|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

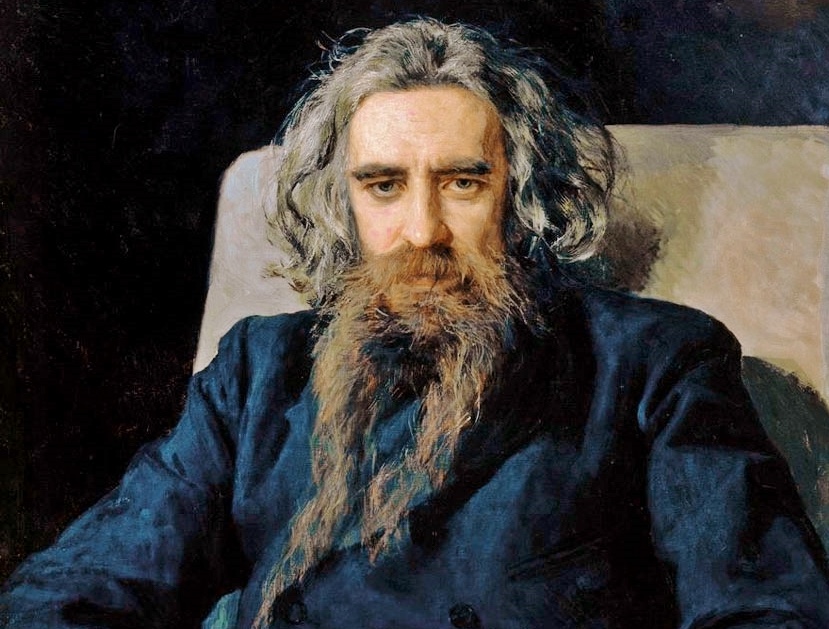

Who is Vladimir Solovyov?

In the realm of Russian philosophy, there stands a figure as towering as the great cathedrals of old Moscow – the city that carried and nourished the man whose name was Vladimir Solovyov. A thinker of profound intellect and spiritual insight, Solovyov was the first systematic Russian philosopher who formed the ground for international humanistic psychology and Christian humanism of the 20th century in general. He also provided the Russian religious thinkers and those who were eventually influenced by them in Europe with strict phenomenological tools to criticise modern godless philosophy that disrespected man and reduced a human being to a social or biological function. He used a method of phenomenological analyses before Husserl and was the Christian Jordan Peterson of his time, defending all things good and meaningful in front of growing nihilism.

Nobody in Russia would argue against these first words. Also, these are pure facts that unite me, a Russian Catholic, with my Eastern Orthodox compatriots who would see me as a traitor in many other questions. There is another set of facts, though, that is just as true as divisive. After a life-long record of pro-Catholic thought and publications, it was on February 18, 1896 when Vladimir Solovyov, the greatest Russian philosopher, officially became an Eastern Catholic.

He was received into full communion with Rome by a Russian Byzantine Catholic priest, Fr. Nikolay Tolstoy, in the presence of two lay people – Princess Olga Vasilievna Dolgorukova and Mr. Dmitry Sergeevich Novskiy.

I shall provide for this article a personal translation of the full testimony of those witnesses, originally published in ‘Kitezh’ journal[1]:

The act of conversion of Vl[adimir] Solovyov to Catholicism.

In view of the continuing doubts in our domestic and foreign press as to whether the late philosopher and religious thinker Vladimir Sergeevich Solovyov was canonically attached to the Catholic Church, we, the undersigned, consider it our duty to declare in print that we were witnesses – indeed eyewitnesses of Vladimir Sergeevich [Solovyov]’s admission into the Catholic Church, committed by the Greek-Catholic priest Fr. Nikolay Alekseevich Tolstoy on February 18 (Julian calendar) 1896 in Moscow, in a home chapel arranged in a private apartment of Fr. Tolstoy that is located in Ostozhenka, Vsevolozhsky Lane, in Sobolev’s house. After a confession heard by Fr. Tolstoy, Vladimir Sergeevich [Solovyov] read the Tridentine Creed in Church Slavonic in our very presence, and then at the Liturgy celebrated by Fr. Tolstoy, according to the Greek-Eastern rite (with the commemoration of the Most Holy Father – the Pope), he received Holy Communion. Apart from us, this memorable event was attended by only one other Russian girl, who was in the service of Fr. Tolstoy’s family, whose name and surname unfortunately cannot be recalled at the present time.

By publicly bearing our present testimony, we believe that it must put an end to all doubts on the above mentioned question once and for all.

