover it is purely gratuitous to assert, in a sanitizing effort, that Wojtyła “may also have believed that the Holy See and the Pope knew that such things were going on in Kraków.” Where is the evidence for this? It was because the Pope and his Secretary of State at the time did not trust the judgment and discretion of such heroes and confessors of the Faith as Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński or (as we shall see below) Cardinal Josyf Slipyj that the Vatican had forbidden ordinations, whether above ground or underground. Weigel should just stick to the truth: as he rightly says, the Cardinal knew he had an obligation in the sight of God, and a duty to suffering fellow believers. That is all that needs to be said.[4]

According to another biographer of Karol Wojtyła:

Wojtyla had a greater connection to the Prague Spring than he could let on. Over the years, he had gradually expanded his secret ordination of underground Czech priests. By 1965 he was also training and ordaining covert priest candidates from Communist Ukraine, Lithuania, and Belarus, where seminaries had also been closed. Some candidates sneaked across the border to Poland, while others arranged for secular jobs that allowed them to travel legally; for example, one was a psychologist who regularly visited a Polish health institute. Wyszynski, in Warsaw, was aware of the nature, if not the details, of these activities. Had authorities known of them, they might well have jailed Wojtyla.[5]

Whether or not we are among those who laud “John Paul the Great,” one thing is clear: what he did in Kraków was entirely justified, and adds to, rather than detracts from, the luster of his character.

Clandestine Episcopal Ordinations

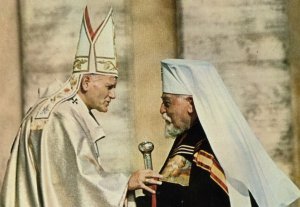

Next we should have a look at the parallel case of Cardinal Josyf Slipyj (1892–1984), whose cause for canonization has been introduced in Rome. He one-upped Wojtyła by performing forbidden clandestine episcopal ordinations because of his inner conviction that the good of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC) in the Soviet Union required it. As Fr. Raymond J. De Souza summarizes:

In 1976, the head of the UGCC, Cardinal Josef Slipyj, living in exile in Rome after 18 years in the Soviet gulag, feared for the future of the UGCC. Would it have bishops to lead it, given that Slipyj himself was now over 80? So he ordained three bishops clandestinely, without the permission of the Holy Father, Blessed Paul VI. At the time, the Holy See followed a policy of non-assertiveness regarding the communist bloc; Paul VI would not give permission for the new bishops for fear of upsetting the Soviets. The consecration of bishops without a papal mandate is a very grave canonical crime, for which the penalty is excommunication. Blessed Paul VI—who likely knew, unofficially, what Slipyj had done—did not administer any penalties.[6]

I was recently discussing this matter with a knowledgeable source who had read the Memoirs of Cardinal Slipyj, which are not yet available in English. He told me that the Cardinal was lured to Rome under the pretext of “having a meeting” and was then told he could not leave Rome to return to the Soviet Union to live among and suffer with his people, even though he was quite willing to go back to the Gulag. It was a source of great suffering to him to be living in comfort in Rome while his flock labored under Communist and Eastern Orthodox oppression. As Jaroslav Pelikan writes in Confessor Between East and West:

Here in exile, here in the Rome for which he and his church had sacrificed so much, the Ukrainian metropolitan felt increasingly hemmed in by what he called, in one of the subtitles of a document submitted to the pope, the “negative attitude” he continued to encounter from “the sacred congregations of the Roman curia.” Sometimes, in his exasperation at that attitude, he would even resort to the hyperbole of declaring that he had never experienced such mistreatment from the atheists in the Soviet Union as he was experiencing now from fellow Catholics and fellow clergy in Rome.[7]

According to my aforementioned source, Paul VI certainly knew of the secret episcopal ordinations but declined to punish the Cardinal because he was widely revered as a Confessor of the Faith. One of the bishops secretly ordained was Lubomyr Husar; John Paul II later officially recognized his consecration, appointed him Major Archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, and created him a cardinal in 2001.[8]

