When Pope Francis issued a motu proprio called Traditionis Custodes on 16 July 2021, an edict severely restricting the celebration of the Traditional Latin Mass, it marked the culmination of the growing official hostility towards the Apostolic Roman Rite (hitherto referred to as the ‘extraordinary form’ of the liturgy). This term, which had been invented by Francis’ predecessor, Benedict XVI, was banned by Francis in his new edict. In January 2019, the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei, which oversaw the priestly communities and faithful attached to the ancient Latin liturgical tradition, was suppressed by Pope Francis, and its responsibilities were incorporated into the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF). At the time, the Vatican presented this change as part of a ‘normalising’ of relations with traditional Catholics. However, traditionalist Catholic observers were rightly wary. Much more ominous was the nine-point questionnaire, subsequently sent by the CDF to the world’s bishops in March 2020, asking such leading questions as: “In your opinion, are there positive or negative aspects of the use of the extraordinary form?” The survey also asked whether the extraordinary form responded “to a true pastoral need” or whether it is “promoted by a single priest.”

Many traditional Catholics immediately saw this survey as forewarning of a much more aggressive papal policy regarding the Apostolic Roman Rite and the small but fast-growing traditional communities that have arisen around it. It is interesting to note that the eponymous ‘Benedictine Peace,’ following Pope Benedict XVI’s 2007 liberalising policy towards the Old Rite, extended for eight years of Pope Francis’s pontificate with little indication, until 2018, that this ancient liturgy would be targeted.

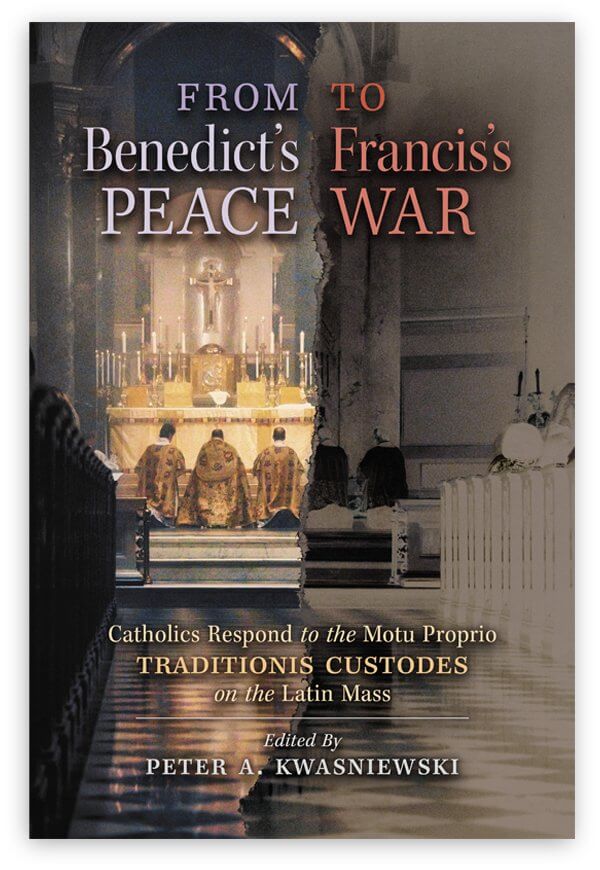

The American traditionalist Catholic theologian, philosopher, and composer Peter Kwasniewski has been a major figure in the flowering of the ‘traditional movement’ during the 14 years of this fragile Pax Benedictina. Therefore, it is unsurprising that he was perhaps best placed to gather, edit, and publish some of the flood of reactions to Traditionis Custodes in this anthology, From Benedict’s Peace to Francis’s War, in October of 2021.

This book is undoubtedly well timed to respond to what is one of the most important moments in the Church’s history in the post-Vatican II epoch. It was published after the opening bombardment in the next phase of this war, but with the prospect of further Roman Curial attacks on the former Ecclesia Dei communities, some might regard the book as somewhat premature. Fortunately, the book is not likely to become dated anytime soon, largely because—as one might expect from traditionalists—many of the essays look backwards as well as forwards, and meditate on the timeless quality of the Apostolic Roman Rite.

