Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part series on the topic of cultivating a more authentic taste in music. The first part is available here.

In the last article, we discussed some of the criteria by which we may evaluate the quality of a piece of music. We will now move to a music’s craft, which involves the actual construction of the musical material itself. Composition is certainly as much a craft as carpentry or architecture, as it involves the combining of mathematical ratios into a structure that will either collapse, stand like a rickety shack, or tower mightily for the remainder of human history like a sonic Pantheon. These constructions can be analyzed, diagramed, and compared. Even simple music bears complex structures that cannot be understood without training. This is why trained musicians almost universally recognize the superiority of J.S. Bach’s music, while aesthetically inclined apologists have written the almost self-evident argument that: “J.S. Bach existed, therefore God must exist.” While one does not need to be musically trained to accidentally hit upon a good musical structure, it happens only slightly more often than illiterates dictating good novels. We have, therefore, a phenomenon that author Michael O’Brien called “canned music,” where most people are listening to musical structures created or performed by musical illiterates, a real “deaf leading the deaf” scenario. The result is that everyone is sold far short of what the experience of music can truly be, including the Catholics who are being called to lead the way forward into something far better.

A vitally important area of craft that everyone can discern regards rhythm. Have you noticed that rhythm is everywhere nowadays? Modern popular music simply cannot let a moment pass without filling it with driving rhythmic structure, while young music students arrive in class eager to “make beats.” Even children’s songs, when they are re-purposed for a modern audience, must have a constant attendant beat. The end result is that rhythm becomes the primary element of music, while harmony and melody become secondary considerations. This had lead to many forms of modern electronic music in which melody is largely absent and in which functional harmony has utterly disappeared. One can quickly discern, therefore, whether one’s music “breathes” naturally, or is in rhythmic overdrive. (Note: rhythmic drive is a primary tool in selling music, as it purposefully doesn’t give people space to think.) Discern, therefore, what is the goal of this rhythm? Is it intended to create aggression or exaggerated sensuality, or to simply drive a sub-par musical structure forward? Does it give me space to feel, think, and to be human?

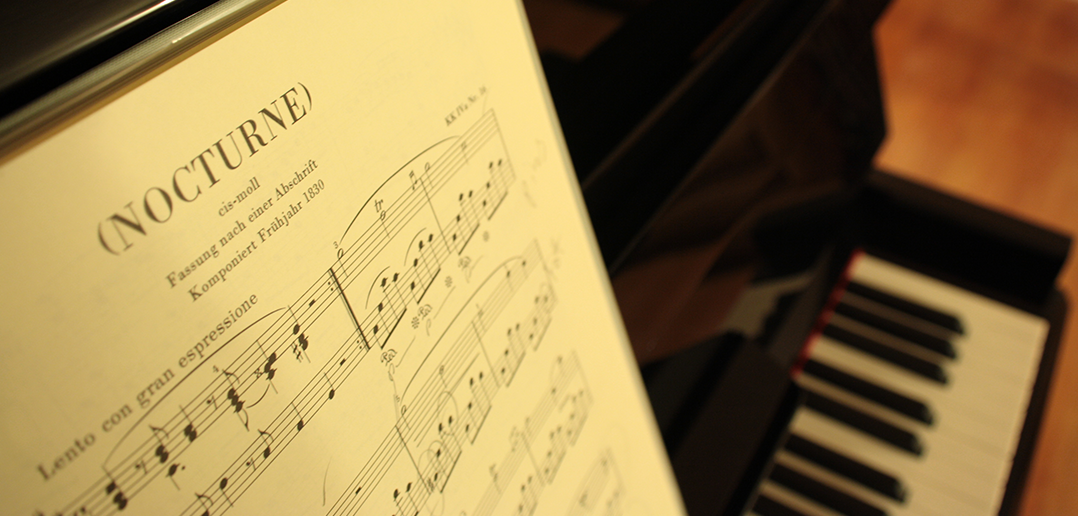

Finally, in order to discern craft, one need merely compare one’s favorite music with the masterworks. Can it be argued that your musical choices are both beautifully crafted and worthy of the spiritual and cultural patrimony defined by the greatest composers in history? All music may fall well short of Bach and his chief imitators, but does it even attempt to breath some of the same rarified air? Is it made by people who have studied the greats? It is a tall standard indeed, but one by which aesthetic weeds can be easily separated from the wheat.

