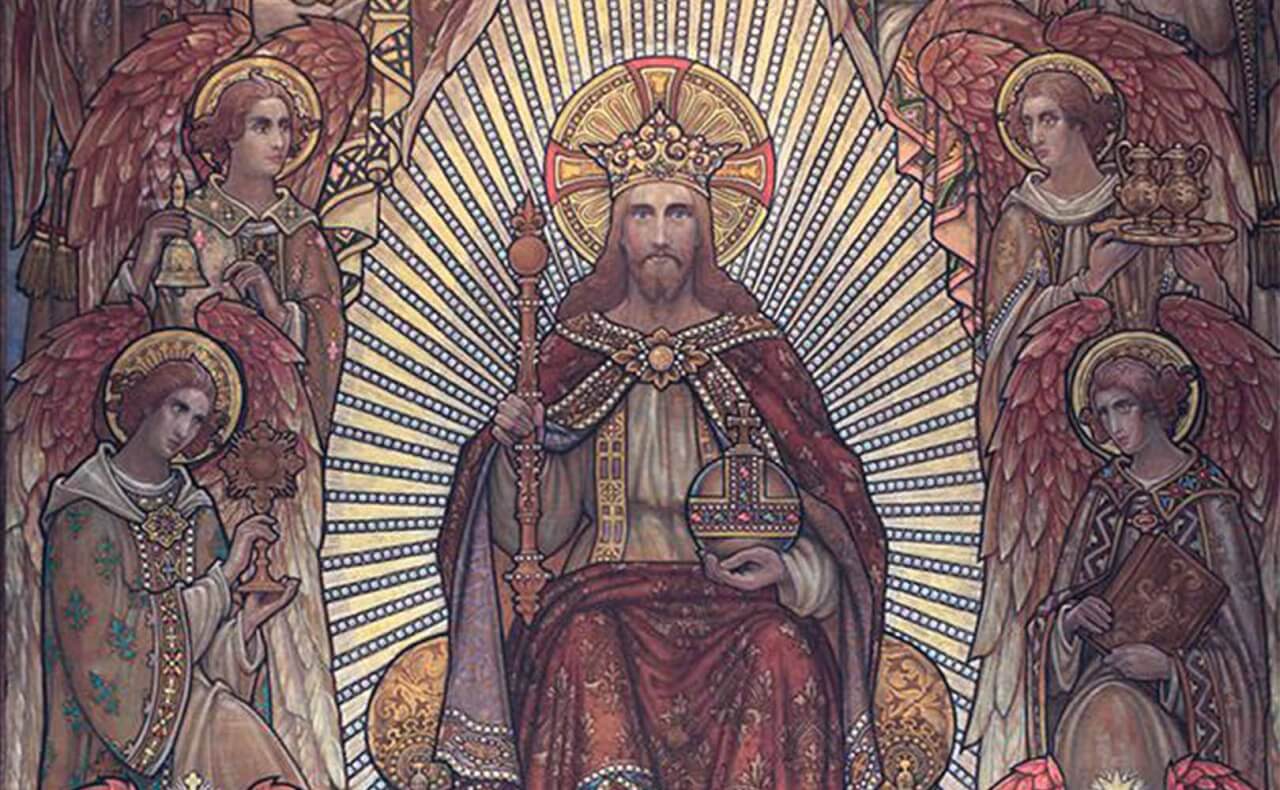

The month of November begins with the great Solemnity of All Saints. But in the traditional Roman calendar, All Saints is preceded shortly before by an even greater feast—that of Christ the King, the One who creates and sanctifies the citizens, ambassadors, and soldiers of His Kingdom.

When Pope Pius XI instituted the feast of Christ the King in 1925, he was, one might say, supplying in the Church’s calendar the missing invisible cause of All Saints, as well as making clear just what the mission of the saints in history is: to be the living members of the Mystical Body under Christ its Head, and to extend this body across the whole earth. Our Lord Jesus Christ is the King of all men, all peoples, all nations, and His saints are those who, taking up their cross and following Him, have conquered their own souls and won over the souls of many others for this Kingdom.

Pope Pius XI knew that in modern political circumstances, it was absolutely necessary to make this truth explicit, as he did in the great encyclical Quas Primas of December 11, 1925:

All men, whether collectively or individually, are under the dominion of Christ. In Him is the salvation of the individual; in Him is the salvation of society. … He is the author of happiness and true prosperity for every man and for every nation. If, therefore, the rulers of nations wish to preserve their authority, to promote and increase the prosperity of their countries, they will not neglect the public duty of reverence and obedience to the rule of Christ. … When once men recognize, both in private and in public life, that Christ is King, society will at last receive the great blessings of real liberty, well-ordered discipline, peace, and harmony. … That these blessings may be abundant and lasting in Christian society, it is necessary that the kingship of our Savior should be as widely as possible recognized and understood, and to the end nothing would serve better than the institution of a special feast in honor of the Kingship of Christ.

