Religion Department Academics of a certain sort love to scandalize undergraduates by telling them that Jesus is a marginal figure in Church history; the real founder of the religion, they whisper, was Paul. In fact, they persist, the religion should really be called Paulianity.

From the standpoint of Roman Catholicism, there is some truth to the claim.

The Mass as Roman Catholics celebrate it today received its form under Paul. Paul changed the formula of consecration during the Mass, as well as the rites of baptism, marriage, confession, extreme unction (anointing of the sick), and burial. He entirely restructured ordination, banishing the seven-step structure Holy Orders had once known. To the governing apparatus of the Church, Paul gave the definitive power structure it enjoys today. Very nearly every religious community in the Church altered its formation, daily life, habit, governance, bylaws, and prayer life in response to Paul’s demands for change. Church thinking changed as well, with wave after wave of innovative theological ideas ushered in by Paul. In almost every respect, Church life can be described dualistically: either Prepaulian or Postpaulian.

I speak, of course, of Paul VI, Giovanni Battista Montini, who died in 1978 after a remarkably consequential fifteen year pontificate – one of the four or five most consequential pontificates in the history of the Church. Despite this fact, and even despite Paul’s recent canonization, he remains remarkably understudied. Any other pontiff of comparable transformative power would have been called “the Great” long ago. But real deep engagement with Paul’s pontificate has suffered from multiple causes. For one thing, Paul’s extraordinarily unappealing public persona has smothered interest in him: scholars work from some form of passion, and the seemingly joyless (the Italians said Paolo sesto Paolo mesto, “Paul the Sixth Paul the Sad”) pope has not generated it. Paul was also the archetypal bureaucrat; the transformations of his pontificate came mostly via committee, and in response to the Second Vatican Council. They have been variously assigned to the pope, the members of the committees, the faithful themselves, or the Holy Spirit.

2023 marks sixty years since the beginning of Paul VI’s pontificate, and the time has come for sober judgement and assessment. The changes Paul VI decreed have come under increasing criticism, due largely to the fact that the Postpaulian Church has been so obviously diminished in the West. One key fact has clearly emerged: Paul’s implementation of the Second Vatican Council, which had decreed things like “no innovation should be undertaken unless the good of the Church genuinely and certainly requires it,” was not in accord with Conciliar decisions themselves.

Paul undertook a systematic program of innovation covering every detail of Church behavior, from how often a priest should kiss the altar during Mass to whether or not Carmelite nuns can live according to the rule of St. Teresa of Avila (Paul didn’t think they could, a decision which is still being contested). Paul’s changes to the liturgy, since they affect the daily life of the faithful so much, are the obvious ones: where the Council had decided to keep Latin, Paul jettisoned it; where the Council decreed keeping “the treasury of sacred music,” Paul consigned it to oblivion; where the Council had said nothing at all about building new altars, communion in the hand, or versus populum masses, they all became Catholic practice during Paul’s pontificate – in at least one instance, however, directly contrary to his wishes.

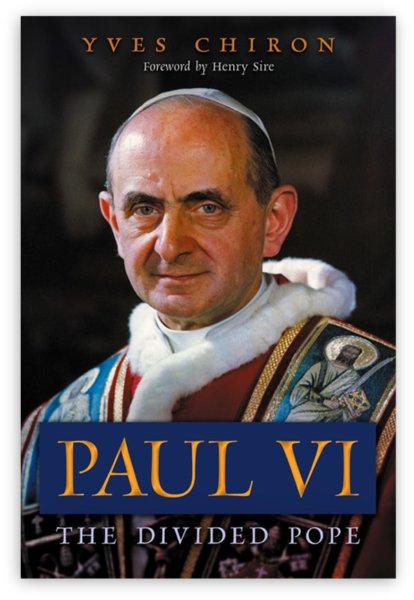

The best place to start with a serious engagement with the legacy of Paul VI is with Yves Chiron’s short biography, Paul VI: The Divided Pope (Angelico Press, translated from the French by James Walther, which a forward by Henry Sire).

Chiron, a Frenchman, has written voluminously on Catholic topics, from Benedict XV to Fatima to Padre Pio, always, it seems, on the general principle that there is value in a more disciplined, scholarly approach to the Catholic heritage of the twentieth century. He is known as a traditionalist, though this is evident more in his choice of material than in anything else; he does not write polemically. His biography of the Pontiff is worthwhile for three main reasons.

For one, it is really the only short, objective biography available in English; the best treatment of Paul’s pontificate, Peter Hebblethwaite’s, is three times as long and most assuredly a defense of Paul rather than pure biography; other short treatments are avowedly hagiographic or were written before his pontificate had concluded.

Secondly, Chiron has unusual depth in the French sources related to Paul’s pontificate, and it is undoubtedly French Catholicism which influenced Paul most (Jacques Maritain, Henri de Lubac, Jean Danielou, and others; when Paul came to the United Nations, he spoke in his fluent French). Wladimir d’Ormesson, a French diplomat in Rome, furnishes Chiron with useful official assessments of the young Montini. Chiron also personally interviewed Paul’s close friend, the philosopher Jean Guitton (who published Dialogues avec Paul VI during the pope’s lifetime), and he was able to use Guitton’s inside knowledge to structure much of his account of Paul’s life. Guitton’s ultimate assessment closes the book: “Paul VI did not have the makings of a pope. He did not have that which is characteristic of a pope: resolve, the strength of resolve.”

