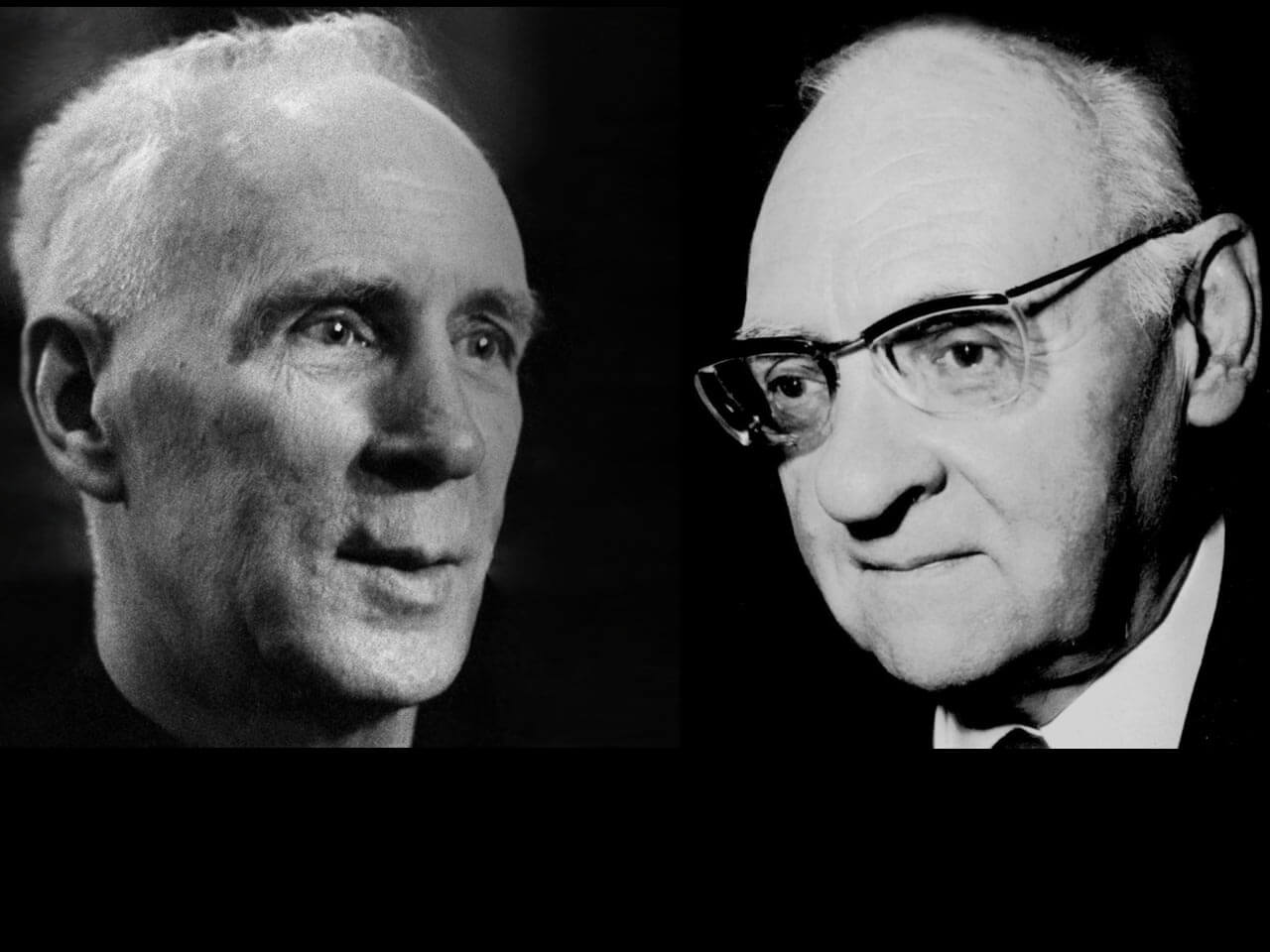

(Image: From left to right, Henri de Lubac and Hans Urs von Balthasar)

Editor’s note: The author of this essay is, according to his own words, “not a certified academic, let alone theologian. These thoughts are simply the opinion of a Catholic artist who, having studied the deprivations of ‘Modern art,’ is concerned about the current state of the Catholic Church and how the same alien, even diabolical influences seen in art, seem to have crept into the Church since the Second Vatican Council.”

