Part 2 of a 3-part Series. You may read the other parts here: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

Some readers might be wondering why the Church places such an emphasis on singing Gregorian chant in particular. Why this style and repertoire of music, in preference to others? And is it really true that the Church expects laity to sing the chant as well?

Saint Pius X, that hero of all traditionalists, wrote in his 1903 motu proprio Inter Sollicitudines:

These qualities [of holiness, good artistic form, and universality] are to be found in the highest degree in Gregorian chant, which is consequently the chant proper to the Roman Church … The ancient traditional Gregorian chant must, therefore, in a large measure be restored to the functions of public worship … Special efforts are to be made to restore the use of the Gregorian chant by the people, so that the faithful may again take a more active part in the ecclesiastical offices, as was the case in ancient times.

Pope Pius XI had this to say in his 1928 encyclical Divini Cultus:

Voices, in preference to instruments, ought to be heard in the church: the voices of the clergy, the choir, and the congregation. Nor should it be deemed that the Church, in preferring the human voice to any musical instrument, is obstructing the progress of music; for no instrument, however perfect, however excellent, can surpass the human voice in expressing human thought, especially when it is used by the mind to offer up prayer and praise to Almighty God. …

In order that the faithful may more actively participate in divine worship, let them be made once more to sing the Gregorian Chant, so far as it belongs to them to take part in it. It is most important that when the faithful assist at the sacred ceremonies … they should not be merely detached and silent spectators, but, filled with a deep sense of the beauty of the Liturgy, they should sing alternately with the clergy or the choir, as it is prescribed. If this is done, then it will no longer happen that the people either make no answer at all to the public prayers … or at best utter the responses in a low and subdued manner.

When Pius XI says “sing alternately with the clergy,” he means, for example, when the priest chants “Dominus vobiscum,” everyone responds: “Et cum spiritu tuo”; or, in the usus antiquior, at the end of the Pater noster, everyone chants together: “Sed libera nos a malo.” The point about alternating with the choir is seen in the Kyrie: the choir chants the first petition, then everyone chants the second petition, then back to the choir for the third, and so forth.

Venerable Pius XII writes very beautifully in his encyclical Mediator Dei of 1947:

A congregation that is devoutly present at that sacrifice in which our Savior, together with His children redeemed by His sacred blood, sings the nuptial hymn of His immense love, cannot keep silent, for “song befits the lover” (Saint Augustine, Sermon 336), and, as the ancient saying has it, “he who sings well prays twice.” Thus the Church militant, faithful as well as clergy, joins in the hymns of the Church triumphant and with the choirs of angels, and all together sing a wondrous and eternal hymn of praise to the most Holy Trinity in keeping with the words of the Preface: “we entreat that Thou wouldst bid our voices too be heard with [the angels’], crying out with suppliant praise.”

In his 1955 encyclical Musicae Sacrae, Pius XII added:

It is the duty of all those to whom Christ the Lord has entrusted the task of guarding and dispensing the Church’s riches to preserve this precious treasure of Gregorian chant diligently and to impart it generously to the Christian people. … In the performance of the sacred liturgical rites this same Gregorian chant should be most widely used and great care should be taken that it be performed properly, worthily, and reverently.

The conclusion we can take away from these papal documents—and there are more in the same vein than came after 1955, but every article must have its limits—is that we the people are repeatedly and directly asked by Holy Mother Church to SING THE MASS. It is our right; it is our duty; it is actually part of our sanctification and salvation. As Catholics who follow the Pope and the Magisterium, we should all be singing the chants of the Ordinary.[i] (Of course, exceptions can be made for special occasions, when a polyphonic Mass sung by the choir augments the people’s festive joy and gives a new impetus to their meditation on the mysteries.)

Now, you may ask, what’s all this praise of Gregorian chant? To borrow a saying from the world of the pipe organ, the popes certainly pull out all the stops when speaking about chant. But so does the Second Vatican Council, whose unambiguous witness on this point is all the more striking, given the almost total ignorance or repudiation of it in practice. Here are some highlights from the chapter on music in the Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium. While reading, note the surreal disconnect between what the Council peacefully teaches here and the lamentable universal practice throughout the Latin Church, which has behaved as if these words had never been written.

