Let’s have a peek at the Gospel for this 12th Sunday after Pentecost in the Vetus Ordo.

Context. In Luke 10, the Lord has sent out the 72, two by two, with instruction about how to travel and behave. He pronounces a terrible destiny, worse than Sodom, for Chorazin and Bethsaida and Capernaum which had rejected the Lord. The 72 return with their stories about casting out demons. Our Lord, revealing something of His divinity, said, “I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven.” Then Our Lord makes a short speech which seems to have provoked a lawyer. Christ, “in that same hour,” “rejoiced in the Holy Spirit” and said:

All things have been delivered to me by my Father; and no one knows who the Son is except the Father, or who the Father is except the Son and any one to whom the Son chooses to reveal him (v. 22).

Often in the Gospels, when Christ associates Himself with the Father in such a way that He suggests that He, too, is divine, some scribe or Pharisee, that is, an expert on the Law and Prophets, get up in His face and interrogates Him. Just after His speech in v. 22, a “lawyer” “stood up” to put Christ to the test. The Greek for lawyer is nomikos, a scholar of the Law, Torah, especially first five books of the Hebrew Scriptures (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy). However, “Torah,” used more loosely, can also imply the whole of Scripture, with the Prophets and the rest, the Tanakh.

The lawyer “tested” Christ. Greek peirazō is “to test” or “tempt” and ekpeirazō is even more intense. In the dialogue of Christ with Satan during His temptation in the desert, Jesus told the Enemy, “You shall not put the Lord your God to the test (ekpeirazō)” (Luke 4:12). Paul tells the Corinthians, “Nor let us try (ekpeirazō) the Lord, as some of them did, and were destroyed by the serpents” (1 Cor 10:9). That’s a reference to Exodus, where there are many examples of the People lacking trust and needing proof from God, putting Him to the test, which brings chastisement. For example, at Massah/Meribah the people were thirsty and they grumbled against Moses. “They tested the Lord, saying, ‘Is the Lord among us, or not?’” (Exodus 17:1-7 with peirazō in the LXX). Hebrews 3, with peirazō, hearkens to this episode, which is recalled in the Invitatory prayer at the beginning of the Office every day. But in Luke 10 we have the rather provocative ekpeirazō, which to my ear sounds a bit like “goaded.”

The first part of their encounter is what one would expect of Jewish scripture scholars opening up a question.

Lawyer: “Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?”

Teacher: “What is written in the law? How do you read?”

This is not a dodge on the part of the Lord. Remember that ancient Hebrew texts were written without spaces, punctuation, or even vowels. They were strings of consonants. Make a different choice of vowels and you change the meaning. A good example of this is the word מלך… M-L-CH, with vowels E-E inserted, you have “melech” which is “king.” With vowels O-E you have “Moloch,” the Canaanite/Phoenician demon-god associated with child sacrifice.

The lawyer then answers with a combination of the famous of the first part of the “Shema… ” of Deut 6, God’s command to the people: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind” (v. 4-5) and the second part of God’s command in Leviticus 19:18, “you shall love your neighbor as yourself.”

Christ told the nomikos, “You have answered right; do this, and you will live” (v. 28).

You would think that that had settled the issue rather amicably, between scholars. But no. The lawyer was testing, tempting, goading. Also, he seems to have sensed something more in the Lord’s response than a theoretical or theological response, especially in that “Do this and you will live.” Obviously, “Don’t do this and you won’t live: rather ‘eternal death’ awaits.”

Our nomikos seems to take this personally. He wants to show himself as righteous, “to justify” himself, dikaióō, which in this context means, “to be guiltless of reproach, be acquitted of a charge.” He challenges:

“Who is my neighbor?”

This is a kind of “What is truth?” moment, followed with a rhetorical washing of his hands. He sparks the parable, by pressing the Lord like a lawyer. As if to say, “Of course I love my neighbor, but, after all, not everyone’s my neighbor, so don’t look at me! I quoted Leviticus! I take care of my own just as the command says!”

This is when Christ delivers the haymaker in the form of a parable.

Over the weeks and months of these columns you have – if you can struggle through them – seen that I keep bashing away about “context.” Also, I will urge people in preparing for the upcoming Sunday’s Mass to preview the orations and readings and even to read some verses before and after… for context. Just as a Hebrew vowel can make a difference, so can context.

The lawyer, in his original answer, quoted Leviticus 19:18b. There’s also 19:18a, the first part of the verse. There’s also, Lev 19:17 and other verses about how to treat and not treat one’s “neighbor” (רע “réa‘” as opposed to רע “ra” meaning “evil, wicked,” as in Genesis 13:13: “Now the men of Sodom were wicked, great sinners against the LORD.”) The whole of Lev 19:18 reads:

You shall not take vengeance or bear any grudge against the sons of your own people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself: I am the LORD.