As reported in the New Oxford Review online edition of February 22, 2017, the superior general of the Society of Jesus has said that all Church doctrine must be subject to discernment.

In an interview with a Swiss journalist, Father Arturo Sosa Abascal said that the words of Jesus, too, must be weighed in their “historical context,” taking into account the culture in which Jesus lived and the human limitations of the men who wrote the Gospels.

In an exchange about Church teaching on marriage and divorce, when questioned about Christ’s condemnation of adultery, Father Sosa said that “there would have to be a lot of reflection on what Jesus really said.” He continued:

At that time, no one had a recorder to take down his words. What is known is that the words of Jesus must be contextualized, they are expressed in a language, in a specific setting, they are addressed to someone in particular.

Father Sosa explained that he did not mean to question the words of Jesus, but to suggest further examination of “the word of Jesus as we have interpreted it.” He said that his new process of discernment should be guided by the Holy Spirit.

When the interviewer remarked that an individual’s discernment might lead him to a conclusion at odds with Catholic doctrine, the Jesuit superior replied: “That is so, because doctrine does not replace discernment, nor does it [replace the] Holy Spirit.”

The views held by Fr. Sosa did not spontaneously generate out of a vacuum.

At the time of the Second Vatican Council (Oct. 1962–Dec. 1965), leaving aside the traditionalists faithful to the vision of Pope Pius XII and his predecessors, the Church split between “Conservative” and “Progressive” factions led by the speculative theology of leading contemporary Catholic thinkers. The progressives, at the closing of Vatican II in 1965, began publication of a scholarly journal titled Concilium featuring the writings of Yves Congar, Hans Küng, Johann Baptist Metz, Karl Rahner S.J., and Edward Schillebeeckx. among others. In contrast, a group of the more conservative modern thinkers, including Joseph Ratzinger, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Henri de Lubac, Walter Kasper, Marc Ouellet, Louis Bouyer and others, founded a counterpart journal in 1972, called Communio.

While the writings of the progressives such as Hans Küng, Schillebeeckx, and especially Karl Rahner S.J. have had a heavy influence on contemporary Catholic thought, in order to understand the quote above by the Jesuit Superior General, one must look also to the so-called “conservative” Jesuit theologian, Henri de Lubac S.J. and the ex-Jesuit Hans Urs von Balthasar for the ultimate demolition of pre-Vatican II theology.

Henri de Lubac, who went on to be Cardinal under Pope John Paul II in 1983, had earlier come under suspicion of the pre-Vatican II authorities (Holy Office) and, although not specifically named, was known to be the promoter of the heretical ideas denounced in the encyclicals Mystici Corporis (1943) and Humani Generis[1] (1950) of Pope Pius XII.

These following words of the Pope, taken from Mystici Corporis, “There is… a false mysticism creeping in, which, in its attempt to eliminate the immovable frontier that separates creatures from the Creator that falsifies the Sacred Scriptures”[2] were directed in response to de Lubac’s yet unpublished essays; these had spread especially among his colleagues at the Jesuit Theologate, La Fourvière, and they were summed up in his controversial book, Surnaturel published in 1943. The thesis of these essays was that all men, according to their very nature, possessed one supernatural end with the graces sufficient to attain the Beatific Vision without need of the added gratuitous graces obtained through sacramental incorporation into the Mystical Body of Christ.

