Above: 1965, Queen Elizabeth II sits in a carriage during the Opening of Parliament, Queens royal procession.

My silence is no proof of malice, as his Majesty can well know by many other tokens, nor is it shown to be any disapproval of your law. Indeed it should be taken rather as a mark of approval than of disapproval, in accordance with the common legal rule [Qui tacet consentit] ‘he who is silent seems to consent.’

– St Thomas More[1]

Since Monday, a great silence lay across the Realm. On the afternoon of the 19th of September, the late-Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of the other fourteen Commonwealth Realms, was laid to rest in St George’s chapel in Windsor after a magnificently solemn Anglican state funeral. Two minutes of silence were observed at 11:55am during the funeral service at Westminster Abbey and this silence seemed to punctuate the incessant noise of the modern world as both her former subjects, and people from around the world, commemorated the public centre of the life of the gens Anglorum, gens Pictorum and gens Scottorum, as well as the peoples of her other realms. In an age where nearly everything is disposable the Queen seemed solid, dependable and reassuringly unchanging. Her funeral captured this spirit and the world has rightly been captivated by the splendour and dignity of the British pomp on display during this period of National Mourning and the Accession of King Charles III.

In February of this year Elizabeth II had become the first British Monarch to reach their Platinum Jubilee, after 70 years of service. Celebrations to mark this extraordinary and historic anniversary culminated in the Platinum Jubilee Central Weekend in June. During this special bank holiday weekend, the country enjoyed countless street parties – altogether wholesome affairs that displaced the omnipresent rainbow flags of ‘pride month’ with Union Jacks – as well as pageants and parades showcasing the marvellous spectacle and ceremony (inherited from her medieval Catholic past) that Great Britain is rightly renowned for preserving.

Uniquely for contemporary political figures, praise for the Queen was nearly completely universal. Her death, on the Feast of Our Lady’s birthday, has precipitated an outpouring of effusive praise and eulogy, including from most British and Commonwealth Catholics. During her seventy-year reign Queen Elizabeth’s personal conduct was seemingly beyond reproach. In a world of increasingly vulgar and unsavoury public figures the Queen has embodied a regally stoic, quiet duty that seemed to reach to us from another age. The public enthusiasm for the Queen’s milestone, and the mourning at her passing is also clear evidence that, deep down, people have great affection for the medieval forms of public life, and are rather anxious to protect those few that remain.

Lodged within the public grief are further emotions still. The mourning was not only for the Queen. For Britons, she was the last living link with ‘the before time,’ with the age of world-leading British culture, industry and engineering, with the ‘national myth’ of the “Finest Hour” during the Second World War victory – which is so central to our old civil religion – and with the colossal Empire that once spanned the globe. The young Elizabeth received the news that her father King George VI had died, and that she was the new Queen, while conducting a royal tour of Kenya, just one of many British colonies at that time. On her return to London Airport, she was met by her first Prime Minister – Winston Churchill.

All of these national memories have resurfaced following her death and the country is undergoing a period of reflection on the course of her reign, and the state of the nation compared to 1952. I fear that the ramifications of this inevitable soul-searching will, almost certainly, be bad. In losing such an implacable and seemingly permanent sovereign and mother of the nation, I fear, there will be a general sense of unmooring from past ‘certainties.’ In this atmosphere the surviving medieval forms in the British Constitution may come under grave threat.

Queen Elizabeth II was not the katechon of 2 Thessalonians but I fear that she was (like Benedict XVI) a ‘katechonic figure.’ It is very possible that, as we enter the new ‘Carolean age,’ the country will formally complete what she has already undergone in spirit and become officially secular. If this happens, then it will finally conclude the long process of formal national apostasy from Christianity that was set in motion by Henry VIII with his break from Rome. Merry England will have completed its journey from discipled nation of Christ to a “grey and gay” apostate nation, whose public religion is the same as every other post-Christian country: materialist idolatry.

Amidst the chorus of praise for Her Majesty in the last few days I must register a quiet, regretful dissent from this unqualified acclaim. I am a monarchist and regard Monarchy as supremely fitting for a political community, reflecting as it does, the monarchy of the family below it, and, ultimately, the Monarchy of Heaven above it. Monarchy is an embodiment of Edmund Burke’s ‘communion of the living, the dead, and the unborn,’ that constitutes a well-ordered society. Although this intergenerational covenant has been repeatedly violated to the point of near destruction, the contemporary House of Windsor is still a potent symbol of national continuity, and a living link to England’s Catholic foundations.