Note well that “sons of your own people,” which seems to place a limit on “neighbor.” Christ heard what vowels the lawyer chose, so He knows he knows the text.

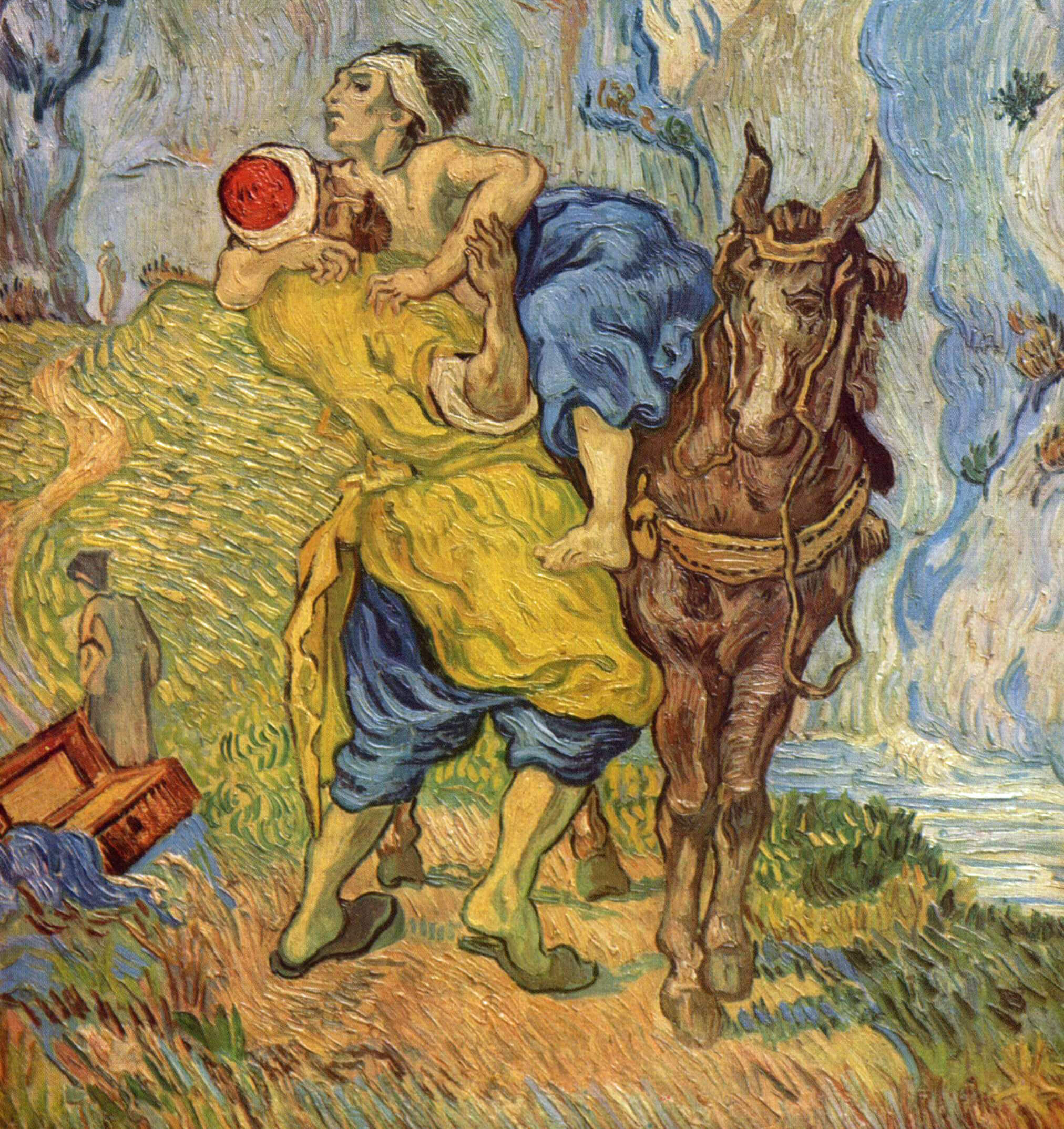

There follows the famous Parable of the Good Samaritan, so well-known that the image is used in common parlance by people who have not the slightest clue as to the context, Sacred Scripture and the teachings of Jesus. A new movie with Sylvester Stallone is out that proves my point.

