The Church’s most urgent need… How would you define it? Here is how Bishop Athanasius Schneider once answered the question:

Before we can expect efficacious and lasting fruits from the new evangelization, a process of conversion must get under way within the Church. How can we call others to convert while, among those doing the calling, no convincing conversion towards God has yet occurred, internally or externally? … No one can evangelize unless he has first adored, or better yet unless he adores constantly and gives God, Christ the Eucharist, true priority in his way of celebrating and in all of his life.

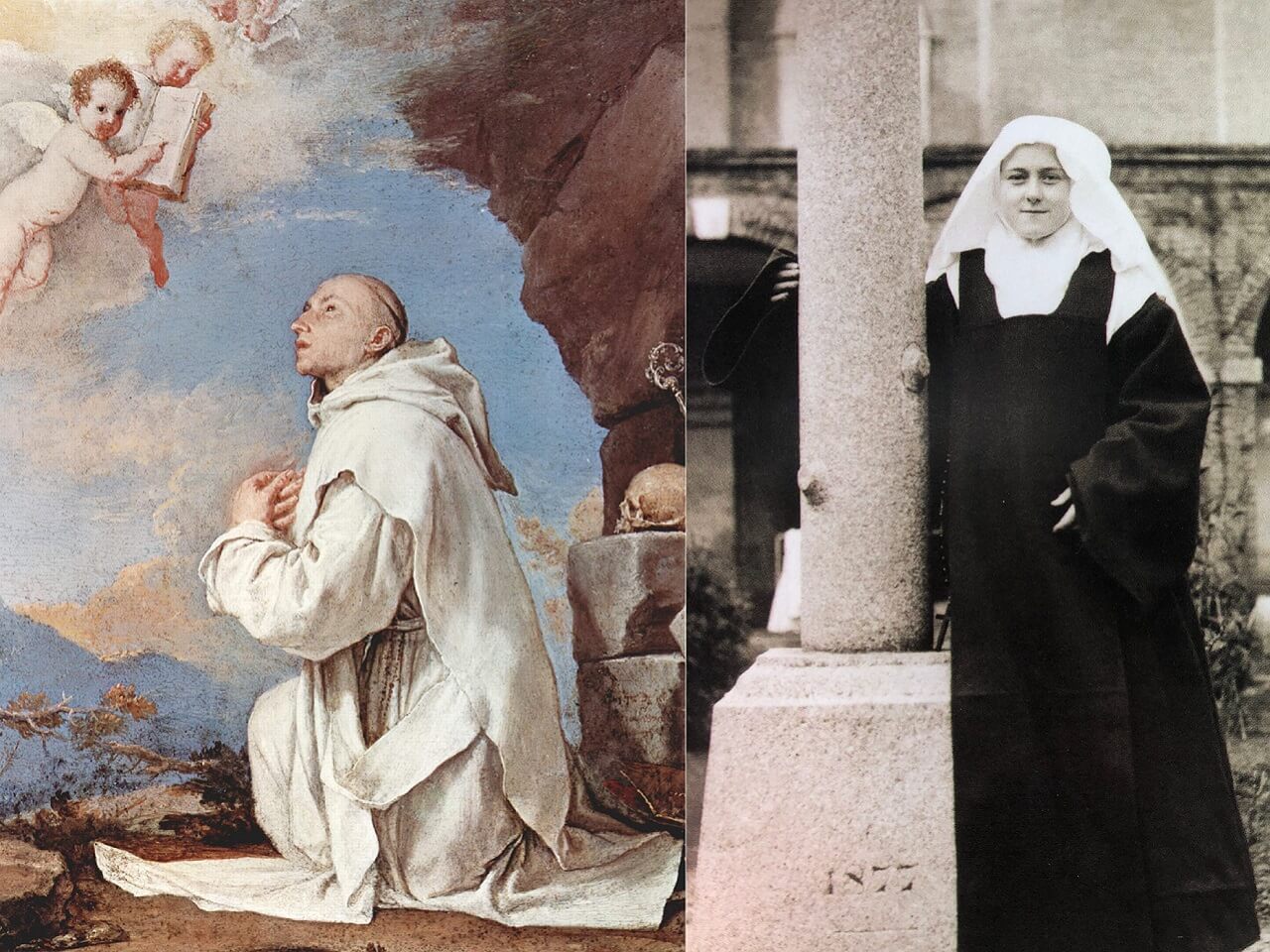

The first week of October brings with it the feasts of two great contemplative religious: St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus and of the Holy Face (1873–1897; it’s always good to remind ourselves of her full name in religion), one of the most famous Carmelites of all time, whose feast is October 3 on the old Roman calendar, October 1 on the new; and then, on October 6, St. Bruno of Cologne (ca. 1030–1101), founder of the most inaccessible and austere community of religious in the world, the Carthusians, memorably documented in the award-winning film Into Great Silence.

Both Thérèse and Bruno lived much of their adult lives in seclusion, silence, prayer, and penance, far removed from the hustle and bustle of civil society. They did not engage the battles of the world with the weapons of flesh and blood, campaigning for this or that party or platform, signing petitions, doing interviews, or the like. They did not pound the pavement for the New Evangelization. They did not wait expectantly for the latest pastoral program from the regional bishops’ conference. Their fight was quieter and more extreme: the internal struggle for heroic sanctity and perfection in charity, doing their Purgatory on Earth, and already living the life of the world to come. They knew the central secret: God is worthy of all our love, of receiving everything we can give Him. This radical gift of self is what made them and their work supernaturally and superabundantly fruitful. St. Bruno founded an order that has endured for almost a thousand years. St. Thérèse has touched more lives than any other saint of modern times.

What is the perspective of the secular world on the contemplative religious life? It is expressed well by the agnostic Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume:

Celibacy, fasting, penance, mortification, self-denial, humility, silence, solitude, and the whole train of monkish virtues; for what reason are they every where rejected by men of sense, but because they serve to no manner of purpose; neither advance a man’s fortune in the world, nor render him a more valuable member of society; neither qualify him for the entertainment of company, nor increase his power of self-enjoyment?