The Crown is a kind of ‘sacred canopy’, where the monarch is head of society, rather than just head of that limited aspect of society we call ‘the State.’[2] The monarch is bound to the people in a fiduciary relationship, where, following Christ’s model of servant leadership, they are obligated to defend their subjects. The Good Shepherd lays down His life for His sheep. Along with the funereal and contemplative silence that has rested across the Realm there was another kind of silence that hovered over Elizabeth II’s reign. That was, of course, the lifelong, purposeful silence[3] of the late Queen herself who made this silence her watchword and guiding policy. Never complain, never explain. It is striking that, given this leitmotif, with all the hours of media coverage and inches of column analysis that the late-Queen’s death has occasioned there is a rather apparent and soon-reached limit of things to say about the Queen herself. Evidently, the Queen considered pragmatic silence to be the supreme means to fulfil her duty and pass on what she had received.

Catholic responses to the Queen’s death have tended to cluster around two opposite poles. Some, among the first, overwhelmingly British pole have eulogised the Queen as a “defender of the faith,” “the greatest Christian of our lifetime” and other tendentious excesses. Meanwhile, many American traditional Catholics have shown an almost revolutionary antipathy towards monarchy qua monarchy and rushed to blame the late-Queen for nearly every anti-Christian ill that has ailed Britain and the Commonwealth Realms over the course of her reign. There has been some lively debate about the choice of many Catholic churches in the United Kingdom to organise Requiem Masses for the late-Queen and for the Cardinal-Archbishop of Westminster Vincent Nichols to even “assist at a Protestant Service” by reading a prayer at the Queen’s funeral. In the meantime, a middle ground evaluation of the late-Queen and her reign seems to have been lost.

I hope that my moderate criticism and perplexity can stand in the tradition of the medieval filial petition. Since the King was the ‘father of the fathers of the realm,’ a good medieval King exercised his authority and power in a paternal manner. He was the supreme magistrate (hence why his house was a court) and therefore the fount of justice. He accepted complaints, requests, and petitions from people of all social stations who sought his grace and remedy when there was some injustice that was injuring them. It is in this manner, and not a republican revolutionary one of attacking the institution itself, that I present my petition regarding the late Queen Elizabeth.

The Slow Apostasy

In her public statement following the death of the Queen, Britain’s new Prime Minister Liz Truss called the Queen “the rock on which modern Britain was built.” In a certain sense this is an accurate characterisation. As a result of her public policy of silence the late-Queen was a kind of palimpsest – onto which could be projected the values, opinions and tastes of whoever chose to do so. Did silence as a public policy amount to giving tacit consent to all the policies of her elected governments?

When it can, the Revolution against Christian Civilisation likes to clothe itself in the remaining legitimate forms of the Christian social order. Modern history testifies that a slow speed, ‘Fabian strategy’ for the Revolution has been more effective than a fast speed radical upheaval, which nonetheless favours the decline towards the same point of arrival. Consider the historical success of Anglicanism itself in steadily draining the Christian substance of the English people as opposed to the radical ‘left wing’ of the Protestant Revolution, such as the Anabaptists of Münster, whose radicalism alarmed contemporary public opinion and provoked a violent reaction. Witness the success of LGBT activists in securing widespread public approval of homosexuality through campaigning for gay ‘marriage,’ rather than advocating for the complete abolition of marriage; an unnatural fiction widely ‘sold’ to the public as a way of domesticating and normalising a ‘problematic’ minority.

It is quite clear that, once time has passed, emotions have cooled, and future historians are able to study the ‘New Elizabethan Age’ dispassionately, the only conclusion they will be able to reach, is that Queen Elizabeth II’s reign was nearly a completely unmitigated decline for the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth Realms. By nearly every measure, be it political, cultural, economic, social, or diplomatic, the achievements and self-confidence of the United Kingdom have diminished dramatically in those seventy years.