Priest Nikolay Alekseevich Tolstoy

Princess Olga Vasilievna Dolgorukova

Dmitry Sergeevich Novsky.

Who were these people who witnessed the conversion and signed publicly their testimony?

Nikolai Alexeyevich Tolstoy (1867-1938) was the first Russian Orthodox priest to convert to Catholicism in modern history. In December 1894, he arrived in Rome as an Orthodox priest and signed a confession of the Catholic faith before Pope Leo XIII – the great pope who defended the East and wrote Orientalium Dignitas – an encyclical that changed that once hostile and arrogant attitude of the Latin Church towards the Eastern rites, setting the stage for Vatican II’s most glorious Orientalium Ecclesiarum. Fr. Tolstoy wrote an article titled ‘Vladimir Solovyov – a Catholic,’ where he reported Solovyov joining the Catholic Church of the Eastern Rite in 1896 – two years after his own conversion to the one true faith. For Fr. Tolstoy, it was an act of personal importance, because it was Vladimir Solovyov whose works influenced Fr. Tolstoy himself, forming and leading him to full communion with the Catholic Church.

He also wrote on that very event, mentioning the two other witnesses:

‘Upon returning to Moscow, I resumed my daily services. Before the Maslenitsa[2] of 1896, Abbot Vivian introduced me to a lady who wished to convert to Catholicism. She turned out to be the daughter of the Vilnius Governor-General Dolgoruky. She had long been considering this step and was well-prepared by Latin priests, who, however, were afraid to accept her conversion themselves. Father Vivian directed her straight to me, explaining that she should remain in the Eastern rite. The dean of the Polish church, Father Otten, warned me to beware of the anger of this lady’s father. But Father Vivian was now my spiritual advisor, and if he deemed it necessary, I saw no reason to refuse. Though I wondered why he had dissuaded the Solomirskys, who were neither dangerous nor faced any danger themselves. And so I accepted her, she confessed and received communion from me, and then began attending services regularly.’[3]

The noble lady’s name was Olga.[4]

Princess Olga Vasilievna Dolgorukova belonged to the oldest aristocratic family, connected to the Rurikid dynasty, the first ruling dynasty of Rus’ and then Russia, which can be compared to the pre-Norman kings of the Anglo-Saxons. The same year of her own becoming a Catholic, Princess Dolgorukova became a witness to Solovyov’s conversion to Catholicism.

In the same piece, Fr. Tolstoy writes about the second signee witness.

Dmitry Sergeyevich Novsky (?–1918) was a Russian Catholic who was ordained as a subdeacon in Galicia and worked as a Latin language teacher in Yaroslavl.[5]

The Great Lent arrived, then Novsky and I began performing all services according to the regulations. In the second week, Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov visited me, and I was deeply moved by the fact that I had to hear the confession of faith and admit into communion of the Catholic Church my own teacher, who had led me to it.[6]

Thus, Vladimir Solovyov was indeed a Catholic.

Ok, he made an act of conversion, but was he serious about it?

It is an argument about the intention.

None of the contemporary critics would directly accuse the priest and the two lay witnesses with a noble woman among them of lying. However, it was still a bitter red pill to swallow for the Russian Orthodox community, as it has been ever since.

According to a popular Russian Orthodox hypothesis, Vladimir Solovyov’s conversion was not valid or serious, because he did not denounce Eastern Orthodoxy and was odd to both sides, vaguely remaining some kind of Orthodox Ecumenist.

Among the adherents of this criticism were the Russian philosopher Nikolai Lossky[7] and the literary critic Konstantin Mochulsky, who wrote a whole book about Solovyov and engaged in polemics, trying to find enough reasons to refute Solovyov’s Catholicism. As mentioned above, these bright minds tried to do everything to ‘justify’ Solovyov as uninvited advocates precisely because they considered him their forefather and a great master. They were not bad people, far from it.

Besides, another great Russian philosopher Evgeniy Nikolaevitch Troubetzkoy wrote about the philosopher’s views:

Solovyov considered it possible to be completely Catholic, without ceasing to be at the same time completely Orthodox. He simply denied the very fact of the actual division of the churches, admitting that the division exists only on the surface and does not concern the very inner essence of church life… he categorically declares “that… Russian religion, if we understand by this term the faith of the people and worship, completely Orthodox and Catholic.”[8]

Having said such words, could he really be serious about the conversion? What is conversion for if there is no schism and we are already in union?