In June of 1950, as de Lubac himself said, “lightning struck Fourvière.”[3] He was removed from his professorship at Lyon and his editorship of Recherches de science religieuse, and he was required to leave the Lyon province. All Jesuit provincials were directed to remove three of his books – Surnaturel, Corpus Mysticum and Connaissance de Dieu – because of “pernicious errors on essential points of dogma.”

In 1962, well after the death of Pius XII, de Lubac wrote the book Teilhard de Chardin: The Man and His Meaning,[4] extolling the writings of the pantheist paleontologist whose notes he had studied along with his colleagues at La Fourvière. De Chardin himself had been censured and stripped of his teaching position already in 1925 for denying Original Sin and the existence of Hell. His writings are still officially proscribed,[5] but remain, however, immensely popular today among Jesuits and even within some of the highest ranking circles of the contemporary Roman Catholic Church.

Following the above-mentioned books, in 1979–1981 de Lubac wrote an enthusiastic book on the 12th-century monk and mystic Joachim da Fiore, entitled La Posterité Spirituelle de Joachim de Flore.

While this book, written in French, and as yet untranslated into English, remains relatively unknown to the general readership, most “conservative” commentators speak favorably of it as a denunciation of secular utopian dreams.

Joachim da Fiore’s dream was, however, anything but materialistic. His vision was that there existed a divinely inspired historical progression, as noted by the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: “From the Church visible to the Church of the spirit. From the historic Gospel to the eternal one. Not “anti-” but “trans-Catholic.”[6]

According to Joachim, salvation history was divided into three periods: the Old Testament or age of the Father with its rigorous Mosaic law; the New Testament as the age of the Son embodied in the Roman Sacramental Church founded on Peter; and a final age of the Holy Spirit, a “tempus amplioris gratiae,” a time of universal convergence and freedom from the law, symbolically identified with St. John the Evangelist, “the apostle of love.”[7]

In this vein, de Lubac’s book speaks, enigmatically but more or less favorably, of an 1884 speech to the College de France by the Polish historian of Slavonic literature (occultist Martinist and Freemason) Adam Mickiewicz, on his vision of the future Church:

“Christmas. At St. Peter’s in Rome, the Pope says Mass surrounded by tired old men. Suddenly in their midst a young man dressed in purple enters: it is the Church of the future in the person of [St.] John. He tells the pilgrims that the times are fulfilled… He calls the head of the apostles by name (Peter) and tells him to leave the tomb … (He comes forth).… The cupola of the Basilica cracks open and splits and Peter goes back into his tomb having given his place to John. The faithful pilgrims die under the ruins… Peter has died forever. The Roman Church is finished, its last faithful are dead. ….They (a group of attending Polish peasants according to Mickiewicz) shall open this cupola to the light of heaven so that it looks like that pantheon of which it is a copy: so that it may be the basilica of the universe, the pantheon, the pan cosmos and pandemic, the temple of all spirits; so that it gives us the key to all of the traditions and all of the philosophies.”[8]

“An ecumenism without boundary stones, with a total opening to the future, still within the Church of Christ, moved to enlarge itself without ceasing to be the immortal dream of remaining Catholic.”[9] (emphasis in original)

This passage clearly relates to Joachim’s historical vision, taken up by Hegel and the pantheistic Freemasons Friedrich Schelling and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing wherein, prior to the end of the world, there would be a final immanent “Age of the Holy Spirit” composed of absolute freedom wherein all would have direct access to the guidance of the “Holy Spirit” without the necessity of recourse to the doctrinal or moral teachings of Holy Mother Church.

Is this not what Fr. Sosa is proposing?

II

Among de Lubac’s younger contemporaries whom he mentored at La Fourvière was Hans Urs von Balthasar (S.J.) whom many, if not most, “conservatives” consider the foremost theologian of the post-Conciliar Church.