The right which the Church has from Christ Himself, to teach mankind, to make laws, to govern peoples in all that pertains to their eternal salvation—that right was denied [in the Enlightenment era]. Then gradually the religion of Christ came to be likened to false religions and to be placed ignominiously on the same level with them. It was then put under the power of the State and tolerated more or less at the whim of princes and rulers. … There were even some nations who thought they could dispense with God, and that their religion should consist in impiety and the neglect of God. The rebellion of individuals and States against the authority of Christ has produced deplorable consequences.

That was 1925. In Advent of 1969, a tidal wave of changes in Catholic worship came rolling through the Church. As we all know, among these changes was the moving of the feast of Christ the King from the last Sunday of October to the last Sunday of the liturgical year, at the end of November. Or at least that is what we think we know; it’s what I used to think, too. But that is not what actually happened.

As Michael Foley shows in a brilliant article in the latest issue of The Latin Mass magazine, the feast was not merely moved, but transmogrified. It was given a new name, a new date, and new propers, all of which deemphasized the social reign of Christ and put in its place a “cosmic and eschatological Christ.” That is not all:

According to no less an authority than Pope Paul VI, the Feast of Christ the King was not merely changed or moved; it was replaced. In Calendarium Romanum, the document announcing and explaining the new calendar, the Pope writes: “The Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ King of the Universe occurs on the last Sunday of the liturgical year in place of the feast instituted by Pope Pius XI in 1925 and assigned to the last Sunday of October….” The key word is loco, which means “in place of” or “instead of.” The Pope could have simply stated that the Feast occurs on a different date (as he did with the Feast of the Holy Family) or that it is being moved (transfertur) as he did with Corpus Christi, but he did not. The Novus Ordo’s Solemnity of Christ the King, he writes, is the replacement of Pius XI’s feast.[1]

Paul VI abolished Pius XI’s feast and replaced it with a new feast of the Consilium’s devising. There is common material, of course, but it is by no means intended to be the same feast on a different Sunday.[2]

Why did this happen? The simplest explanation, indeed the only one that fits the evidence, is that the apparent “integralism” of Pope Pius XI had become an embarrassment to such as Montini, Bugnini, and other progressives of the 1960s and 1970s. They had bought into the philosophy of secularism and wanted to make sure the liturgy did not celebrate the authority of Christ over the socio-political order or the regnant position of His Church within it. The modernized feast has to be about “spiritual” or “cosmic” or “eschatalogical” things, with a seasoning of “social justice.” As Foley writes: “The new feast guts the original of its intended meaning. … The liturgical innovators kicked the can of Christ’s reign down the road to the end of time so that it will no longer interfere with an easygoing accommodation to secularism.”[3] Not for them was the potent doctrine of St. Pius X:

That the State must be separated from the Church is a thesis absolutely false, a most pernicious error. Based, as it is, on the principle that the State must not recognize any religious cult, it is in the first place guilty of a great injustice to God; for the Creator of man is also the Founder of human societies, and preserves their existence as He preserves our own. We owe Him, therefore, not only a private cult, but a public and social worship to honor Him. Besides, this thesis is an obvious negation of the supernatural order. It limits the action of the State to the pursuit of public prosperity during this life only, which is but the proximate object of political societies; and it occupies itself in no fashion (on the plea that this is foreign to it) with their ultimate object which is man’s eternal happiness after this short life shall have run its course. But as the present order of things is temporary and subordinated to the conquest of man’s supreme and absolute welfare, it follows that the civil power must not only place no obstacle in the way of this conquest, but must aid us in effecting it. … Hence the Roman Pontiffs have never ceased, as circumstances required, to refute and condemn the doctrine of the separation of Church and State.[4]

What, then are we to make of the countless saints over the centuries who completely upheld this doctrine, lived for it and by it, defended and promoted it, advanced it to victory against every heathen and heretic? What of the saints who owed the birth and growth of their vocations—we could even say, in a way, the human conditions of their very sanctity—to the full-bodied, full-blooded Catholic society and culture in which they lived? And what, above all, do we make of that host of royal saints and blesseds whose holiness took the form of supporting the true Faith in their exercise of politics; people who saw the State as subordinate to the Church, this earthly life as subordinate to the life of the world to come, and believed that, in St. Pius X’s words, they “must not only place no obstacle in the way of this conquest [of heaven], but must aid us in effecting it”? Surely these saints have a special place in the Kingdom of God, where they rejoice in the just and pacific reign of Christ the King. They, above all, grasp the inner rationale of the close proximity of November 1st to the last Sunday of October.