Indeed, Solovyov’s works reveal many arguments to back this ‘ultra-ecumenical’ hypothesis about an extravagant and heterodox, yet Orthodox philosopher or a ‘schism-denier,’ which practically mean the same. For a long time, Solovyov did not support the idea that a formal act of personal conversion to the Catholic Church was necessary for a Russian Orthodox believer. He used to believe that the unity had existed forever despite all the schismatic factors and historic discrepancies. However, Solovyov did eventually change his opinion over time and converted to Catholicism. Formally and explicitly. And this act was prefigured by the development of Solovyov’s own thoughts.

Prior to taking this fundamental step, Vladimir Solovyov wrote his famous trilogy titled ‘Russia and the Universal Church,’ in which he laid out in detail the theoretical foundations for the need to restore ecclesiastical unity with the See of Peter – the foundations quite harmonious with his more general philosophical stance and consistently held up to the day he passed away.

The book includes the following:

As a member of the true and venerable Eastern or Greco-Russian Orthodox Church, which does not speak through a non-canonical synod nor through the employees of the secular power, but through the utterance of her great Fathers and Doctors, I recognise as supreme judge in matters of religion him who has been recognised as such by St. Irenaeus, St. Dionysius the Great, St. Athanasius the Great, St. John Chrysostom, St. Cyril, St. Flavian, the Blessed Theodoret, St Maximus the Confessor, St. Theodore of the Stadium, St. Ignatius, etc. etc. — namely, the Apostle Peter, who lives in his successors and who has not heard in vain our Lord’s words: ‘Thou art Peter and upon this rock I will build My Church’; ‘ Strengthen thy brethren’; ‘Feed My sheep, feed My lambs.’[9]

As you can see, already in this introduction to his Uniate magnum opus, Solovyov presents an ecclesiological argument in favour of papal primacy and declares his personal adherence to this doctrine by virtue of the authority of the Fathers. Of course, the book itself mostly focuses on the relationship between the Churches, but these thoughts of Solovyov cannot be characterised either as ‘Orthodox’ (as opposed to Catholic) or indifferentist in the spirit of the High Church Anglican Theory of branches. It is impossible to ignore this pro-Catholic and de facto Catholic theoretical foundation, making sense of the attested fact of Vladimir Solovyov’s conversion to the Catholic Church not only ‘in spirit,’ but quite ‘in flesh,’ in compliance with all required procedures at that time.

Here is what Fr. Tolstoy has to say on the matter:

And so, on the second week of Lent, February 18, 1896, in a small chapel of the Our Lady of Lourdes in Moscow, on Ostozhenka, in Vsevolozhsky Lane, near Sobolev’s house, next to my apartment, did this modest celebration take place. In the presence of members of my family, a priest and some individuals from the noble society of St. Petersburg and Moscow, a close circle of the convert’s admirers (whose names I am not yet authorised to disclose), Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov joined the Catholic Church, but without renouncing Orthodoxy, by simply confessing the ‘symbol of the Orthodox faith of the Tridentine Council, confessing and publicly receiving communion from the Uniate altar.[10]

We return to the realm of facts: the formal conversion did take place. The next ‘formal’ question remains:

Was Solovyov’s conversion valid or perfect without denouncing that ‘schismatic Eastern Orthodoxy?’

This argument is targeted on the ‘legal’ and formal validity of the act, although it is based on the previous question about Solovyov’s intentions and also implies it. Let us go to the point.

In our time, no Catholic priest can demand that a convert from other Christian churches should renounce heresy or schism. After all, only an apostate who has left the Catholic Church publicly or without announcement can be personally guilty of heresy or schism. Was the end of the 19th century more severe? According to the active participant in the Russian Catholic cause, Father Cyril Korolevsky, who took part in the investigation of this matter in 1896, Rome’s requirements regarding ‘Orthodox non-Catholics’ who converted to ‘Catholic orthodoxy’ did not differ from the norms of the first half of the 20th century.[11]

A convert was required to make a Catholic confession of faith. It was also necessary to lift excommunication from that person, as all non-Catholics continued to be seen as excommunicated because of the sin of schism. Nothing more was required even then, and the lifting of excommunication as a canonical act was done by the Church upon reuniting and with no further requirements from the convert. Therefore, no formal renunciation of Eastern Orthodoxy was even necessary! Moreover, it would have been theologically dangerous, as the Catholic Church recognises – which has been especially emphasised since Leo XIII – that the Eastern Churches possess a significant portion of the Catholic tradition and thus have value not to waste or disregard in any manner. In this sense, Vladimir Solovyov was quite Catholic in his concept of ‘perfection’ as opposed to ‘changing faith,’ even anticipating the theology of the Second Vatican Council in the last years of the 19th century. Truly, he was a genius.

