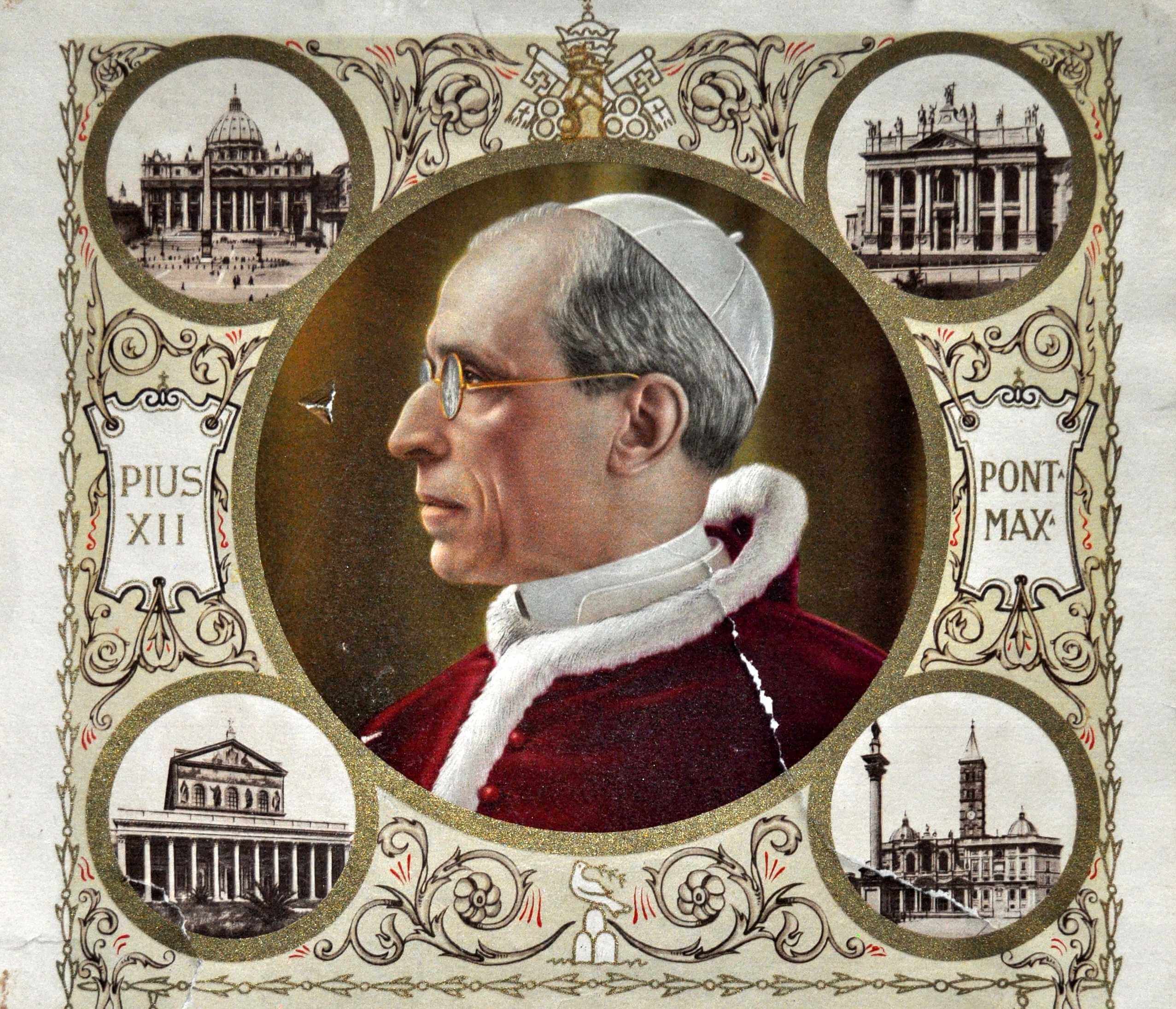

Back in May, I published an article at LifeSiteNews entitled “Coincidences during the reign of Pius XII? Political background to Vatican II and liturgical changes.” The article generated a fair amount of discussion, both favorable and critical. Since the pontificate of Eugenio Pacelli is so rich with historical interest and consequences, I would like to return to the subject with further observations.