Having finished his seven years of training at La Fourvière, Balthasar was ordained a priest in 1936. He then worked briefly in Munich, for the Jesuit journal Stimmen der Zeit. In 1940, with the Nazi regime encroaching on the freedom of Catholic journalists, he left Germany and began work in Basel as a student chaplain.

It was there that he met the twice-married Protestant mystic, Adrienne von Speyr, whom he converted to the Catholic Faith. In 1945, they founded together a religious society called the Community of St. John to promote the visionary theology of Frau von Speyr. Due to incompatibility of doctrine, von Balthasar left the Jesuits in 1950 to continue in earnest his collaboration with von Speyr. According to Von Balthasar in his book Our Task (Il nostro compito),[10] “her work and mine are not at all separable: neither psychologically nor philologically. For they constitute both halves of a whole which has as its center a unique foundation” ….”The main goal of this book is simply to prevent any attempt of separating my work from that of Adrienne von Speyr, after my death.”

Adrienne maintained that Heaven had entrusted an ecclesiastical mission to von Balthasar and to herself. In a “Marian” vision, Adrienne says to God: “We both (Adrienne and von Balthasar) wish to love You, to serve You, and to thank You for the Church You have entrusted to us.” These last words, Adrienne continues, were uttered in an improvised manner and were dictated by the Mother of God, that is to say, by us (the Mother of God and Adrienne); “we spoke those words both of us together, and for a fraction of a second, she placed the child in my arms, but it was not only the child, it was the Una Sancta (the Church) in miniature, and seemed to me, to represent a unity of everything that has been entrusted to us and which constitutes a work in God for the Catholic [Faith].”[11]

This claim that the Blessed Mother herself had entrusted the future of the Church into their (Hans and Adrienne’s) hands, that is to say, in a private revelation, independent of the hierarchy and magisterium, is suspicious and highly irregular. That the hierarchy and magisterium should take these controversial revelations to be authentic at face value is inexplicable.[12]

Von Balthasar is best known to general audiences for his controversial 1986 book, Dare We Hope That All Men Be Saved?, which is based, in part, on the speculation of the brilliant Greek theologian Origen (185–253) whose thoughts contained in his treatise De Principiis 1.6.-3, however, on apokatastasis (universal salvation, including the devil), were condemned at the Second (5th Ecumenical) Council of Constantinople (583).[13]

In this work, von Balthasar states in his epilogue that Origen, as well as Gregory of Nyssa, and Maximus the Confessor based their circular theory of history leading to apokatastasis on neo-Platonic and Gnostic theories prevalent in the Eastern Empire at that time. He also suggests that these ideas reemerge in the works of Meister Ekhart and Teilhard de Chardin.[14]

Lesser known is his elegiac postscript (foreword in the German edition) to Valentin Tomberg’s 1985 book titled Meditations on the Tarot, a Journey into Christian Hermeticism.[15]

Lack of space prohibits a full treatment of this book, which deserves a thorough review, but there are some salient quotes that will give a quite accurate idea of the general tone of the work. The “anonymous” author, Valentin Tomberg, presents Gnosticism, Magic, Kabbalah (Cabala), and Hermeticism as not only compatible, but essential to true Catholic belief. While he quotes St. Paul and St. John the Evangelist and extols the visions of such Catholic mystics as St. John of the Cross, St. Theresa of Avila and St. Francis of Assisi, as well as quoting from St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, he gives equal coverage to Masonic Martinist Saint Yves d’Alveydre, the acknowledged Luciferian Stanislau de Guaita, the Satanic Magician Eliphas Lévi, as well as the Kabbalistic false Messiah Sabbatai Zevi, Madame Blavatsky, Swami Vivekananda, Rudolf Steiner, Teilhard de Chardin, Jacob Boehme, Swedenborg, Carl Jung, and a host of others.

