The Lesson or Epistle for Mass on the 17th Sunday of Ordinary Time in the Vetus Ordo is from Ephesians 4:1-6.

[Brethren:] I therefore, a prisoner for the Lord, beg you to lead a life worthy of the calling to which you have been called, with all lowliness and meekness, with patience, forbearing one another in love, eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace. There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all, who is above all and through all and in all.

This Sunday in the ancient Roman Church came at the time of the fast of the “seventh month,” which is during “Seven-tember.” It is still called “7 month” though it was bumped down by the introduction of the months named after Julius and Augustus Caesar. The seasonal fast could have been established in the ancient Church as a counter to the pagan harvest festivals which could lead to excesses. During this last week we observed the autumn Ember Days.

The Introit of the Mass comes from Ps 118, “Beati immaculati in via” which might refer to the penitential processions made in the streets of Rome at this time.

Of our Sunday Lesson Bl. Ildefonso Schuster remarks:

The passage from the Epistle to the Ephesians (iv, 1-6) vigorously impresses upon us the idea of the unity of the Christian family, a unity founded on the identity of the Spirit which inspires all the members of the mystical body of Jesus Christ. God is one, the faith is one ; there is one baptism and one bishop. With these words in olden days the Romans, making a tumult in the Circus, answered the heretical Emperor Constantius, when he proposed to allow the Antipope Felix II, whom he himself had appointed, to reside in peace beside Liberius, the staunch defender of the Nicene faith.

What is Schuster talking about. Tumult? Antipope? Two Popes?

Space constricts me to a thumbnail sketch of the historical context of that remark. Constantine’s son Constantius was an Arian heretic. He persecuted St Athanasius and threatened bishops into turning from him. Some saintly bishops refused. They were “cancelled” by Constantius and sent into exile, including Sts. Eusebius of Vercelli, Lucifer of Cagliari, and Hilary of Poitiers. Rome’s bishop Liberius also did not play ball and was exiled in 354. According to the Collectio Avellana (CSEL 35: 1-4), Rome’s clergy then swore they would have no other than Liberius who was still alive. But, fickle, they supported a deacon named Felix, and made him Rome’s bishop (aka Antipope Felix II). The people refused to take part in the ceremonies, including the customary procession of the new Pontiff. A couple years later when Constantius came to Rome the whole people clamored for Liberius to come back. Liberius returned and Felix was thrown out of Rome. However, Felix returned and, with some clergy, took over the Basilica Julia in Trastevere, now Santa Maria in Trastevere. The Romans tossed him out again. Liberius remained some years, after pardoning the rebellious clergy. Meanwhile, Liberius passed away (+366) and Felix too died (+365). When Liberius died, a deacon Ursinus was made bishop. However, at San Lorenzo in Lucina other clergy elected a deacon Damasus (later Pope Damasus I +384) who had been in exile with Liberius. Damasus was supported by the former supporters of Felix while Ursinus was backed by deacons. This is where the real darkness happens. Accounts not favorable to Damasus said that Damasus organized and armed mobs and brought in gladiators, charioteers and gravediggers. According to the Collectio, they slaughtered people for three days. He seized the Lateran, was consecrated, and used violence to quell opposition. He eventually ransacked the Lateran and set it on fire. In short, Ursinus lost and Damasus won. The ancient historian Rufinus and St. Jerome backed Damasus. St. Ambrose says (ep 4) that Urbinus wound up in Milan with the Arians. In 378 a synod condemned Ursinus and declared Damasus as the legitimate Bishop of Rome. The tale is more complicated, but that’s the quick version.

What do we draw from this, in light of the Epistle reading from St. Paul to the Ephesians?

This Mass reading is mainly about the unity of the Church. The episodes related above manifest quite the opposite. Eventually, things sorted out, for the Church cannot falter fully into dissolution. Similarly, because of Christ’s promises we know that, because the Petrine Ministry is part and parcel of the true Church, Successors of Peter can be wicked or incompetent or disastrous, but they can never be total disasters, so much so that the Church cannot continue.

