In a previous essay, I introduced an approach to dress that I call the School of Normalcy. I will now further explore the problems with this school of thought so widely held by Catholics today. For brevity, I have kept the focus on women’s dress. However, I believe my observations and analysis may benefit both sexes.

What is the School of Normalcy?

The School of Normalcy promotes “normal” or “relevant” modes of dress on the grounds that 1) these modes can be worthy and attractive, and 2) that they will help to integrate their wearers into modern society for the better glorification of God. Its adherents are usually conservative Catholics who, on the one hand, understand the profound significance of clothing, but who, on the other hand, cling to the notion that they can be “modern” and “integrated” rather than “frumpy, prudish, or just plain odd” like some of their Catholic brethren. Clad in hoodies and jeans, drab pants suits, or sweet sleeveless sundresses, they see themselves as under-cover agents expertly disseminating the faith in universities, the office, and Starbucks.

Their approach, they argue, differs little from that of the saints throughout history who have embraced current modes of dress and saved souls along the way: Louis IX looked like a medieval king, Margaret Clitherow like an Elizabethan housewife, Thérèse (pre-Carmel) like a daughter of the Belle Époque’s petite bourgeoisie, and so on; they all became saints, the School of Normalcy’s disciples point out; we may do the same.

Problems Beneath the Surface

On the surface, this school seems fairly reasonable. However, underneath its appealing façade, it hides some imposing problems.

First, the School of Normalcy is not historically honest. It implicitly holds that, with regard to dress, one historical period is essentially the same as the next. The school will readily admit our ancestors dressed differently, but far be it from them to hint that our ancestors dressed better. The school’s adherents do not acknowledge that we do not exist on the same historical continuum as most of the saints they hold as models.

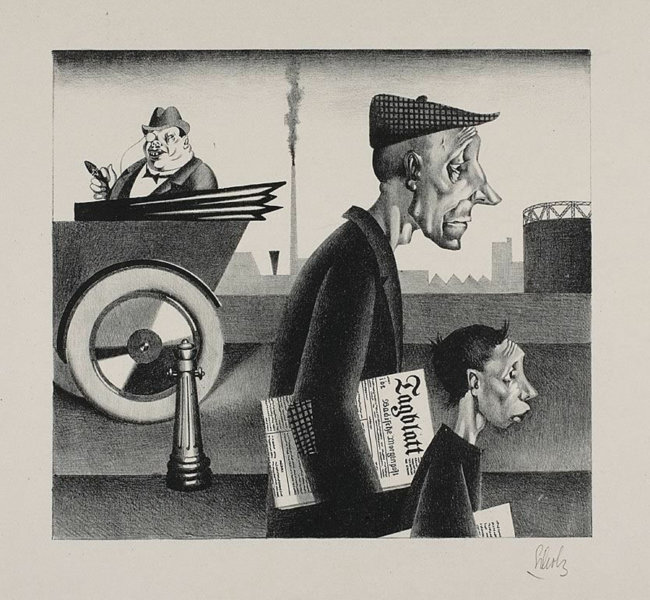

Yet, even secular commentators admit that an enormous cultural rupture took place during the First World War. This rupture had a devastating impact on all of the arts. As Reed Johnson relates in a Los Angeles Times article,

During and after World War I, flowery Victorian language was blown apart and replaced by more sinewy and R-rated prose styles. In visual art, Surrealists and Expressionists devised wobbly, chopped-up perspectives and nightmarish visions of fractured human bodies and splintered societies slouching toward moral chaos… Cynicism toward the ruling classes and disgust with war planners and profiteers led to demands for art forms that were honest and direct, less embroidered with rhetoric and euphemism.[1]

With this cynicism came profound scorn for all that was deemed romantic, sentimental, and frivolous; utility was God.

Dress and Industrialization

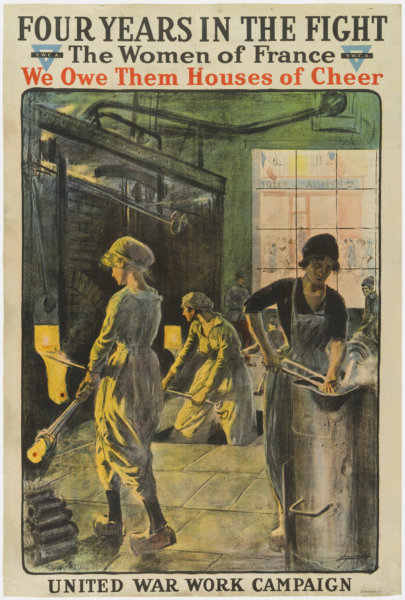

Applied arts such as dress were no longer recognized as arts at all, with the emphasis on wartime utility stifling all thought of aesthetical value. Hannah Stamler writes, “in a brief span of four years, women’s fashion went from frivolous to functional,” which underscores both the suddenness of the change and the prevailing bias held by secularists then and now—namely, that ornamented, less “functional” dress is merely frivolous (or even, as many claim, suppressive) and begging for radical change.[2]