Von Balthasar has nothing but praise for this work. In his foreword (in the German edition) /afterword (in the English edition), he has the following to say:

A thinking, praying Christian of unmistakable purity reveals to us the symbols of Christian Hermeticism in its various levels of mysticism, gnosis and magic, taking in also the Cabbala (Kabbalah) and certain elements of astrology and alchemy….. the so-called “secret wisdom of the Egyptians …. (emphasis added)

Professor von Balthasar continues, saying: “… However, just as strong in its creative power of transformation is the incorporation of Jacob Boehme’s Christosophy ….”

….A third, less clear-cut transposition will be referred to briefly: that of the ancient magic/alchemy into the realm of depth psychology by C.G. Jung.

….The mystical, magical, occult tributaries which flow into the stream of his (Tomberg’s) meditations are much more encompassing; yet the confluence of their waters within him, full of movement, becomes inwardly a unity of Christian contemplation. …. Repeated attempts have been made to accommodate the Cabbala and the Tarot to Catholic teaching. The most extensive undertaking of this kind was that of Élephas Lévi (the Pseudonyme of Abbé Alphonse-Louis Constant) whose first work (Dogma et ritual de la haute magie) appeared in 1854.

The list of “spiritual” seekers promoted in this glowing afterword to Tomberg’s book goes on, however, a brief introduction to some of those listed above will suffice to show their incompatibility with Catholic Faith and morals.

First off all, Jacob Boehme (1575–1624), a Bohemian shoemaker, from a Lutheran family, who – like Frau von Speyr – was subject to visions, starting in 1600 wherein he saw a great light reflected in a dark pewter plate which led him to proclaim the following:

The being of all beings is but a single being, yet in giving birth to itself, it divides itself into two principles, into light and darkness, into joy and pain, into evil and good, into love and wrath, …Creation itself as his own love-play between the qualities of both eternal desires.

(Jakob Böhme, Sämtliche Schriften ed. W. E. Peuckert, vol. 16 (Stuttgart: Frommann, 1957), p. 233.)

Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) renowned Swiss psychoanalyst, son of a pastor of the Reformed Swiss Church began hearing voices and having visions in 1913. His religious conclusions contain the following quote:

In our diagram, Christ and the devil appear as equal and opposite, thus conforming to the idea of the “adversary.” This opposition means conflict to the last; and it is the task of humanity to endure this conflict until the time or turning-point is reached where good and evil begin to relativise themselves, to doubt themselves, and the cry is roused for a morality ‘beyond good and evil’.

(Carl Gustav Jung, Zur Psychologie der Trinitätslehre, translated in vol. 11, 2nd ed. of his Complete Works (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), p. 174)

Éliphas Lévi, a.k.a. Abbé Alphonse-Louis Constant (1810–1875), French occultist, born Catholic, ex-seminarian, best known for his work Dogme et rituel de la haute magie (1854)[16]:

What is more absurd and more impious than to attribute the name of Lucifer to the devil, that is, to personified evil. The intellectual Lucifer is the spirit of intelligence and love; it is the paraclete, it is the Holy Spirit, while the physical Lucifer is the great agent of universal magnetism.

(Éliphas Lévi, The Mysteries of Magic, p. 428; emphasis added)

The created principle is [yod] the divine phallus; and the created principle is the formal [cteïs] female organ. The insertion of the vertical phallus into the horizontal cteïs forms the cross of the Gnostics, or the philosophical cross of the Freemasons.

(Éliphas Lévi, Dogme et rituel de la haute magie[17] (Paris: Chacon Frères, 1930), pp. 123-124.)

The image below signed by Lévi, with goats head, erect phallus and female breasts, is the classic depiction of Satan. [18]

All of the above authors are in agreement that to achieve universal or divine harmony, apokatastasis, there must be an interplay and unification between the forces of male and female [androgyny], light and dark, and of good and evil – God and the Devil.

