I will never forget what it was like to watch the Lord of the Rings films for the first time, when I was eleven or so. I had always devoured books, but the story of Frodo and the ring was in another class than anything I had yet experienced in my young life. I remember the wonder of following those characters across Middle Earth, forgetting for minutes at a time that what I was watching was not history, but the imaginings of one British gentleman. Soon after, my mother, sisters, and I borrowed all of the extended edition DVDs and spent eleven hours watching them one after the other. As the characters struggled on for years, through distant lands, through deadly battles, we struggled on with the weariness of staying put for several hours, paying attention to something, making some small sacrifice of our own in order to more fully experience the weight of the epic tale.

The end came, the black screen, the credits, the sudden return to mundane life, the popcorn dishes waiting to be washed, and I understood some shadow of how Frodo must have felt: “How do you pick up the threads of an old life? How do you go on, when in your heart, you begin to understand…there is no going back? There are some things that time cannot mend. Some hurts that go too deep, that have taken hold.” And, I would add, there are some stories that cling so deeply to us that we are never quite the same as before we heard them.

Tolkien’s world was formative for me. I read The Lord of the Rings trilogy as a preteen, making my way through the slower chapters (filled with seemingly endless details, many of which I was too young to understand) as an act of the will, not concerned with the cost of time and energy. In a very real way, long before my conversion, these books helped me to look beyond the smallness of my life and to see the bigger things that constitute the human condition: good and evil, love and hate, loyalty and betrayal, bravery and cowardice.

After my conversion, I realized just how much I had to learn about our faith, and consequently, I spent virtually all of my reading time on Catholic non-fiction books. This was well and good, but I realized that when it came to reading for pleasure, I usually found myself choosing things I could skim the surface of, things I could rush, things that checked the boxes for being the “best” use of my time. This is actually insidious — Satan knows that it is impossible for us to give up all leisure, so instead, he tricks us into believing that innocent-but-instant-dopamine-hit entertainment is always preferable to the more time-consuming enjoyment of true culture!

A month or so ago, I found a 700-page fantasy novel called The Name of the Wind, a paperback in perfect condition, nestled onto a cluttered rack in the back room of the thrift shop. I’d heard about it for months. It was fifty cents. Buying this book took courage. It’s so long, so bricklike, with such tiny writing… It’s the sort of book that was making a demand of me, a challenge that I wasn’t sure I had the energy for. And yet, I remembered stories like The Lord of the Rings, and I knew that the demands of good books are worth it in the end.

Despite its (quite minor, in my view) flaws in terms of moral content and one very feminist character I strongly dislike, I am so happy that I read that story, and so far, I am enjoying book two just as much. As it happens, I tore through it in week. I do not for a moment believe that God is upset with me that I slowed my pace reading my latest Catholic apologetics tome for a few days in order to manage it.

Laramie Hirsch wrote a fantastic article in defense of Catholics reading fantasy back in 2018, and this passage especially struck me:

The mind can tolerate a wasteland for only so long. Men require a pilgrimage and retreat. Otherwise, one settles for vice and debasement. Experiencing wonder is necessary for a mature mind. It is not enough to be raised in a plain fashion, learning good moral habits to live by as if it’s all a simple matter of hygiene. Becoming a lawyer for “what’s good and what’s bad” does not securely instill the Faith in children, who, above all, are in the business of make-believe. No, we must leave the districts and subdivisions gerrymandered in our brains. We must fly above the rooftops from our suburban bobo communities. We’ve got to run for our lives into something fresh, new, and perhaps even dangerous.

I have grappled with these dichotomies for most of my time as a Catholic. How do I hold fast to the rules with unfailing loyalty, while also allowing for the beauty of our faith to shape the beauty of our cultural pursuits? Where is the moral line as to what we will look at, listen to, or read? How do I teach the faith to my son and future children, while hopefully teaching them to love getting lost in their imaginations as much as I do? While I don’t have all of the answers to these questions, I do know the path that I will follow in order to figure it out — as in all things, we find sure footing if we are near to Our Lady.

For a very long time now, my favorite mystery of the rosary has been the Coronation of Mary as Queen of Heaven and Earth. I struggle with visual meditation, but I find this mystery to be one of the easiest. I see myself kneeling before Our Lady, as she lays a beautiful sword across each of my shoulders in turn. I renew my consecration, I give myself to her entirely, I see myself as a knight in her service, prepared to die for her if need be. Then she turns, facing away from me, as Our King and Lord Jesus Christ enters the hall. She kneels before him, and we do the same, her majesty as Queen paired with her perfect humility in service of Him who is infinitely above her.

Recently, I discovered a prayer in my Father Lasance Missal that I say almost daily now, so perfectly does it encapsulate how I feel when I reflect on my Marian consecration, pray the Three Hail Marys, or say my rosary:

O Sovereign and true leader, O Christ, my King, I kneel before Thee here like a vassal in the old feudal times to take my oath of fealty. I place my joined hands within Thy wounded hands and promise Thee inviolable loyalty. I dedicate to Thee all the powers of my soul, all the senses of my body, and all the affections of my heart. Take, O Lord, all my liberty. Receive my memory, my understanding, and my whole will. All that I am, all that I have, Thou hast given me, and I restore it all to Thee, to be disposed of according to Thy good pleasure. Give me only Thy love and Thy grace; with these I am rich enough, and I desire nothing more.