Now, some may point to particular sartorial successes which followed the World Wars—for instance, stunning costumes of Hollywood’s Golden Age or the everyday elegance of white gloves and pillbox hats—but these were not so much a revitalization of dress as wistful echoes of better days. The drastic changes to dress that spewed forth from the sexual revolution in the sixties were merely the death rattle of something that had begun much earlier.[3]

In his Aesthetics, Catholic philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand actually puts the moment of rupture a bit prior to the Great War:

[U]ntil the beginning of the nineteenth century and the triumph of the machine, culture had not yet been strangled by civilization… Practical life as a whole possessed an organic character and was therefore united to a special poetry of life. Related to this was the penetration of life by culture. But as the practical life of the human being was robbed of its organic character and was mechanized and thereby depersonalized, so too the poetry of practical life was lost.[4]

As an illustration, one might think of Tolkien’s idyllic shire, peopled by those who “did not understand or like machines more complicated than a forge-bellows, a water-mill, or a hand-loom” verses the hellish city of Isengard controlled by Saruman’s “mind of metal and wheels.”[5]

With these considerations, should we not pause before adopting the modes of a civilization that has strangled culture? Can we, like the School of Normalcy, turn a blind eye to historical fact and pretend as if the art of dress has ambled along the avenues of time unscathed by post-Industrial ideologies? Would the saints who have gone before us, the ones who chopped down the Druids’ trees and overturned pagan altars, actually have recommended this approach? The School of Normalcy never acknowledges these questions, much less addresses them.

The Catholic View of Beauty

The next problem with the School of Normalcy is its failure to recognize beauty as an objective and crucial component in the art of dress. With scores of cloying platitudes, it assures women that they are beautiful inside and out, and they must simply discover their “personal style” to live as integrated, authentic Catholic women. One may search reams of blog entries and turn the pages of several recently published books and still come away uncertain of what actually constitutes beautiful dress.

Of course, women are beautiful. All people, even apparently homely ones, have beauty by means of their ontological dignity and, if they are virtuous, by means of their holiness. But this notwithstanding, the domain of beauty that actually pertains to the art of dress is another thing altogether.[6]

Ontological and spiritual beauty do not guarantee visible beauty. A person with a beautiful soul may have a homely face and wear hideous clothing. However, it is certainly fitting and right that the children of God seek to wear visibly beautiful clothing not only as a sign of respect for their own visible bodies (homely or not), but as a wordless way to speak of and be in harmony with their invisible beauties. It is, presumably, the duty of Catholic writers on dress to guide their readers to beautiful clothing with instruction grounded on aesthetic principles and a true philosophical understanding of beauty. Unfortunately, the School of Normalcy possesses no such principles or understanding.

Our Ancestors and Beauty

Returning again to historical considerations, I would like to point out the amazing intuition that guided our ancestors (mostly poor and illiterate) to produce truly beautiful clothing. Without much talk of aesthetics (certainly hardly any at all in the Medieval period), they somehow managed to produce wonderful works of art in all fields, not the least dress. From the charm of peasant dress to the stunning achievements of Renaissance textiles, it would seem that the air they breathed fueled the growth of the art of dress. For all of their wars, famines, plagues, and scarcity, a guiding force silently elevated their dress in a way that we, in the era of comfort, utility, and mass production can hardly fathom.

For us today, dress is not an art that grows up organically from the homes and small towns of Christendom. Rather, it hurtles down on us from the ideological towers of nameless oligarchs. We seem to have no choice but to accept formless, “gender neutral” cuts, sloppy wrinkle-proof ease, tawdry prints, and sensual second-skin loungewear. One may see this attire on full display not only in any airport, sports venue, or gas station, but in most restaurants, schools, and churches as well. And in an entirely new phenomenon, the very wealthy often appear ugliest of all. It is a kind of mass aesthetical perversion.

But as beings made in the image and likeness of God, we must seek to reflect the all-beautiful God. Men and women arrayed in ugly clothing (even with the best intentions) generate an illusion, an obstruction to the truth about who we are; this cannot but harm our own souls and thwart evangelization.

Why Do So Few Catholics Value Beauty in Dress?

One may still pause to ask why, if beauty in dress is so desirable and its lack so deplorable, more Catholics do not awaken to the flaws of contemporary dress. Indeed, it seems that even the most devout Catholics take no offense at the absence of beauty in their attire and hold little longing for any improvement. Hildebrand comments on this perplexing atrophy of aesthetic sensitivity:

People have grown accustomed to the elimination of the poetry of the world, to the mechanization of life, to the expulsion of beauty; but this does not make any less real the influence on human happiness of this destruction of the charm of an organic, truly human life.[7]

Given the prevalence of clothing—after all, every man, woman and child must dress daily—is it not very likely that the ugliness of our clothes contributes in a great measure to the malaise of our present day? The School of Normalcy’s failure to acknowledge the lack of beauty in contemporary dress, and its students’ apparent obliviousness to this omission, only proves how dire the situation has become.

Modern Beauty Not Modernistic Beauty

But surely, one may interject, the greatest appeal of the School of Normalcy among well-meaning Catholics is not so much a desire to fit in, and still less a desire to give up on beauty, but rather, a desire to simply come to peace with the conditions into which God has placed us. After all, we were born in this era and we have to wear something.