Regrettably, this view — so entirely opposed to that of the Catholic Faith, which has always accepted with childlike trust the Lord’s judgment: “Mary has chosen the better part” (Lk. 10:42) and “Seek first the Kingdom of God” (Mt 6:33) — has also penetrated into the ranks of Catholics, to such an extent that it is rather likely to be the response of parents, siblings, and friends to any young man or woman who declares that he or she is going to enter a cloistered community like the Carthusians or the Carmelites.

We can see a particularly clear example of how the tendency of activism has entered into the modern Church by looking at Archbishop John Ireland (1838–1918), who, in his introduction to The Life of Father Hecker by Fr. Walter Elliott (1891), wrote:

The Church is nowadays called upon to emphasize her power in the natural order. God forbid that I entertain, as some may be tempted to suspect me of doing, the slightest notion that vigilance may be turned off one single moment from the guard of the supernatural. For the sake of the supernatural I speak. And natural virtues, practised in the proper frame of mind and heart, become supernatural. Each century calls for its type of Christian perfection. At one time it was martyrdom; at another it was the humility of the cloister. To-day we need the Christian gentleman and the Christian citizen. An honest ballot and social decorum among Catholics will do more for God’s glory and the salvation of souls than midnight flagellations or Compostellan pilgrimages.

“Natural virtues, practised in the proper frame of mind and heart, become supernatural.” Unfortunately, Your Excellency, this is not how it works. While it is true, as St. Thomas Aquinas teaches, that grace builds on nature — the normal way to prepare for supernatural grace and contemplative union is to acquire and live the natural virtues such as prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance[1] — there is a basic incommensurability between the natural order and the supernatural order. They are different not just in degree, but in kind. This is why you can find pagan Romans of superb courage and other lofty virtues who nevertheless despised the teaching of Christ and who persecuted Christians; and you can find notorious sinners like Saul who, by God’s inscrutable purpose and omnipotent command, were transformed in a moment from hating the Name of Jesus to zealously loving it. The natural virtues at their best prepare us to receive God’s gift of sanctifying grace, but they do not establish a right to it, nor is God bound to operate by their limitations.