It also bears noting that Cardinal Slipyj’s action took place at a time when the Pio-Benedictine Code of Canon Law (1917) was still in force. Can. 2370 of the 1917 Code reads: “Episcopus aliquem consecrans in Episcopum, Episcopi vel, loco Episcoporum, presbyteri assistentes, et qui consecrationem recipit sine apostolico mandato contra praescriptum can. 953, ipso iure suspensi sunt, donec Sedes Apostolica eos dispensaverit” (A bishop who consecrates someone as a bishop; bishops who are present [when this happens], or assisting priests who take the place of bishops; and a person who receives consecration without apostolic mandate, contrary to what is prescribed in canon 953, are suspended by virtue of the law itself, until the Apostolic See dispenses them). The language of the Code makes it clear that such clergy are suspended not in virtue of an announcement of the penalty but simply on account of what they have done, namely, to consecrate without an apostolic mandate—something Paul VI never granted to Slipyj. A legal positivist would say that the suspension he incurred would have had to be expressly removed later on. Yet the fact that the suspension was never lifted is an eloquent testimony to the role of epikeia in interpreting and applying law. In short: a situation existed in which the canon simply did not take effect. This ought to give us pause about the limits of legal positivism.

A New Lens for Viewing Écône

When the Church is under attack and her survival is at stake, or when her common good is gravely threatened, flagrant “disobedience” to papal commands or laws can be justified—indeed, not only justified, but right, meritorious, the stuff of sanctity. No one has ever questioned that rules concerning episcopal consecrations are the pope’s right to establish, and that Wojtyła and Slipyj unquestionably and knowingly violated ecclesiastical law, which should have merited them a place of opprobrium alongside Archbishop Lefebvre. Instead, we celebrate them as heroes of the resistance against Communism.

The reason we do so is that we recognize a more fundamental law than that of canonical dictates: salus animarum suprema lex, the salvation of souls is the supreme law. It is for the salvation of souls that the entire structure of ecclesiastical law exists; it has no other purpose than ultimately to protect and advance the sharing of the life of Christ with mankind. In normal circumstances, ecclesiastical laws create a structure within which the Church’s mission may unfold in an orderly and peaceful way. But there can be situations of anarchy or breakdown, corruption or apostasy, where the ordinary structures become impediments to, not facilitators of, the Church’s mission. In these cases, the voice of conscience dictates that one do what needs to be done, in prudence and charity, for the achievement of the sovereign law.

As the years pass and I watch the Catholic Church descend ever further into doctrinal, moral, and liturgical chaos, I can no longer accept the opinion that Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre was guilty of “wrongful disobedience.”[9] He was caught in a terrible situation, with a hostile Vatican that seemed to care nothing for tradition (and my, how 2021 has brought us right back to that place), and a worldwide diaspora of traditional Catholics looking to him for a semi-stable solution. The imposition of the Novus Ordo and the aggiornamento theology launched by the Council was a kind of “Ostpolitik with Modernity” against which Lefebvre was rightly protesting, and against which he was willing to take a decisive step when the Faith appeared to be threatened like never before.

The actions of Wojtyła and Slipyj place Écône in a new light. That is not to say all difficulties evaporate, for on anyone’s accounting, friend or foe, it is not normal to have a society of priests operating in dioceses around the world without official jurisdiction, and one must pray for a happy resolution to an emergency situation precipitated by those who, derelict in duty, allowed the smoke of Satan—and now, rather obviously, heaps of burning faggots—to pervade the Church of God. When a building is burning down, one tries to put out the fire and rescue victims with any means to hand, rather than waiting until the fire brigade arrives—especially if one knows from bitter experience that the fire chief is absent from his post, or sleeping, or intoxicated, or convinced that fires are beneficial, and most of the firemen are bumbling idiots whose methods don’t work, or, worse, are paid by saboteurs to spray gasoline on the fire.

