|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

One thousand years ago, on April 19, 1024, Romano of the counts of Tusculum, brother of Pope Benedict VIII (†1024), was elected Pope with the name of John XIX.

At the time of his election, he was still a layman, holding the positions of “consul, duke and senator of all the Romans.” During his pontificate, he crowned as Holy Roman emperor the German king Conrad II (Easter 1027), involved himself in the conflicts between the patriarchal sees of Aquileia and Grado in northeastern Italy, and showed support for reformist positions, favoring the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny in east-central France. The details of his death, which probably occurred on October 20, 1032, are unknown.

Under Pope John XIX, Guido d’Arezzo (†1050), a Benedictine monk at the Pomposa Abbey, lived. Guido was known for his innovations in Western musical notation, before which the learning and transmission of liturgical melodies mainly occurred through oral memorization. The renowned music theorist,

at the bidding of the pope, came to Rome and produced his wonderful invention, whereby the ancient and traditional chants might be more easily published, circulated and preserved intact for posterity — to the great benefit and glory of the Church and of art. It was in the Lateran Palace that Gregory the Great, having made his famous collection of the traditional treasures of plainsong, editing them with additions of his own, had wisely founded his great Schola in order to perpetuate the true interpretation of the liturgical chant. It was in the same building that the monk Guido gave a demonstration of his marvelous invention before the Roman clergy and the Roman Pontiff himself. The pope, by his approbation and high praise of it, was responsible for the gradual spread of the new system throughout the whole world, and thus for the great advantages that accrued therefrom to musical art in general.[1]

It is Guido who, along with the fundamental principles of his music theory, recounts this episode, which perhaps took place in March 1027, in the Epistola Guidonis Michaeli monacho de ignoto cantu (also known as the Epistola ad Michaelem), to his fellow monk Michele of the Pomposa Abbey:

Summæ Sedis Apostolicæ Johannes, qui modo Romanam gubernat Ecclesiam, audiens famam nostræ scholæ, et quomodo per nostra Antiphonaria inauditos pueri cognoscerunt cantus, valde miratus, tribus nuntiis me ad se invitavit. Adii igitur Romam cum domno Grunvaldo reverentissimo Abbate, et domno Petro Aretinæ ecclesiæ Canonicorum præposito, viro pro nostris temporis qualitate sanctissimo. Multum itaque Pontifex meo gratulatus est adventu, multa colloquens et diversa perquirens: nostrumque velut quoddam prodigium sæpe revolvers Antiphonarium, præfixasque ruminans regulas, non prius destitit, aut de loco in quo sedebat, abscessit, donec unum versiculum inauditum sui voti compos edisceret, ut quod vix credebat in aliis, tam subito in se recognosceret.

The Supreme Pontiff of the Apostolic See, John, who now governs the Roman Church, hearing of the fame of our school, and how through our Antiphonaries unheard melodies were known to boys, greatly amazed, invited me to him through three messengers. Therefore, I went to Rome with the most reverend Abbot Grunvaldo and with Peter, superior of the Canons of the Church in Arezzo, a most holy man for our time. The Pontiff greatly congratulated me on my arrival, talking about many things and asking various questions: often reviewing our Antiphonary like something portentous, meditating on the prefixed rules, he did not move from his place until he learned, as he desired, a verse he never heard before, so that he recognized in himself what he could hardly believe possible in others (our translation).

