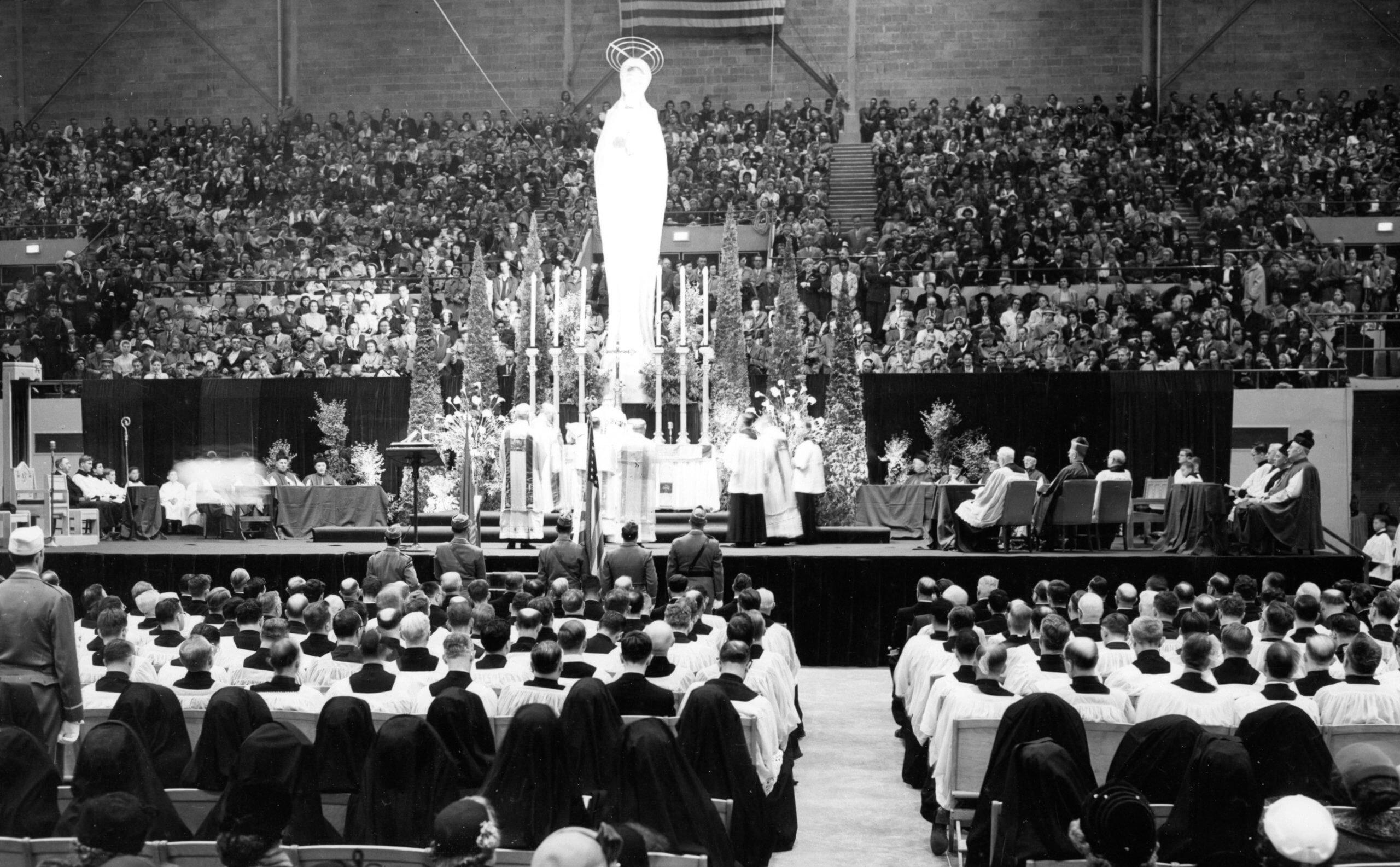

Above: the first evening Mass in the diocese of Milwaukee consecrates the diocese to the Immaculate Heart of Mary in 1954. Photo credit.

A very interesting and provocative reprint, the first volume of Integrity will be welcomed by all those desiring to delve deeply into such topics as: the history of the consciousness of the lay apostolate in the 20th century; the Catholic Action and Catholic Worker movements; and the theology and apologetics being promoted in the decades leading up to Vatican II.