Of course, these are valid points. The problem arises when the desire for peace turns into passive acceptance and a blind promotion of modernity and relevance as if they are, in themselves, goods. As if, in the realm of aesthetics, our era is not markedly different from previous eras. As if we do not have an urgent duty to fight against the destructive spirit of our age that would make the world ever more hideous.[8] The saints we hold as models clung to the good, the true, and the beautiful.

Undeniably, we all have to bear with contemporary dress to one degree or another, but we must recognize that we are “bearing with” and not “embracing,” and in doing so, position ourselves to jump on every opportunity to improve matters. It is not vanity or snobbishness to hold that we do not dress as we ought and to go out of our way for better clothing when we can. It is sanity. If we never admit that we have taken a wrong road, we will never turn and find the right road.[9]

While we will not likely see the beauty of Medieval court dress, or the charm of traditional folk costumes, or even the relatively subdued elegance of the Edwardians restored in our lifetime, we may still plant seeds for restoration in subsequent generations. This does not mean that we should cherry-pick one “perfect” mode from history and seek to recreate that. In a discussion of architecture that applies equally well to the art of dress, Hildebrand writes:

It is indeed meaningful to say that the architect should not imitate any new style of earlier periods. But at the same time, we must explicitly emphasize that the true artist should pay no head at all to the zeitgeist. He should create a building in which the general artistic requirements are fully satisfied. He can employ many motifs, including those from earlier periods, but these will be inserted completely into the special invention of the specific building.[10]

With regard to dress, we need not make ourselves historical re-enactors, but we must certainly learn from our forebears. We can and should seek quality over quantity, embrace greater formality, and prioritize tasteful ornamentation over utility.[11]

How to Restore Beauty in Dress

We must remember that dress is an art and true art grows organically.[12] This, rather than daunting us, should actually bring us peace—and patience. Living as we do in a kind of cultural ground zero, our primary task is to clear rubble (e.g., get rid of ugly clothes) and cultivate soil for future growth.

Cultivating involves an entire re-evaluation of our way of life. First, we should ask ourselves how we worship God. Is the liturgy we attend a source of beauty that draws us up to God and reveals His majesty? Is it something that can, from its supreme height, trickle down through every aspect of our lives? Or is it a horizontal plane on which we can see nothing but ourselves and the drab gray of our own exile?

And do we have time for leisure in which we might embrace our God-given creativity, that quality that sets us apart from all other creatures and sets us so amazingly close to Him? Or do we fill our time with the cheap distractions of television and social media? If we don’t know how to make a simple greeting card for a friend or arrange a small vase of flowers, it’s unlikely we’ll ever learn much about how to satisfy the “general artistic requirements” of the art of dress.

We must, above all, be ready to sacrifice. The work of restoration is a daily cross and a stripping away of ease, of comfort, and of the consolation of having a “normal” life. Yet it will bring a new richness: our God is generous, and He will not despise our efforts. As sacred artist Gwyneth Thomson-Briggs puts it:

[A]ny time I’ve consented to pick up a cross of beauty and carry it, the sacrifice has expanded my love and brought great joy.[13]

May we now and always pick up our crosses of beauty and follow Our Lord, the source of all love and joy.

[1] Reed Johnson, “Art forever changed by World War I,” Los Angeles Times (21 July 2012).

[2] Hannah Stamler, “In Pictures: How World War I Changed Women’s Fashion,” Frieze, (19 November, 2019).

[3] Linda Przybyszewski, The Lost Art of Dress (New York, New York: Basic Books, 2014) 191-192.

[4] Dietrich von Hildebrand, Aesthetics, trans. Brian McNeil (Steubenville, Ohio: Hildebrand Project, 2018), vol. II, 52.

[5] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994), 1, 462.

[6] Dietrich von Hildebrand Aesthetics, trans. Brian McNeil (Steubenville, Ohio: Hildebrand Project, 2018), vol. I, 75-101.

[7] Ibid., 4.

[8] Ibid., vol. II, 65-66. Here, Hildebrand emphasizes the urgent educational and task of architecture, and one can easily see the same ideas applied to dress. “Architecture is not only an expression of a living cultural world. It also has the eminent educational task today of liberating the zeitgeist from its barren depoeticization and mechanization… This is why the task of contemporary architecture is very different from that in epochs in which the poetry of life still developed without hindrance and a rich cultural world filled their inner space. Today architecture must fight against the zeitgeist, not through imitation of older styles, but through unchecked use of great architectural inventions of the past, in order to create something new that is nourished by the artistic inspiration of the architect—but not by the zeitgeist.”

[9] C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (Internet Archive, 2014).

[10] Hildebrand, op. cit., vol. II, 65.

[11] To list in detail the many possible ways of restoring beauty to the art of dress, is beyond the scope of this essay but I hope to write about this later.

[12] Ibid., 8-9.

[13] Fr. Michael Rennier quoting Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs, “Starting today, here’s how to make your life more beautiful,” Aleteia (20 February 2022).