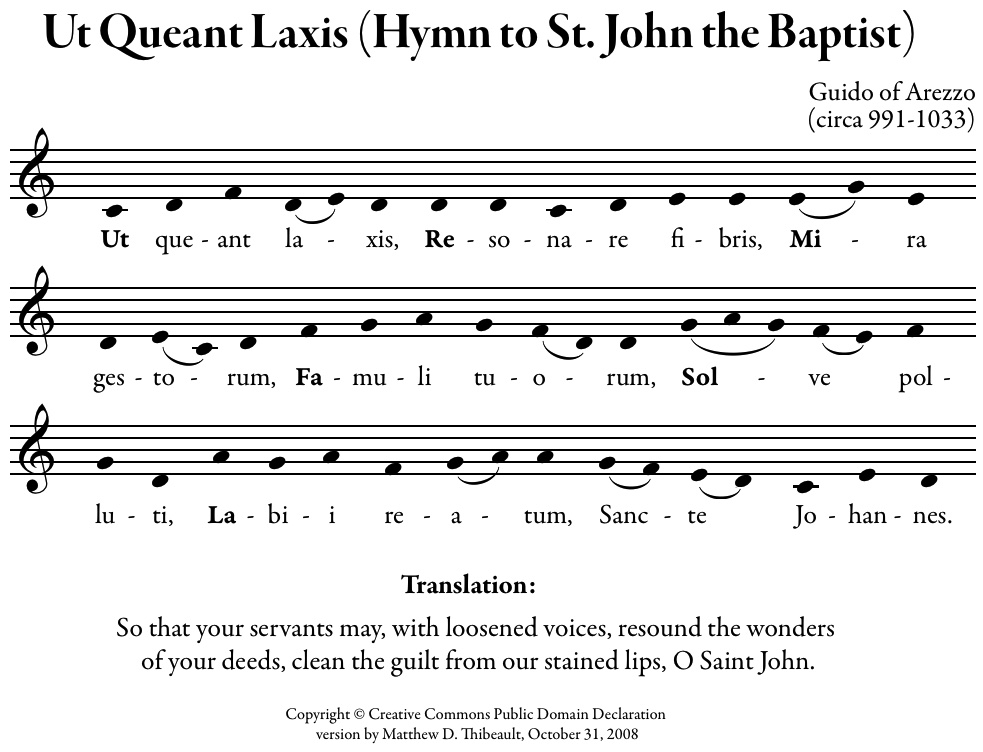

During the meeting, Guido showed the Pope his Prologus in antiphonarium, a small introductory manual to the liturgical chant books, written with the new notation system he promoted, explaining the principles on which it is based. The student had to associate the first syllables of the first stanza of the hymn to St. John the Baptist (UT queant laxis – REsonare fibris | MIra gestorum – FAmuli tuorum | SOLve polluti – LAbii reatum – Sancte Iohannes), lyrics by Paul the Deacon (†799) and melody perhaps composed specifically by Guido, to the sounds of an ascending scale of six notes (natural hexachord).

It was the Spanish mathematician and music theorist Bartolomé Ramos de Pareja (†1522) who introduced the “Si,” taking it from the initials of Sancte Ioannes in the last half-verse of the hymn, and Giovanni Battista Doni (†1647), a scholar and music writer, who changed “Ut” to “Do,” taking the first syllable from his last name.

With Guido’s method, the association between the syllables (Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La) and the intonation of the individual sounds remains firmly impressed in memory and can be recalled when necessary. By studying and becoming familiar with intervals, everyone could sing a written melody at first sight or transcribe it after hearing it.

Pope John XIX was fascinated by Guido’s educational innovations and invited him to return to teach at the renowned schola cantorum of the Lateran. This ecclesiastical school, which tradition holds was founded by Pope St. Gregory the Great (†604), was located in a monastery attached to the oratory of St. Stephen de Schola Cantorum near the Lateran Baptistery. The Lateran schola cantorum attracted boys from every country in Western Europe. Here, they studied music and classical culture, received minor orders (ostiariate, lectorate, exorcistate, and acolytate), and participated in solemn religious ceremonies and significant events in city life. Some historians suggest that Pope St. Leo II (†683) was a part of this school. Lateran schola cantorum’s influence on the development of medieval music and poetry is demonstrated by the fact that many collections of hymns and songs originated from it.

Perhaps John XIX was a “mediocre pope who did not fully understand the religious dimension of his office.”[2] However, amid criticisms of his pontificate, his fundamental role in supporting Guido d’Arezzo cannot be overlooked.

[1] Pio XI, Divini Cultus, December 20, 1928.

[2] A. Torresani, Storia della Chiesa, Milan 2018.