Integrity was a Catholic magazine founded just after the Second World War. Arouca Press has obtained and begun to re-publish the entire ten-years-worth of issues in a multi-volume series. Aimed at Catholics who “are a little vague as to what constitutes a Christian lay life today,” its editors described it as a “lay magazine whose staff is Catholic” and strove to realize a “re-integration of religion and life in the modern world.” Published monthly between 1946 and 1956, it addressed “the problems of Catholic lay life: such problems as family life, psychiatry, women in contemporary society, education, the land movement, the movie, security and God’s providence, trends in medicine, inter-racial considerations, organic farming, work, and the radio.” Although it never had a large circulation in its own day, it represents a special historical record of Catholic thought in this era in the United States. Obviously an important source for understanding those times, it may prove helpful as we consider similar issues in our own times—or at least understand how we arrived at some of the attitudes we see in Catholicism today. So far three volumes of three issues each have been published by Arouca Press. Here I’ll take a look at the first volume.

I wish I could recommend Volume I (containing the first three issues of the magazine) as containing more answers than questions, but I don’t think I can. On the one hand, some aspects are so dated that they lose all helpfulness except for the historian; on the other hand, an activism which smells unbalanced (to me, at least) permeates many of the articles. Let’s look at a few examples.

I found in the first issue of Integrity, at least, that any practical advice in it is largely undermined by how much the world has changed for the worse since it was published. In its pages there is still the sense that the trend of modernity can be arrested before it gets worse. Eighty years later, with the downward rush exponentially increased, the idea that a sufficient number of workers espousing Catholic Action principles for evangelization could really change the face of American capitalism no longer seems grounded. But it is interesting to see that they still thought it was possible then. It could be a helpful data point in tracking the perceived Catholicity of our nation, for example.

There are some essays, however, which are excellent and still relevant. Dominican father Herbert Thomas Schwartz’s essay on Our Lady is notable for linking psychoanalysis with man’s search for mercy. By seeking to abolish guilt, Freudian psychology offers a false mercy at odds with the true mercy engendered by devotion to Mary, the Dominican says. This has particular relevance in the reign of a Pontiff who espouses mercy while seemingly trying to abolish sin after sin.

Carol Jackson’s essay on “The Frustration of the Incarnation” starts in a promising vein with an emphasis on the tendency to a false dichotomy between natural and supernatural spheres of life. However, it disappoints in a vision of a “Catholicized” version of American Society where “Converted psychiatrists might form a special elite of flagellants, scourging themselves constantly for their sins, the while repenting their foolish talk about masochism.” Again, “Radio City choruses, clad in long and formless garments” could perform “penitential dances to the Attende Domine, with the entire audience bursting forth on quia peccavimus tibi.”

Even allowing for humor, these and similar passages don’t ring true for me. Somehow the proposal of “several hundred thousand women” declining “as an offering for peace, to look in any store window during Advent” no longer seems to have much to do with where our world is at. I can certainly imagine an excellent Advent fast from shopping on Amazon as a personal discipline. But would it have a visible effect on the war in Ukraine? Maybe these writers challenge our lack of Faith. Or perhaps their optimism is no longer tenable. Jackson also writes: “What if all pious societies of men refused for a year to look at any women’s legs? What would happen to the sale of nylons? Very much of this sort of thing and the whole economic system would be threatened.” Well, considering the extremely high contraceptive rates in the US (considerably over half of the women of reproductive age, regardless of which stats you look at), I don’t think any number of Catholic men are going to threaten any economic system by not looking at any woman’s legs.

A similar shift in world view is appreciable in Ed Willock’s essay on “The Cross and the Dollar”. When he concludes that “Nothing short of total revolution can restore our world to Christ” I wonder if it would be now more appropriate to say, “Nothing short of a nearly-total destruction of the world as we know it right now could bring any restoration to Christ.” But I know that is open for argument.

Paul Hanly Furfey’s article “Are You Ashamed of the Gospel?” is thought provoking on questions of how Catholics can (or cannot) collaborate and agree with Liberal politicians on supposedly “common ground.” However, the treatment was cursory, and left the feeling that it would be a good book club conversation starter as long as there were a couple of theologians and philosophers in the room who really knew what they were talking about.

The second issue in this volume delves into the Catholic Worker and Catholic Action movements, containing many provocative essays that are worth reading to inspire discussion if you find yourself searching for answers on such topics as Catholic homesteading, the lay apostolate, or the history of lay movements in the 40s and 50s. Paul McGuire and Dorothy Day’s articles were very helpful in inspiring the conclusion to my recent piece on “The Universal Call to Hobbitness.”

In Paul McGuire’s article “There is a Solution,” we see a burning zeal for holiness combined with hints of the ecclesial restlessness and dissatisfaction which would erupt in the 1960s: “We have much dead timber in methods of organization and habits of mind… the Church is a dynamic not a static institution… it cannot be frozen in set forms.” The main takeaway from his article, is, however, that change for the better must start with us.

