As Pius Parsch wrote in The Church’s Year of Grace,

The next six weeks may well be the most important time of the year.

Why would this be?

Today we are raw recruits, at Easter we will be proven soldiers.

How do we get from here to there? By remaining in the unity of Christ.

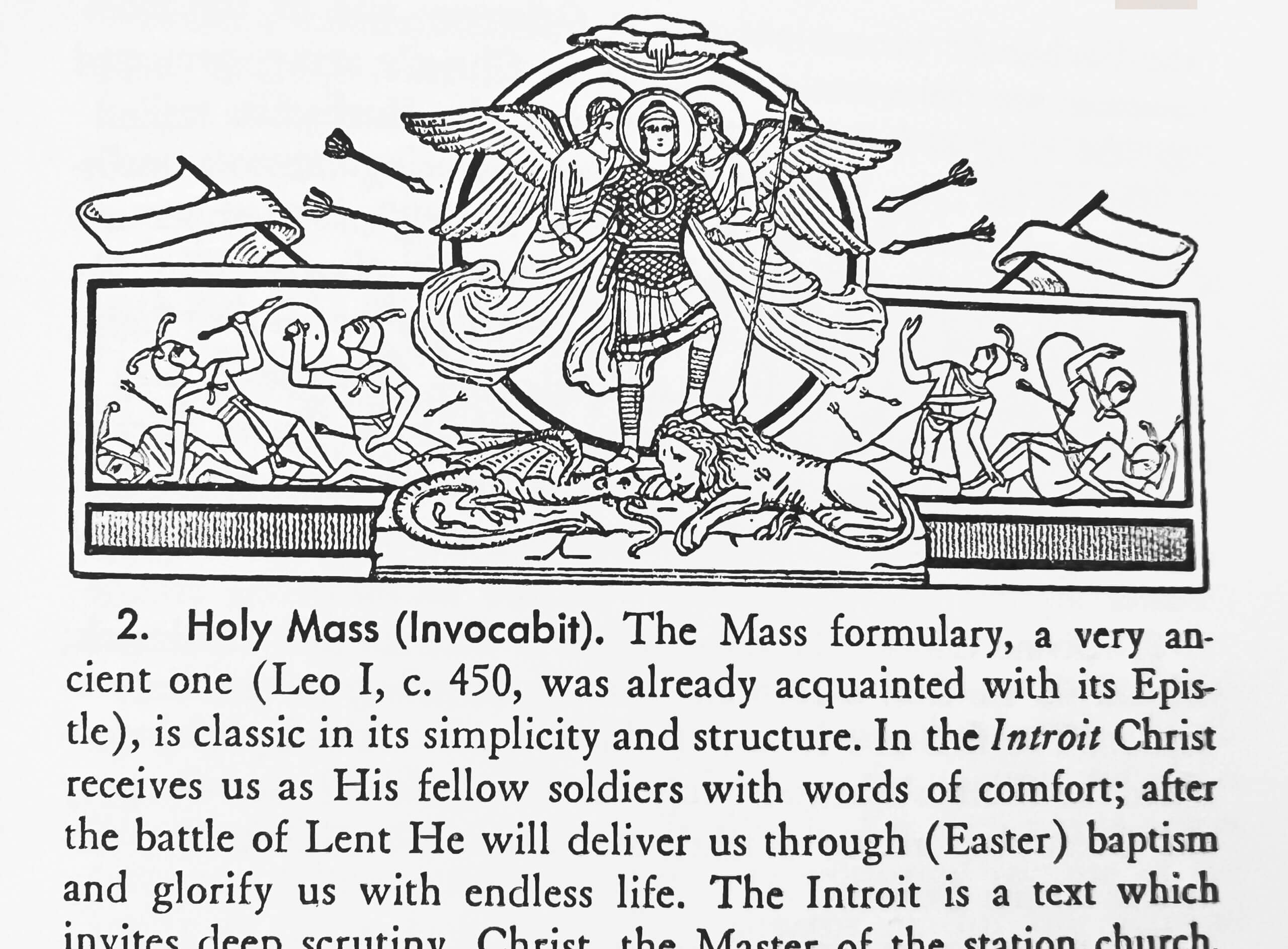

Parsch gives us a helpful image based on this Sunday’s Gospel.

In the Gospel reading for this 1st Sunday of Lent we hear the pericope about how the Enemy thrice tempted Christ after forty days in the wilderness. The temptations and their overturning by the Lord, the new Adam, recapitulate the elements of temptation of our First Parents in the Garden, the roots of all other sins which 1 John 2 summarized as lust of the flesh, lust the eyes and pride of life. The fruit in the Garden was good for food, a delight to the eyes and it would make them wise as if they were gods. They were tempted and fell in wanting to satisfy their appetites, take possession of what they saw, and fulfill self-pride in having done so.

