We continue our project of delving, albeit briefly, into the first reading for Sunday’s Holy Mass in the Vetus Ordo of the Roman Rite, the Epistle, this time from the Apostle to the Gentiles’ Letter to the Romans.

Reminder: the readings of Mass have their didactic purpose for spiritual and moral instruction, but they are first and foremost sacrificial offerings raised to the Father through the voice of the alter Christus … other Christ… standing at the altar of Sacrifice. This is why the readings in the Vetus Ordo are read at the altar by the priest even if they are repeated solemnly by the subdeacon and deacon or read later in the vernacular. This is why they are sung. There is a practical reason for singing. In ages without microphones the sung word carried better and could be heard and, with the melody, remembered in a time when printed materials were rarer. They are, however, sung first and foremost, because they are special, the Word of God, every syllable of which rings with the Word, the Divine Logos. Each word is Christ raising and being raised sacrificially to the Father.

As Marshal McLuhan argued (“Liturgy and the Microphone,” The Critic, 33/1 (October–December 1974): 12–17), rightly I think, with the ubiquitous impositions of microphones in our sacred liturgical rites… how’s this for a mixed metaphor… the camel’s nose got under the barn door and let the cat out of the tent flap. Keep in mind that this, also, constituted context for our Mass readings. There are now microphones. That must have an effect on the impact of the rite and, therefore, our participation in the rite and, therefore, our identity. More on that, perhaps, another time.

We have come to our 4th Sunday after Pentecost. Romans 8:18-23 is our pericope. More context.

The chapter begins with contrasts. Paul says life in the law of Christ and the Holy Spirit sets us free from the law of sin and death. Those who embrace the things of the flesh cannot please God and those who embrace the Spirit have life and peace. Those who are in the Spirit are the “sons of God.” Let us now see our reading.

I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us. For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God; for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will but by the will of him who subjected it in hope; because the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and obtain the glorious liberty of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning in travail together until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies.

Huh?

Let’s break this down. First, Paul acknowledges that there are sufferings. These result from Original Sin and the Enemy and his agents. As bad as these sufferings are, the glory to come is greater. This is a profound reason for hope. Why? The next sentence in Greek starts with gar, a particle that assigns a reason in an argument, after the definite article he for the next word apokaradokía, “earnest expectation, eager longing.” There is a mighty expectation.

Expectations don’t float around on their own. Sentient beings have expectations. What is the sentient being with this powerful longing? Greek ktísis, creation. Creation is, in this construction, a sentient being with longing for the apokálypsis, the manifestation or revealing of the “sons of God.” Why? Because earnestly longing, eager ktísis will also be liberated from the bondage of sin and death that the sons of God will experience. Ktísis, creation, is groaning (systenázo) together with the sons of God for what is to come. Ktísis is undergoing agony as if in childbirth together with us (synodíno) awaiting the revelation of the sons of God. That syn-, together, in those verbs brings together the elements of creation, old and new, and points them at what is to come.

Whew.

At the end of the world, the sons of God shall be revealed, freed from the bondage of sin and death. This is something for which we, as Christians, should earnestly desire, long for deeply. We hope for it. It is hard to see, now. We peer at it as if in a glass, darkly (1 Cor 13). Paul, however, is saying that all of creation is also peering, even straining toward that day, longing for freedom from bondage.

Remember what Christ said of material creation? In John 12:31, Christ says: “Now is the judgment of this world, now shall the ruler of this world be cast out.” In John 14:30, Christ says, “I will no longer talk much with you, for the ruler of this world is coming. He has no power over me.” Paul, in Ephesians 2:1-2, says that, “you he made alive, when you were dead through the trespasses and sins in which you once walked, following the course of this world, following the prince of the power of the air, the spirit that is now at work in the sons of disobedience.” He goes on with a similar contrast of the flesh and the spirit. In 2 Cor 4:4, Paul says, “In their case the god of this world has blinded the minds of the unbelievers, to keep them from seeing the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the likeness of God.” And back to the Johannine stream, in 1 John 5:19:

We know that we are of God, and the whole world is in the power of the evil one.

We read in the Catechism of the Catholic Church of the effects of the Original Sin of our First Parents, two of them being that the harmony of creation with man was distorted and creation came under the bondage of sin and death.