Why do some commentators and participants in the discussion in the past and in our time alike believe that such an act of renouncement should have taken place? Because since the 18th century, the Russian Orthodox Synod (which Solovyov rightfully called ‘non-canonical’) established a rite for receiving Catholics into Russian Orthodoxy. This rite[12] was filled with thorough questioning that resembled a court interrogation and demanded renunciation of all Catholic teachings that were unlawfully considered heresies, despite the fact that no Ecumenical Council (even from the perspective of Eastern Orthodoxy) has ever condemned any ‘Catholic heresy’ in the entire history of this schism. The last time this awful rite was publicly used on record was during the apostasy of former Jesuit Konstantin Simon, a former professor at the Pontifical Oriental Institute, who shamefully went into schism and now lives in Russia. ‘I renounce… I renounce… I renounce…’ – said a former Jesuit in broken Church Slavonic with a heavy English accent before the congregation…

All Russian commentators were aware of this rite, as they generally do now, so no wonder they imagine the opposite conversion to be similar. What they did not and still do not realise is that the Catholic Church has a wiser and more charitable view on the matter, not requiring any special renunciations from her prodigal grandsons, her lost sheep – sheep from another fold of Jesus who come to the full communion under one shepherd.

Ok, Vladimir Solovyov became a Catholic. But was he a good Catholic?

Usually, when acknowledging the obvious fact of Solovyov’s conversion to Catholicism, Orthodox critics want to downplay this fact by portraying him as a bad member of the Universal Church. A half-hearted Catholic. A heretic mostly. It is interesting that this logic only kicks in after the forced acknowledgment of the very fact that he actually converted. If Solovyov had truly remained Russian Orthodox (in a common canonical sense), no one would have remembered those facts and circumstances, thoughts and theories that might have been quite extravagant, scandalous, interesting, or unacceptable to both Catholics and Orthodox then and nowadays.

Yes, when a young man, Solovyov was fascinated by spiritualism, the search for secret knowledge, and various Gnostic theories and concepts close to theosophy. Unfortunately, that was the culture and intellectual environment of that time.

Yes, even after joining the Catholic Church, Solovyov believed that a Christian’s conscience stands above all papal decrees and church circulars. He valued spiritual freedom to the point that the fake dilemma of ‘Papacy vs. Spiritual Freedom’ would have got a certain answer in favour of the latter[13], if anybody had asked Solovyov directly, which nobody actually did. Yet again, like many dichotomies of any national European discourse of modernity, the whole dilemma of ‘Popery vs. Freedom of Conscience’ has always been fake and far-fetched: the Catholic Church herself puts a properly formed conscience of a person above formal submission to any external structures and lawful authority. She does it by teaching her flock to act according to their conscience. She does not even judge the internal motives of a person, mitigating or even abolishing punishments for those irresistibly mistaken who act out their conscience to the best of their ability. ‘Papism’ within the delusional framework of the Slavophile[14] discourse is a strawman, something caricaturish and tyrannical. It has nothing to do with how the Papacy ought to work in Catholicism. Why on earth should Solovyov have chosen to defend this idol? Instead, he emphasised freedom while factually choosing for Catholicism, for Papacy, for the Union.

Here comes another strawman. Orthodox commentators like Mr. Mochulsky think that Solovyov remained absolutely Orthodox after his formal conversion by saying, for example, that not the hierarchy, but the entire body of the faithful is the infallible guardian of the truth. Indeed, but that is why Solovyov was absolutely Catholic: Sensus Fidei Fidelium – the sense of faith of the faithful – does not go against the hierarchical principle of the Church. This was the case even before the Second Vatican Council, although, of course, Vladimir Solovyov himself would have liked the accents made in Lumen Gentium 12 more than any manual written in the style and language of Cardinal Bellarmine (who, nonetheless, would agree that the infallibility of the Church, playing out differently in different levels of her structure, dwells on her entirety).

