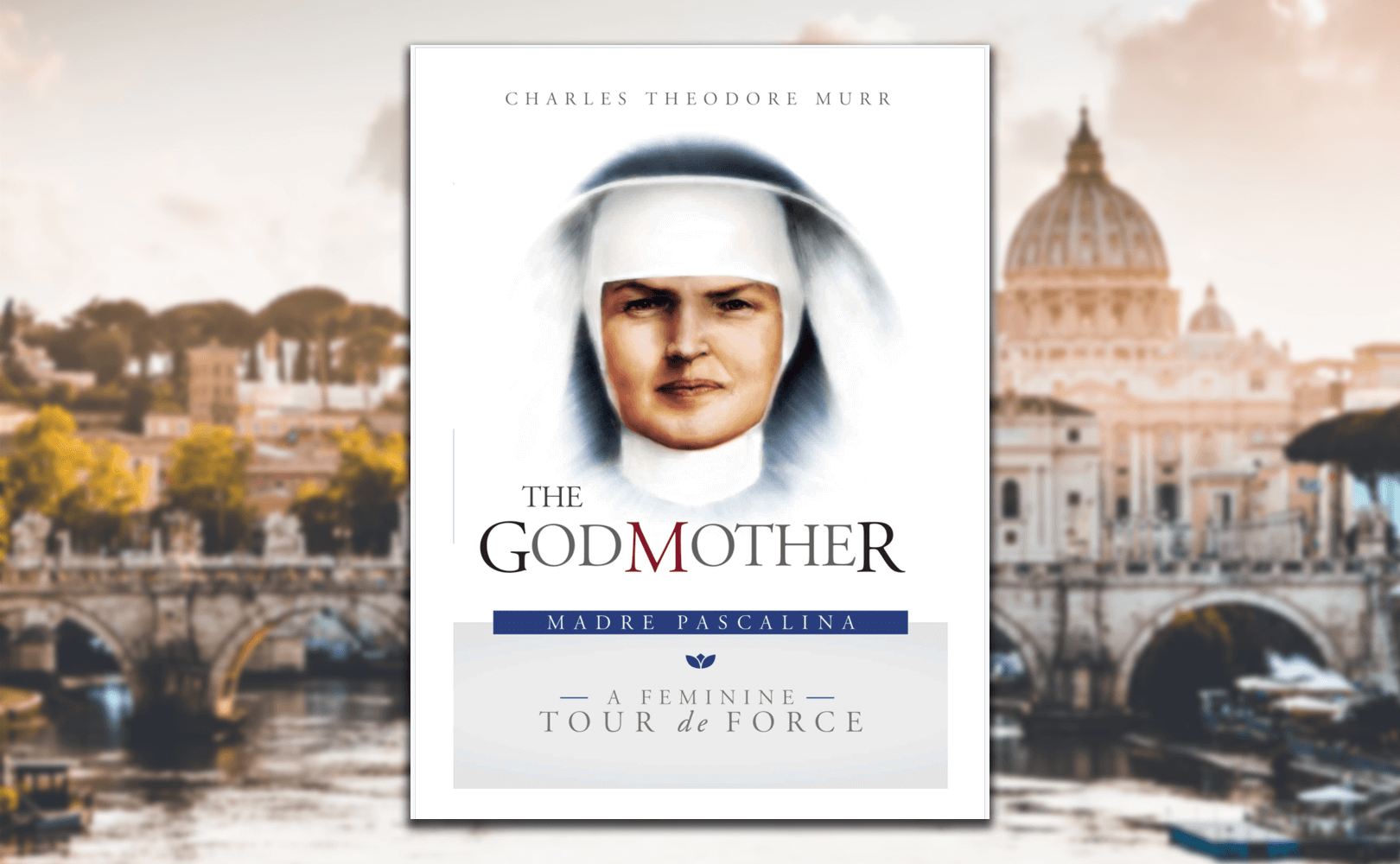

The Godmother: Madre Pascalina, a Feminine Tour de Force

Author: Charles T. Murr

Publisher: Enrique J. Aguilar

304 Pages

$9.95 Kindle; $24.95 Paperback

Charles Theodore Murr is a Catholic Priest from the archdiocese of New York now retired. During his time as a Seminarian in Rome in the 1970s, he had the blessing of befriending the great Madre Pascalina (1894-1983), the secretary to Ven. Pius XII, and claiming her as his godmother. The two enjoyed a close spiritual friendship and spent countless Roman afternoons discussing the state of the Church during the twilight of Papa Montini’s pontificate. Murr’s book The Godmother recounts these conversations and offers a view at the Church crisis from the closest confidant of Pius XII, providing a unique perspective from her who had been the most powerful woman in the Vatican. The book was published in 2017 before the “summer of shame” and very few took notice. But now as we have endured these few years of scandal and the debate about Vatican II has once again been opened by Archbishop Viganò, Murr’s book deserves another look by faithful Catholics.

Most books which discuss the subject of controversy in the Vatican are sensationalist, pessimistic, or else wildly speculative. Murr’s book manages to avoid these pitfalls and makes for great reading. The conversations as recorded by Murr create a friendly and cordial look at a dire situation in the 1970s. Madre Pascalina may indeed be a saint, because there is a saintly charm that runs through this book, even as numerous dark stories are told. Pascalina speaks with the confidence of a friend of God, the humor of the great saints and the straight talk of a pious nun. Murr writes of his conversations in the third person and tells the story of friendship through the hardship of crisis. This is truly a great lesson for faithful Catholics, as so many spend hours on the internet in dour melancholy or bitter complaining. What Murr shows is the power of true friendship in Christ, which is truly an extraordinary blessing in hard times. It also shows the great need for the faithful to support our priests in our day.