Yet all these woeful developments pale in comparison to their shared remote and fundamental cause; the big story of Elizabeth’s Reign, which has been the near-total evaporation of the last vestiges of Christianity in the Realm. In 1952 most people still had enough residual Christian sensibility to recognise at least most of the natural law. For example, in 1955, Queen Elizabeth’s younger sister, Princess Margaret, was pressured into declining marriage to the divorced Peter Townsend being “mindful of the Church’s teachings that Christian marriage is indissoluble,” and the public scandal that would result. Now at the nightfall of the Queen’s reign nearly all such beliefs, customs, and sensibilities lie in ruins. In 1992 the Queen attended the second “marriage” of her daughter Anne, the Princess Royal, in a Church of Scotland ceremony (where divorce and remarriage was permitted). In 2005 the Queen did not attend the civil wedding of her firstborn son and heir Prince Charles to his long-term mistress but did attend the Anglican “Service of Prayer and Dedication” that followed.

This rapid Christian diminution has been both expressed and effected by the culture of death that has steadily achieved statutory establishment, with the legalisation of abortion, homosexuality, no-fault divorce, pornography, mandatory sex education, same-sex “marriage” and every other horror that has assailed the remains of Christian Civilisation.

Under the British Constitution none of these laws could have been passed without the granting of Royal Assent; the final stage of the legislative process. Even if the Queen personally disapproved of any of these pieces of legislation, they nevertheless would not become law unless, as the Queen’s emissary pronounced in Parliament, La Reyne le veult (“the Queen wills it”). As part of her supposedly ‘apolitical’ exercise of office the Queen never refused to grant this Royal Assent, knowing that had she done so it would have precipitated a constitutional crisis and threatened the very position of the monarchy.

Dr Alan Fimister has remarked that in conserving some of the empty appearances of true religion, Anglicanism fulfils the role of assuaging the subconscious guilt of the English as they steadily apostatise from Christianity. The Queen was sometimes described as the last believing Anglican, and while we do not know too much about the late-Queen’s personal religious beliefs there were some clues.

Many commentators have noted, and speculated, about why the Queen suddenly started speaking much more about her personal Christian faith, from her Christmas broadcast to the nation in 2000 onwards. Explanations for these more overt Christian messages vary; some saw the hand of George Carey, then “Archbishop” of Canterbury, others speculated about the encouragement of Prince Philip and members of the public, while others detected the influence of the death of her mother, which may have encouraged the Queen to express herself more freely. However, could the reason for the increasing prominence of Christian themes in these annual public broadcasts have been her growing realisation, even guilt, that she has reigned over a period of the greatest diminishment of Christianity, and public morals, in her realm in hundreds of years, and that this will be her greatest historical legacy?

The Royal Assent

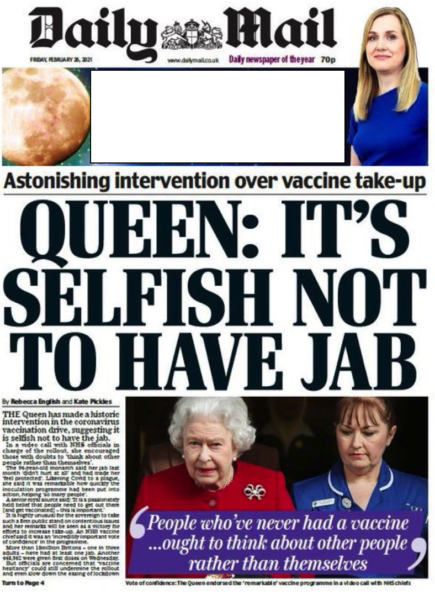

It is an oft-repeated inaccuracy to claim that the Queen is ‘apolitical.’ Of course, such a notion of public ‘apoliticism,’ is, like liberal “neutrality,” in concrete terms, a phantasma in itself. As the 1992 Catechism states: “Every institution is inspired, at least implicitly, by a vision of man and his destiny, from which it derives the point of reference for its judgment, its hierarchy of values, its line of conduct.” In fact, the Queen has made a number of subtle but overt political interventions during the course of her reign, even over controversial political issues like “diversity and inclusion” (read destabilising mass immigration), anti-Covid “fashionable injections” and “anthropogenic climate change.” What almost all of these political signals have in common is that they were simply a re-expression of her government’s policy at the time, or at least the objectives of the oligarchic powers that stand behind the elected officials of her government.

As described by Mr Jamie Bogle, under the current constitutional dispensation, the process of Royal Assent is largely a ceremonial ritual where the Queen gives general assent to several Parliamentary Bills at one time. The authoritative constitutional theorist, and author of Parliamentary Practice, Erskine May confirmed that the monarch’s sanction “cannot be legally withheld.” Royal Assent was last refused by Queen Anne in 1708, in relation to a Scottish militia Bill, and constitutional convention dictates that the Monarch cannot refuse assent, unless in an emergency, without arrogating powers that do not belong to them, and thus fundamentally damage the Constitution itself. Alas, such is the revolutionary settlement and “crowned republic,” that has obtained in Great Britain since the 1688 Inglorious Revolution ousted the last Catholic monarch.