-

The musical tradition of the universal Church is a treasure of inestimable value, greater even than that of any other art. The main reason for this pre-eminence is that, as sacred song united to the words, it forms a necessary or integral part of the solemn liturgy. Holy Scripture, indeed, has bestowed praise upon sacred song, and the same may be said of the fathers of the Church and of the Roman pontiffs who in recent times, led by Saint Pius X, have explained more precisely the ministerial function supplied by sacred music in the service of the Lord. Therefore sacred music is to be considered the more holy in proportion as it is more closely connected with the liturgical action, whether it adds delight to prayer, fosters unity of minds, or confers greater solemnity upon the sacred rites. … Accordingly, the sacred Council, keeping to the norms and precepts of ecclesiastical tradition and discipline, and having regard to the purpose of sacred music, which is the glory of God and the sanctification of the faithful, decrees as follows.

-

Liturgical worship is given a more noble form when the divine offices are celebrated solemnly in song, with the assistance of sacred ministers and the active participation of the people. …

-

The treasure of sacred music is to be preserved and fostered with great care. Choirs must be diligently promoted …

-

Great importance is to be attached to the teaching and practice of music in seminaries, in the novitiates and houses of study of religious of both sexes, and also in other Catholic institutions and schools. To impart this instruction, teachers are to be carefully trained and put in charge of the teaching of sacred music. …

But these are just the preliminaries. Now we get to paragraph 116, and I am going to give you a more literal translation than the standard English translation you can find on the internet:

-

The Church acknowledges Gregorian chant as characteristically belonging to the Roman liturgy, with the result that, other things being equal, in liturgical actions Gregorian chant takes possession of the first place.

The phrase “other things being equal” means that even if we assume there is other music of equal artistic value and liturgical appropriateness, such as Renaissance polyphony, the chant still takes possession of the first place—and why? Because it is sacred, it is ancient, and it is ours, binding us intimately to God and one another with the ties of tradition. As Fr. John Zuhlsdorf comments on this paragraph:

If you aren’t praying with Gregorian chant, 50 years after the Council, then you are 50 years out of step with what the Council mandated in the strongest terms. The Council Fathers in Sacrosanctum Concilium go on to talk about the use of other kinds of music and they provide a welcome flexibility. But none of those other provisions eliminates or supersedes or mitigates what SC 116 says. In other words, we shouldn’t justify the use of Gregorian chant. The Church has done that for us. We have to justify the use of something other than Gregorian chant.

Vatican II was the first ecumenical council in the 2,000-year history of the Church to expressly name Gregorian chant as the music proper to the Roman rite and to establish officially its normative status and primacy of place. Why did the twenty earlier ecumenical councils not mention any of this? Because it had simply been taken for granted back then, whereas in the middle of the last century there was debate about whether it was time to substitute a different music for the traditional chant. Maybe “modern man” needed something else? And Vatican II’s answer was crystal clear: there can be no substitute. What modern man needs most of all is to be traditional and timeless, not trapped within the limits of his own age and its superficial tastes and assumptions.

Why, then, have so many people ignored what Vatican II asked for? That’s a very good question, and to answer it, one would have to enter into a separate discussion about the militant opposition between a hermeneutic of continuity and a hermeneutic of rupture and discontinuity, as our Pope Emeritus would say. But the historical ins and outs need not affect us, practically speaking, because we are trying to be entirely faithful to the Magisterium, and the Magisterium has always been consistent in its promotion of chant.

* * *

Let us dig deeper into why we sing what we sing at Mass, and what are the roles of the various people present. The Mass is a manifestation of the essence of the Church as the Mystical Body of Christ, therefore as hierarchical communion. That is why there are chants that only the ministers sing; chants that only a cantor or schola sings; and chants that everyone sings.

The parts sung by bishop, priest, or deacon are theirs by virtue of their distinctive sacramental identification with Christ, the Head of the Church, and therefore can never be sung by one who is not ordained. This shows us unambiguously that the ordained minister is not a mere delegate of the community, as in a modern democratic government or a Protestant community, but a true head and ruler of it, appointed by God.