When teaching Catholic social doctrine to college students, I never cease to be surprised at how many of them display the knee-jerk reaction of automatically assuming that monarchy is “mostly evil” and that democracy is “obviously good.” This seems to be a secular dogma imposed by our age and drilled in from tender years, especially in public schools. I like to shake people up by handing out the following list of royal saints and blesseds—the kings, queens, princes, princesses, dukes, duchesses, and other ruling aristocrats who are venerated, beatified, or canonized by Catholics, Orthodox, or Anglicans. Yes, this is a somewhat eclectic and ecumenical list, but surely it offers food for thought, since all of these individuals in obvious ways promoted and defended Christianity (and often Christendom, its full flowering) using their God-given political authority.[5]

First, a list of actual rulers:

Then a list of other royals and nobles:

Does modern democracy have a track record of sanctity like that? Where are the dozens of holy presidents, prime ministers, cabinet members, congressmen, mayors? You may object: Monarchy had many centuries of time during which saints could arise. Democracy as we know it is still relatively young. Give it a chance! To which I respond: modern democracy has been around now for over two centuries, and its track record is abysmal. One could count on both hands the men and women involved in democratic governments who have a reputation for heroic sanctity, let alone an acknowledged cultus.[7] Besides, look around you: do you think the prospects for great holiness emerging within democratic regimes is increasing as time goes on? In this case, it is no exaggeration to say that the myth of Progress looks more mythical than ever.

In a fallen world where all of our efforts are dogged by evil and doomed (eventually) to failure, Christian monarchy is, nevertheless, the best political system that has ever been devised or could ever be devised. As we can infer from its much greater antiquity and universality, it is the system most natural to human beings as political animals; it is the system most akin to the supernatural government of the Church; it is the system that lends itself most readily to collaboration and cooperation with the Church in the salvation of men’s souls. Yes, it goes without saying that there have been plenty of tensions all along between Church and State—but will those ever be absent, in any political arrangement whatsoever? Are they absent in democracy—or have we obtained what seems like peace at the cost of any real influence in society? Has not the Church simply been demoted to the status of a private bowling league that can be permitted or suppressed at whim? The usual defense of religious liberty today is only as strong as the Enlightenment concepts it depends upon, and these concepts were already branded as falsehoods by a string of popes from the time of the French Revolution down to Pius XI.

The two wisest men of pagan antiquity, Plato and Aristotle, maintained that democracy, far from being a stable form of government, is always teetering on the edge of anarachy or tyranny. In spite of his predilection for democracy, Pope John Paul II could not fail to acknowledge the same danger in three separate encyclicals:

Nowadays there is a tendency to claim that agnosticism and skeptical relativism are the philosophy and the basic attitude which correspond to democratic forms of political life. Those who are convinced that they know the truth and firmly adhere to it are considered unreliable from a democratic point of view, since they do not accept that truth is determined by the majority, or that it is subject to variation according to different political trends. It must be observed in this regard that if there is no ultimate truth to guide and direct political activity, then ideas and convictions can easily be manipulated for reasons of power. As history demonstrates, a democracy without values easily turns into open or thinly disguised totalitarianism.[8]

Today, when many countries have seen the fall of ideologies which bound politics to a totalitarian conception of the world—Marxism being the foremost of these—there is no less grave a danger that the fundamental rights of the human person will be denied and that the religious yearnings which arise in the heart of every human being will be absorbed once again into politics. This is the risk of an alliance between democracy and ethical relativism, which would remove any sure moral reference point from political and social life, and on a deeper level make the acknowledgement of truth impossible.[9]

If the promotion of the self is understood in terms of absolute autonomy, people inevitably reach the point of rejecting one another. Everyone else is considered an enemy from whom one has to defend oneself. Thus society becomes a mass of individuals placed side by side, but without any mutual bonds. Each one wishes to assert himself independently of the other and in fact intends to make his own interests prevail. … This is the sinister result of relativism which reigns unopposed: the “right” ceases to be such, because it is no longer firmly founded on the inviolable dignity of the person, but is made subject to the will of the stronger part. In this way democracy, contradicting its own principles, effectively moves towards a form of totalitarianism. … Even in participatory systems of government, the regulation of interests often occurs to the advantage of the most powerful, since they are the ones most capable of maneuvering not only the levers of power but also of shaping the formation of consensus. In such a situation, democracy easily becomes an empty word.[10]

We may have deluded ourselves into thinking that we have stability, peace, and justice—“Where’s the anarchy? Where’s the tyranny?”—but, as Hans Urs von Balthasar once wrote, the entire contemporary Western social order is founded on the blood of millions of butchered unborn children, whose murder is permitted and protected by the State. And this is only one of the many pervasive sins of our democratic era that cry out to God for vengeance. This hardly sounds like a system of which Catholics ought to be proud. Rather, they should rue it, repent of it, and beg the Lord for deliverance.

