Recently I was walking through a college campus with my young son on my way to a Latin Mass. As we walked we saw a large modern “art” sculpture lifting itself from the earth. It was an abstract form of chaos made of metal with bright colors. It contorted in every direction as if the elements of metal themselves were struggling to be free of this ugly formlessness.

I turned to my son and drew his attention to the piece of metal. I pointed and said to him “That, son, is ugly.” I helped him repeat the words and correspond the word to the sight. I believed he could sense the meaning of the word even if he was younger than the age of reason. It is crucially important that my son understands the difference between beauty and ugliness. I have a duty to inculcate his sense of true beauty, so that he can be led to contemplation, instead of this profane chaos. But let me return to this in a moment.

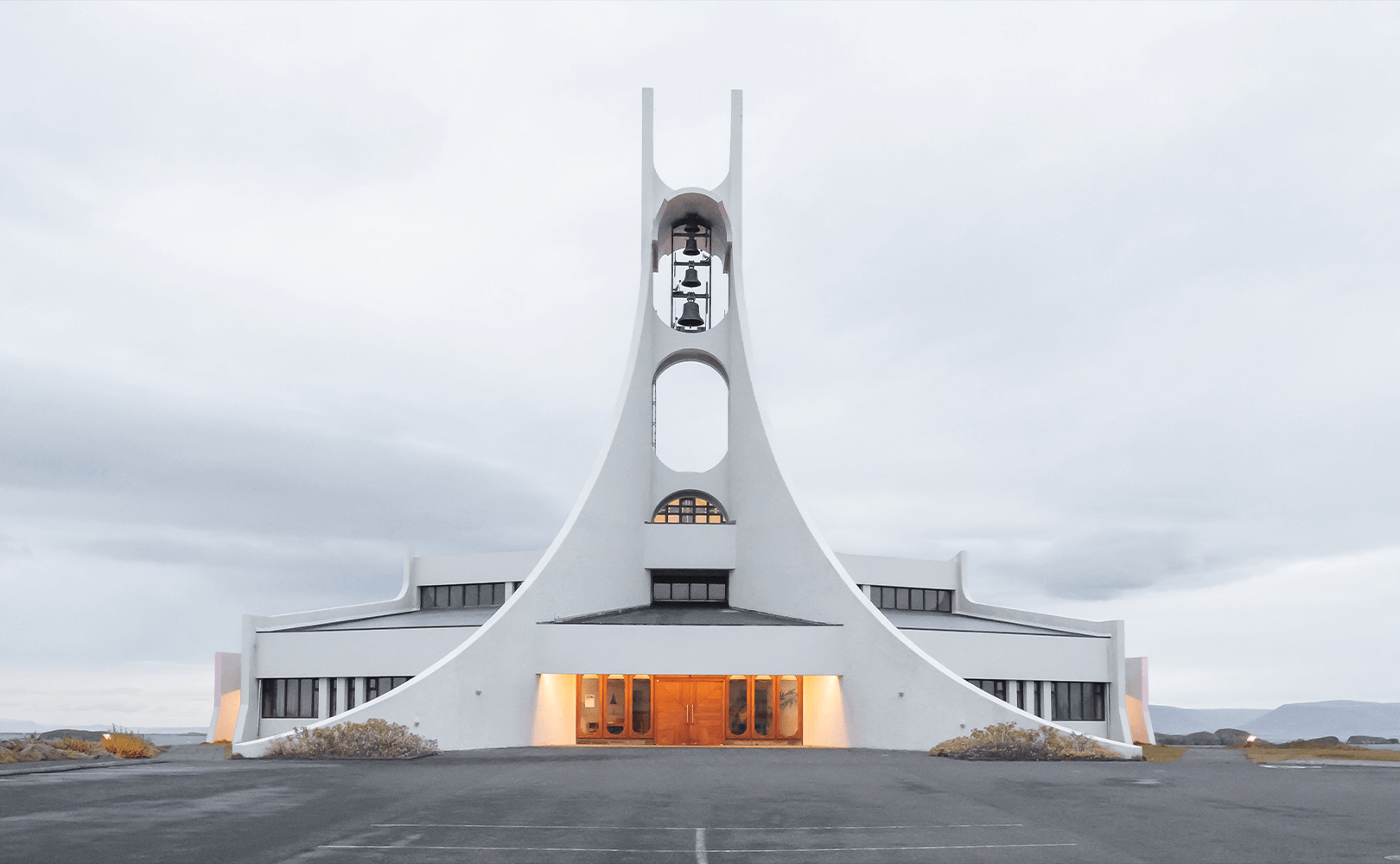

Let us consider another example, this time a sacred space where the tabernacle of the Lord of Hosts rests with His Real Presence. We’ve all seen it. It’s the sort of church that is in the shape of a large rectangle. It has the architectural ambience of a repurposed industrial building. From the outside, we see a flat roof, and maybe some triangular accents scattered about. Inside, surrounding the metaphysical grandeur of the Blessed Sacrament, we are offered a testament to banality. It’s all soft edges and theatre seating “in the round.” A plain table stands at the center, beneath banners that may as well have been designed while listening to Simon and Garfunkle and meditating on Muppets. The overall effect is reminiscent of food without seasoning: it’s bland and boring. It may not be explicitly ugly, but the absence of beauty is striking. It’s overwhelmingly ordinary, and the effect still manages to be underwhelming.