Accordingly, the reserve power to refuse assent is, according to “Dicey’s exception,” only permitted to be used when the Constitution itself is under threat, as defined by Parliament and the courts. As St Paul tell us: “the powers that be are ordained of God” (Romans 13:1). Attempting to seize or usurp power is therefore an evil. Moreover, the passage of enough time has the effect of legitimising a usurping power, since legitimacy is itself not an end, but a means to the end of good government. An historical example of this dynamic was in the Papacy’s recognition of the Protestant Hanoverian settlement in Britain in 1766 once the possibility of a Jacobite counter-revolution looked nearly impossible.

However, might the Queen have appealed to a higher law than the British Constitution – namely the Natural Law and Divine Positive Law on which that Constitution, was originally based? When the Queen made her Coronation Oath on the 2nd June 1953, she became bound to an oath before Almighty God which rooted her authority in “the maintenance of the Laws of God… [and] the Protestant Reformed Religion”:

Archbishop: Will you to your power cause Law and Justice, in Mercy, to be executed in all your judgements?

Queen: I will.

Archbishop: Will you to the utmost of your power maintain the Laws of God and the true profession of the Gospel? Will you to the utmost of your power maintain in the United Kingdom the Protestant Reformed Religion established by law? Will you maintain and preserve inviolably the settlement of the Church of England, and the doctrine, worship, discipline, and government thereof, as by law established in England? And will you preserve unto the Bishops and Clergy of England, and to the Churches there committed to their charge, all such rights and privileges, as by law do or shall appertain to them or any of them?

Queen: All this I promise to do.

Despite much public agonising and waffling, the current position of the Church of England is that marriage is between a man and a woman and “combines strong opposition to abortion with a recognition that there can be – strictly limited – conditions under which it may be morally preferable to any available alternative.”[4] Granting Royal Assent to both legalised abortion and same-sex “marriage,” would have presented the Queen with a dilemma as these articles seem to have clashed with her Coronation Oath. Under the British Constitution, did fidelity to her oath constitute grounds for the use of “Dicey’s exception” and the refusal of Royal Assent?

To the aforementioned argument that the Queen has been in an impossible constitutional bind – caught between her personal religious commitments, her position as Governor of the Church of England, and her constitutional role as a politically-impartial ‘referee’ – we can perhaps consider other European monarchs who faced similar dilemmas but chose different paths. Most famously, King Baudouin of Belgium was confronted with a bill legalising abortion in 1990 and refused to give his Royal Assent. With the agreement of the King the government suspended Baudouin as head of state for a day while they enacted the law. The Federal Parliament then reinstated the King the next day. While some have described Baudouin’s actions as an empty gesture I would aver that they did at least signal to the Belgian people that the sovereign disapproved of this grave and immoral attack on life.

Could the Queen have at least made such a public testimony against the parliamentary attack on the Natural Law and maintained her throne? Certainly, public respect for the Queen would have made it very difficult for the government to abolish the monarchy over such a principled stand. More likely, a comparable legal solution to that of Belgium in 1990 would have been found and the Queen would have had to surrender the remaining royal prerogatives that she had. Yet it seems that abortion, to take the most egregious example, was a sufficiently worthy cause for which to consider making such a sacrifice.

Had the Queen signalled her Christian opposition to the return of child sacrifice then the consciences of the British people may have been stirred and she might have conducted a great Christian witness. It has been said that when Rome sneezes Canterbury catches a cold. In this dismal age we are in desperate need of radical and heroic Christianity. When most of the Catholic hierarchy failed to act against the return of child sacrifice to the West, when abortion was legalised, the testimony of Christianity to the world was dramatically vitiated and has been ever since. The world needs reminding that the Gospel is something that Catholics will die for.

Politicians: Figureheads of the Oligarchs

There is another argument that, by withholding Royal Assent, the Queen could have initiated a just rebellion against a tyrannical government. The Angelic Doctor writes:

A tyrannical government is not just, because it is directed, not to the common good, but to the private good of the ruler, as the Philosopher states (Polit. iii, 5; Ethic. viii, 10). Consequently there is no sedition in disturbing a government of this kind, unless indeed the tyrant’s rule be disturbed so inordinately, that his subjects suffer greater harm from the consequent disturbance than from the tyrant’s government. Indeed it is the tyrant rather that is guilty of sedition, since he encourages discord and sedition among his subjects, that he may lord over them more securely; for this is tyranny, being conducive to the private good of the ruler, and to the injury of the multitude (II-II q42 a2 ad3).

