Editor’s note: This is the first in a two-part series on the topic of cultivating a more authentic taste in music. The second part is available here.

There is an old saying that “one can find Catholic music performed everywhere except in Catholic Churches.” I was reminded of this tragically accurate quip when I was recently invited into a parish-wide conversation about liturgical music. To summarize this largely disheartening exchange: the pastor was clueless about what the Church actually taught about sacred music, letting himself be carried downstream by popular opinion. In turn most of the otherwise dedicated and orthodox Catholics involved in the “music ministry” (a tragic term if the Church ever had one) were convinced that rock music was not only liturgically acceptable, but a great good propagated by the Bishops. Even after an extended conversation about what Church documents on sacred music and liturgy actually ask for, the luminous character of her musical tradition, and the nature of beauty itself in indicating a preference of certain forms of expression over others, the rock and roll crowd held stubbornly to their “righteous” cause. Personal taste and popularity held the day, another parish remained aesthetically in the dark, and her members were denied the opportunity to begin to understand music as God would have us hear it.

Taste is a peculiar thing, and it can hold a powerful sway over our better judgment. It can lead us into a double-think scenario where our lower faculties lord over our intellect; this is not unlike an addiction. Taste in music may well be the most personal and formative of preferences, while science continues to study and confirm the narcotic-like power of our favorite tunes. This is why the discernment of music in relation to Catholic spirituality is so critical. And why we need to be asking heartfelt questions regarding music, morality, and the Catholic life.

While such discernment — let alone changing our musical preferences purposefully — can be very difficult, this problem is exponentially compounded by our society’s rejection of the right to question another person’s taste. Aesthetic self-reflection is also out, replaced by rather passive and knee-jerk processes such as changing or “evolving” tastes (in other words, most folks never progress beyond the listening habits of their teenaged years.) Yet never mind that such an uncritical attitude puts one completely outside of the grand aesthetic conversation historically speaking: it is also a profoundly un-Catholic attitude, one that is sabotaging the sincere spiritual striving of many would-be saints. Music has both profound intellectual and moral dimensions. The New Evangelization cannot succeed with brigades of passive listeners imbibing whatever catchy tune is currently burning up the charts.

If Catholic music is found everywhere save Catholic Churches, it is perhaps even more rare in Catholic homes. In both matters of liturgical and personal music choices, it is essential to educate ourselves on the true nature and power of music, while engaging in an active discernment framed by the great masterworks of sacred music and music history in general. The thinking person does not merely absorb or “discover” their personal tastes: they form them intelligently. In the case of one seeking the Kingdom of Heaven, the intentional formation of taste takes on a spiritual dimension as well. The deep influence that music can hold over the soul of a person — and an entire nation — was long ago recognized by Plato, and has since been recognized by recognized saints, scientists, and more recently confirmed in the studies of psychomusicologists. A healthy first step in discerning music, therefore, is to prayerfully ask our Lord to be shown how powerful music truly is, and where it may hold inordinate power in our lives.

The Tyranny of Taste

I recently heard an undergraduate philosophy professor at a reliably orthodox Catholic college lament: “I have the best and brightest students, and they’re not afraid to question or challenge any presupposition that they may have. They are resistant in only one area: music. The moment I suggest that some discernment may be in order, they clam up and refuse to engage in critical thinking.”

This professor is describing the end-point in the hyper-personalization of musical taste: we are deeply territorial about our music. It is our own inviolable domain. For many it has the ambiance of a sacred escape from the cares and trials of the world, and it’s always just two small white earbuds away. To have another reform-minded person encroach upon this intimate place with critical analysis or moral jugments is often seen as an invasion, an act of aggression on our personal sovereignty. As such, a more tactful but equally honest approach may be in order.