Put simply: You cannot get to supernatural Union Station from the natural country junction; they do not share a common set of railroad tracks. You cannot go to Heaven from Earth, no matter how well you tread the paths of this world; you cannot lift yourself up to theological virtues by acquiring lots of moral and intellectual virtues. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, as true and admirable a treatise as it is, does not culminate in a baptism of desire, water, or blood. Between a fine university education and divinization in Christ groans an abyss that cannot be crossed by man’s engineering. God must come down to Earth from Heaven and lift us up to Himself by the infused gifts of faith, hope, and charity; the infused moral virtues; and the gifts and fruits of the Holy Ghost. The supernatural presupposes, heals, and elevates the natural, but the natural, all by itself, will remain forever natural.

To put it in terms familiar from another Enlightenment thinker, Sir Isaac Newton: “Every body persists in its state of being at rest or of moving uniformly straight forward, except insofar as it is compelled to change its state by force impressed.” In a similar way, human activity remains merely human and does not become adoration, charity, service of God until it is permeated with divine grace. Prayer and the sacramental life are what give glory to God and save souls — and it is these activities to which the Church’s mission is in fact ordered.

A contemporary of Ireland’s, Dom Prosper Guéranger (1805–1875) understood this perhaps better than anyone else in his century. In his classic fifteen-volume work The Liturgical Year, which has introduced countless Catholics to the riches of the traditional Roman liturgy, he takes the feast of St. Bruno as his opportunity for an extended paean to the contemplative life:

Among the diverse religious families, none is held in higher esteem by the Church than the Carthusian; the prescriptions of the corpus juris [canon law] determine that a person may pass from any other Order into this, without deterioration. And yet it is of all the least given to active works. Is not this a new, and not the least convincing, proof that outward zeal, how praiseworthy soever, is not the only, or the principal thing in God’s sight?

The Church, in her fidelity, values all things according to the preferences of her divine Spouse. Now, our Lord esteems His elect not so much by the activity of their works, as by the hidden perfection of their lives; that perfection which is measured by the intensity of the divine life, and of which it is said: “Be you therefore perfect, as also your heavenly Father is perfect.” Again it is said of this divine life: “You are dead and your life is hid with Christ in God.” The Church, then, considering the solitude and silence of the Carthusian, his abstinence even unto death, his freedom to attend to God through complete disengagement from the senses and from the world — sees therein the guarantee of a perfection which may indeed be met with elsewhere, but here appears to be far more secure. Hence, though the field of labour is ever widening, though the necessity of warfare and struggle grows ever more urgent, she does not hesitate to shield with the protection of her laws, and to encourage with the greatest favours, all who are called by grace to the life of the desert.

The reason is not far to seek. In an age when every effort to arrest the world in its headlong downward career seems vain, has not man greater need than ever to fall back upon God? The enemy is aware of it; and therefore the first law he imposes upon his votaries is, to forbid all access to the way of the [evangelical] counsels, and to stifle all life of adoration, expiation, and prayer. For he well knows that, though a nation may appear to be on the verge of its doom, there is yet hope for it as long as the best of its sons are prostrate before the Majesty of God.

Curious, isn’t it, how Archbishop Ireland sounds a lot more like Hume than he does like Guéranger? And dare one ask: Which of them sounds more like Our Lord Jesus Christ? It is a question that could be posed of many another high-ranking cleric today.

The Church thinks as Guéranger, or rather, he faithfully transmits her mind. Instead of making St. Francis Xavier, who baptized 300,000 pagans, the sole patron of the missions, the Church declared St. Thérèse of Lisieux, who never left the four walls of her convent, co-patroness of the missions. It is worth noting that all five daughters in Louis and Zélie Martin’s family became religious: four of them Carmelite nuns, and the fifth a Visitation sister. This, evidently, was not a family in which “evangelizing out in the streets” was the primary ideal. Rather, they cherished a great love for personal and liturgical prayer and for the contemplative life, which are not only not in tension with charity for the poor and evangelizing, but are its fundamental preconditions and safeguards. Without prayer, without a vivid awareness of the existence, goodness, and authority of God, human beings will not be able to retain even a belief in human dignity, as the coldhearted spread of abortion and euthanasia demonstrates.