The harmony in which they had found themselves, thanks to original justice, is now destroyed: the control of the soul’s spiritual faculties over the body is shattered; the union of man and woman becomes subject to tensions, their relations henceforth marked by lust and domination. Harmony with creation is broken: visible creation has become alien and hostile to man. Because of man, creation is now subject “to its bondage to decay”. Finally, the consequence explicitly foretold for this disobedience will come true: man will “return to the ground”, for out of it he was taken. Death makes its entrance into human history.

Thus, all ktísis, groaning like a woman in labor about to receive the revealing of her child, also longs for the revelation of the sons of God in the end time. The coming of Christ into the world opened the way for us to receive the “adoption as sons” (Gal 4:4-5).

In the new creation that groans to be born we will have the Heavenly Jerusalem, God’s dwelling with men, where “he will wipe away every tear” and all “former things have passed away” (Rev 21:4).

In the summation of things, in the end, in the new creation, as the Catechism says:

The visible universe, then, is itself destined to be transformed, “so that the world itself, restored to its original state, facing no further obstacles, should be at the service of the just,” sharing their glorification in the risen Jesus Christ.

The final state will be far more glorious than even the original state before the fall. In this sense we can sing confidently and joyfully at Easter the words perhaps inspired by St. Ambrose of Milan (+397):

O felix culpa quae talem et tantum meruit habere redemptorem… O happy fault that merited for us so great, so glorious a Redeemer.

St. Augustine of Hippo (+430) wrote: Melius enim iudicavit de malis benefacere, quam mala nulla esse permittere… For God judged it better to work good out from evils than not to permit any evils to exist” (ench, 8). This is picked up by St. Thomas Aquinas (+1274) who explained that God allows evils to happen in order to bring not just good, but a greater good therefrom (STh III, 1, 3, ad 3).

