In 589 Deacon Aigulf trekked home to Tours with relics he had collected in Rome. St. Gregory of Tours relates in his Historia Francorum that Aigulf saw with his own eyes the disasters that struck Rome that year. The Tiber rose to such a flood that buildings were washed away, ancient temples destroyed, and the Church’s food storehouses were lost. There was an invasion of snakes, some the size of logs, which were washed to the sea. In November a plague they called “inguinaria” (of the groin) struck. It killed Pope Pelagius I and a great many others. It was in these cataclysmic days that the people chose a certain Roman Deacon Gregory to be their new Bishop.

Deacon Gregory was from a Senatorial family. He had established many monasteries in and around Rome. He sold his house and all his belongings and gave to the poor, fasting so much that he could barely stand. Gregory begged not to be elected to high office, but he was overridden. Even the Emperor implored him to take the role. At that time, Gregory bade the people to sing psalms and beg God’s mercy for three days. As Aigulf’s eyewitness account runs:

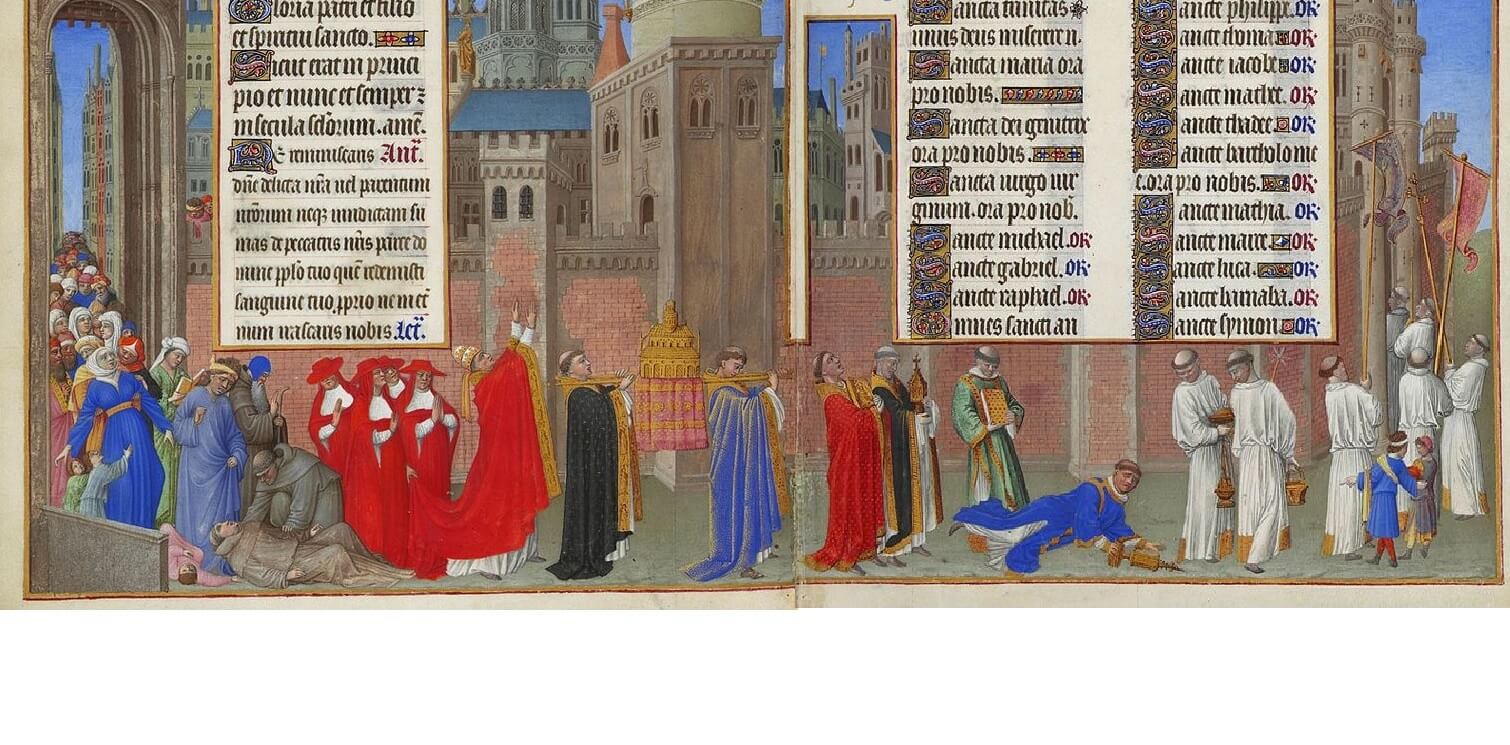

Every three hours choirs of singers came to the church crying through the streets of the city “Kyrie eleison.” Our deacon who was there said that in the space of one hour while the people uttered cries of supplication to the Lord eighty fell to the ground and died. But the bishop did not cease to urge the people not to cease from prayer. It was from Gregory while he was still deacon that our deacon received the relics of the saints as we have said.