It is also true that Solovyov thought it was possible to be saved in all Christian Churches, as if the borders between them somehow did not reach the Heavens. That is why he himself ironically (as I would insist) once called himself ‘more Protestant than Catholic.’[15] But at the same time, he realised that it is the Catholic Church that was true and unique among all others – this thesis being central in his entire life and teachings. The Orthodox theologians of the time learnt well from the Latins that outside of the Church there is no salvation [‘extra Ecclesiam nulla salus.’] But unfortunately, like amateur counterfeits, they made a rough copy of that patristic truism. Their version is very similar to the marginal rigorist views of excommunicated Jesuit Fr. Leonard Feeney: all non-Catholics, regardless of their knowledge or intention, go to hell if they die outside of the Church’s visible borders. If those Eastern counterfeits had learned more from pre-Vatican II textbooks or even from the Catechism of St. Pius X[16], or had they read more their own Church Fathers, they would have had less problems understanding both Solovyov and actual Catholic theology. If only those Orthodox polemicists of the 19th century had done their homework, their modern offspring would now be more accepting of what Vatican II and Benedict XVI had to say on the matter – that teaching with which Solovyov would definitely have agreed.

Why was Solovyov not willing to participate in Latin Liturgies, if he was so Catholic?

I understand that a modern Catholic may find it strange that Solovyov was fundamentally opposed to participating in Latin services. He might seem intolerant or secretly heterodox. To understand his position in the right manner, one needs to delve into the historical context and the landscape. What did Solovyov see in terms of church-rite relations? Rite and faith were de facto considered synonyms, not to mention confessional and national identity of a person during that spring of newly formed nations in the European continent of the 17th to 18th centuries and later. Almost no one thought that within one Church there could co-exist equal traditions. About two hundred years before the Philosopher was born, the Latinisation of the Uniate rite began in the territory of the Polish-Lithuanian state inhabited by Eastern Slavic Uniates. When these lands of modern western Belarus and Ukraine passed to the Russian Imperial crown, it promoted this Latinisation of Eastern Catholics even further, suggesting: ‘If you want to be Catholics, be like the Poles. Go to the Latin Mass. And then we will tolerate you as ethnic minorities. If you want to serve in an Eastern way, be Orthodox, like normal Russians.’ Naturally, all Russians who converted to Catholicism were considered “Polonised,” as if they had renounced their roots and national culture. Vladimir Solovyov, being a genius, protested against this narrow-minded system and generally wanted to show throughout his entire life that one could be truly Catholic while remaining truly ‘Orthodox’ in the most popular sense of the word: in spirituality, prayer, history, and the way of holiness, i.e., as an Eastern Catholic (in modern classification).

Why then did Solovyov not call the Russians for mass conversion to Catholicism?

It remains to be noticed that Vladimir Solovyov never called for a mass conversion of Russians to Catholicism, expecting unity to triumph at the level of the Сhurches, although he joined the Catholic Church himself.

However, it is also true that

a) at that time there were no structures for Eastern Catholics in Russia, while mass Latinisation would have contradicted his beliefs and eventually the will of Rome and was also practically impossible;

b) mass and loud ‘proselytism’ could push the perspective of the ecclesiastical unity to an indefinite lane, for the push back would have been severe. The same opinion was a bit later held by Blessed Leonid Fedorov, a convert and a confessor, who is by no means to be reproached for insufficient Catholicism.

Bl. Leonid Fedorov was more into personal care and aid for conversion than Solovyov. Indeed, there were more zealous preachers and missionaries among his disciples than the philosopher himself. After all, Solovyov had no obligation or responsibility for the souls, being a lay thinker, whose entire life was dedicated to smart creation of all the necessary settings for the union between all the Churches under the See of Rome.

Much more can be said about this or that thought or stance of Vladimir Solovyov. But here is the most important thing. Any Catholic, especially a newcomer, can be right or wrong on many issues. It is only important for a Catholic to strive to listen to the Church’s pastors, not speaking out consciously and publicly against the dogmas and teachings of the Catholic Church. In this sense, which equally applies to all of us, Vladimir Solovyov was a good Catholic with his own theological and philosophical peculiarities and personal problems. In that same state, he died in 1900 in his private estate near Moscow.

But even in this question, cultural differences and jealousy will prompt some Orthodox authors to disagree.

Did Solovyov, who did not denounce his Orthodoxy, denounce his conversion to Catholicism when he was soon to die?

Some Orthodox speakers think so. Why? Because, right before his death Vladimir Solovyov received the absolution and the Holy Sacraments from an Orthodox, not a Catholic priest. This fact gives a reason to speculate that he might have changed his mind and returned to Eastern Orthodoxy, renouncing by doing so his ‘Popish experiments.’

There are two answers to this supposition.

The Geographical Answer is no.

Solovyov died in the Uzkoye estate. Should one visit this place on the outskirts of modern Moscow and far outside of a late 19th century borders of the city, it would become clear that an Orthodox church is within walking distance from the maison, while there is and was no Catholic chapel in many hours of horse ride, even if Vladimir Solovyov would be willing to call for a Latin Catholic priest – something he had never done in his life of a byzantine liturgical purist.