Thirdly, Chiron – who has also contributed a valuable biography of Annibale Bugnini, the Vatican official most responsible for the liturgical reform – understands the Vatican bureaucracy and how it works (that is to say, he understands it as well as anyone can, which is somewhat limited). What we need most is an understanding of how the decrees of the Second Vatican Council were turned into Church policy – a topic Chiron takes an interest in, and writes about. Take, for example, Chiron’s account of the generally unknown controversy about Latin in seminaries:

On January 25th, 1966, the Congregation for Seminaries and Universities published an instruction that Latin was to be retained in the seminaries for the celebration of Mass and for the recitation of the Breviary. Cardinal Lercaro, responsible for the liturgical reform then in progress, complained to the pope, as did several French bishops. Among them was Cardinal Villot, then archbishop of Lyon [the future Cardinal Secretary of State, and an extremely important prelate]. When he met with the pope the following February 22nd, he shared their concerns. He received a reassuring response, as a confidant testifies [Antoine Wenger, who write a biography of Villot]: “Paul VI could not disavow the Congregation for Seminaries and Universities. He said simply that the instruction was not imperative, but only indicative.” In the French seminaries, Latin was very soon to disappear from the liturgical offices.

Not imperative, but only indicative! And soon past tense. A very similar story appears in the memoirs of Archbishop Rembert Weakland, who as primate of the Benedictines led the resistance against the Conciliar decree, backed by Paul VI’s motu proprio Sacrificium Laudis, keeping Latin in monasteries. Chiron never mentions this, but he accurately describes the Vatican of this era as “a three-player game,” which the Pope, the Curial Committees and Congregations, and the Bishops and Abbots played against each other.

One of the easy conclusions that can be drawn from Chiron’s biography is that the Mass as celebrated today should truly be considered not the work of the Second Vatican Council but truly the work of Paul VI. It is postconciliar rather than conciliar. This confirms what Joseph Ratzinger said of the Novus Ordo Mass, “I can say this was not what the Council Fathers intended.” Chiron provides ample documentation of Paul’s interest in a vernacular liturgy, such as this from 1947:

Monsignor Montini expressed the opinion that one day the celebration of the whole “didactic part” (according to his expression) of the Mass in the language of the people should arrive. I remarked that it might well require a hundred years for that evolution. “No,” he replied, “an evolution that previously might have required a century can nowadays be realized in twenty years.”

He quotes the conclusion of Aime-Georges Martimort: “Nothing was decided, much less promulgated, without Paul VI being aware of it. He received the plans, which he annotated with his own hand, making his preferences clear and sometimes also his demands or refusals.” That the Mass is a papal rather than a conciliar creation does not make it any less valid for Catholics, of course; but it does make it clear that discussions of it should be separated from discussions of the Council. And whereas Paul permitted resistance from clerics of a modernizing tendency, even to his own decrees, Chiron is able to document his forceful crackdown on the use of older form of the Mass. He was capable of resolve against Tradition more than resolve against experimentation.

Chiron is interested in Paul’s legacy, and spends far less time evaluating him as a man. Paul’s strange romantic melancholy, his odd comparisons of himself to Hamlet, for instance, and Don Quixote; the tortured self-reflections he imposed on his audiences; the bizarre will he wrote (“I close my eyes upon this dolorous, dramatic, and magnificent world”) – Chiron has no room for such concerns, in a short biography of a man continually involved in important Vatican affairs from before Mussolini to the brink of the Reagan administration.

Similarly he spends no time on Paul’s deep and apparently sincere appreciation of many of the great saints, about whom he wrote convincingly and intelligently, or on the personal simplicity and humility which deeply affected many who worked for him and convinced them that he was truly a saint. Chiron’s omission of these details – and many others, for his was a busy pontificate, with change in every quarter of the Church, and controversies and dramas in nearly every one – points to the need for a complete, factual biography of Paul, as a means of understanding his immense shaping role on the Church of today. Many people have done important groundwork for such a biographical effort, Chiron foremost among them. The time is ripe.

In the meantime, we can use Chiron’s biography to draw further lessons. He focuses on what can justly be described as Paul’s career, legacy, and leadership. Much of this legacy is undoubtedly negative – Paul’s poor leadership undeniably ushered the Church into a state of crisis, a constant hemorrhaging of believers which shows no signs of letting up. In Paul we can see an ideological blindness to methods that are actually effective, a commitment to taking risks without any plan for assessing failure, and an organizational tendency to produce rules and then only selectively and rarely enforce them. We will take this up in our next essay, as a way of engaging with Paul VI on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of his accession. Picking up a copy of Chiron’s biography would be an excellent way to prepare for it: it is the least we can do to note the massive influence of St. Paul VI on the Church today.