|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

As ancient is this hostelry

– Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “Prelude,” Tales of a Wayside Inn

As any in the land may be,

Built in the old Colonial day,

When men lived in a grander way,

With ampler hospitality;

If there is anything that really marks out our present era, it is pettiness – small-mindedness. One thinks immediately, of course, of the campaign against the Tridentine Mass on the part of many in the Catholic hierarchy. The torture in which so many prelates seem to delight ranges from closing down long-established Latin Mass communities to banishing that Mass from churches to gymnasia. This puerile nastiness echoes the never-ending stream of insults which the Holy Father appears to delight in, from “pickle-faced” to “coprophages.”

Apart from the annoyance of being the object of such attentions, of course, there is the shock of seeing such behaviour on the part of occupants of such elevated offices. It is also why, despite this Pontificate’s frequent exercises of power, it seems so second-rate. It has certainly generated no great artwork, no great music, and thus far, anyway, no great Saints. Diocese after diocese is guided by a policy of “managed decline,” wherein beautiful and not-so-so beautiful churches are bulldozed and the property sold. Closing and amalgamating parishes is seen as progress in this mindset.

But, of course, our secular leadership is no better. It is not just the senility of the American president and the – ah – mentally challengedness of the vice president. It is the level of intelligence and manner of behaviour demonstrated by secular leadership across the globe and in every government level. The level of political debate is very low, indeed, and bears little or no reference to the Common Good, whether it be with or between nations – it is all about “me and mine.” Thus it is difficult to come to an agreement on anything. Wokery and identity politics are nothing if not demonstrations of the most extraordinary pettiness and self-absorption. “Toning down” quasi-religious as well as purely secular civic ceremonies, from coronations to inaugurations to the openings of assemblies and city council sessions are seen as progress. Of course, given the ever-increasing silliness of so many elected officials, this may be a valid argument.

Dropping down to the mere upper classes, those who ride atop society to-day revel in being as casual and informal as possible. Of course, as we know, this is not merely about etiquette and fashion, but basic morality. Those who set the tone in society are once again all about themselves and their immediate desires. They build or create little of beauty as a consequence. One could hardly imagine to-day’s billionaires building houses of grandeur and beauty, fit and desirable to be opened as museums in a generation or two. Moreover, they are nasty toward each other, toward those who disagree with them, and to those who are dependent upon them.

There is of course as a result a great deal of pressure upon the rest of us to emulate our betters. Predictably, we follow in their lead to a greater or lesser degree, as the majority must in any human society. If social media is any gauge, we are shriller and stupider than we were before – although it may just be that we express the dumb stuff that we would not normally say in person. Like those we emulate, we tend to be ever shabbier in appearance, ever less formal. Of course, this is in the immediate aftermath of the COVID lockdown and the American hot hot summer of burning love back in 2020. From top to bottom in society to-day, pettiness triumphs, and seemingly very little has any redeeming quality. We suffer from an omnipresent and omnipotent pettiness, and a corresponding lack of greatness.

Of course, this is a complex issue. On the one hand, of course, this can be seen as a long-term process of decay, starting with the Protestant Revolt – especially in its Calvinist varieties. This revolt against the splendour of the altar led to the British Civil Wars of the 17th century, and the republican revolutions in the Americas and Europe of the 18th,, 19th, and 20th centuries, which sought to overturn the grandeur of the Throne. Since World War II, and ever more since the dawning of the 21st century there has been a revolt against age, gender, and reality itself – thus leading to the cult of the ugly, the unisexual or plurisexual, and the uniform. But it has not all been one way during that period. From time to time, as with our American presidential inaugurations, with their traditional morning coats and parades, dignity and occasionally glory reassert themselves within a given temporal and geographical context. It is not only a long process, but an ongoing battle against entropy which every generation must fight anew.

The opposite quality to pettiness is greatness, which our Greek and Latin forbears separated into two virtues: magnanimity and magnificence – both stemming from magnus, “great.” In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle defines magnanimity thusly:

Now a person is thought to be great-souled if he claims much and deserves much. He that claims less than he deserves is small-souled… For the great-souled man is justified in despising other people—his estimates are correct; but most proud men have no good ground for their pride… It is also characteristic of the great-souled man never to ask help from others, or only with reluctance, but to render aid willingly; and to be haughty towards men of position and fortune, but courteous towards those of moderate station… He must be open both in love and in hate, since concealment shows timidity; and care more for the truth than for what people will think; and speak and act openly, since as he despises other men he is outspoken and frank, except when speaking with ironical self-depreciation, as he does to common people… He does not bear a grudge, for it is not a mark of greatness of soul to recall things against people, especially the wrongs they have done you, but rather to overlook them… Such then being the Great-souled man, the corresponding character on the side of deficiency is the Small-souled man, and on that of excess the Vain man.