During the course of the book Pascalina offers many amusing anecdotes of Vatican politics. In our age of rapid canonizations, she shares about the canonization process of Pius IX and Pius X. According to Pascalina, Pius XII wanted Pius X canonized after his fourth miracle and he was eager to have the world contemplate his holiness, whom Papa Pacelli believed to be the model pastor for our times. But when Pius XII consulted with Padre Antonelli, charged with Pius X’s cause, he learned that it would be another fifty years before Pius X was canonized. Wanting the process wrapped up as soon as possible, Pius XII came to his trusted secretary, Madre Pascalina:

“He asked ‘Of all the convents in the Holy Cross Order of Menzingen [the religious order to which Mother Pascalina herself belonged] which is the most remote—the furthest from a town; with the most inclement weather; the worst cook and cuisine; and the most uncomfortable beds?’

“Immediately, the little retreat house our order had in the Swiss Alps, far beyond Lausanne, came to mind,” [Pascalina] said with a chuckle, “I knew the cook there, quite well. She did her best but…” (66)

At this Pius XII instructed Pascalina to give Antonelli the “good news” of his winter retreat in the alps. Antonelli was ordered to drop everything and finish the documentation for the canonization of Pius X, and was not to return to Rome for any reason whatsoever until he had finished his task. As a result, it took Antonelli just under three months to complete the necessary work for the canonization of Pius X. In the book Pascalina relates the story to Murr and laughs that it was Pius X’s fifth miracle, as he was canonized in 1954, the same year Pius IX’s cause was reopened. This kind of fast moving canonization was unprecedented at the time.

Pascalina tells of Pius XII’s heroics during World War II and his efforts to help the Roman people and save the Jews from the Nazis (exploding the calumny against him). Pascalina relates:

“[W]hen the war was finally over, Dank sei Gott [praise God], the Jews of Rome were first to proclaim the Holy Father ‘Defensor Civitatis’[Defender of the City.]”