Finally we come to a music’s intent, a simple area of discernment in which one must ask: who created your music, and who helped to propagate it? What is this music for? Are these people sympathetic to your spiritual goals, or at the very least somewhat neutral about your religion? The fact of the matter is that it is almost impossible to find popular cultural diversions that do not emerge as a direct result of an increasingly anti-Christian and relativized culture, with the specific goal of driving our perceptions further into this downward spiral. One may consider by contrast the music of modern composers Henryk Górecki or Arvo Pärt, whose works emerge out of silence, do only what is musically necessary, and return us to silence once again. In contrast to the noise and rage and glitz that is constantly at work to drown out our necessary silence, Górecki and Pärt’s music reverences holy stillness, and certainly emerges from dedicated lives of prayer and faith. Can your own favorite music claim such a pure intent? How much of your music is written and performed by those seeking sainthood?

When musical culture, craft, and intent come together, a music’s purpose and potential is revealed. This is why it seems to be so difficult to create beautiful rap music with edifying lyrics that will resonate in the broader culture, while it seems equally impossible to drag classical music down into the gutter (or the popular mainstream.) There is a reason that Beethoven will never be the soundtrack to urban violence (which is why Stanley Kubrick’s infamous Beethoven scenes remain so unsettling), and why we will never see a “Bieber Liturgy.” Remember: there are no neutral aesthetic experiences in our life. We are either moving towards heaven or towards hell, and our chosen soundtrack (like the best film score) is urging the action forward in either direction.

Sing a Song with Padre Pio

Doubtless many readers will continue to feel strongly resistant to these ideas, as they involve painful and intimate personal change in a direction in which the reader may have no aesthetic desire to move. Imagine then, for a moment, that St. Padre Pio, St. Augustine, and St. Paul walk in to your room to discuss aesthetics. Will they be edified by your music collection, or horrified? Will they joyfully share in your entertainment sources? Or to return to C.S. Lewis’s maxim: do you think that your favorite Led Zeppelin album will follow you into heaven, no matter how masterful John Bonham’s drumming was? Do you think that you’ll be allowed out of purgatory until the very last shred of Salt N’ Peppa’s “Let’s talk about sex” is burned out of your mind? Humorous as these images may be, they reveal the true import of our aesthetic choices.

The Great Aesthetic Fast

Undoubtedly modern man is faced with something unique: an almost omnipresent multimedia complex that assails us at every turn, leaving no room for critical reflection unless this room is wrested by force. Yet there exists in all of this discernment a possibility to – like a monk emerging from a cave after many years of isolation – become sensitized to beauty again, while also becoming rightfully sensitive to the things that are unfit for our consumption. Therefore as a final step to an authentic Christian aesthetic discernment, I suggest a long-term aesthetic fast, at least six months in duration. It may begin with a silent retreat, after which one simply shuts out all music, media, and popular entertainment for a matter of weeks. This may be followed by a gradual admission of plainsong (another name for Gregorian chant) and polyphony, slowly working up through to the sacred music of our day. Listening can be restricted throughout this fast to mostly sacred music, so as to feed the mind and soul with music of the highest craft and intent. Music should also be very limited, no more than an hour per day unless a live concert is attended (music students and professionals will obviously have to make concessions here.) While it is impossible to shut out all of our negative culture in this media-saturated world, the results of such a fast will certainly lead to a renewal of your senses. Beauty will be more palpable in its many forms, while ugliness and violence will be more repulsive. The fast-paced editing of television and the shattering glitz of shopping malls will become unbearable, while you will regain a proper appreciation of the disruptive power of noise and the edifying power of silence.

As to your relationship with music itself, it will not be curtailed or diminished, but rather improved exponentially. You will be able stand next to Mozart, understanding the workings of the inner man as an intimate friend would, all while gazing along with him unto the edge of eternity as shown forth in his famous Requiem. You will be able to mourn humanity’s loss with Arvo Pärt while listening to his Adam’s Lament, or join Mary at the foot of the cross with James MacMillan’s Seven Last Words, or feel the ecstasy embedded in Haydn’s Creation. You will stand by Mahler’s side in eternity during the triumphant final bars of his Resurrection symphony, joyfully storming the very gates of heaven itself. Perhaps most importantly, you will be able to find the very same seat where Augustine sat and was transfixed and literally terrorized by the beauty of plainsong. Perhaps the well-kept secret here is that much great music is spiritual ecstasy encapsulated, and it is available on a regular basis for those willing to come to it on its own terms. Finally, for those listeners lucky enough to attend a liturgy with well-executed music proper for the feast, you will find yourself perceiving the Mass as if for the first time. A bit of uncomfortable discernment is a small price to pay for a pearl of such great price.

It is among Satan’s greatest lies that the sinner will miss his concupiscence in Heaven. One will never find a person who has engaged in such aesthetic house-cleaning who regrets it, anymore than a blind person could regret having their sight restored after many years.

There is a purpose to the existence of music which powerfully echoes our origins and our destiny, and is capable of leading us – as Dietrich Von Hildebrandt said – “in conspectum Dei,” or before the face of God.