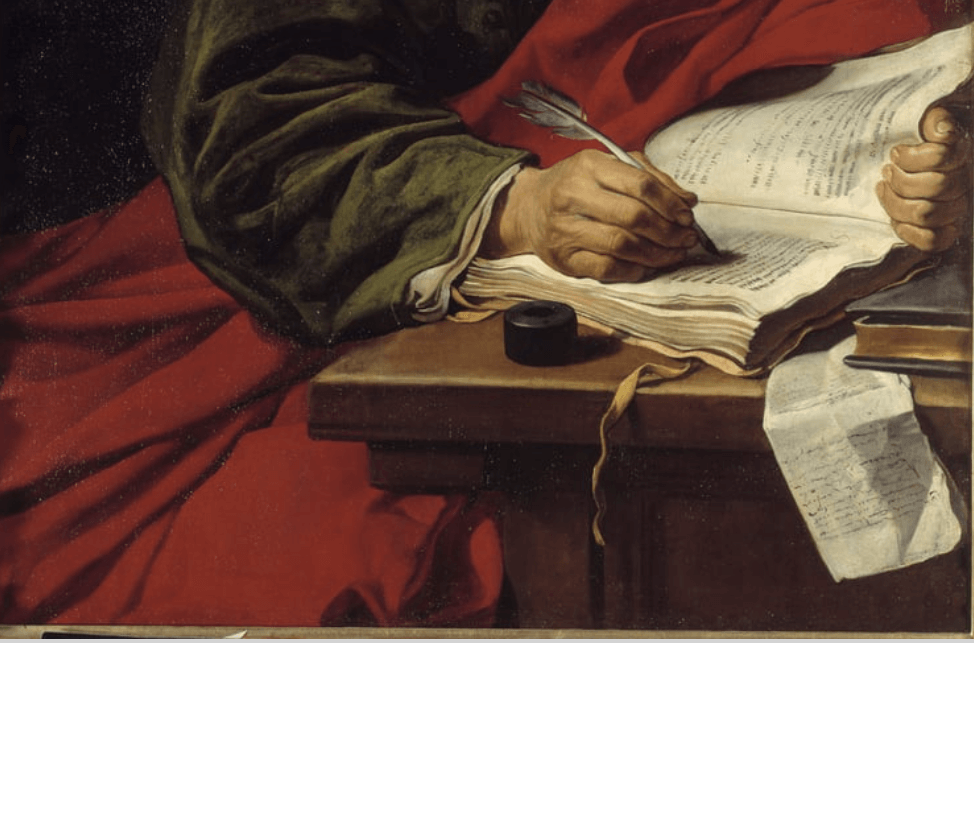

Paul wrote this Letter to the Ephesians when he was imprisoned, probably in Rome. In the Prison Epistles (e.g., Colossians, Philippians, Philemon) he brings up his own suffering when addressing the issue of the unity of the community to which he is writing. Paul suffers, he says, for the sake of the Gospel from outside persecution by authorities. But he also suffers because of another kind of persecution, divisions within the Church.

Divisions within the Church are more painful than persecutions from without. They have the feel of fratricide, of Judas-like betrayal no matter who is against whom. Those who are members of the Mystical Body of Christ through Baptism are the adoptive and real children of God, brethren on an even higher plane than blood.

That said, I remark on the hot bloodedness of the ancient Church. St. Augustine complained to St. Jerome about his new-fangled translation of Scriptures. People were confused and upset when they heard new versions of their familiar texts. They even rioted. During the Arian controversy, which is part of the debacle in Rome in the 4th century, above, people rioted over one letter, the iota in or absent from homoousios (same substance) or homoiousios (like substance). They took the Faith seriously. Emperors had to weigh with military force into theological disputes because they disturbed the civil peace and unity of the Empire. The problem with the Donatists in N. Africa got so bad that the exasperated St. Augustine asked for such force to compel the heretics into unity (ep 73).

Unity is important. So much so that Paul begs the Ephesians to embrace meekness, patience and forbearance in brotherly love (Greek agape). So important is unity that we have make sacrifices of our ego. Because there is one God and Father, one Lord, one faith, and one baptism, one body and Spirit, in effect one Church, we have one hope that results from the “call” (klésis). Greek klésis derives from the verb kaléo, “to call, to invite, to give a name to.” We are all called. The Latin we read at Mass says, “sicut vocáti estis in una spe vocatiónis vestrae… just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call.” Surely you make the connection with the English word “vocation.” It can happen that people will associate “vocation” only with the calling by God to be a professed religious or to be a priest, and that surely is a strong and prevailing meaning of vocation. Paul, however, is using an even more fundamental meaning of vocation, calling, klésis. It is one that flows from all those “ones” above, particularly through what we become in the waters of baptism: children of the Father, one in faith, hope and love, disciples of one Lord after whose beautiful title Anointed One we are “called,” Christians. We are called into the Church, into the ecclesia … or rather with the Greekier spelling ekklesía. Do you see the root of the very term for the Church is from “call”? The early Church borrowed this ancient Greek term for “called-out assembly” of the citizens of city-states, such as Athens.

Our calling in the Church flows from our baptism and unity with Christ. The bond of unity is so constitutive and powerful that it must – we must by our fundamental calling overcome the tensions that diversity of expression, insight, culture will naturally bring out amongst those who are wounded with the effects of Original Sin and who are targeted by the Enemy of the Soul, the primordial sower of division.

Lastly, I recently read a piece in the journal Communio by His Eminence Robert Card. Sarah called “The Inexhaustible Reality: Joseph Ratzinger and the Sacred Liturgy” (vol. 49, Winter 2022). In the first part, Sarah reviews how Joseph Ratzinger’s thought about the Conciliar Reform of the Liturgy shifted over time from being quite optimistic to being much less so once its fruits were manifesting. Sarah quotes 39-year old Ratzinger from 1966 who uses a verse from our Epistle (cf. also Col 3:12-15, also about unity) about “bearing with one another, forbearing” (from Greek anechō):

[T]he liturgical reform calls for a very generous measure of tolerance within the Church, which in the given situation is only another way of saying that it calls for a great measure of Christian charity. And the fact that this charity is often so little to be found is perhaps the real crisis for liturgical renewal in our midst. The “bearing with one another” of which Saint Paul speaks, the diffusion of charity of which we read in Saint Augustine. It is these alone that can create the setting within which the revival of Christian worship can grow in maturity and achieve its true flowering. For the real divine worship of Christianity consists in charity.

Later in his essay, Card. Sarah observes:

It is profoundly to be regretted that the motu proprio Traditionis custodes ( July 16, 2021) and the related Responsa ad dubia (December 4, 2021), perceived as acts of liturgical aggression by many, seem to have damaged this peace and may even pose a threat to the Church’s unity. If there is a revival of the postconciliar “liturgy wars,” or if people simply go elsewhere to find the older liturgy, these measures will have backfired badly. It is too early to make a thorough assessment of the motivations behind them, or of their ultimate impact, but it is nevertheless difficult to conclude that Pope Benedict XVI was wrong in asserting that the older liturgical forms “cannot be all of a sudden entirely forbidden or even considered harmful,” particularly when their unfettered celebration has manifestly brought forth good fruits.

Let us embrace the old but true chestnut, often but wrongly attributed to St. Augustine:

In necessariis unitas, in dubiis libertas, in omnibus caritas.

Let us have unity in necessary things, liberty in doubtful things, and in all things charity.