According to St. Thomas Aquinas, it is not necessary that everyone follow the contemplative life in order for society to be healthy, yet it is necessary that some men and women do this, for several reasons. First, in living a life dedicated wholly to God, they are choosing the greatest good in itself and for themselves, and without some doing this, the Church as a whole would be disordered and unfaithful. Second, in so cleaving to God, these religious are more pleasing to Him and thereby will His blessings on the rest of us; they act as Moses on the mountainside, obtaining pardon for the people. Third, they serve as a perpetual reminder to the rest of us of “the life of the world to come,” for which we must prepare ourselves during this life, whatever path in life we tread. These are the last words of the Creed: et vitam venturi saeculi, amen. At the Latin Mass, we make the sign of the cross when these words are spoken or sung. It is by the power of the cross, by self-denial, by entering the humility of Christ, that we will achieve eternal life: so be it. Some men and women must make their entire lives into this amen.

For Archbishop Ireland, as for today’s progressives and neoconservatives in the Church, we don’t need contemplatives anymore, in our advanced stage of maturity; we need active people. How prescient Pope Leo XIII was to condemn Ireland’s “Americanism,” with its characteristic exaltation of the “active” over the “contemplative”!

In his Apostolic Constitution Umbratilem of July 8, 1924, approving the Statutes of the Carthusian Order, Pope Pius XI repeated and confirmed his predecessor’s judgment:

There are perhaps some who still deem that the virtues which are misnamed passive have long grown obsolete and that the broader and more liberal exercise of active virtues should be substituted for the ancient discipline of the cloister. This opinion our predecessor of immortal memory, Leo XIII, refuted and condemned in his Letter Testem Benevolentiae given on January 22 in the year 1899. No one can fail to see how harmful and pernicious that opinion is to Christian perfection as it is taught and practiced in the Church.

As if it had been stuffed down into a canister and not eradicated, this Americanism, like its cousin Modernism, burst forth again with a vengeance after the Second Vatican Council, which many observers described as a triumph of combined American pragmatism and French nouvelle théologie. Without a doubt, St. Bruno and St. Thérèse would counsel us — with Pope Leo, Pops Pius XI, and Dom Guéranger — to repent and believe in the Gospel once again.

Love for God above all, expressed in a life of conversion and adoration, is the precious and timely lesson taught to us, demonstrated for us, by St. Bruno and St. Thérèse. In one of his rare canonization decrees, Pius XI wrote the following (it was about a different Carmelite, Therèse-Marguerite Redi, but the description is meant to apply to all consecrated contemplatives):

By the supreme martyrdom of heart, the loving soul attached to the cross with Christ acquires for itself, and for others, more abundant fruits of redemption. In fact, it is such very pure and very lofty souls that, by their sufferings, their love and their prayer, silently fulfill that apostolate which is the most universal and the most fruitful of all in the Church.

May the Lord raise up once again, in our times, such very pure and very lofty souls. Indeed, may He raise up more and more of them. The health of the Church radically depends upon their sufferings, their love, and their prayer.

[1] So much is this true that, normally speaking, no one would be deemed suitable for entering religious life or contemplative life who did not display at least a balanced psyche (e.g., free from such things as homosexual inclinations, paranoia, abnormal scrupulosity, or uncontrolled temper), the rudiments of acquired natural virtues, and a commitment to asceticism. Such conditions may be compared to the healthy soil in which the vine of grace will flourish and bear abundant fruit. It is true that God, operating independently of the natural order, can choose to make bad soil into good soil, but His human representatives are not entitled to assume that He will perform such a miracle; they must proceed on the basis of discernible human capacities for success in a difficult undertaking.