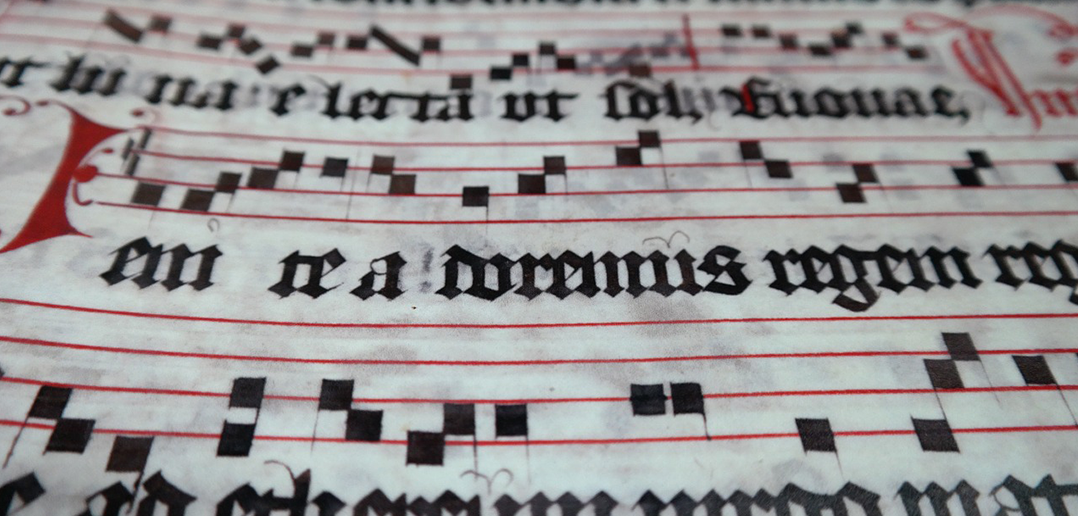

Then there are the “Propers” of the Mass, entrusted to the Schola, that is, the choir of trained singers. There are five such Propers: the Introit or Entrance antiphon; the Gradual; the Alleluia; the Offertory; and the Communion. (In Lent, the Alleluia is replaced with a Tract; in Paschaltide, the Gradual is replaced with an additional Alleluia.) These are an integral part of the Mass and have been such for over 1,500 years. In more recent times they have tended to be strangely forgotten, especially in the desert decades after Vatican II. Nowadays a great effort is being made to recover these Propers even in the sphere of the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite, so that the celebration of Mass might be more faithful not only to our tradition but also to the General Instruction on the Roman Missal, which specifies—for the Ordinary Form, mind you—the Gregorian antiphons from the Graduale Romanum as the preferred songs for the Entrance, the Offertory, and the Communion. This General Instruction, the official “how-to” manual for the Novus Ordo Missae, is a document promulgated by the Holy Father and is binding on the clergy. Once again, we see how traditionalist communities are pointing the way to the correct implementation of the very rubrics and rules of the Ordinary Form itself!

Sometimes you will encounter Catholics who are offended when a choir sings chant or polyphony and they cannot join in but must simply listen. They object that they are supposed to be “actively participating” and how can they do this in such a situation? Blessed John Paul II responded to this objection in a very important address he gave back in 1998. I believe that this paragraph should be engraved on a plaque and displayed in the vestibule of every church:

The liturgy, like the Church, is intended to be hierarchical and polyphonic, respecting the different roles assigned by Christ and allowing all the different voices to blend in one great hymn of praise. Active participation certainly means that, in gesture, word, song, and service, all the members of the community take part in an act of worship, which is anything but inert or passive. Yet active participation does not preclude the active passivity of silence, stillness and listening: indeed, it demands it. Worshippers are not passive, for instance, when listening to the readings or the homily, or following the prayers of the celebrant and the chants and music of the liturgy. These are experiences of silence and stillness, but they are in their own way profoundly active. In a culture which neither favors nor fosters meditative quiet, the art of interior listening is learned only with difficulty. Here we see how the liturgy, though it must always be properly inculturated, must also be countercultural.

In the last article of this series, I will look at some more practical issues: how chant should be sung, and what we are to make of the excuses people give for not singing.

NOTES:

[i] One could quote extensively from John Paul II and Benedict XVI. Fortunately Ratzinger/Benedict is well known for his many writings on sacred music and authentic liturgical participation, whereas the preconciliar Magisterium is often neglected nowadays.