The onset of Hansen’s Disease comes with patches of skin that change color and become numb. If left untreated, it can result in paralysis, the reabsorption into the body of the extremities, ulcerations, blindness, disfiguration. It is not highly contagious, but it can spread through contact or breathing in airborne droplets from coughs. Most people have a natural immunity and only about 5% of people are at risk to get it. People didn’t know that in the 1st century AD. It is treated, and can be cured, with multiple antibiotics over time. But people in Jesus’ day didn’t have those things. They didn’t know it came from a microscopic nerve-attacking organism Mycobacterium leprae. All they knew was that the disfiguring and necrotic progress of Leprosy was terrifying. It was associated with sin and ritual uncleanness.

In the Old Testament, Hebrew tsara’ath, usually translated as “leprosy,” can be a variety of things, skin diseases certainly, but also even mildew on the wall, mold on something.

In Leviticus 13 we have the Law given by God to Moses about how the priests should diagnose leprosy (or whatever other skin disorder it might be) and in Lev 14 how to reconcile and ritually cleanse someone who recovered from a skin disorder (which also suggests that “leprosy” meant more than Hansen’s Disease).

What if, in the time of Jesus, you got leprosy?

The Law in Leviticus 13:45-46 required that people with this defilement must wear torn clothing, live outside the camp, leave their hair unkept, cover the lower part of their face and cry out “Unclean! Unclean.” So, there is an outward display corresponding to the disorder.

This treatment hasn’t yet made its way into documents suppressing the Vetus Ordo. After all, it is written right there in a black on white that the repressive actions against the faithful who desire Traditional are not intended to marginalize anyone. Give them just a little more time.

Lepers were decidedly unpopular in ancient times. They were forced to live apart, and usually in groups or colonies. That doesn’t mean that they were absolutely ostracized. Remember that “leprosy” meant more than just Hansen’s Disease. People recover from contact dermatitis or shingles. Their loved ones took care of them. In the tiny modern town of Burquin in the area between ancient Samaria and Galilee there is an early church dedicated to St. George, nicknamed the Church of the Ten Lepers. Nearby is an underground well and a kind of cave where it is thought lepers would sojourn. There were found holes in the ceiling of the enclosure through which it is thought food was dropped to the poor souls within.

For this 13th Sunday after Pentecost we have the encounter between Our Lord and Ten Lepers from Luke 17. Not only are these ritually outcast, one of them is a Samaritan. A leprous Samaritan. You couldn’t get much more pathetic than that in 1st century Jewish eyes. Sort of like, today, a Catholic who wants not only the Vetus Ordo, but the pre-1955 rites.

Last week, from Luke 10, the Good Samaritan appeared in a parable. This week, from Luke 17, a flesh and blood Samaritan shows up. You will recall that the Samaritans and the Jews were not on friendly terms, to say the least. They were quite hostile. The Samaritans were the ethnically intermingled remnants of the Ten Tribes scattered by the Assyrians and then blended with imported Gentiles. They had their own worship on Mount Gerazim and recognized only the first five Books of Moses, the Torah. They were, in the eyes of the Jews of Judea in the south, religiously and ethnically unclean.

Our geographical context for the Gospel, comes from the Gospel itself, as does where Jesus is going.