Where is the sterility in this prayer? Where is the “just do what you’re supposed to do, feelings don’t matter” attitude that is far too often inserted into discourses where it does not belong? Sentimentality can be dangerous. Emotionalism can be dangerous. But so too can be a faith without beauty, a faith without wonder, a faith that does not allow for silly songs to be sung or epic tales to be told. A faith like this will never produce another Adoro Te Devote or Sistine Chapel.

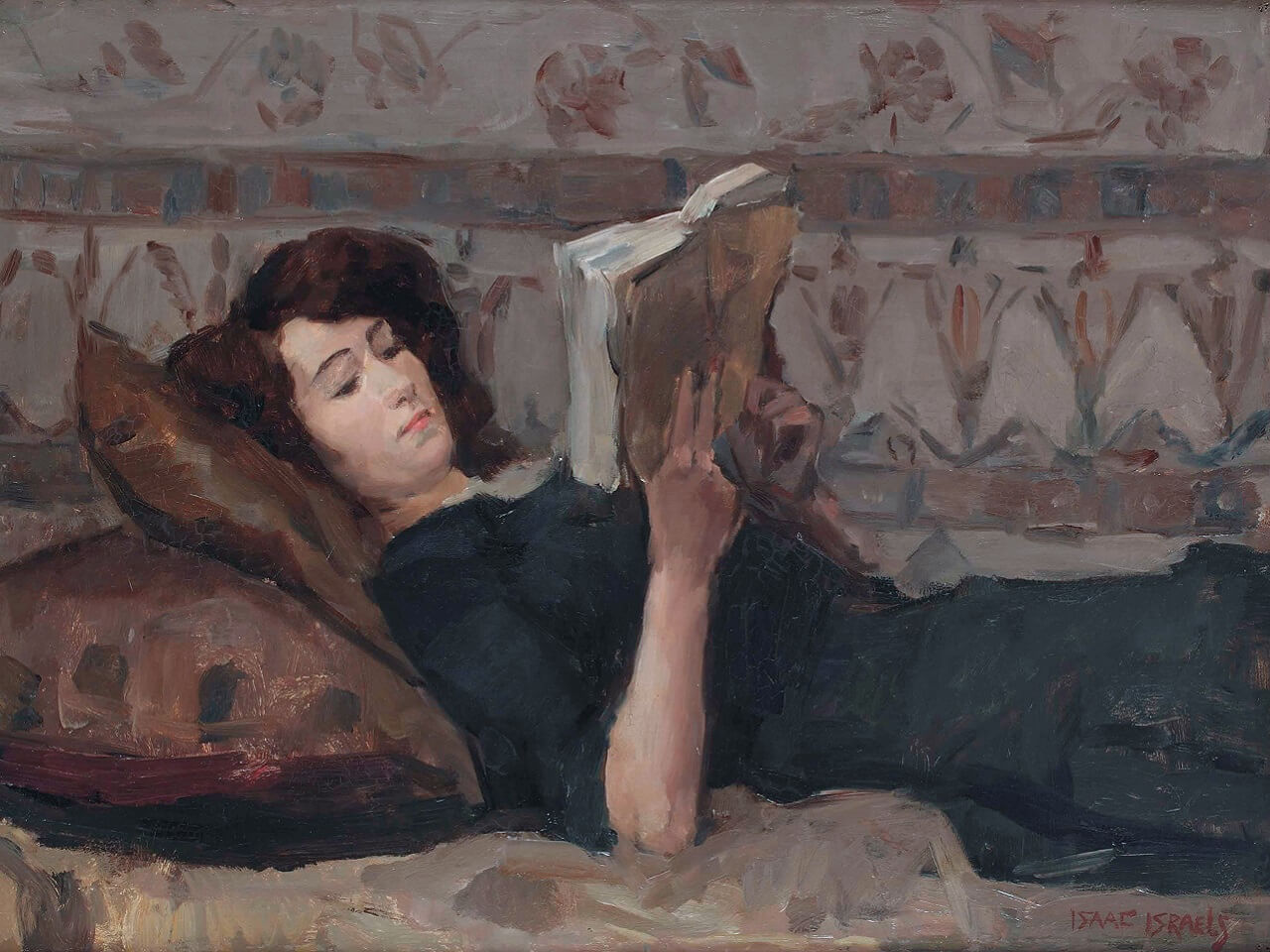

There is nothing more awe-inspiring than the story of salvation, it’s true, but it does not follow that we must cast aside those stories that lead us to live our parts in it with a deeper devotion and love — be they found in books, art, film, or song. If we wish to restore Catholic culture, if we wish to change the world, we need to fill ourselves with wonder and allow our children to see it, too. They will — if we don’t get in the way with our utilitarianism and coldness. We need to take the time for thick blankets and hot mugs of tea, lazy Saturday afternoons spent poring over pages, wasting away hours on joys so many of us have forgotten.

I will kneel before the altar of God, I will receive my King upon my tongue, I will offer my oath of fealty in coins and candleflame, and I will read a good book on the car ride home.