Back to Parsch:

The gospel shows us Christ in a double role, as a penitent and as a warrior. First we follow him as the penitent par excellence into the desert of self-denial to fast with him for forty days. Our fast will be spiritually fruitful if we keep it in unity with Him, if it is an extension of His fasting. …The fast of Christ formed a part of His work of redemption; for us too the forty day season of penance contributes to His mission of constructing God’s kingdom on earth. The next six weeks may well be the most important time of the year.

Our Redeemer also goes before us as a warrior. We see the divine Hero victorious on three fronts. Two princes stand face to face, the Prince of this world, and the King of God’s kingdom. The Prince of this world deploys his whole army: the world and its splendors, hell, the ego with its insatiable desires. But Christ emerges as the winner.

Ancient Roman catechumens heard the aforementioned Gospel sung in their cathedral, St. John Lateran, also known as the Basilica of the Holy Savior.

Be mindful that in ancient times this Sunday was the beginning of Lent, so the very first words of the Eucharistic liturgy are our bridge into the sacred season, called by St. Leo the Great (+461) as a sacramentum. The Introit for this Mass is from Ps 90 (modern numbering 91) which is the very psalm Satan quotes to Christ. Ps 90/91 is heard again in the Gradual chant, and a long portion of it forms the Tract that replaces the now-buried Alleluia. The fact that the Tract is very long (nearly all of the psalm) is a remnant of how things were in the ancient church. Together those two chants form a bridge from the Epistle to the Gospel. Ps 90/91 is heard again in the Offertory – the bridge into the sacrificial part of the Mass – and in the Communion antiphon – the bridge to reception of the Eucharist by the people – when the manifestation of Christ as the Head of the Church meets the manifestation of Christ as the Body of the Church. Each of those stages have processions: to the ambo to sing the Gospel, to the altar with the vessels and offerings, to the place of distribution of Communion. Ps 90/91 weaves the Mass together.

Quoting Ps 91 – let’s call it 91 so it is easier for you to find in your modern Bible editions or online – the Devil tempted Jesus to succumb to the sin of pride by throwing Himself off the high place of the Temple precisely so that people see and would marvel at His rescue by angels: angels will “bear you up lest you dash your foot against a stone” (v. 12).

The whole of Psalm 91 is about the many types of danger we are in in God’s service, on the one hand, while at the same time it sings the assurance of God’s protection. Yes, scourges and diseases and arrow and serpents. But also, yes, God’s protection for the faithful in what really matters.

This year in these columns we are mainly concerned with the Epistle reading. Holy Church has made it challenging for us to do that because, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, she provided us in the formularies for these Sundays a magnificent woven tapestry in which every thread and figure they depict as intimately related.

So we turn with trembling respect to the Epistle Reading from 2 Cor 6:1-10, which again in her wisdom our Mother the Church has had us read every year at the beginning of Lent for some fifteen centuries. Must be a reason for that, no? In the reading that follows, Paul quotes Isaiah 49:8, which was about the imminent liberation of the people from the Babylonian Exile. The word Paul uses for “time” is kairos, which can denote a special moment, a turning point, rather than just time which is chronos, as in “tick tick tick tick.” A kairos is like the proverbial moment of choice or fork in the road which, as Robert Frost says, “made all the difference.”

Brethren: Working together with him, then, we entreat you not to accept the grace of God in vain. For he says,

“At the acceptable time I have listened to you,

and helped you on the day of salvation.” [Isaiah 49:8]Behold, now is the acceptable time [Greek kairòs euródextos – as in the moment when a promise is fulfilled]; behold, now is the day of salvation. We put no obstacle in any one’s way, so that no fault may be found with our ministry, but as servants of God we commend ourselves in every way: through great endurance, in afflictions, hardships, calamities, beatings, imprisonments, tumults, labors, watching, hunger; by purity, knowledge, forbearance, kindness, the Holy Spirit, genuine love, truthful speech, and the power of God; with the weapons of righteousness for the right hand and for the left; in honor and dishonor, in ill repute and good repute. We are treated as impostors, and yet are true; as unknown, and yet well known; as dying, and behold we live; as punished, and yet not killed; as sorrowful, yet always rejoicing; as poor, yet making many rich; as having nothing, and yet possessing everything.

Those hardships and their contrasts are signs of Paul’s authority, his right to correct and instruct them.

However, how does that list of hardships line up with the over-arching message of Ps 91 which is precisely about the assurance of God’s protection?