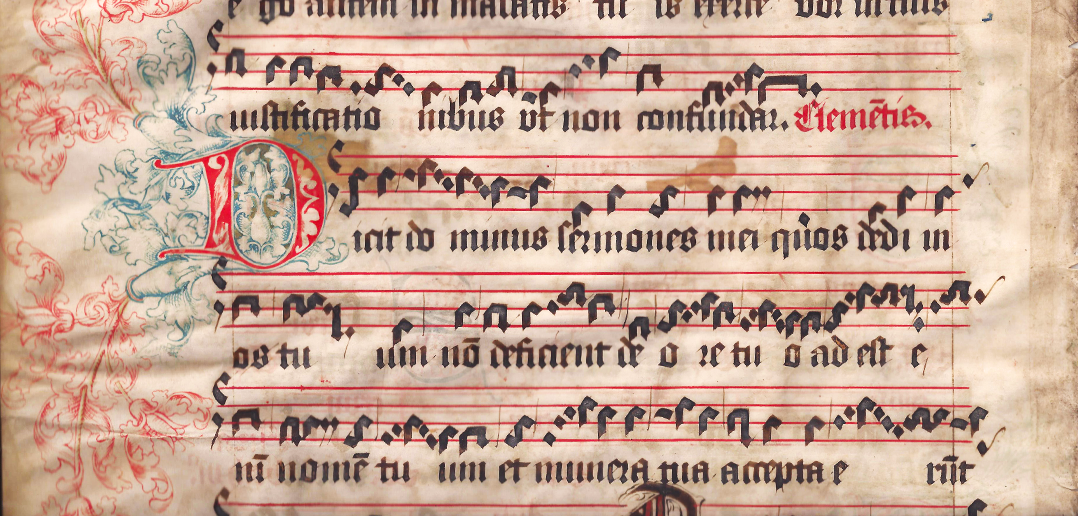

Consider that music is generally the last art to progress in history. As a member of the small but vibrant group of Catholics whose conversion was strongly influenced by the Church’s aesthetic heritage, I am left wondering when Catholics will shake off the webs of popular culture and wake up to the patrimony of their artistic heritage. Sacred music was called by the Church a “treasure of inestimable value,” yet the accompaniment of an average Sunday Mass shows a preference for plastic baubles over priceless diamonds. In our homes, many of us proudly play the soundtrack for the Kingdom of Relativism.

Still, there are signs of hope. After a long and often troubled era of unbridled innovation in both the sacred and secular aesthetic realms, the Catholic world is once again leading the way in the rediscovery of the good, the true, and the beautiful. Lead by a small but exponentially expanding worldwide rediscovery of authentic liturgy, music has found itself in the rare position of being at the forefront of a spiritual-aesthetic movement.

As Catholics are beginning, once again, to be exposed to beautiful – and beautifully sung – liturgy, a gradual reformation of personal tastes is blossoming. Starting within the musicians themselves and moving outward, a natural realization of the necessity of strong aesthetic discernment is taking place. Oftentimes this begins with a rather obvious (if often elusive) conclusion, such as, “I guess that my obsession with rap/death-metal/dub-step/hip-hop isn’t compatible with my desire to be a saint.” Hopefully what starts as an epiphany leads to action: recordings are tossed, digital music files are deleted, and a positive step towards the discernment of true beauty is taken.

The next movement of the heart and mind toward discernment becomes a prayer: “Lord, show me what true beauty is.”

Objective Standards – Beauty is Not Only in the Eye of the Beholder

Yet how does one discern individual musical choices, especially regarding the popular music which dominates our society? Before we proceed, it behooves us to examine C.S. Lewis’s brilliant and sensible Thomistic summations that 1.) every experience and interaction pushes us either closer to heaven or closer to hell -and- 2.) You can’t have even 1% of hell with you if you plan on going to heaven. Seen in this light, our listening habits take on a moral and formative dimension. Music and morality are intrinsically linked. Understanding this, Plato expressed a desire to control a society’s music as a means to shape the society itself. Many aspiring saints work heroically to root out the worst influences in their lives, but are unwilling to take a hard look at their music collection, or more often have no guidance on how to do so appropriately. How does one “grow up” as a listener?

It is not uncommon for those who desire to make a change to nonetheless take half-measures and half-considered attempts at aesthetic house cleaning. Certain Catholics will throw out everything “heavy” in their collection, drifting into the realm of easy-listening or at least mostly acoustic styles of music. Yet it is not a music’s “heaviness” that makes it moral or not beneficial, as a distorted guitar is no more or less moral than an acoustic one; there is also no shortage of “light” music that is either musically uninspiring or downright scandalous. Nor is heaviness in itself always undesirable: one can consider the astounding affect of the Dies Irae from Verdi’s Requiem as a famous example. Some folks step away from “dark music,” as if the conjuration of darkness or sadness in music were a universal negative. Consider the difference between the darkness of doom metal as opposed to the darkness of the original Dies Irae plainchant, or the difference between the atheistic hymn “Sound of Silence” and Henryk Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. In each of the first examples, darkness and sadness are talismans or points of departure, while in the Barber and Gorecki there is a concurrent redemption, an aural rendering of scriptures “tears changing into shouts of joy.” This is why experienced listeners will say that “people of depth find their joy in the saddest music.”