Just like today, even in those days, a faithful Catholic did not need to be as philosophically exceptional and theologically extravagant as Vladimir Solovyov in order to receive the ‘schismatic’ Holy Communion in the danger of his or her own death. Neither was such a faithful obliged to abstain from an absolution given by a schismatic priest in those circumstances, for the Sacraments always belong to the Catholic Church substantially and are never fundamentally schismatic, if only valid; while the principle law of the Church always remains the salvation of souls.

The Historical Answer is also no.

Any speculation around Solovyov’s alleged renunciation of the Catholic Church, apostasy, and return to Eastern Orthodoxy relates in one way or another to the last three years of his life when he was seriously ill, as well as to the two visits paid to him by two Orthodox priests, when they came to his final place on earth.

The First Visit

A year after his attested and well-established conversion to Catholicism, having just fallen seriously ill, Vladimir Solovyov invited an Orthodox priest, his former teacher at the Theological Academy and a scholar named Fr. Alexandr Ivantsov-Platonov for a confession.

This visit was witnessed by Solovyov’s family and personal friend, Ekaterina Eltsova. She writes in her memoirs the following:

[Father] Ivantsov-Platonov was with Vladimir Sergeevich [Solovyov] for a very long time, and spoke with him long; nevertheless, leaving him, he said that he had not given him Holy Communion, that, apparently, there was nothing threatening in his condition, and since Solovyov had eaten something in the morning, they postponed his receiving Holy Communion. Alexander Mikhailovich [Fr. Ivantsov-Platonov], a man of great intelligence and amazing kindness, one might say, even holiness, left him as if preoccupied and oppressed by something. So, at least it seemed so to me. We were completely satisfied with that explanation at that point.[17]

Was it a bit extravagant from the point of view of a ‘normal’ Latin Catholic or a hereditary Uniate from Ukraine to invite an Orthodox scholar priest for such a need? It might have been, as there was no deadly urgency yet. But can one argue it was sinful? The necessary circumstances to get an answer will soon be clarified.

The Last Visit

After the philosopher’s death, madam Eltsova came across a testimony of another Orthodox priest named Fr. Sergey Belyaev – a pastor from a nearby parish who had heard the last confession of Vladimir Sergeevich Solovyov right before he passed away.

This testimony was published in No. 253 of Moskovskie Vedomosti magazine, Wednesday, November 3 (16), 1910. The article containing it was suggested by another member of the Orthodox clergy, Fr. Kolosov, who designed and presented this piece as an ‘answer to the testimony of the former priest [Nikolay] Tolstoy about how he gave Holy Communion to the late Russian philosopher Vladimir Sergeevich Solovyov according to the Uniate rite.’[18]

Fr. Belyaev’s retold testimony reads as follows:

Vladimir Sergeevich [Solovyov] confessed with true Christian humility (the confession lasted at least half an hour) and, by the way, said that he had not been to confession for three years, since, during his previous confession (in Moscow or St. Petersburg – I don’t remember), he argued with the confessor on a dogmatic issue (on which one, Vladimir Sergeevich [Solovyov] did not say) and was not allowed by him to receive Holy Communion.

It was after reading this testimony, when Ekaterina Eltsova – the lady who witnessed this first visit – compared her memories with that story and asked herself the question whether the ‘theological argument’ described in it took place the day Fr. Ivantsov-Platonov visited Vladimir Solovyov and left him without Communion in a bad mood (First Visit).

This moment of seeming realisation added credibility to Fr. Belyaev’s testimony, which concludes with details:

‘The priest was right,’ – added Vladimir Sergeevich [Solovyov] – ‘and I argued with him solely out of my vehemence and pride; after that we corresponded with him on this issue, but I did not want to give up, although I was well aware that I was wrong; now I completely recognise my error and sincerely repent of it.’

From this testimony, which so utterly violates the secrecy of confession, an Orthodox polemicist will rush to the conclusion that Solovyov renounced his Catholicism right on the verge of death during the Last Visit.

And no wonder why: Fr. Kolosov’s article in which he retold Fr. Belyaev’s memories was literally set up to support the corresponding narrative:

a) Solovyov argued with an Orthodox theologian;

b) was denied Communion never to receive it for three following years;

c) and finally repented, receiving the Last Sacraments from another Orthodox priest, stating that he had been wrong, and the first Orthodox priest had been right about some dogmatic question.