This is the express doctrine of the Cabbala (Kabbalah), as promoted by both esoteric mystical Judaism and Freemasonry, and, again, as extolled above by von Balthasar. Below are two interesting references to the Cabbala, the first by the Argentine author, Jorge Luis Borges, and the second by Éliphas Lévi:

Kabbalah considers the necessity of evil, theodicy, which, along with the Gnostics, equates with an imperfect God of creation who is not the final God. …. [that is to say] the doctrine of the Greeks called apokatastasis, that all creatures, including Cain and the Devil, will return, at the end of great transmigrations, to be mingled again with the Divinity from which they once emerged.[19]

The Lucifer of the Kabbalah is not an accursed and stricken angel; he is the angel who enlightens, who regenerates by fire.[20]

Or, as Albert Pike in his authoritative Morals and Dogma of Freemasonry explains in chapter XXII “Sublime Prince of the Royal Secret”:

“The primary tradition of the single revelation has been preserved under the name of the ‘Kabalah’ (sic.)…. of that Equilibrium between Good and Evil, and Light and Darkness in the world which assures us that all is the work of the Infinite Wisdom and Infinite Love.”[21]

This “theodicy” is totally alien to orthodox Catholicism and blasphemous in the extreme, for as St. Paul warns us, not by tape recorder, but via his written instruction, “… For what fellowship hath righteousness with unrighteousness, and what communion hath light with darkness? And what concord hath Christ with Beliel?” (2 Corinthians” 6:14,15)

While the personal faith and devotion to Christ and Our Lady of Hans Urs von Balthasar are in no way to be questioned, his pantheon, deduced from the above, appears to include Lucifer/Satan and the fallen angels as necessary participants’ in the divine drama of universal salvation.

The thoughts contained in this afterword to Tomberg’s Meditations on the Tarot were written in 1985, that is to say, one year prior to the original 1986 German edition of Dare We Hope? To what extent did Tomberg’s occult theosophy influence von Balthasar’s view of salvation, and how deeply has the Cabbalistic occult doctrine of a binary God composed of both good and evil penetrated the Jesuit order as well as the Church at large?

NOTES:

[1] “ …concealed beneath the mask of virtue, there are many, who, deploring disagreement among men and intellectual confusion, through an imprudent zeal for souls, are urged by a great and ardent desire to do away with the barrier that divides good and honest men; these advocate an ‘eirenism’ according to which by setting aside the questions which divide men, they aim not only at joining forces to repel the attacks of atheism, but also at reconciling things opposed to one another in the field of dogma….today some are presumptive enough to question seriously whether theology…should not only be perfected, but also completely reformed in order to promote the more efficacious propagation of the kingdom of Christ everywhere throughout the world among men of every culture and religious opinion.” H.H. Pope Pius XII, Human Generis, 1946 art. 11

[2] H.H. Pope Pius XII, Mystici Corporis Christi, Art. 6, Vatican 1943, English translation, St. Paul Editions.

[3] Henri de Lubac, At the Service of the Church (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1993), p. 67.

[4] Henri de Lubac, La Pensée Religieuse du Père Teilhard de Chardin (Paris: Aubier, 1962), English translation: The Man and His Meaning, (New York: New American Library, 1964)

[5] Monitum: “Several works of Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, some of which were posthumously published, are being edited and are gaining a good deal of success. Prescinding from a judgment about those points that concern the positive sciences, it is sufficiently clear that the above-mentioned works abound in such ambiguities and indeed even serious errors, as to offend Catholic doctrine. For this reason, the most eminent and most revered Fathers of the Holy Office exhort all Ordinaries as well as the superiors of Religious institutes, rectors of seminaries and presidents of universities, effectively to protect the minds, particularly of the youth, against the dangers presented by the works of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin and of his followers. Given at Rome, from the palace of the Holy Office, on the thirtieth day of June, 1962. Sebastianus Masala, Notarius.”