You know the parable, and you will already have had your Bible opened as you read this, so you can recheck Luke 10:23-37, the only Gospel which records it. Here are some additional notes to help you glean more from it during Sunday’s full, conscious and actively receptive listening.

The dramatis personae include a Jew who is going down along the extremely steep and barren road from Jerusalem to Jericho in the valley of the Jordan River. He is mugged, badly, but not killed. Three people come along. The first two are men who performed their rounds of Temple service, as surely our nomikos had done, and are heading back to Jericho. One is a descendent of Aaron, a priest, and other a descent of Levi, a sort of deacon, a priest’s liturgical assistant. They go to the other side of the road to avoid the “half-dead” mugging victim.

By the way, it is often assumed that the priest and Levite – two guys like the nomikos who know the Law – go to the other side of the road because they were not to come within four cubits (roughly 1/10 of a Greek stadion or 6 Roman pedes) of a corpse or they would be ritually impure (cf. Leviticus 21:1-3).

The problem with that is the Lord’s own important details. The priest and Levite are going away, “down” from Jerusalem and the Temple. They are not restrained by the impurity issue that would prohibit service. Also, the man isn’t dead, he’s hēmithanēs … “half dead” (v. 30). There are signs of life. Moreover, it was the teaching of the rabbis in the Mishnah, which recorded traditions and interpretations of the Law going back to before the time of Our Lord’s earthly ministry, that a priest would not become ritually impure by contact with the corpse of a relative, but they could be made ritually unclean by neglecting a corpse. The idea being that just leaving a corpse in a public place, like a roadway, put many at risk of being defiled, not a good thing on a road used to go up to the Temple for your round of service.

This would have been known to the nomikos, the lawyer. Hence, Christ lead this lawyer down a steep path into a gentle mugging with the Truth.

The third man of our parable to come along is the one who provides the classic nimshal or unexpected twist. He is a Samaritan, and therefore considered by the Jews as both religiously and also ethnically impure. There was huge hostility between the Israelites and the Samaritans, who were the ethnically mixed remnants of the 10 northern Tribes scattered and relocated by the Assyrians in the 8th c. BC, who accepted only the five Books of Moses and worship differently on Mount Gerazim. They were largely seen as “gentiles.” What sort of hatred was there between the Jews and Samaritans? The 1st century historian Josephus says that some Samaritans once slipped into the Temple in Jerusalem at Passover and put human bones around the place, thus rendering the place and all the people ritually unclean… at Passover.

The Samaritan is the one who takes care of the wounded man, decidedly not a “son of his own people.”

Breaking down what the Samaritan did, he didn’t just feel bad for the poor guy (“he had compassion” v. 33), he did something concrete, along the lines of “do this, and you will live” (v. 28). To use perhaps familiar categories, the Samaritan gave of his “time, talent, and treasure.” Though in a hurry – he has some place he had to be, because he had to “come back” at some point (v. 35) – he spent his time, which in that barren place where people got mugged is not to be sniffed at. The less time you spend on that road, steep and bleak if you’ve been there, the better. He employed some skill in administering first aid. He gave up treasure, his food and perhaps pieces of his own clothing when he “bound up his wounds, pouring on oil and wine” (v. 34). He paid at the inn for the victim’s care and promised to spend more money, as well as time, by coming back and checking on him.

‘Which of these three, do you think, proved neighbor to the man who fell among the robbers?’ He said, ‘The one who showed mercy on him.’ And Jesus said to him, ‘Go and do likewise.’

The lawyer concludes that it was the hated Samaritan who demonstrates what “love of neighbor” really looks like, in concrete terms.

At the end of the parable, the Lord repeats, “Go and do likewise” (v. 37).

To summarize, Christ, Who when His public ministry began had been tempted by Satan (Luke 4:1-13, etc.), and who had just said, “I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven” (Luke 10:18), was tempted by a lawyer, whom Christ brought down to earth.

Fathers of the Church such as St. Augustine of Hippo (+430) had allegorical interpretations of parables. In this case, the Samaritan is Christ, the man half-dead is fallen humanity, and the inn is Holy Mother the Catholic Church, the place of refuge and healing.

Two points to conclude.

Anyone who, seeing the troubles within the Church, which Christ founded precisely as the place wherein we work out our troubles, thinks it might be a good idea to leave the practice of the Faith, “leave the Church,” is pretty much putting himself back on the road where he will get spiritually mugged, and, probably, spiritually dead.

The Samaritans and the Jews were enemies. Christ reveals a critical aspect of the obligation of love for and care for one’s neighbor. ou don’t just care for your own, you also care for your enemies. Sacrificial love is exactly that, exemplified perfectly on the Cross.

“Go and do likewise.”