This much is clear: the crisis is not to be blamed on those who, conscious of an obligation in the sight of God, and a duty to suffering fellow believers, have responded to it as best they can, with the bright weapons of obedience to the ultimate law that governs all others: salus animarum suprema lex.

Lessons for Ourselves

If the Vatican, following on the heels of Traditionis Custodes, should dare to prohibit traditional priestly ordinations, it would be entirely justifiable for a bishop who understands what is at stake[10] to continue to ordain priests traditionally but clandestinely, without any permission requested or obtained. Even if the new rite of ordination is valid (as is the new rite of Mass), it is severely defective, unfitting and inauthentic in liturgical terms. The authoritative witness, priority, and superiority of the lex orandi of the traditional rite must be maintained in the life of the Church until such time as the Tridentine Pontificale Romanum can be universally restored.

At the same time, we see that Wojtyła and Slipyj acted clandestinely, which gives us a hint that actions like theirs do not need to be publicly announced and, as it were, made a spectacle of. They were responding to an immediate and desperate situation, as quietly and decisively as they knew how to do. In saying this, I am not implying the impossibility of a situation in which such actions could not rightly be done in broad daylight, but rather, pointing out that when material disobedience is required, normally the clandestine route is preferable to the public one.

This has obvious implications for our present situation. If a priest in good conscience chooses not to comply with unjust mandates or requirements emanating from ecclesiastical authority, he should not necessarily announce to the world that he will not be complying, but should simply not comply and carry on his pastoral and priestly work. If and when he is penalized, he should not make a big fuss about it, but ignore it and continue on. Again, the key word is normally: there may be times when open resistance is the best route, as in the possession of the Church of St. Nicolas du Chardonnet in Paris under the leadership of Msgr. Ducaud-Bourget and the repossession of the boarded-up church of Saint Louis du Port Marly.[11]

Unquestionably, the temptation to have instant recourse to social media, with the pros and cons of the popular support it generates, makes good discernment about the most prudential course of action (which might turn out to be “acting under the radar”) more difficult than ever.

Conclusion

One of the many ways in which Archbishop Lefebvre is being vindicated is this: he saw that he had to keep ordaining priests (and, for that matter, bishops) in the traditional rite. The usus antiquior is all of a piece—a unitary, coherent, inherited lex orandi embodying the lex credendi of the Catholic Faith. Yes, there are priests who were validly ordained in the new rite (as was archtraditionalist Fr. Gregory Hesse) and who later came to join the FSSP, SSPX, etc. But it is more important than most people realize to keep the old rites of ordination, at all levels, intact and alive.

If the Congregation for Divine Worship or the Congregation for Religious were to demand that the old rites of ordination be no longer used, that, too, will have to be for us a “non possumus” moment: this we simply cannot accept. But even more, it will be a time for the greatest challenge of all in the years ahead: will there be cardinals, archbishops, bishops, who, under such circumstances, are willing to confer Holy Orders clandestinely in the traditional rites? Our Lord who, in His Providence, bestowed upon us the glorious patrimony of the Church of Rome will surely arrange for its preservation in the hour of need.

[1] Weigel does not appear to have read Windswept House or he would be less naïve about Cardinal Agostino Casaroli (Cardinal Cosimo Mastroianni in Martin’s thinly-disguised fiction) or, for that matter, Paul VI.

[2] George Weigel, Witness to Hope: The Biography of John Paul II, rev. ed. (New York: Harper Perennial, 2020), 233.

[3] Some say that the prohibition against clandestine ordinations applied only to Czechoslovakia, so that Wojtyła, by having the seminarians come to him in Krakow, was cleverly sidestepping the issue, and not in fact acting in disobedience of any rule. This much is clear, however: the reason for the prohibition was to placate the Communist authorities, who would surely not have been pleased to learn that seminarians were just heading over the border to get ordained elsewhere (according to Jonathan Kwitny, Wojtyla was also ordaining secretly for the Church in the Ukraine, Lithuania, and Belarus). Hence the Vatican’s Ostpolitik would surely have stopped what Wojtyła was doing, had they found out about it. One could say, then, that what he did was contrary to the known or inferrable intention of the lawgiver, but not contrary to the purpose of any ecclesiastical law, namely, the salvation of souls. And that is my main point in all the examples discussed in this article. Just as man is not made for the sabbath, but the sabbath for man, so too the Church is not made for canon law, but canon law for the Church.