When Gregory was making ready to flee to a hiding place he was seized and brought by force to the church of the blessed apostle Peter and there he was consecrated to the duties of bishop and made pope of the city. Our deacon did not leave until Gregory returned from the port to become bishop, and he saw his ordination with his own eyes. (Historia Francorum X.1)

One year after those dire events in Rome, new Pope and future St. Gregory “the Great” (+604) was the only major figure standing who could deal with ongoing plagues, a series of destructive earthquakes that brought down cities, and an invasion of not-so-legal and not-so-peaceful “immigrants” from the north. At end of November of 590, the beginning of Advent, Gregory preached a sermon about the very Gospel passage we still read today in the Vetus Ordo for the First Sunday of Advent.

Yes, the same Gospel passage from Luke 21:25-33 – about the signs of the time and Second Coming of Christ at the end – has been read in Roman Catholic churches since before the time of St. Gregory the Great. Year in and year out. In times dire and in times benign.

Gregory began his Advent sermon:

As our adorable Savior will expect at His coming to find us ready, He warns us of the terrors that will accompany the latter days in order to wean us from the love of this world; and He foretells the misery which will be the prelude to this inevitable time, so that, if we neglect in the quietness of this life to fear a God of compassion, the fearful spectacle of the approaching last judgment may impress us with a wholesome dread.

A short time before He had said: Nation shall rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom. And there shall be great earthquakes in divers places, and pestilences and famines (Luke 21:10, 11).

Now He added: And there shall be signs in the sun and in the moon and in the stars, and upon the earth distress of nations.

Of all these events we have seen many already fulfilled, and with fear and trembling we look for the near fulfilment of the rest.

As for the nations which are to rise up, one against the other, and the persecutions which are to be endured on earth, what we learn from the history of our own times, and what we have seen with our own eyes, makes a far deeper impression than what we read even in Holy Scripture. With regard to the earthquakes converting numberless cities into lamentable heaps of ruins, the accounts of them are not unknown to you, and reports of the like events reach us still from various parts of the world. Epidemics also continue to cause us the greatest sorrow and anxiety; and though we have not seen the signs in the sun and in the moon and in the stars, mentioned in Holy Scripture, we know, at least, that fiery weapons have appeared shining in the sky, and even blood, the foreboding of that blood which was to be shed in Italy by the invading barbarian hordes. As to the terrible roaring of the sea and of the waves, we have not yet heard it.

However, we do not doubt that this also will happen; for, the greater part of the prophecies of our Lord being fulfilled, this one will also see its fulfilment, the past being a guarantee for the future.

Thus St. Gregory the Great preached to his flock in the hard times they endured. He underscored that they were to prepare well for the Second Coming of the Lord especially by detaching from the things of this world.

With Advent we begin a new liturgical year. Because many centuries ago Advent was longer by two weeks, the themes of the End Times stressed at the end of the previous year are carried on into the new. Advent is as much about preparing for the Parousia (Greek for Latin adventus), the Second Coming of Christ, as it is a penitential season readying us to celebrate His First Coming into the light of the world at Christmas.

For centuries, together with the description Christ gives of His return and the signs that will go before it, Holy Mother Church has also given us a reading from Paul’s Letter to the Romans about how to prepare for our meeting with the Lord, at death or when He comes in glory.

Paul tells the Romans in 13:11-14 to “wake up!” in terms that more and more ironically – or is it prophetically – contradict “woke”, the contemporary distortion of “wake”. For Paul “the day”, (meaning the Parousia) is “coming soon” (Greek eggizo). In several of his letters Paul works with imagery of putting off (apotithēmi) what is old and “of the darkness” and putting on (endyō) the new, what is “of the light” and he expresses it in terms of armor. Writing to the Romans, Paul contrasts being in the light (in the Christian character) with “works of darkness” (in pagan wokeness).

What are those works which we must eschew, or not be saved? The Douay-Reims translation renders them as “revelry and drunkenness, not in debauchery and wantonness, not in strife and jealousy”. I like the old KJV language:

- rioting (KJV) – komos – late night drinking parties that could spill out into the street (Galatians 5:21 and 1 Peter 4:3

- chambering (KJV) – koite – things that are done in a bed, such as adultery

- wantonness (KJV) – aselgeia – licentiousness, filthiness, perversions

- strife (KJV) – eris – contention, quarreling

- envying (KJV) – zelos – positive sense “zeal” but in the negative, “jealousy” or “malice”

These are the works of darkness. In Galatians 5:19, they are “works of the flesh”, that is: “fornication, impurity, licentiousness, idolatry, sorcery, enmity, strife, jealousy, anger, selfishness, dissension, party spirit, envy, drunkenness, carousing, and the like.”

Paul says: “those who do such things shall not inherit the kingdom of God” (v. 21).