Others begin to avoid dissonance, as if two or more notes played together are somehow immoral, when it is ultimately the context and potential resolution of dissonance which is to be more deeply considered. Even the contentious area of rhythm, while powerful and able to bring about the worst in our lower faculties, is not a black and white issue. Syncopation may have lead to the sexualization of modern popular music, but it is also present in the great masterworks of sacred music.

Checkest Thyself, Before Thou Wreckest Thyself

So why does everyone from the Beatles to Beyonce inspire hip grinding and thoughtless movement, while similar rhythmic structures are used by Palestrina to bring our thoughts to the very edges of eternity? At issue here is culture, craft, and intent. Those with strong musical training can engage in a far deeper analysis of music (a good enough reason for the comprehensive Catholic music education of youth if ever there was one), but a layman’s consideration of these three basic categories can be a fine starting point for discernment.

A music’s culture is often part of a closed sphere of activity which must be viewed from the center of this metaphorical form, and not from anywhere in the actual continuum. We have long since arrived at the point where the imitation of life by art and art by life is generally indistinguishable. In considering a music’s culture, we must consider both from what manner of culture (or subculture) it emerges, and what cultural end it feeds or encourages. A consideration of most rap music, for instance, would reveal an artistic medium which emerges from the less culturally-developed areas of our society, and by its content and musical structure encourages base behavior; its continuum is a vicious circle which only reinforces the violence, misogyny, and confusion that it claims to decry. (The corrupt industry moguls who so effectively peddle any cultural trash for profit constitute a shadow culture related to this music which must also be considered.)

There is also something utterly peculiar and disgusting about our hyper-amplified popular culture. When in 1966 John Lennon garnered immense controversy by — claiming that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus”, fundamentalists stupidly burned records and called for boycotts, instead of engaging in an honest self-reflection about why their daughters were screamingly lasciviously at four scruffy young Brits on National television. The Beatles phenomenon is ultimately what woke the industry up to the full potential of musical mass-marketing, and we’ve been saturated ever since. This would later lead “The Who’s” Roger Daltry stating (accurately) that pop music would soon replace religion in the public sphere; several decades later, we have arrived at this point, while most Catholic families remain ignorant to the competing religions in their households. Most of the Beatles “screamy girls” grew up to become fawning mothers who fondly looked at similar behavior in their children and dismissed it as, “just a stage.” Lost upon anyone who would make such a comment is that they themselves have not outgrown this “stage.” Such is the thoughtless Pavlovian endpoint of most popular music culture, and it demands a serious reassessment.

Lyrics also fall under the category of musical culture. One must always consider if changing the words is enough to “clean” a musical preference (hint: it almost never is.) In the emergence of a musical style, lyrical content and musical construction are figuratively joined at the hip. Lyrics of violence, pornographic imagery, or the cult of radicalized self will always evolve alongside a musical language that is most expressive of these lyrics, and most effective in being a vehicle for the intended message. Ultimately it is not the lyrics but the music itself which changes the way a dedicated listener walks, acts, dresses, and speaks. As music is able to bypass the critical faculties of the untrained listener and penetrate to a far deeper (and some would argue, subconscious) portion of the psyche, ideas such as alienation or frustrated sexuality (or repressed violent urges) have a sound that is far more palpable and powerful than the words which may accompany it. Seen from another light, the words have little power without the tidal surge of music to carry them into us. If you doubt any of this for a moment, consider the peculiar phenomenon of ear-worms — songs that get stuck in your head, whether you want them there or not — and how even a snippet of music that you hate can start the endless replay anew in your mind for days on end.

Evaluating our personal tastes in music, and the underlying power that the songs we listen to has in our lives, is a challenging, perhaps even daunting undertaking. Not a few readers will have given up on this essay in frustration; others will even now be justifying to themselves why the music they enjoy must not fall under the sort of critical scrutiny I have suggested. The truth is, this is a difficult — and in some respects painful — process. And yet if we desire the edification of our senses, and even more importantly, sanctity, it’s something we must all consider.

In the next installment, I will discuss the craft of musical composition — the math, science, rhythm, structure, and critical analysis that making good music requires. In addition, we’ll look at a technique that will help cleanse the palate of music that is less than sublime and become sensitized to beauty again.