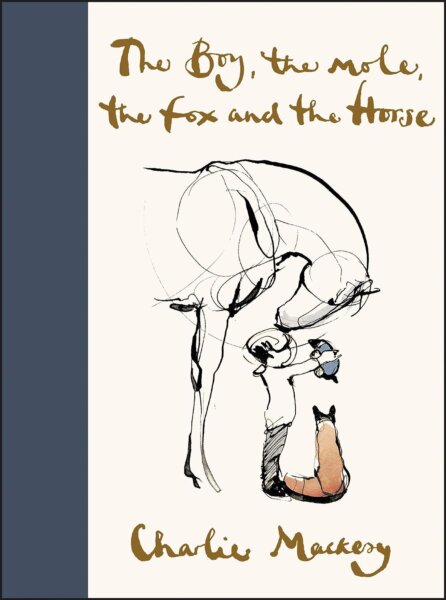

Above: Pen and watercolour of a Charlie Mackesy sketch by Daran Tate

I was sitting in a blue armchair, reading under the yellow light of a standing lamp one evening. A difficult experience and change of pace in life was just past me; with an international move behind me and new friends, new work, new ideas for my future ahead, the book I held in my hands would aid in a gentle, but real, way taking new bearings in my life. I was trying to orient myself towards a new meaning of—and search for—home.

I started at the beginning of the book, only to read: “Hello. You started at the beginning, which is impressive.” The blobby handwriting reproduced in the pages, along with sketchy scribbles had already told me this was not an ordinary book.

The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse is a picture book of mystical profundity. It is perhaps the second spirituality “picture book” that I have come across in my life. The other was The Life of Little Saint Placid. Or perhaps it would be better to say “picture book philosophy,” a refreshing echo of scripture and natural law principles from another source than the Gospels or Plato.

Written and illustrated by Charlie Mackesy, a British artist, this whimsical story—with barely a plot—follows a boy looking for his home and a mole looking for cake. Along the way they meet a fox and horse. “The boy is full of questions,” the author says in his preface. “The fox is mainly silent and wary because he’s been hurt by life.”

To call this book a lovely example of how close a seemingly secular vision of love and friendship can take you to Christian charity sounds trite. Yet a quiet openness to the genuine profundity of the drawings and simple phrases allows one to become open to a simple, natural, and refreshing experience of “love as the meaning of life.” Mackesy’s characters are timid and brave, lonely and longing for friendship and love.

This book’s strength is also its weakness: either you find it trite or profound. It is certainly adjacent to Whinnie the Pooh, only more serious. Some reviewers complained that there was no storyline. I believe that is beside the point; there is hardly any storyline because the sentiments expressed by the characters are “mid-life” sentiments: they result from uncertainties that can occur in the midst of any life regardless of plot. “Most of the old moles I know wish they had listened less to their fears and more to their dreams.”

The characters all have different strengths and weaknesses. Their differences are each other’s joy—not least when the mole chews through the wire that has trapped the fox, beginning a friendship with what would otherwise have been the mole’s predator. This is not a syllogistic manual of philosophy: but it asks the same questions and results in answers similar to those of Aristotle, St Thomas Aquinas—or even Gospel sayings. For example, the fact that it is odd that “we can only see our outsides, but nearly everything happens on the inside” seems “scripture adjacent,” the secular echo of “It is not what goes into the mouth of a man that makes him unclean and defiled, but what comes out of the mouth; this makes a man unclean and defiles (Mat. 15:11)

The British philosopher Rodger Sruton commented in his 2009 documentary Why Beauty Matters, that “Philosophers have argued that through the pursuit of beauty we shape the world as a home.” One of Mackesy’s burdens is to address the question and mystery of “home,” and its relation to security and love. The boy says that sometimes he feels lost. But the mole replies that “we love you, and love brings you home.” As they travel over the moors, through water and wind and cold dawns, the search for home leads them to conclude that “home isn’t always a place.” You can scoff at him when he says, “I think everyone is just trying to get home”—or you can see the shadow of universal desire for paradise etched on the heart of a Northumbrian cartoonist.

Looking at Mackesy’s website I stumbled across a beautiful series of sketches for a prodigal son piece. I think Mackesy portrays the delight and wordless significance of the hug better than any other artist I’ve ever seen. The mole himself discovers something better than cake: “A hug. It lasts longer.”

All the characters make various discoveries about love and friendship—not in analytical terms but intuitive ones. “Love doesn’t need you to be extraordinary.” “Life is difficult but you are loved.” The fact that the other three characters “know all about” the boy makes them love him all the more. This leads him to reflect that “sometimes I think you believe in me more than I do.” “You’ll catch up,” says the horse. “We love because he first loved us,” the Apostle John tells us. Trying to “catch up” with the love God has for us can be difficult—and perhaps hearing it from the horse will make us more open to hearing it from the one who chides us for being of “little faith.”

“Everyone is a bit scared, but we are less scared together,” says the strong and reassuring horse, who despite his size and strength (and secret power which I leave to you to discover), still acknowledges that the bravest thing he ever did in his live was to ask for help. This is because “asking for help isn’t giving up, it’s refusing to give up.” Is this not what we do in the “Our Father,” refuse to give up by asking for help? Is this not the secret of prayer in general?

“What do you think success is?” the boy asks, and the mole replies, “to love.” Be that as it may (and I think it one of the profounder sentiments the book invites us to consider), Mackesy’s book has been incredibly “successful,” having sold over eight million copies worldwide and released as a short animated film. The hundred and twenty thousand reviews on Amazon coming out at 4.8 stars attest to its popularity.

Mackesy is an artist who started his career as a cartoonist. He works in a number of media, and there is an attentive quality to his work which belies the atmospheric and sometimes semi-abstract aura they often convey. Throughout The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse, Mackesy switches mediums and page formats; sometimes it is loose ink sketches, other times detailed pen drawings, or atmospheric watercolor spreads. Sometimes monochrome, sometimes colorful, the art on one page is cozily cute, then breathtakingly serious on the next.

This bestselling book, then, is in many ways a rephrasing of many Scripture-like principles. Life-long Christian readers like myself might need to hear these truths again in a new mode; unbelievers not yet ready for Scripture or other spiritual writings might become more open to these truths presented in a non-religious context. Either way, Makesy’s book has great potential both for gifting and personal reading. If The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse is pooh-poohed as saccharin platitudes, however, I would simply recommend the mole’s favorite advice: “If at first you don’t succeed, have some cake.”