In Roberto de Mattei’s The Second Vatican Council: An Unwritten Story (p. 217), we read: “De Lubac mentions two particularly critical opponents of the [liturgy] schema”: Archbishops (later cardinals) Vagnozzi and Dante. Dante, of course, had been the papal master of ceremonies since 1947. Vagnozzi’s intervention contains a passage that is poignant in retrospect:

The theological language [of what would become Sacrosanctum Concilium] often appears vague and sometimes inexact; I humbly maintain that the doctrinal principles of the liturgy, enunciated better and in a more cogent formulation by the supreme pontiff Pius XII in the encyclical Mediator Dei, can be repeated word for word by the Fathers of the Council, rather than the drafts that have been proposed to us.

In John XXIII: Shepherd of the Modern World, Peter Hebblewaithe notes that Ottaviani, in his famous rudely-interrupted speech, “protest[ed] about the way the authority of Pius XII was being misused.”

He granted that Pius XII was liberal and generous in admitting adaptations and the use of the vernacular in certain sacraments. But those who quote him in favour of the vernacular must have forgotten what Pius XII told the liturgical congress held at Assisi in 1956: “The Church has serious reasons for maintaining firmly and unconditionally”—note those words, firmly and unconditionally—“the use of the Latin language in the Latin rite.” So [continued Ottaviani] if you want to use the authority of Pius XII, use it not just when it agrees with you. Use it honestly. (ASCV, I, 2, p. 20). Ottaviani saw himself as the faithful guardian of Pius XII’s memory.

In connection with the controversial Pacellian Holy Week, in force from 1956 to ca. 1970, I believe it is possible that Pius XII may have never celebrated the reformed Holy Week himself—at least not publicly. If one views the British Pathe news reels of Pius XII’s Easter Blessings from 1939 to 1958 (not to be confused with various “Easter Message” videos, the most famous of which was given the day before the Italian elections of 1948 in April), one can see that in the 1939, 1940, 1946, and 1950 Easter Blessings Pius XII is fully vested with assistants, flabella, etc. From 1951–1958, there is an “Easter Blessing” video for every year; in each one, Pius is vested only in rochet and mozzetta. He has two or three unvested assistants. If Pius didn’t celebrate a public triduum, would the dean of Cardinals have celebrated it in Pius XII’s presence? Would he have been at the ceremonies at all? Might he have celebrated a “private” Triduum?

The Rad Trad, a severe critic of Pius XII’s liturgical tampering, himself says: “By 1950 his [Pius XII’s] health was in rapid decline and he began using low Masses or had cardinals celebrate public Masses in his presence.” The British Pathe commentary for the 1956 coronation anniversary of Pius XII observes: “Normally, the ceremony takes place on a smaller scale in the Sistine Chapel, but this is a special occasion, because it is the first time in three years the pope’s health has permitted him to be present and also because it takes place following the celebration of his eightieth birthday.” Annibale Bugnini himself mentions in The Reform of the Liturgy that Pius XII was so weak he couldn’t finish reading his speech at the Liturgical Conference in Assisi in 1956—someone else had to finish reading it for him. At 5’20” in this video, it is definitely evident that Pius XII’s health had deteriorated to an abysmal state.

In The Organic Development of the Liturgy (pp. 236–37), Dom Alcuin Reid notes the difference in tone between the Holy Week decree and the sacred music encyclical, both promulgated in 1955:

Published in the shadow of the reform of Holy Week, the encyclical’s lack of explicitly “pastoral” language similar to that of Maxima redemptionis nostrae mysteria and of its accompanying instruction is of interest. Firstly, the encyclical was a papal document and not the work of the Pian commission, though there may have been some coincidence of personnel in drafting. Alternatively, it may be an indication of divergent thinking within the Holy See itself as the work of liturgical reform progressed. . . Those in the Liturgical Movement who so self-consciously spoke of the “pastoral Liturgical Movement” risked subjectifying objective liturgical Tradition and refashioning it according to contemporary desires. Such a path is alien to Pius XII’s Musicae sacrae disciplina.