Right now, the prospects for Catholic monarchy seem dim, to say the least. But we ought to have the courage to admit that what we are doing is not working, that we are digging ourselves collectively into the deepest and darkest pit human history has ever seen. Compared to this, I would prefer to take my chances on monarchy and aristocracy. In all of its checkered episodes, it still has a proven track record of sanctity and defense of the Faith. Nothing else does.

This leads me back to Pope Paul VI’s suppression of one feast of Christ the King and his creation of another. What is really going on here? It seems to me that the original feast of Christ the King represents the Catholic vision of society as a hierarchy in which lower is subordinated to higher, with the private sphere and the public sphere united in their acknowledgment of the rights of God and of His Church. This vision was put aside in 1969 to make way for a vision in which Christ is a king of my heart and a king of the cosmos—of the most micro level and the most macro level—but not king of anything in between: not king of culture, of society, of industry and trade, of education, of civil government.

In other words, for such middling spheres, “we have no king but Caesar.” The impious cry of the ancient Jews has become our foundational creed. We have bought into the Enlightenment myth of the separation of Church and State, which, as Leo XIII says, “is equivalent to the separation of human legislation from Christian and divine legislation.”[11] The result cannot but be catastrophic, as we unmoor ourselves from the very aids God has provided to our human weakness. If we see a world crashing around us into unimaginable deviancy and we seek the cause, let us not be afraid to pursue it back to the rebellion of the modern revolutions—from the Protestant Revolt down to the French Revolution and the Bolshevik Revolution—against the social order of Christendom, which blossomed in the sacral kingship of Christian monarchs.

I am certainly not saying that we can snap our fingers and find ourselves in a renewed Christendom. The original version took centuries to build up. It would take several centuries to build up a new version of Christendom. But the only way we are going to get there is by seeing the ideal for what it is, yearning for it, and praying for the reign of Christ the King to descend into our midst with all the realism of the Incarnation, that He may sanctify anew the world He came to save. In this time before the end of time, when all politics and all visible rites give way to the blazing glory of His advent, we are not to throw up our hands, yielding everything to the juggernaut of “Progress,” which is another word for decadence and depravity. It belongs to soldiers of Christ to acknowledge their King and to fight for His acknowledgment. Come what may, this is how each one of us shall win through to an imperishable crown in the eternal kingdom of heaven.

NOTES

[1] Michael P. Foley, “Reflecting on the Fate of the Feast of Christ the King,” The Latin Mass, vol. 26, no. 3 (Fall 2017): 38–42; here, 41, emphasis added.

[2] For various examples of the kinds of changes made—some glaring and others subtle—see Foley’s article mentioned in note 1; Dylan Schrader, “The Revision of the Feast of Christ the King,” Antiphon 18 (2014): 227–53; Peter Kwasniewski, “Should the Feast of Christ the King Be Celebrated in October or November?”.

[3] Foley, “Reflecting on the Fate,” 41–42.

[4] Pius X, Encyclical Vehementer Nos to the French Bishops, Clergy, and People (February 11, 1906), n. 3.

[5] These lists are taken from Wikipedia’s entry Royal Saints and Martyrs, which suffices for our purpose here. Incidentally, it is obvious from the Magisterium of the Church that even non-Catholic rulers have their authority from God and received it precisely to promote natural law morality and the Christian religion: see, inter alia, Leo XIII’s Encyclical Diuturnum Illud.

[6] The cultus of Charlemagne was permitted at Aachen.

[7] An example would be Robert Schuman, one of the founding fathers of the European Union—the contemporary debased form of which he would scorn. Other examples might be António de Oliveira Salazar in Portugal; Engelbert Dollfuss in Austria; Gabriel García Moreno of Ecuador; Éamon de Valera in Ireland.

[8] John Paul II, Encyclical Centesimus Annus (May 1, 1991), n. 46.

[9] John Paul II, Encyclical Veritatis Splendor (August 6, 1993), n. 101.

[10] John Paul II, Encyclical Evangelium Vitae (March 25, 1995), n. 20; n. 70.

[11] Leo XIII, Encyclical Au Milieu des Sollicitudes to the Church in France (February 16, 1892), n. 28.

Originally published on November 8, 2017.