Communiqué of the Press Office of the Holy See (appearing in the English edition of L’Osservatore Romano, July 20, 1981): “The letter sent by the Cardinal Secretary of State to His Excellency Mons. Poupard on the occasion of the centenary of the birth of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin has been interpreted in a certain section of the press as a revision of previous stands taken by the Holy See in regard to this author, and in particular of the Monitum of the Holy Office of 30 June 1962, which pointed out that the work of the author contained ambiguities and grave doctrinal errors. The question has been asked whether such an interpretation is well founded. After having consulted the Cardinal Secretary of State and the Cardinal Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which, by order of the Holy Father, had been duly consulted beforehand, about the letter in question, we are in a position to reply in the negative. Far from being a revision of the previous stands of the Holy See, Cardinal Casaroli’s letter expresses reservations in various passages – and these reservations have been passed over in silence by certain newspapers – reservations which refer precisely to the judgment given in the Monitum of June 1962, even though this document is not explicitly mentioned.”

[6] Georg W. Friedrich Hegel, quoted by Massimo Borghesi, “Joachim and his Spiritual Sons,” 30 Days, No. 3 – 1994, p. 56

[7] Ibid., “Joachim and his Spiritual Sons,” pp. 57-61

[8] Henri de Lubac, La Postérité Spirituelle de Joachim de Flore (Paris: Lethielleux, 1981), pp. 270-271

[9] Ibid., p. 275; emphasis in the original French

[10] Hans Urs von Balthasar, Our Task (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1994), p. 130

[11] Ibid., p. 51

[12] One example of von Balthasar’s and von Speyr’s theology based on the latter’s visions concerns the Catholic doctrine contained in the Creed concerning Christ’s descent to the underworld (ad inferos). Following the view of John Calvin, von Speyr maintains that Christ suffered total alienation and suffering in the Hell of the damned as distinct from the traditional Catholic view held by St. Thomas Aquinas that Christ did not enter the Hell of the dammed , but the limbo of the Just in order to release them (St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica III, 52 part ll). Another glaring contradiction is her Protestant view of the Eucharist explained in her book The Passion from Within (published in English in 1998) wherein she claims that Christ in the Eucharist becomes bread and is bread: “Having become flesh, he now becomes bread…. he gives his body to the bread.” And again, she says, “he gives to the church the act of his becoming bread as well as the state of being bread,” reiterating, “The bread is not part of his body; it is his whole body…and thus he achieves the full identity between the two forms of his body.” (pp. 24, 31, 37, cit. Ann Barbour Gardiner, New Oxford Review, Sept. 2002)

[13] Mgr. Philip Hughes, History of the Councils, http://www.christusrex.org/www1/CDHN/coun6.html

For von Balthasar, the “devil” is not save as (he-it) is not truely a person as (he-it) is not truly a person as being incapable of love.

[14] Hans Urs von Balthasar, Dare We Hope That All Men Are Saved? English translation Dr. David Kripp and Fr. Lothar Krauth (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988), Epilogue

[15] Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg), Meditations on the Tarot (New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putman, 1985)

[16] The complete text of this book in English translation by Arthur Waite is available in pdf format at: http://www.iapsop.com/ssoc/1896__levi___transcendental_magic.pdf

[17] This and more quotes may be found at: “Eliphas Levi.” AZQuotes.com. Wind and Fly LTD, 2017. 10 March 2017. http://www.azquotes.com/author/8769-Eliphas_Levi

[18] Dogme et rituel de la haute magie (1854), English translation by Arthur Waite as Transcendental Magic http://www.iapsop.com/ssoc/1896__levi___transcendental_magic.pdf (p. 174)

[19] Jorge Luis Borges, Seven Nights (New York: New Directions, 1984), cited in The University Bookman, ed. Russell Kirk, Winter 1987, p. 15, review by Anthony Kerrigan

[20] Dogme et rituel de la haute magie (1854), English translation by Arthur Waite as Transcendantal Magic (London: George Redway, 1896), p.177

[21] Albert Pike, Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Free Masonry (Charleston: Southern Jurisdiction, A\M\ 5680), pp. 841, 859