Several articles detail the Catholic worker movement in Canada and other parts of the world: certainly some helpful summaries of the themes they emphasized and methods they employed. Fundamentally, Peter Michaels argues, one must “stay in the dough.” “From this follows the very firm conviction of Catholic Action adherents that it is not for the Church today to leave the rottenness of western society but to transform it. They are opposed to all of what they would call ‘escapist’ movements; all efforts at flight away from our sick brethren into a cleaner atmosphere.” He says that despite controversies on this point within Catholic Action, “everyone would agree” that “no Christian can in good conscience flee the problems of the day in order to save himself. If he goes away (to the land for instance), it must be for a purpose related to the salvation of his city brethren.”

I personally have serious issues with this idea that every course of action has to have some apologetic end, even if remotely. While in some sense every action has an apostolic side by the fact that everything we do will have an influence for good or ill on other people in the world, I would argue that there are plenty of actions and even courses of life for which the apostolic is in some way an accidental and non-essential aspect. I hope to take this theme up in a future article, putting this idea in dialogue with those of supposedly “escapist” thinkers like John Senior. For the moment, let’s just note that rather than leavening the “rottenness of society,” the fact is that the Church was so focused on the problems of western modernity that many of her members and clergy eventually succumbed to the “unclean atmosphere” in the decades that followed.

The third issue in volume one, a Christmas number, treats of the theme of “Christ with us.” After a slightly sappy short story, a Dominican essay on how the incarnation affects the natural and supernatural aspects of man, comes a clever piece entitled “Case 13,013.” It presents the correspondence between a certain “Nahum Priest” and the secretary of the “Jericho Family Welfare Society”, and retells the story of the Good Samaritan from the point of view of the righteous priest who passed by the man fallen among robbers but conscientiously notified the government agency responsible for taking care of such situations. Responsibility is passed from one agency to another and discussed at various board meetings.

An article of Ed Willock, co-editor of Integrity at the time, tries to give examples of how applying knowledge gained by the Faith to everyday practical and socio-political issues might help us “catch a tiny glimpse of that totality which is Christ.” He considers bread, the annual wage, Jews, and “the housing problem,” concluding

I have briefly discussed four problems apparently unrelated, yet the solution to each proceeds from a true evaluation of the mystery of God become Man. Our error has been to classify all this as a religious view, something distinct from the economic view, the historical view or the practical view. Unconsciously, we have disincarnated God from the affairs of man. We dare to imply that God’s ideas as to the disposition of His universe are of questionable practicality.

He points out that we then fall into the error of supposing that “the Faith is only operative in the sphere of morality [text reads mortality, but this is obviously incorrect in context].” Willock writes that

Christianity is not merely a way of avoiding sin; it is a way of living. The Church, who speaks of Christ, is not interested in practical matters as a side line to saving souls. Practical matters are the way that people save their souls.

This is an excellent point, and one which I think it is easy for people to lose focus on. In the context of traditionalism, it is easy for people striving to be holy to mistake “piety” with “sanctity,” and approach life as if the only way to sanctify it was to heavily salt it with “devotions.” Devotions (like salt) are wonderful in small amounts, and certainly can help with prayer and making a conscious place for God in our lives. But the more fundamental aspect is that life itself as an integrated whole is where we become the people God wants us to be, is where we live holiness. We are doing one thing—life—in a way which is attuned to God, changing the whole flavor of life to match reality (all of which is ultimately God oriented) rather than trying to overpower and hide the flavor of “natural” and ordinary life with piety and moral rectitude. This idea of a unified life is behind the title of Integrity.

In conclusion, I’ll end with a quote from the last article of the Christmas issue. “As time marches on faster each day,” writes Jules Keating,

we cannot tell what the future will bring. We do know that a lasting peace must be founded upon a spiritual basis. Leaders in Church and State, in the army and the navy, in journalism and commerce, have all told us this time and time again. The world is growing smaller day by day. The airplane and the radio, to mention but two factors, have drawn the nations of the earth much closer together, for better or for worse. The spiritual basis for unity and peace for Catholics is their common membership in the Mystical Body. But Christ is the Head of that Body and the Head must control the members. Through the Church year, Christ assumes this leadership… He speaks to us through the teaching of the Church, but He shows us through the liturgy. The former reaches only the intellect, the latter touches the heart.

As we stand at the beginning of 2023, just as in 1946, we cannot tell what the future will bring. Much more unites and divides the world of today than the radio and airplane. But one thing at least is constant; the spiritual basis for unity remains Christ; the traditional teaching of the Church ensures that we know His commands; and the traditional liturgy ensures that our hearts are nourished. Without these, our intellect is set adrift in a humanistic void of dust and our heart is chilled in a hedonistic desert of relativism. We know that preservation of liturgy and doctrine are an essential part of the key for obtaining true integrity in our lives and in the world around us. Let us learn how to pursue integrity from both the insights and errors of those who have gone before us—in this case, in the pages of Integrity.