She went on to say how the Roman Jews rebuilt the Pope’s Castel Gandolfo summer residence, a token of their gratitude to him for having opened its doors to 3,000 Jews during the Nazi occupation of Rome; how he was declared a Righteous Gentile by Golda Meir, for his countless and tireless efforts in saving European Jews during the ten years of Nazi domination, and how the chief rabbi of Rome, Rabbi Israel Zolli and his entire family, having witnessed and benefited from such authentic Christian charity, converted to Catholicism.

“…And do you know what the dear rabbi chose for his baptismal name?” she asked with a big smile on her once again placid face…“A Jew with one magnificent baptismal name! Can you guess what it was, Don Carlo?”

“What was it?”

“Eugenio,” she said simply, crossed her arms and smiled (155).

Throughout the book the mutual admiration for Eugenio Pacelli—Pius XII—is shown as the story progresses through conversations about the days before Vatican II through to John XIII and Paul VI. She tells how Pius XII discovered Monsignor Montini (the future Paul VI) secretly meeting with Communists and demoted him to Milan without being given the Cardinal’s hat. They discuss Paul VI (who was the reigning pope during their conversations) and how his naivete underestimated the Church’s enemies that allowed the threat to grow within the Vatican itself, in persons like Annibale Bugnini and Sebastiano Baggio. Pascalina laments:

“The Monsignore [Montini] was never able to admit that the Church had enemies. He always thought that, if you could just sit down with everyone and talk things out, that the world and the Church would be at peace with each other. He never could see the obvious. The Church has enemies! The Church has always had enemies and the Church always will have enemies. He never saw it. How dangerous it is to have such a man in charge of things (216).”

One of the most fascinating stories shared is that of the little-known Cardinal Edouard Gagnon (1918-2007), whom Murr knew personally and acted as his assistant. Murr describes him as “a man of God, of deep faith. Intelligent and honest…A clear thinker…Not afraid of criticism…A staunch defender of Humanae Vitae” (214). Just as Benedict XVI initiated an investigation into Vatican corruption in his time (associated with the Vati-leaks scandal), so too did Paul VI initiate the same kind of investigation and called upon Gagnon to complete it. This was publicly reported on and there was great anticipation as Gagnon slowly completed an investigation which took a number of years. Meanwhile his residence and office were broken into while those guilty searched to destroy the evidence and also threatened his life.

This investigation was completed while Pascalina and Murr were both living in Rome. During this time Pascalina spoke to Gagnon and warned him about Paul VI that he “will not take any action on the findings of the investigation that he himself called for to rid the Church of that ‘Satanic smoke that has entered the temple of God.’ Papa Montini will do absolutely nothing. He will not act” (216).

Shortly after this, Pascalina’s words were proved true as Murr drove Gagnon to Paul VI to deliver the investigation of Vatican corruption. Just as the Cardinals would do with Benedict XVI decades later, Gagnon delivered his dossier to Paul VI, detailing the horror of the corruption that was at that time gripping the Vatican. And like Benedict, Pope Paul refused to act but left the whole matter to his successor, then died in 1978, leaving the dossier to pass to John Paul I, and then John Paul II. Murr then relates how Gagnon pleaded with a reluctant John Paul II to eradicate the corruption but only after years did John Paul II agree to act. (Gagnon was later chosen to investigate Marcel Lefebvre at the Society of St. Pius X as well.)

The book is a reminder to faithful Catholics that the corruption goes deep and goes back years. But it also shows the incredible journey of a good seminarian from the 1970s who was blessed with a generational connection to the pre-Vatican II Church in the person of his godmother, Madre Pacalina. Murr shows convincingly that although the darkness we are facing is intense, the saints will still face death with a smile and say, Viva Christo Rey! This book is really a celebration of Christ in the midst of woe, and as such it deserves a reading from faithful Catholics who seek to be honest about the corruption without losing hope. Murr has given the Church a rare look at a great woman of God and the crisis from her perspective. Her wit, candor and faith are graces to be shared, for which Murr should be thanked.

1 thought on “Book Review: The Godmother: Madre Pascalina, a Feminine Tour de Force”