St. Thomas Aquinas wrote of Magnanimity in great detail in the Summa, Christianising it by adding humility and charity to its strengths:

Magnanimity by its very name denotes stretching forth of the mind to great things. Now virtue bears a relationship to two things, first to the matter about which is the field of its activity, secondly to its proper act, which consists in the right use of such matter. And since a virtuous habit is denominated chiefly from its act, a man is said to be magnanimous chiefly because he is minded to do some great act. Now an act may be called great in two ways: in one way proportionately, in another absolutely. An act may be called great proportionately, even if it consist in the use of some small or ordinary thing, if, for instance, one make a very good use of it: but an act is simply and absolutely great when it consists in the best use of the greatest thing.

From this ideal of magnanimity came the Code of Chivalry, which in turn would give birth (thanks to the Romantic Movement of the early 19th century with its rediscovery of Medieval values) the Code of the Gentleman. Mark Girouard describes it thusly:

By the end of the nineteenth century a gentleman had to be chivalrous, brave, straightforward and honourable, loyal to his monarch, country, and friends, unfailingly true to his word, ready to take issue with anyone he saw ill-treating a woman, a child, or an animal. He was a natural leader of men, and others unhesitatingly followed his lead. He was invariably gentle to the weak; above all he was always tender, respectful and courteous to women.

That this survived in the 20th century may be shown by the Emily Post’s introduction the first edition of her etiquette book:

Far more important than any mere dictum of etiquette is the fundamental code of honour, without strict observance of which no man, no matter how “polished,” can be considered a gentleman. The honour of a gentleman demands the inviolability of his word, and the incorruptibility of his principles; he is the descendant of the knight, the crusader; he is the defender of the defenseless, and the champion of justice— or he is not a gentleman.

Even in my far-off youth this was still seen as the ideal – with corresponding qualities for ladies. The Boy Scouts, the Knights of Columbus, the American Legion, and for that matter, even the school attempted to reinforce these qualities in the young; it was a battle lost by the time I entered college in 1978.

But the loss of magnanimity also led in both the historical and the immediate senses we have been exploring to that of the closely allied virtue of magnificence. In the Summa, St. Thomas explains the relationship and distinction between the two:

It belongs to magnanimity not only to tend to something great, but also to do great works in all the virtues, either by making [faciendo], or by any kind of action, as stated in Ethic. iv, 3: yet so that magnanimity, in this respect, regards the sole aspect of great, while the other virtues which, if they be perfect, do something great, direct their principal intention, not to something great, but to that which is proper to each virtue: and the greatness of the thing done is sometimes consequent upon the greatness of the virtue.

On the other hand, it belongs to magnificence not only to do something great, ‘doing’ [facere] being taken in the strict sense, but also to tend with the mind to the doing of great things. Hence Tully says (De Invent. Rhet. ii) that ‘magnificence is the discussing and administering of great and lofty undertakings, with a certain broad and noble purpose of mind, discussion’ referring to the inward intention, and ‘administration’ to the outward accomplishment. Wherefore just as magnanimity intends something great in every matter, it follows that magnificence does the same in every work that can be produced in external matter [factibili].