This argument clearly hinges on the question of whether the parliamentary government of the United Kingdom was a tyranny at the time it legislated the articles of the culture of death. It might be argued that ‘parliamentary democracy’ has long been de facto abolished, if not de jure. The Covid tyranny of the last two years was something of a revelation that our political public leaders seem to be subordinated to global private interests. These legislators driving through “UN 2030 agenda” policies such as ‘Net Zero,’ “reproductive rights” and mandatory injections seem to act more as coordinated ‘policy distributors’ rather than ‘policy makers.’ There is suggestive, but growing evidence of the sexual and financial blackmail that may be used to effect this control of legislators and maintain the illusion of ‘democracy’ (for example the Epstein scandal). In Boris Johnson’s eulogy he described the Queen as a model “figurehead” and it might be the case that this is exactly what the elected parliamentarians are as well! Nevertheless, it is beyond the scope of this essay to reach a conclusion on this question.

Hypothetically might the Queen, as legitimate sovereign, have legitimately determined the legislators of the House of Commons as tyrannical rulers, seeking the private good of oligarchic interests, and discerned that her subjects would suffer greater harm from the tyrants’ government than the disorder of a constitutional crisis provoked by the withholding of her royal assent? Perhaps such thoughts passed through Elizabeth’s mind in the silence of her reign. It is also possible that the Queen supported the legislation contrary to the Natural Law, certainly it seems that her late-husband was an adherent of Malthusianism and population control.

It seems likely that these kinds of constitutional and moral debates will multiply as the distance between our own time and the Second Elizabethan age lengthens and the catastrophic retreat from grace deepens. We are also likely to discover more about the events and conversations that took place during the great silence. It may well be that Elizabeth II preserved us from even worse horrors during her seventy-year reign. Perhaps her restraining influence was more acute than we have so far conceived.

On every British coin famously appear the letters “F.D.”, standing for the title of the British monarch; Fidei Defensor, awarded to King Henry VIII by Pope Leo X in gratitude for his treatise against the errors of Martin Luther, “Defence of the Seven Sacraments,” possibly co-authored with St. Thomas More. What is less well known is that, in response to Henry’s polemic, Luther gave Henry the supposedly insulting title of ‘Rex Thomisticus,” Thomistic King. Not only was he referring to Henry’s scholastic sacramental theology but also to the ‘Thomistic mixed regime’ of the English Constitution. The Kingdom of England was governed by Dominium Politicum et Regale (Public and Royal Lordship), where everyone, including the King, was under the rule of law. As this rule of law has been eroded by powerful elites men have come to yearn for past establishments. We are liable to grieve a momentous passing such as that of Elizabeth II since, in the process of the dissolution of Christendom, each revolutionary settlement is less Catholic than the settlement that preceded it. As we mourn the late-Queen, who possessed many natural virtues, let our considerations be governed by reason rather than simply emotion. It would have been necessary for the Queen to have the clarity of the doctrine of the Angelic Doctor in order to defend her subjects and yet where were the Catholic bishops to offer it? Silence. The trouble with emphasising the virtues of the ‘settled constitution’ too much is that this can elide with sentimental notions about the former-Queen, as well as the inherent desire for comfort and security, that we all have in this all too comfortable age, and thus the imperative to ‘transform all things in Christ’ can be lost. Let us be vigilant; not forgetting that we Catholics must never stop working for a full conversion of the political order and be mindful of the temptation towards silence where it ought not to be.

I die the King’s good servant, and God’s first.

– St Thomas More

Regina Elizabeth II Requiescat in pace

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

[1] T. Stapleton, The Life and Illustrious Martyrdom of Sir Thomas More (Dallas: CTMS Publishers at the University of Dallas, 2020), 97.

[2] A. Nichols, The Realm: An Unfashionable Essay on the Conversion of England (Oxford: Family Publications, 2008), 44.

[3] See ‘Apostolic Majesty’s’ examination here.

[4] “Church of England bishops say that over 98% of UK abortions are ‘morally wrong.’” Premier Christian News (2020, February 11).