In this setting, my son has nothing to draw his senses — and thus, his mind — to the metaphysical reality of the Real Presence. I have to teach a four-year-old how to think abstractly if I want any hope of him of reversing the inclinations of this aesthetic. He knows that Jesus is up in the sky. But when he looks into the sky he feels wonder. When he looks at this rectangle theatre building, he wishes he brought his toys.

We have all seen the ugliness of modern “art,” and the banality of modern Church architecture. Perhaps we have also had the blessing of seeing beauty.

I remember the first moment I walked inside St. John Cantius in Chicago. The walls rose high into the air, communicating the transcendence of the Real Presence. The altar was raised apart, mystically showing the distance that the God-man traversed for my salvation. The reredos was adorned with an ornate order which lifted my sense beyond sight. The columns stood like monuments of faith breathing an unchanging truth.

At the sight of such beauty all thoughts evaporate. The mind is humbled. Suddenly the only thing that makes sense is to fall on your knees. There is something here that my son might understand. There is something beyond words here. There is a mystery of truth communicated by beauty which reflects the divine. “Beauty is a reflection of God,” says von Hildebrand, “a reflection of His own infinite beauty[.]”[1] It is the Logos, the tranquility of order present in a universe spoken into being. Thus St. Thomas, quoting Dionysius, elaborates that “beauty or comeliness results from the concurrence of clarity and due proportion,” and thus “God is said to be beautiful, as being ‘the cause of the harmony and clarity of the universe’” (II-II q145 a2).

St. Thomas says that beauty is an aspect of goodness, which itself is an aspect of being itself. But whereas goodness is that which is desirable in general to the appetite (like good food for instance), the beautiful is that which is desirable as “something pleasant to apprehend” (I-II q27 a1 ad3).

The beautiful is the same as the good, and they differ in aspect only. For since good is what all seek, the notion of good is that which calms the desire; while the notion of the beautiful is that which calms the desire, by being seen or known. Consequently, those senses chiefly regard the beautiful, which are the most cognitive, viz. sight and hearing, as ministering to reason (I-II q27 a1 ad3).

This is why beauty lifts the mind. This is why beauty inculcates a sense of wonder and reverence. This is something that a child can understand because a child can wonder. “Reverence,” says Von Hildebrand, “is a response to being itself.”[2] Beauty in art and architecture is a meditation of the Logos by Whom God made all things (Jn 1:3). The reverence we give to what God has made is reflected by creating beauty. O Lord our Lord, how admirable is thy name in all the earth! For thy magnificence is elevated above the heavens (Ps. 8:1). To thee, O God, I will sing a new canticle (Ps. 143:9).

The modern world, having rejected Truth Himself, worships only the will. Its art is a testament to man’s attempt to impose his will upon reality itself. There is no reverence in the twisted metal chaos on a college campus or the flat roof of a modern parish “community.” As Jones observes, the flat roof is “the main expression of the modern’s anti-transcendental attitude.”[3] In place of the beauty of holiness is the ugliness of desecration, as Scruton notes:

Desecration is a kind of defense against the sacred, an attempt to destroy its claims. In the presence of sacred things our lives are judged and in order to escape that judgement we destroy the thing that seems to accuse us.[4]

We see this stampede for ugliness playing itself out in our streets. It is what Satanist Aleister Crowley worshipped as “Thelema”—the will of man against the will of God. In other circles this pride masquerades as “freedom.” Only by desecrating the beauty of nature can man exalt his own will against the Almighty. Only by creating ugliness can man reject the Logos in Whose Image he is made. If he wishes to say non serviam, he must mutilate himself of his reason.

This is why my son must know and recognize ugliness when he sees it. He must look aghast at the disordered art, just as he must be repulsed by the disorder of evil. We must walk past this cacophony and enter the silence of the Latin Mass. Here, at the ancient Roman rite, he can see what is unseen, and hear what is unheard. For beauty leads to reverence, and reverence leads to contemplation. This is the foundation of charity, uniting the soul to God. In beauty God lifts the heart to adoration. In beauty, man offers his heart to God. “How lovely are thy tabernacles, O Lord of hosts! my soul longeth and fainteth for the courts of the Lord. My heart and my flesh have rejoiced in the living God.” (Ps. 83:2-3)

This is the gift that beauty gives, which must be passed to the next generation.

NOTES:

[1] Dietrich von Hildebrand, Aesthetics, vol. I, translated by Fr. Brian McNeil (The Hildebrand Project: 2016), 2

[2] Dietrich von Hildebrand, The Charitable Anathema (Roman Catholic Books: 1993), 37

[3] E. Michael Jones, Living Machines: Modern Architecture and the Rationalization of Sexual Misbehavior (Fidelity Press: 2012), 51

[4] Roger Scruton, Beauty: a Very Short Introduction (Oxford: 2011), 147