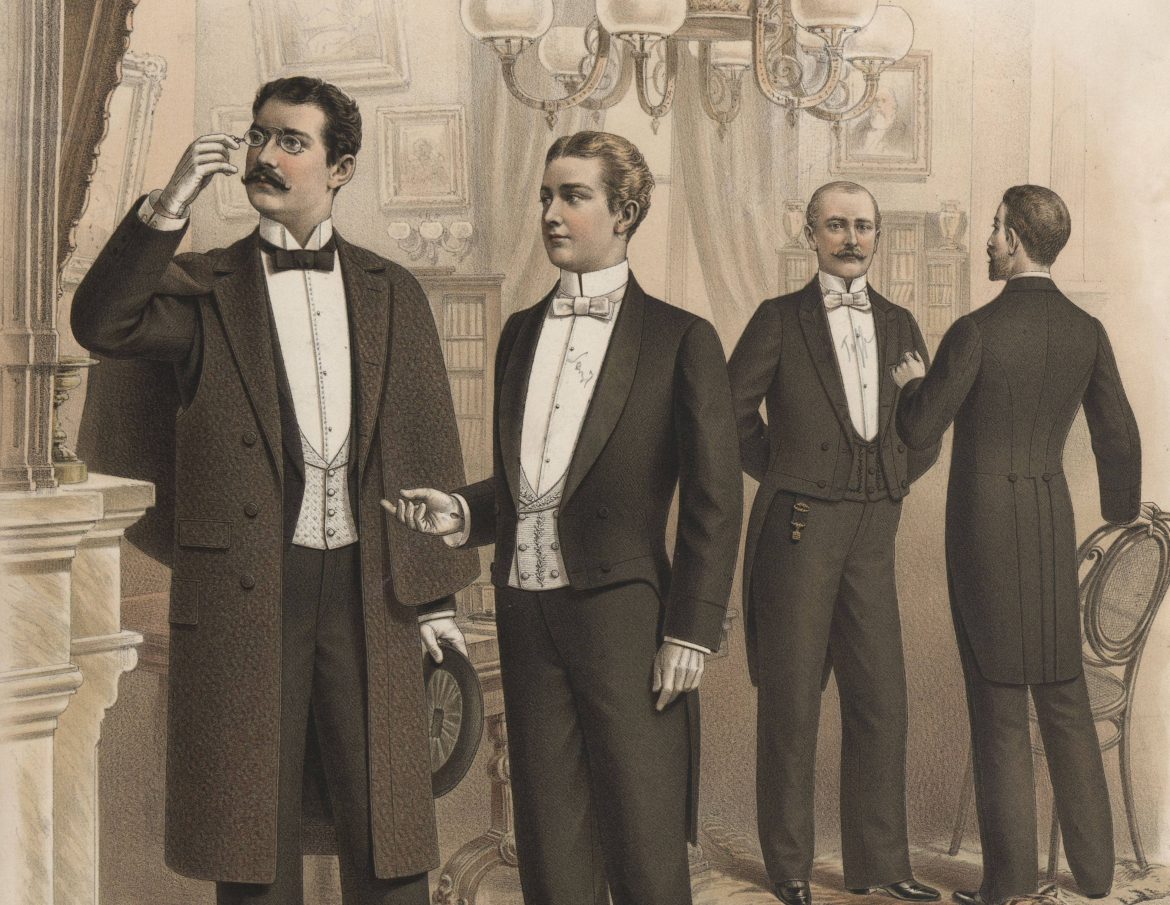

What all of this meant is that those in whom magnanimity (the highest or greatest spirit) reigns, will as a natural result attempt to do the highest or greatest thing. A gentleman will naturally and un-self-consciously act and dress well and appropriately; his home will be uplifting to himself, those with whom he dwells, and those who visit him. In those with higher responsibilities and powers, their actions and works shall also be correspondingly magnificent. The buildings they erect – churches, public buildings, libraries, hospitals, bridges, and the like – will be as magnificent as they can make them; even their homes will often enough reflect glory upon their office rather than provide for their comfort. Many a Royal Palace and noble Castle boasts impressive state and guest rooms – and rather uncomfortable master bedrooms. The ceremonials of their state in life will be carried out punctiliously – not because they bring honour to the individual, but to his office.

It is precisely the loss of magnanimity in our ecclesiastical and secular rulers that has led to the current shabbiness in Church, State, and culture. Despite the myth of equality (often enough used to destroy both magnanimity and magnificence where they have managed to hold on), man is hierarchical by nature. Our leaders create the atmosphere in which we live, and we more or less unconsciously imbibe a great deal of it, as with the air we breathe. But if we look around in disgust at what we see, we are obligated thereby to do something about it. The question is – what?

We must start with ourselves, because in truth, the space within our skulls is the only area in which most of us have any real control. We must strive to be magnanimous – not responding to petty insults, saving our rage for important things. We must think of others before ourselves, and try not to answer disagreement with ad hominem attacks, but with reasoned argument if possible, and amused disengagement if not. We must be slow to anger, and quick to forgive. We must try to learn the rules of etiquette, however antiquated they may seem, and attempt to live by them.

But them, how to be magnificent? Well, if we have limited resources, it is a question of keeping ourselves and our dwellings as clean, decent, and engaging as possible. If we have sufficient enough to make a display, it should be uplifting and elegant in a manner proportionate to what is being done – especially as regards the religious element in one’s house. But magnificence also means great deeds – and these can be praying and engaging in volunteer work for any laudable religious, political, or cultural goal, from keeping an abortion mill out of the neighbourhood to maintaining an historic house or doing time at a soup kitchen.

It might be argued that such efforts count for little in the scheme of things. No doubt: but they will make life far more pleasant for ourselves and those around us in the immediate. They also involve imitating our God who is Himself Magnanimity and Magnificence, as He showed not only by His Creation of the Cosmos, but His Incarnation in order to Redeem it. If enough of us do so, we may one day deserve and perhaps even be blessed with rulers Who resemble Him in these virtues – and others.