This sounds convincing for somebody of a Russian Orthodox canonical culture in which, for a couple of centuries, it had been impossible to think of receiving any Sacraments without converting to the Church and Faith of the assisting priest. But there is a serious common-sense objection:

When you repent seriously of something that has occupied your whole personal and academic life, barely do you talk about this matter – whether it is adherence to heresy or a riotous lifestyle – among other things and as if indirectly. All the native Orthodox Christians, including Vladimir Solovyov, would know exactly that sins should be properly named without any mitigation or concealment. The obligatory instruction, read by the priest before confession and directed to those who want to receive absolution, contains the following words: ‘If you hide anything from me, you will commit a grave sin.’

That is, should one repent his or her conversion to Catholicism (that is perceived as nothing short of apostasy) and come back home, the words ‘apostasy’, ‘treason’ or ‘heresy’ shall be pronounced. There is no way around it. Had they been pronounced by Solovyov, the whole world would have known that, because that particular priest was perfectly willing to risk his salvation by violating the confidentiality of confession even for the sake of much less information. But Solovyov has only been known to have confessed two sins – pride and vehemence. Neither of them is reminiscent of leaving one’s own Church and becoming a Catholic.

What could the dispute with Fr. Ivantsov-Planonov, a friend and teacher, have been about?

Even Mr. Mochulsky, who collected all the evidence about the life and death of Solovyov and is the last person to suspect of holding to a pro-Catholic perspective suggests the following explanation as the most probable:

During the First Visit confession, Vladimir Solovyov might have told his close friend Fr. Ivantsov-Platonov about his conversion to the Catholic Church. The priest might have explained to the philosopher that, from the canonical point of view, he was a Uniate, which made it unlawful for an Orthodox priest to give him Holy Communion. Solovyov saw his Conversion in a different way – neither as an apostasy, nor as any kind of ‘exclusion’ from the Russian Church, while becoming fully Catholic. The philosopher might have insisted on an intercommunion and was probably denied it – especially with no threat of immediate death at the moment. Three years later, Solovyov realised that, morally and canonically, his priest-friend was right, and he shouldn’t have got angry at him, insisting on his thoughts about how the inter-ecclesiastical relations ought to work.

For three whole years, he seems to have lived without receiving the Holy Sacraments. He did not want any Latin priest around, and only before his death did he receive the last Sacraments from the nearest Orthodox priest, Fr. Sergiy Belyaev who, having listened to Solovyov for at least half an hour, proceeded to break the seal of confession in order to reveal that the philosopher Vladimir Solovyov was extremely sorry for converting to Catholicism? No. He was sorry for being rude to his friend and proud in his attitude to the canon laws or some theological question an Orthodox would classify as dogmatic.

Indeed, there is little difference between the terms ‘dogmatic’ and ‘theological’ in the Orthodox discourse compared to the Roman Catholic one, but the fact that apostasy, if realised, should have been denounced directly and very explicitly, helps to understand the approximate mildness of the matter, unless one would assume that Fr. Belyaev and many other people were wrong and Solovyov died in bad conscience.

But why – goes the last argument of those who stubbornly refuse to let Solovyov go from Orthodoxy to the Catholic Church he wrote so much about and publicly converted to…

Why did Solovyov not publicly declare his Uniate status, Catholic faith and philosophy right at his last confession in front of Fr. Belyaev?

Although this last question might sound too desperate to be taken seriously, one may think of two reasons:

Reason one. You should talk about sins and sins alone during your confession, not virtues;

Reason two. It was only in 1970, when the Russian Orthodox Church decided to officially allow (in exceptional cases, like, in the absence of the relevant clergy) giving Holy Communion to Catholics. Besides, this decision has never been ratified ever since. Thus, if Solovyov had begun to boast or simply declared his views to the Orthodox priest unknown to him, there was a good chance that he would not have been given Communion or even that he would have repeated the emotional quarrel, committing thereby another sin he would never be able to confess before death. Why should he have been willing to take a risk, about to stand before the Almighty God?

A Factual Conclusion

Although it is understandable why some Russian Orthodox thinkers are still in denial about Vladimir Solovyov’s conversion to Catholicism, being or dying a Catholic, or all three at the same time, all the evidence rather suggests that the philosopher did not renounce his pro-Catholic ideas and personal Catholicism to the end of his life. While some of his unusual views and attitudes only had to be fully articulated, clarified and corrected in Catholic theology in the coming century (when some of them were recognised at the highest level), the idea of the union with Rome played the most significant role in the life of Vladimir Solovyov – a great philosopher and an actual Russian Catholic till he took his very last breath on his native soil.