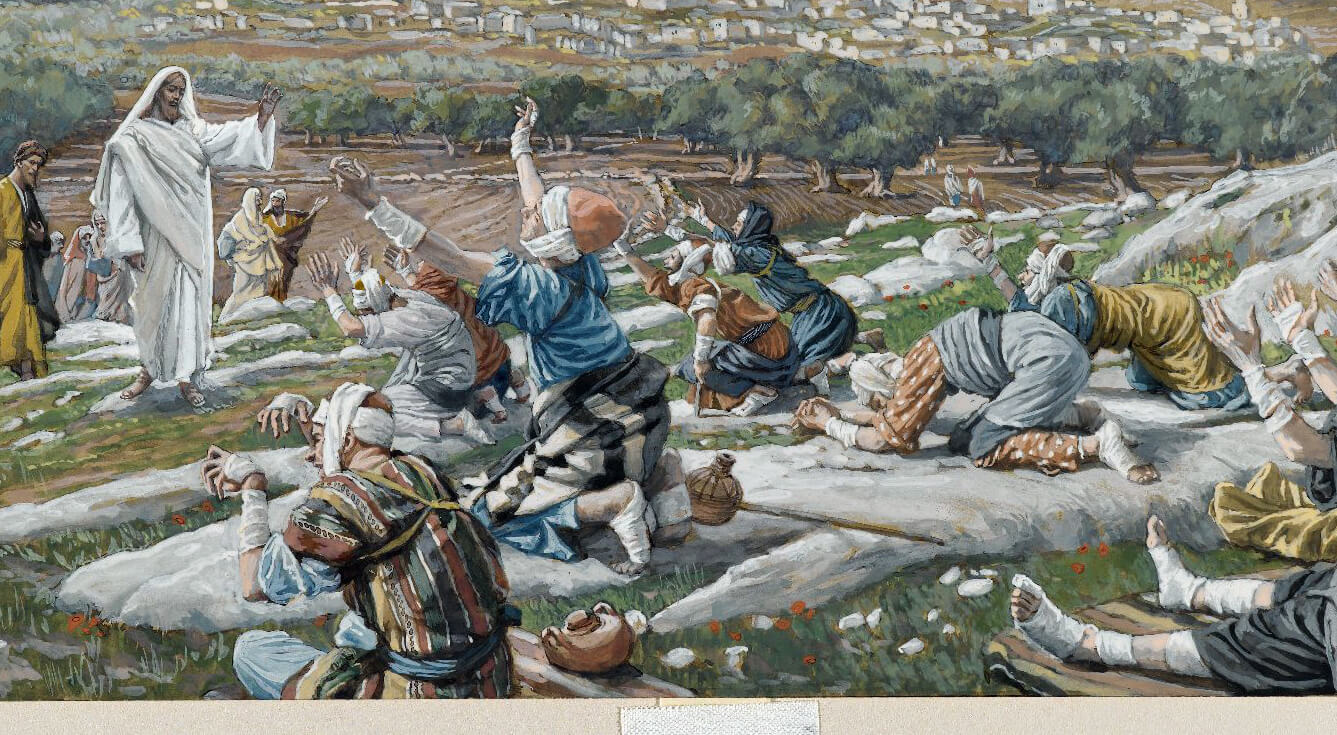

At that time, on the way to Jerusalem Jesus was passing along between Samaria and Galilee. And as he entered a village, he was met by ten lepers, who stood at a distance and lifted up their voices and said, ‘Jesus, Master, have mercy on us.’ When he saw them he said to them, ‘Go and show yourselves to the priests.’ And as they went they were cleansed. Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice; and he fell on his face at Jesus’ feet, giving him thanks. Now he was a Samaritan. Then said Jesus, ‘Were not ten cleansed? Where are the nine? Was no one found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?’ And he said to him, ‘Rise and go your way; your faith has made you well.’

In the Gospel, you see the elements from Leviticus. Remember that the Lord came to fulfill the Law. After He healed the lepers, He sent them to the priests for examination according to the Law.

Only one of the lepers returns. The lowly Samaritan, this “foreigner,” as the Lord calls him, recognized what superseded the Law in Leviticus and returned to Life Himself. “Foreigner,” Greek allogenes. This word appears once in the New Testament. In making His pronouncement over the allogenes we see Christ’s mission as not to the Jews merely, but to all peoples. A Samaritan is like “all peoples” because of their history.

By the way, there was discovered a complete stone inscription, the “Soreg Inscription,” in Greek and Latin from the Second Temple in Jerusalem, which would have been on the balustrade outside the Sanctuary.