[4] The fact that Weigel learned of these ordinations only from a personal admission of John Paul II in 1996, as a footnote in his book at this place tells us, shows that Wojtyła’s conscience remained untroubled by what he had done: he had no intention of hiding it, at least after the dust had settled. It is also worth pointing out that if Wojtyła had received some kind of hint or indication from Rome that he should proceed (as Weigel gratuitously imagines), he would surely have mentioned this to Weigel when relating the story. But he did not, and it is in fact much more believable that there would be no discussion between Rome and Wojtyła on this point.

[5] Jonathan Kwitny, Man of the Century: The Life and Times of Pope John Paul II (New York: Henry Holt, 1997), 220.

[6] “Ukrainian Cardinals Husar and Slipyj are heroes to Church community,” The Catholic Register, June 22, 2017. According to another source, the year was 1977. At the time of writing, De Souza apparently recognized the beatification of Paul VI as legitimate; many traditional Catholics question both it and his “canonization.” For a full explanation, see Peter A. Kwasniewski, ed., Are Canonizations Infallible? Revisiting a Disputed Question (Waterloo, ON: Arouca Press, 2021), esp. 219–41.

[7] Jaroslav Pelikan, Confessor Between East and West: A Portrait of Ukrainian Cardinal Josyf Slipyj (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1990), 173. Interesting examples of Ostpolitik may be found throughout this book; see, e.g., pp. 182–86.

[8] The UGCC is a story of hope in its own right. Consider the following statistics and then apply them analogously to the state of the Latin-rite Church and liturgical “death and resurrection” from the 1960s to the present: “In 1939, the UGCC had some 3,000 priests in Ukraine. In 1989, after 50 years of war and persecution, the priesthood was reduced by 90 per cent, to just 300. At an average age of 70, the priesthood of the UGCC was just a generation away from extinction. Then came divine deliverance and the resurrection of a Church of martyrs. Nearly 30 years later, the UGCC has again 3,000 priests with an average age of 39. There are some 800 seminarians for five million Ukrainian Greek Catholics globally” (ibid.).

[9] I recommend the sympathetic but not uncritical treatment of Lefebvre found in H.J.A. Sire’s Phoenix from the Ashes: The Making, Unmaking, and Restoration of Catholic Tradition (Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2015), 410–30, et passim. I still believe, in line with this article I published here on April 3, 2019, that the SSPX chapels should be frequented in cases of emergency or moral impossibility, that is, if no other traditional parish or chapel in union with the local ordinary is available within a reasonable radius. I say that as someone who has absolutely no animus toward SSPX-goers, some of whom are personal friends, and certainly nothing less than the highest respect for the priests who continued to say Mass and administer the sacraments throughout the “pandemic” when the mainstream response was scandalously inadequate.

[10] Arguably no part of the liturgy suffered graver damage than the rites of ordination, which pertain most intimately to the existence and well-being of the Church on earth. A classic on this subject is Michael Davies’s The Order of Melchisedech, which, after a long time out of print, was recently republished by Roman Catholic Books (the link will take you to Sophia, which is distributing it). Davies shows the Protestantizing and modernizing distortion in the new rites of ordination and argues for the urgency of retaining and restoring the traditional ones. For a close comparison of the new and old rites with some striking conclusions, see Daniel Graham, Lex Orandi: Comparing the Traditional and Novus Ordo Rites of the Seven Sacraments (n.p.: Preview Press, 2015), 159–85. I hope to revisit these topics in a future article.

[11] To read more about the heroism of this postconciliar generation, see https://rorate-caeli.blogspot.com/2020/12/resistance-is-never-futile-interview.html.