Part 1 of a 3-part Series. You may read the other parts here: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

In his First Epistle to Saint Timothy, Saint Paul says that he is not sure when he can come to visit Timothy, but meanwhile he is giving him instructions “so that … you may know how one ought to behave in the household of God, which is the Church of the living God, the pillar and bulwark of the truth” (1 Tim 3:15).

This statement raises a question for us, too: How ought we to behave—or, as other translations have it, “conduct ourselves”—in the church? More particularly, since the liturgy is the very expression and summation of the Church’s life, how ought we to behave when we enter into a church and step into the sacred domain of the liturgy that takes place within its walls? The liturgy, with all its complex dimensions—vertical and horizontal, transcendent and immanent, literal and symbolic, visible and invisible, heavenly and earthly—is a microcosm of the whole of Catholic life. As a result, how we worship at Mass is an expression of our entire life of faith. This is why the way in which the Holy Mass is celebrated not only expresses the faith but also shapes it and transmits it. If the celebration is somehow not as it should be according to the judgment of the Church, the result over time will be a malformed and eventually falsified faith in the people.

Pope Benedict XVI once spoke of the need to “intensify the celebration of the faith in the liturgy, especially in the Eucharist.”[1] It seems that sometimes Catholics feel that simply showing up for Mass, preferably on time, is participation enough; why should we, or how could we, intensify that participation? One of the most important aspects of our participation, and the one that I will concentrate on in this series of articles, is our singing at High Mass and our attentive listening to the chants of the liturgy.

The Centrality of the Liturgy

First, the groundwork. The Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium of the Second Vatican Council states that the liturgy “is the primary and indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive the true Christian spirit.”[2] Again:

The liturgy, “through which the work of our redemption is accomplished,” most of all in the divine sacrifice of the Eucharist, is the outstanding means whereby the faithful may express in their lives, and manifest to others, the mystery of Christ and the real nature of the true Church.

Because the liturgy is “an exercise of the priestly office of Jesus Christ” and

the whole public worship is performed by the Mystical Body of Jesus Christ, that is, by the Head and His members … it follows that every liturgical celebration, because it is an action of Christ the priest and of His Body which is the Church, is a sacred action surpassing all others; no other action of the Church can equal its efficacy by the same title and to the same degree.

And the Constitution does not hesitate to draw this conclusion:

The liturgy is the summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed; at the same time it is the font from which all her power flows. … From the liturgy, therefore, and especially from the Eucharist, as from a font, grace is poured forth upon us; and [by it] the sanctification of men in Christ and the glorification of God, to which all other activities of the Church are directed as toward their end, is achieved in the most efficacious possible way.

We need to read that description again and again, and ask ourselves if this is our own understanding of the importance of the sacred liturgy in our lives as Catholics. I have often been surprised at how frequently even men and women of orthodox faith and irreproachable morals are unaware of the profound centrality, the all-encompassing governing role, the Church’s liturgy should have in their own personal and family lives. They are living under the influence of a Protestant, individualist mentality that has to be gently but firmly put aside, not just in one’s thoughts, but in the structuring of one’s daily life.

The High or Solemn Mass and the Low Mass

Having seen its centrality and ultimacy in the Christian life, we now need to ask ourselves how the liturgy is to be celebrated, and what our role in it should be.

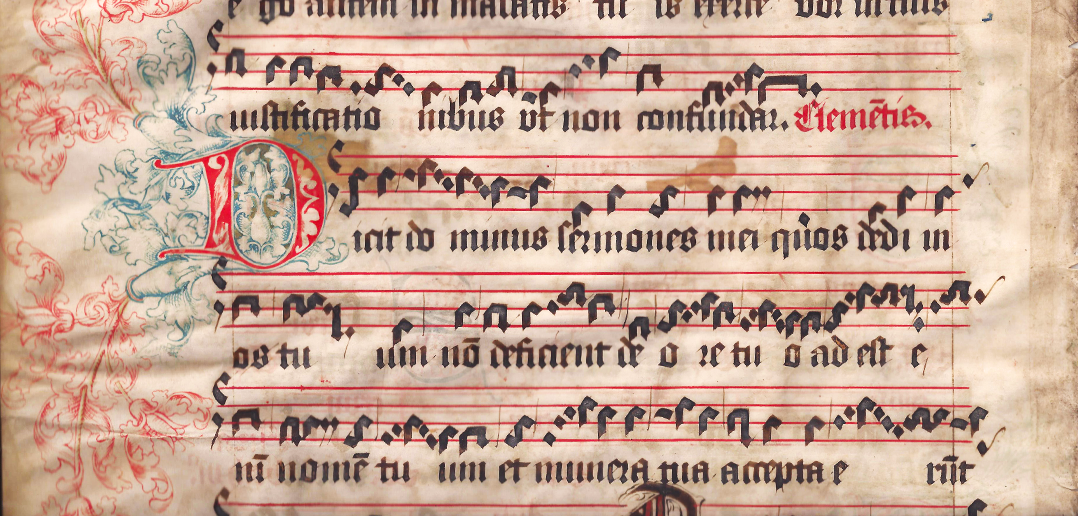

Ancient Hebrew worship involved both singing and speaking; so did early Christian worship. By the time of the Middle Ages, the custom of the private “Low Mass” (called low because it was merely recited) had developed, in order to favor the celebration of a daily Mass by each and every priest, particularly ordained monks in monasteries.[3] The main Mass of the day, however, was always sung in full—a practice that remains alive to this day in traditional monasteries. The Catholic ideal of public worship, especially for Sundays and Solemnities, is the sung High Mass, the Missa sollemnis or Missa cantata.[4] The Liturgical Movement, a revival in liturgical spirituality in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, promoted the ideal of the solemn sung Mass, as do the magisterial and papal documents of the past one hundred years.