A Pastoral Reflection

Having said that, I do not hope that this article succeeds in making a definitive argument. It seems hardly possible, partly because the Orthodox and Catholic paradigms still differ too much, partly because one will only be able to talk to Solovyov and know the whole truth on the day of Final Judgment, but also because it might go against the Divine providence. A good friend of mine recently talked with his local Latin pastor about C.S. Lewis. The priest mentioned that perhaps the Lord in his providence didn’t give that great Christian writer the grace to become Catholic, because if he had publicly converted, none of the Protestants would even touch his books, while today many read him and draw closer to the idea of an apostolic church. I do agree that something similar may be at work with Solovyov, as this confusion of ‘unwillingly shared ownership’ allows both sides to claim him and read his works that undeniably lead Russians to the Universal Church, and the Western Catholics to love and pray for my country in this intention.

[1] No. 8-12, December 1927, Warsaw cited from Мочульский К.В., Владимир Соловьев. Жизнь и учение, полемизируя с Розановым, URL: http://www.vehi.net/mochulsky/soloviev/14.html#_ftn5

[2] Lit.: ‘Butter week,’ a Russian 7 day analogue of the Fat Tuesday carnival before the Great Lent, when meat is already prohibited, but the faithful are encouraged to feast on all things made out of milk.

[3] The quoted text is cited and translated into English from the not yet published dissertation of Fr. Alexandr Burgos, which is hopefully soon to be accessible for reading.

[4] According to another source, Elena. See in Оболевич Т., Аляев Г.Е. «Истина во вселенскости»: переписка С. Л. Франка с о. Климентом Лялиным (1937–1948). Вестник ПСТГУ. Серия I: Богословие. Философия.Религиоведение. 2021. Вып. 93. С. 93–130, p.122.

[5] Idem.

[6] See footnote 3.

[7] See selected quoted on the issue from Н.О.Лосский. История русской философии at “Руниверс Логосфера” project website, URL: https://runivers.ru/philosophy/chronograph/450690/

[8] Предисловие кн. Е. Н. Трубецкого к изд. «Владимир Святой и христианское государство». — М.: Путь, 1913. — С. 6, 7, 47. URL: https://viewer.rsl.ru/ru/rsl01003809852?page=10&rotate=0&theme=black

[9] Solovyov V. ‘Russia and the Universal Church,’ an English translation published in 1946, pp. 34-35, URL: https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.169645/page/n37/mode/2up

[10] «Русское слово», № 192, 21 августа 1910 г. cited and translated from “Руниверс Логосфера” project website, URL: https://runivers.ru/philosophy/chronograph/450690/

[11] Оболевич Т., Аляев Г.Е. «Истина во вселенскости»: переписка С. Л. Франка с о. Климентом Лялиным (1937–1948). Вестник ПСТГУ. Серия I: Богословие. Философия.Религиоведение. 2021. Вып. 93. С. 93–130, p.123.

[12] See here in Church Slavonic written with modern Russian letters: https://azbyka.ru/chin-prisoedineniya-rimo-katolikov

[13] The critics refer to Соловьев В., «Из вопросов культуры», 1893

[14] Pan-slavic and ethno-superiorist nationalists among the Russian intelligentsia, to put it in a nutshell.

[15] Лопатин Л.М., Памяти Вл. С. Соловьева // Вопросы философии и психологии. Кн. 195, 1910. URL: https://www.vehi.net/soloviev/lopatin.html#_ftn1

[16]‘29 Q: But if a man through no fault of his own is outside the Church, can he be saved?

A: If he is outside the Church through no fault of his, that is, if he is in good faith, and if he has received Baptism, or at least has the implicit desire of Baptism; and if, moreover, he sincerely seeks the truth and does God’s will as best he can such a man is indeed separated from the body of the Church, but is united to the soul of the Church and consequently is on the way of salvation.’ URL: https://jimmyakin.com/the-catechism-of-st-pius-x-4

[17] Ельцова К., ‘Сны нездешние (к 25-летию кончины В. С. Соловьева). Современные записки’. Кн. 28, 1926. Cited from Мочульский К.В., Владимир Соловьев. Жизнь и учение, полемизируя с Розановым, URL: http://www.vehi.net/mochulsky/soloviev/14.html#_ftn5

[18] Колосов Н., ‘Об исповедании В. С. Соловьева’ URL: http://www.vehi.net/soloviev/kolosov.html