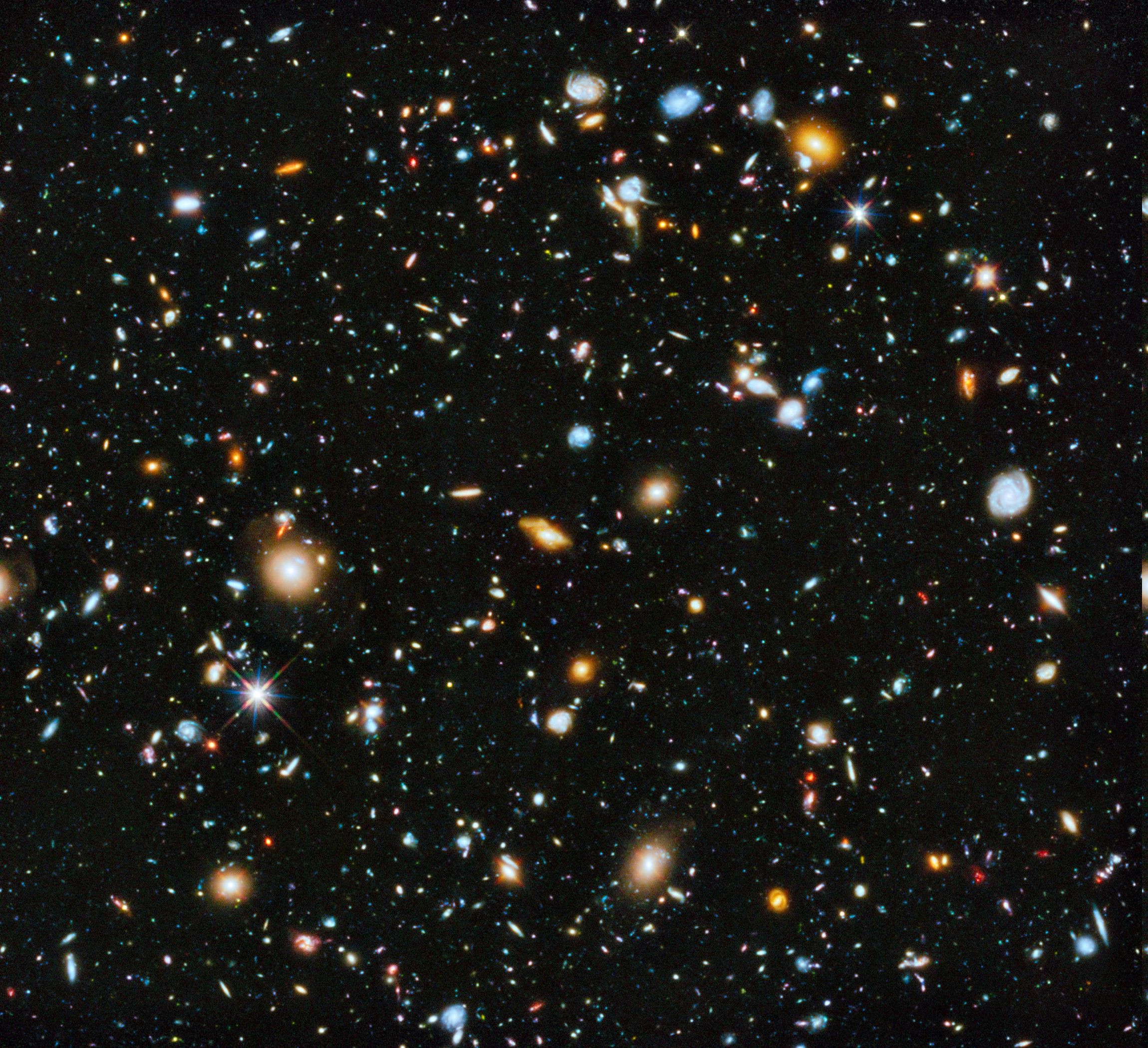

As an aside, about the ordering of creation, it has been proposed, conjectured, speculated, contemplated that everything that moves would have its angel to guide it. As science goes apace, we have moved from thinking that all things are composed of the four elements of earth, water, air and fire in different proportions. Eventually we figured out molecules and atoms and then what made up atoms and what makes up what makes up atoms. There are dazzling arrays of little creatures all groaning for the revelation of the sons of God, quarks and leptons and bosons and spinons. There are even up quarks and down quarks and antiquarks. When will our discovery into the infinitesimally tiny end? And if in the particles, then in the aggregates they form even unto galaxies and clusters of galaxies. How far will we eventually be able to see? How big is this cosmos and how small? And there are angels that guide everything that moves? That’s a lot of angels. A third fell. That’s a lot of enemies. As a slight continuation to the digression, those that fell still have, in a sense, the mission for which they were created and they still, in a twisted way try to fulfill it by distorting it, it’s purpose. As an exorcist explained to me, fallen angels want names, in that they lack them and they want them. There is an adage that “naming calls.” Don’t invoke “spirits of this or that.” You might get more than you bargained for.

In any event, this vision of creation is a starting point of hopeful longing as well as a prompt for responsible use of creation, our fellow groaner after freedom.

Finally, I will share something beautiful from Dom Prosper Guéranger from The Liturgical Year about this Sunday’s Epistle. You might keep in mind, as you read this, the image Paul uses in 1 Cor 13:12: “For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face.”

Men who recognize no other law than that of the flesh may be as deaf and as indifferent as they please to the teachings of positive revelation; but mere matter will go on ever condemning their materialism. Nature, which they pretend to acknowledge as their only authority, will continue to preach the supernatural with her thousand mouths, and will preach it in every nook of the earth ; and creation, disturbed though it be, and turned astray by the fall of Adam, will still keep proclaiming all the louder because it is in suffering—that the fallen king, whom it was intended to serve, has a destiny far beyond all finite things.

O ye mysterious sufferings of creatures, which the apostle here calls your groaning as, may we not name you, as one of the poets did, ‘the tears of things’ (Aeneid I.462)? Truly, you are like the soul of music of this land of trial; we have but to listen to your sweet plaintive sounds, and let you speak your eloquence, and you lead us to Him who is the source of all beauty and love. The pagan world heard your voice; but its philosophers would have it that you meant pantheism! The Holy Ghost had not yet begun His reign. He alone could explain to us the strange language of nature, and her vehement aspirations, all of which had been put into her by Himself. All is now made clear to us: the Spirit of the Lord hath filled the whole earth; the divine witness, who giveth us assurance that we are the sons of God,’ has carried His precious testimony to the farthest limits of creation; for all creation thrills with expectancy, impatient to see the coming of that glorious day which is to be the revelation of the glory that belongs to these sons of God. It is on their account that they too have had to suffer; together with them they shall be set free, and shall share in the brightness of their coronation day.

Stick that in your demonic Pachamama pantheism and smoke it.