So, then, not only should the singing of chant be frequent in our churches, but you, when you attend that High Mass, should be singing the chants that pertain to the faithful! This chanting together is the most significant external aspect of “active participation” rightly understood; it is one of the most precious exterior signs of our unity as members of Christ’s Body. Obviously, there is an internal aspect, too, namely, that we be attentive to the meaning of what we say and do, and really mean it and internalize it through meditation. But these internal operations are greatly enhanced over time by the external actions. There is no opposition or contradiction between external and internal, except where the internal participation, which is more fundamental, is attacked or undermined in the name of an exaggerated external activism, where people are “kept busy” talking or being talked at, and leave the church without ever having once genuinely prayed.

It is important to point out, lest there be any misunderstanding, that Divine Providence allowed the Low Mass to develop for the immense benefit of the clergy and the faithful, since it fosters a profound spirituality of meditative silence and, practically speaking, allows for the daily celebration of Mass in such a way that clergy can offer the Holy Sacrifice with regularity and the laity can participate in the midst of a busy schedule. My lavish praises of the sung Mass do not cancel out the devotional role of the Low Mass, but rather, balance a healthy love of this simpler form of celebration with the rightful place of honor that belongs to the magnificent fullness of our public worship when executed with all the ritual and music that befits it by tradition.

Singing the Mass

What are some of the advantages to the Sung or High Mass? For one thing, since this form of the Mass has a fuller ceremonial, with more roles and more music, it permits a fuller participation of all the people— celebrants, assisting ministers, choir or schola, and congregation alike. Famously, the Second Vatican Council promoted “active participation,” but we shall see that the Council had in view several lofty aims, many cuts above the low aims and aimlessness of today’s parochial mediocrity.

Mother Church earnestly desires that all the faithful should be led to that full, conscious, and active participation in liturgical celebrations which is demanded by the very nature of the liturgy. Such participation by the Christian people as “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a redeemed people (1 Pet. 2:9; cf. 2:4-5), is their right and duty by reason of their baptism.

How will this right and duty be exercised? Among other things, the Second Vatican Council declares that “steps should be taken so that the faithful may … be able to say or to sing together in Latin those parts of the Ordinary of the Mass which pertain to them” (SC 54), and that “the Church acknowledges Gregorian chant as specially suited to the Roman liturgy; therefore, other things being equal [ceteris paribus], it should be given pride of place in liturgical services” (SC 116).[5]

How often have you been to a Novus Ordo Mass that respected and implemented these clear words from Vatican II? Ironically, complete fidelity to Vatican II on this and so many other points will be found today only in the chapels, parishes, and schools where the traditional Latin Mass is being celebrated! Wherever the teaching of the Council is being followed, we will find a common practice of singing the Ordinary of the Mass, that is, the prayers that don’t change from day to day—the fixed prayers of the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Agnus Dei; the responses like “Et cum spiritu tuo,” “Amen,” “Deo gratias,” and “Sed libera nos a malo.” These prayers that everyone sings together are some of the most important in the entire liturgy. And we sing them in Latin (or, for the Kyrie, in Greek). We are fulfilling the Council’s request. In such communities, one also finds the regular chanting of the Propers, the most beautiful melodies ever composed in human history.

The same Council said: “the use of the Latin language is to be preserved in the Latin rites” (SC 36.1). Latin’s prerogatives were enunciated more than once at this Council, whose speeches and liturgies were conducted almost entirely in Latin. (One more reason not to convene Vatican III until the Church on earth can get its act together.)

In short, Vatican II is telling us that if the Mass is to be chanted, then everyone should participate in singing the Ordinary of the Mass—not exclusively a trained choir. Now, skeptics among my readers might well be wondering if Vatican II’s directive can be trusted; after all, a lot of wonky things are said to have come out of that Council. Couldn’t this be just one more loony idea? The answer is as forceful as it is simple: in this matter, Vatican II was merely repeating what Saint Pius X, Pius XI, and Venerable Pius XII had already been teaching throughout the twentieth century. And these Popes said it far more strongly than the Council did. But I will leave that for the next article.

NOTES

[1] Apostolic Letter Porta Fidei.

[2] By the term ‘liturgy’, although we are referring primarily to the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, we are also including the celebration of the other sacraments and the Liturgy of the Hours or Divine Office.

[3] For more, see my chapter, “The Loss of Graces: Private Masses and Concelebration,” in Resurgent in the Midst of Crisis: Sacred Liturgy, the Traditional Latin Mass, and Renewal in the Church (Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2014).

[4] I am aware of the distinction between a solemn Mass and a sung Mass, but this distinction is not pertinent to the main argument of this article.

[5] It is always necessary to point out to people that this “other things being equal” phrase strengthens the primacy of chant in this article, rather than weakening it. A paraphrase would be: “Gregorian chant, even if other things are equal, still deserves the first place in the liturgy, because it is the chant specially suited to the Roman liturgy.”