Let’s be blunt: Do these things, knowing they are wrong (and people do), keep doing them unrepentantly, and you are going to go to Hell.

Continuing with the undressing/dressing imagery, in Colossians 5:9 Paul says to “put on Christ”.

Armor is not neutral. It is military. It is for defense and it is for offense. Our war is against our fallen nature and against the fallen angels in a fallen world. In Ephesians 6:10-18, Paul tells us to “put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil.” Inspired by the Prophet Isaiah, Paul breaks down the six pieces of armor in the Roman Legionary style and their symbolism:

Stand therefore, having girded your loins with truth (Is 11:5), and having put on the breastplate of righteousness (Is 59:17), and having shod your feet with the equipment of the gospel of peace (Is 52:7); besides all these, taking the shield of faith (Is 21:5), with which you can quench all the flaming darts of the evil one. And take the helmet of salvation (Is 59:17), and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God (Is 49:2).

Could we add a seventh? Paul concludes in v.18:

Pray at all times in the Spirit, with all prayer and supplication. To that end keep alert with all perseverance, making supplication for all the saints.

What greater weapon of devotional prayer in our spiritual armory do we have than the Holy Rosary? In 1883 Pope Leo XIII wrote in Salutaris ille spiritus precum:

“The Rosary was instituted principally to implore the protection of the Mother of God against the enemies of the Catholic Church.”

We might look at the Rosary as the cloak protecting us from the currents of the day, the winds of fad and fashion, that help us to remain watchful in our vigil rather than woke in erring slumber.

The Pauline imagery of putting off the works of darkness, the “old man” (Adam) and putting on light and the armor of God and the “new man” (Christ) runs deeply in our devotional and liturgical veins, or at least it does where the Vetus Ordo thrives. The imagery informs even the gestures of preparing for Holy Mass. Just as the priest has individual prayers for the vestments for Mass (his amice is a helmet to protect him from diabolical attacks during Mass like thoughts, temptations, evil prompts and images), so too the servers have a prayer quoting Ephesians 4:24 for putting on the surplice, the shorter white garment:

Índue me, Dómine, novum hóminem, qui secúndum Deum creátus est in iustítia et sanctitáte veritátis. Amen

Invest me, O Lord, as a new man, who was created by God in justice and the holiness of truth. Amen.

Douay and KJV have “new man”, while the RSV as “new nature”. The Greek says, “kainòv ánthropon” and the Vulgate, of course, “novum hominem”.

The alb and the surplice recall our white baptismal garments put on after we have shed the “old man” (fallen Adam) and have put on Christ (a new character in sanctifying grace, salvation).

For any bishops out there, think of the riches you have lost in not saying the magnificent vesting prayers for your celebration of Mass. When taking off the cappa magna, the wondrously long cape borne up by a server like a train, and the same for a cope, the bishop says, referencing Ephesians 4:24:

Exue me, Domine, veterem hominem cum moribus et actibus suis: et indue me novum hominem, qui secundum Deum creatus est in justitia, et sanctitate veritatis.

Take off of me, O Lord, the old man with his manners and deeds: and put on me the new man, who according to God is created in justice, and the holiness of truth.

The last part is like the altar boy’s surplice prayer.

Many bishops and priests were altar boys to start with. At least that’s how it once was. These prayers sink into the heart and marrow of a young man. I remember being instructed in Rome in the Benedictines’ cloister of the Basilica of St. Cecilia – on whose feast day I write this – about how to pray vesting prayers, beginning with washing my hands before even touching the perfect, crisp white linen surplice I was to put on to serve the rector’s early morning Mass for the nuns. As Monsignor said them, I repeated them and learned by rote the prayers for putting on my cassock, washing my hands, donning my surplice.

Perhaps over the years many clerics thought all of this was too nitpicky, repetitive, meaningless and so they sloughed off their “habits” and, with them, lost something precious in their identity. Armor gets heavy, too. It can chafe, burden. Taking it off lays you open to injury. So does the laying aside of virtue, which is a habit that makes doing that which is right easier when the hard moments flood in upon you, when the trials and plagues and life’s earthquakes arrive. Put aside traditions, our beautiful patrimony, and you put aside something of your identity.

The Latin phrase goes, repetita iuvant… repeated things help. Year in and year out we have our liturgical calendar and the repeated readings that convey mysteries that transform and instruction that saves. These mysteries and instructions don’t change, but we do as the years pass. Each year they touch us in ways both old, so that they sink in, and new, so that they lure us forward into their depths. The daily prayers and devotions we have, of rising and slumbering, eating and thanking, Rosary and Angelus and vesting for Mass, and all the jewels of meditations so lovingly crafted and polished and handed on inform us with an especially Catholic “thing”, a Christian Romanitas, each with our different cultural tones and hues.

As this Advent begins, consider how you can use more keenly and fruitfully the gift of this new liturgical year of grace.