Let no foreigner [ΑΛΛΟΓΕΝΗΕΙΣ] enter within the parapet and the partition which surrounds the Temple precincts. Anyone caught [violating] will be held accountable for his ensuing death.

This was a warning to pagans, non-Jews, not to pass into the sanctuary on pain of death. The text is almost word for word what the 1st c. Jewish historian Josephus described. It is usually a good idea to trust our ancient sources.

As we consider this physical remnant from the Second Temple, which Jesus would have gazed at, knowing Himself and His mission, remember how furious He was on that first Palm Sunday to find that the money changes and sacrifice vendors had taken over the Temple’s Courtyard of the Gentiles, where those who were denied entrance to the Sanctuary could still pray to the One True God. One can hardly imagine that St. Luke the Evangelist didn’t have this inscription, and perhaps this miracle which only he recounts, in mind. The arrival of Gentiles who wanted to speak to Jesus was a sign that His Passion was about to begin (John 12:20-22).

One could go into the theological depths of this pericope from Luke 17. For example, a symbolic level, we might look at the Ten Lepers as representing the sins against the Ten Commandments.

However, there is something in the recent news with which we might engage.

The Samaritan, former leper, returned to Jesus. He “fell on his face at Jesus’ feet giving thanks (‘euchariston’ v. 16).” The presence of a form of the word that gives us Eucharist should make us linger.

The ten lepers engaged with Jesus from afar from the desire to be cleansed. It was useful for them to have an encounter with the famous healer. When Christ told them to go the priests, they knew – and none better – what the procedure was and they went without looking back. Except for the “foreigner,” a Samaritan.

At first, the Samaritan also went to Jesus, though far off, for a useful healing. After his healing, he went back to Jesus, all the way up to Jesus, not because it was useful to do so, it was right to do so. He went simply to “give Him thanks,” and to do so in the posture one takes before divinity. Face down to the dust whence we come.

Another point that we pick up is Christ’s words to the Samaritan: “Rise and go your way” (v. 19). Breaking it into its elements, this account starts to take on a quasi-liturgical quality to it.

In the grouping of the Ten Lepers, there was an assembly for that moment when Christ was to draw near. There is a cry for “mercy.” Christ cites Scripture. He works a divine wonder. The Samaritan draws close, to His very feet, lowly in thanksgiving. Christ sends him forth. Sound familiar?

I have in mind the recent interview of Bishop Robert Barron with actor Shia LaBeouf. This young man, who wound up in serious personal quicksand, estranged from parents, marginalized by agents and directors, a sort of leper in his field, found his way to the Catholic Faith. At first, he was interested in a prospective acting job that could get him working again, a movie about St. “Padre” Pio. It was useful for him to draw close to Catholic things. Eventually he finds self-described healing in Mass in the Vetus Ordo, which was the only form of Mass St. Pio ever celebrated. In his encounters with Mass and men of faith, and the Catholic “thing,” he is Catholic. He is present to it in its beauty, in its healing touch.

Holy Mass, particularly as celebrated – these days in particular – with the Vetus Ordo, more clearly manifests the fact it is not focused on man. It is focused on God. Certainly, we participate at Holy Mass because we desire that transforming touch in our encounter with divine mystery. But it is not the usefulness of Mass as being transformational that is primary. It is the religious rightness of being there, in awe-filled gratitude, for the sake of God. Of course, the one does not exclude the other, such is the magnificent love of our God. Paradoxically, the more we allow Mass to be less about ourselves, then the more it affects us. Our “active participation” in Holy Mass is rooted in our active receptivity, our outpouring of self that opens for the inpouring of what God wants to give.

Finally, you will likely admit that learning you have Hansen’s Disease would be disagreeable. How much more disagreeable should it be to find that you are in the state of mortal sin? In the first case, the cure might take a couple of years. In the second, it takes but a few minutes, if only you seek that cure. You should “Go and show yourselves to the priests.”

Go to confession.