Paul had founded the Christian community in Corinth. After he left for Ephesus, many problems cropped up in the community that Paul had to deal with from a distance. Internal evidence in the two Pauline letters addressed to the Corinthians that we now have reveal that he wrote to them at least four times. The two we have were his second (1 Cor) and fourth (2 Cor) though scholars debate these things as scholars are wont to do. It seems that the third letter was real hard-ball, for Paul said: “I wrote you out of much affliction and anguish of heart and with many tears” (2 Cor 2:4). In any event, in 2 Corinthians 11, another chapter in which Paul lists his hardships and which we heard on Sexagesima Sunday, we learn that there were in among them as there are among us today in great numbers,

false apostles, deceitful workmen, disguising themselves as apostles of Christ. And no wonder, for even Satan disguises himself as an angel of light. So it is not strange if his servants also disguise themselves as servants of righteousness. Their end will correspond to their deeds.

Again and again the Church gave the aspirants for baptism, the catechumens, a clear picture of what Christian discipleship involves. And she repeated them year in and out so that, as these catechumens went from being new Christians to seasoned Christians and perhaps also clergy, they would be well-known and available for constant reflection and examination of conscience. On the negative side, there may come poverty, persecution and attacks on reputation with lies and calumny. Mortification of the flesh will be required. On the positive side will be not material benefit, but rather gladness of souls, the receptions of gifts of grace from God, the opportunity to edify others and to be of help to the needy. The negative and the positive will both be at work in us, as will the lower aspects of who we are with the higher. Which will prevail will depend on our commitment to Christ in the sacramentum, the mystery, of Lent. As Bl. Ildefonso Schuster put it:

The people of God could not begin the paschal fast under happier auspices. Christ precedes them into the desert of expiation. The Apostle follows, and in one of the noblest of his epistles shows them how fastings, persecutions, and bodily sufferings are outweighed by the gifts of the Holy Ghost, longanimity, meekness, joy and suffering for love of God, happiness in serving one’s fellow-men, in such ways sharing with Christ the sublime ministry of the redemption of mankind.

I return to Pius Parsch again for a moment, and his remarks on the importance of the Lenten discipline for our spiritual lives:

Now the battlefield is not far from any one of us; it is in my soul where the higher and lower man are ranged against each other. Christ in us must be victorious. From this conviction flow strength and solace; we are not alone in the battle, head and members fight together, head and members win together. Thus the Gospel is our first lesson in the training school of Christ; today we are raw recruits, at Easter we will be proven soldiers.

We can do this, with each other in support and with Christ in us to win the victory.

Since the idea of conflict runs through the Mass, in the Gospel face off, in the Pauline contrasts of factions on the wrong and right sides, his own experiences, and since I’m feeling particularly quotey today, here is an observation from Dom Prosper Guéranger in his monumental The Liturgical Year. He is writing here of the Epistle reading we have for this Sunday:

These words of the apostle give us a very different idea of the Christian life from that which our own tepidity suggests. We dare not say that he is wrong and we are right; but we put a strange interpretation, upon his words, and we tell both ourselves and those around us that the advice he here gives is not to be taken literally nowadays, and that it was written for those special difficulties of the first age of the Church, when the faithful stood in need of unusual detachment and almost heroism, because they were always in danger of persecution and death.

How many times do we hear today from leftists and modernists, German theologians and Jesuits activists, that “that was maybe true back then, but this is now; that teaching was culturally conditioned and doesn’t apply to us anymore!”? Let’s go on with Guéranger:

The interpretation is full of that discretion which meets with the applause of our cowardice, and it easily persuades us to be at rest, just as though we had no dangers to fear, and no battle to fight; whereas, we have both: for there is the devil, the world, flesh and blood. The Church never forgets it ; and hence, at the opening of this great season, she sends us into the desert, that there we may learn from our Jesus how we are to fight. Let us go; let us learn, from the temptations of our divine Master, that the life of man upon earth is a warfare,’ and that, unless our fighting be truceless and brave, our life, which we would fain pass in peace, will witness our defeat. That such a misfortune may not befall us, the Church cries out to us, in the words of St. Paul: Behold ! now is the acceptable time. Behold! now is the day of salvation.

We are at a promised fork in the liturgical year’s road, which means for us Catholics – because we are our rites – a turning point upon which the rest of our lives – taken serious, may hinge.

I remind the honorable reader, warrior penitent that you are, of Parsch’s great insight, cited above: “The fast of Christ formed a part of His work of redemption.”

If for Him, then for us. It is part of our journey, nay rather, battle, for salvation.