The implication is that we can detect more interference from the proponents of a “pastoral” Liturgical Movement in the Holy Week reform than we can in the sacred music document, which better reflects Pacelli’s own conservatism on the subject.

What we can say for sure is that more attention needs to be given to the maneuvers of certain of Pius XII’s subordinates during his decline, especially Monsignor Montini; it is impossible to understand the promulgation of a new Holy Week without such realism. Father Charles Murr’s The Godmother, de Mattei’s The Second Vatican Council, and Fr. Luigi Villa’s Paul VI Beatified (which was endorsed by Alice von Hildebrand) all contain examples of Montini deceiving (“working around”) Pius XII. After Montini was “promoted” to Milan, his replacement in the Secretariat of State, Monsingor Dell’Aqua, was, according to Roberto de Mattei, “considered Cardinal Montini’s representative in Rome.”

Could it have been Ratzinger’s knowledge of the harm that was done at the end of Pacelli’s pontificate—and not merely his close observation of the jockeying for power during the long twilight of Wojtyła’s reign—that partly explains his choice to abdicate the papal office? History has already borne authoritative witness, in any case, that giving up the papacy in the hopes of a better successor is a dangerous gamble.

As Alcuin Reid documents, Cardinal Siri was one of the bishops who contacted the Vatican objecting to the initial Holy Week tryout in 1951. Cardinal Spellman opposed the mandated new Holy Week in 1955. Both of these prelates were close to Pius XII. One wonders if Pius XII ever received their protests. There is an old saying: “A bishop is one who never has a bad meal and never hears the truth.”

Now, concerning Siri, there are significant facts regarding him which, surprisingly, go unmentioned in de Mattei’s book on Vatican II. We know from reputable sources that Pius XII hoped Cardinal Siri would succeed him as pope; he’d even been called “the Dauphin of Pius XII.” In Benny Lai’s book on Siri, Il papa non eletto, it is revealed that Cardinal Gaetano Cicognani was a significant supporter of Siri’s candidacy in the 1958 conclave. This Cardinal Cicognani was prefect of the Congregation of Rites when the new Holy Week was promulgated and signed the mandating document. According to Lai, “it was Cardinal Gaetano Cicognani who circulated the news that Pius XII had indicated as his successors Siri or Ottaviani.” The Dominican Raimondo Spiazzi, in his work Il Cardinale Giuseppe Siri, Arcivescovo di Genova dal 1946 al 1987, quotes Siri testifying to “Pius XII’s special fondness” for him, in words that are rather mysterious:

You see, we understood each other. He was a man of government. The greatest, along with Cardinal Boetto, that I have known in the Church. Government leads to putting the right men in the right places. Receiving them all, letting them talk, listening to them and meditating. Government is done at the table. I learned from them. That’s why I receive all my priests and talk to them. That’s why every Wednesday I’m at my seminary and I receive everyone. I never ask questions. I listen. And I am able to know and decide for the good of the Church. As for Pius XII, now I can say it: twice he asked me to leave Genoa and come to Rome. He feared that he might be a victim… and he wanted a person of complete trust to help him. Not as Secretary of State. Less and more. The second time I was convinced. But the Lord took him to Him.

Considering Pius XII’s failing health; his indecision in the 1950s; the consequential bad management of the Vatican; Pius XII’s mistrust of certain people, including Montini; and Siri’s orthodoxy and brilliant intellect, one cannot help but be saddened that Siri did not accept Pius’s request to join him in Rome the first time. Then again, it is not hard to see why Cardinal Siri might not wish to leave Genoa or work in the Vatican.

Siri, in any case, was persuaded of Pacelli’s virtues. Elsewhere in Spiazzi’s book we read:

Siri loved to recount certain episodes of his relations with Pius XII, as well as of those with his successors. It was evident that he had an unconditional admiration for Pius XII and was certain of his superior wisdom and holiness. Indeed, he was the leading Cardinal in the cause of canonization of that angelic pontiff. Confidentially, he said that he was not unaware of some of the objections of the “advocatus diaboli,” but that he was convinced—as we are all convinced—of their inconsistency.

In her memoirs His Humble Servant, Madre Pascalina mentions Cardinal Siri’s speech on Pius XII’s eightieth birthday in 1956:

We were looking forward to the afternoon, when a celebration in honor of the Holy Father was scheduled in the Palazzo Pio XII. The splendid music added to the festive atmosphere in the packed hall. When Cardinal Siri then mounted the rostrum and with warm words painted a picture of the life of the Holy Father, displaying not only his beautiful use of language, but, above all, his deep affection and genuine admiration for the object of his praise, the applause in the large hall was overwhelming.

Luigi Villa quotes another of Raimondo Spiazzi’s reminiscences of a conversation with Cardinal Siri, this time about the influence of Freemasonry, and Siri’s belief that the papal conclave should be made a non-secret event:

As to the conclaves of the future, Siri used to say one should pray in order to obtain the grace that the participants be truly free from any partisan influence, not only of an ethical and political nature, but even social—and that no sect lay its hand on these conclaves. He was referring to Freemasonry, of which he claimed to have knowledge, through direct confidences received by affiliates, about the schemes through which it attempted to tighten its grip on men and organs of the Vatican (he did not hesitate to name a few), and with the danger that it threatened to extend its grip to the conclave. Perhaps it was also on the account of that that he proposed the abolition of the secret—so that all will take place in broad daylight!

Returning to Pius XII, Madre Pascalina quotes Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber, who said to her after witnessing a pontifical Mass by Archbishop Eugenio Pacelli: “I have just attended the most moving Mass in my life. Only a saint can celebrate like that.” To which Madre Pascalina replied: “It’s the same experience every day, Your Eminence.” (Recall that Madre Pascalina was Pacelli’s housekeeper and secretary from 1917 until 1958!) Much later, when Pius XII was elected pope, Cardinal Faulhaber said: “Do you remember the first Holy Mass celebrated by the young Nuncio Pacelli that I attended back in Munich at the Catholic Congress? At the coronation ceremony today I saw the same unforgettable picture: a saint celebrating Holy Mass. He is certain to be one of our great Popes, but I also know that we have a saint of a Pope!” (Cardinal Faulhaber, incidentally, is the prelate who ordained Joseph Ratzinger to the priesthood in 1951.)

Given such glowing testimonies, it has long been taken for granted by conservative Catholics that we had in Pius XII a great saint who deserved rapid canonization. Sadly, in light of the now-routine political abuse of beatification and canonization in recent pontificates, we may well consider it providential if the “saint factory” ever slows down, allowing a careful sifting of the records and an accurate evaluation of the positive and negative aspects of any pope’s reign. After all, the robust “advocatus diaboli” is no more. There is plenty yet to be discovered about how much mischief his subordinates did under the cloak of papal protection.

English speakers may regret the fact that many important sources on the pontificate of Pius XII and his circle are only in Italian: Il Cardinale Giuseppe Siri, Arcivescovo di Genova dal 1946 al 1987; Il papa non eletto: Giuseppe Siri, cardinale di Santa Romana Chiesa; Nichitaroncalli: Controvita di un papa; 18 aprile 1948: Memorie inedite dell’artefice della sconfitta del Fronte popolare; Il “Partito romano” nel secondo dopoguerra, 1945–1954; as well as one that is only in French, Pie XII devant l’Histoire. There seems to be an abundance of information that is simply not available in English.