Kwasniewski marshals an impressive array of voices to dissect and repudiate Traditionis Custodes, including various theologians of the School of Salamanca and more modern thinkers like St. John Henry Newman. The essays examine and critique Pope Francis’s motu proprio through a variety of juridical, political, ecclesiological, philosophical, theological, and, of course, liturgical prisms. It was particularly edifying to hear from non-Anglophone authors in this volume; the reader is able to hear from important traditionalists such as Juan Manuel de Prada of Spain, Martin Mosebach of Germany, Massimo Viglione of Italy, and Abbé Claude Barthe of France. Their writings offer several incisive contributions and give a more universal voice to the traditionalist cause, which often seems dominated by American perspectives, a caricature one suspects has purchase among several Vatican officials.

It is noticeable that many of the book’s Anglophone contributors are almost bewildered by the sudden papal attack on the traditional liturgy. This is a shortcoming of the Anglo-centric perspective, which underestimates the depth of the antipathy towards the Apostolic Roman Rite amongst many non-Anglophone bishops. Following Summorum Pontificum in 2007, one Italian bishop said:

This day is for me a day of grief … I do not manage to hold back my tears … Not only for me, but for many who lived and worked in the Second Vatican Council; today, a reform for which so many laboured … has been cancelled.

The reality is that the ‘Benedictine Peace,’ initiated by a gentle shepherd so that the Church “might be at one with herself,” was never accepted by many hierarchs in the neo-modernist wing of the Church. For them, the Second Vatican Council really was the revelation of a new religion, and the Rite of Paul VI was its celebration. For these clergy, the fourteen years between Summorum and Traditionis was not a ‘peace’ but rather a temporary quietening of hostilities, a pause to regroup after a highly damaging enemy bombardment, before launching a fresh assault on those who continued to resist the ongoing ‘aggiornamento.’ Thus, many Italian, French, and Latin American bishops routinely contradicted Summorum, suppressing priests offering the traditional Mass in their dioceses during this period. Summorum Pontificum had yet to arrive when Traditionis Custodes was issued!

There is a diverse selection of essayists in the volume, who often disagree on important points. The broad division is between ‘moderate’ writers, who largely maintain Pope Benedict’s ‘hermeneutic of continuity’ regarding the Second Vatican Council and are keen to stress that they only desire that the Apostolic Roman Rite ‘mutually enrich’ and ‘co-exist’ alongside the Rite of Paul VI, and more strident traditionalist writers who do not shy away from arguing for the Old Rite’s objective superiority over the new. It is entertaining to read essays from the moderates sat alongside those from ‘firebrands’ like Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano and Italian essayist Massimo Viglione. Kwasniewski’s own voice emerges most clearly from the chorus of writers with six contributions, describing the motu proprio as the worst papal document in history—one gets the sense that he sits in the latter camp!

Nonetheless, several themes recur throughout the volume. To take three of these: first, many authors see Traditionis Custodes as a providential moment in discerning the moral limits of the Supreme Pontiff’s universal ordinary jurisdiction. They agree that the pope’s authority is bounded to and limited by Tradition, and that a remote cause of today’s crisis has been a mistaken hypertrophic understanding of the papacy as the ‘Absolute Monarch’ of the Church rather than as the guardian and servant of that Sacred Tradition. Pope Francis’s Jesuitical papal absolutism has taken this tendency to its absurd conclusion, promulgating a document that implies that not only can the pope arbitrarily dispense with ancient traditional rites and norms, but that the pope is Tradition itself (la tradition, c’est moi). Basically, he gets to decide what Tradition is— and if the pope says it, it must be true.

Second, and this is closely related to the first theme, is the scourge of clericalism. As one anonymous author writes,

those who most vociferously promote a democratic view of the Church are often the ones most inclined to defend the clericalist power structure of the Bergoglio Vatican, in which a narrow court of fawning sycophants disregards the ‘little people’ and imposes rigid norms from on high.

This Nietzschean triumph of the will, where the liturgy is seen as belonging to the clergy rather than the entire faithful, is something that allowed for the liturgical revolution to be so sweeping in the 1970s. Yet, in our own time, many of the Catholics most actively fighting to defend the Apostolic Roman Mass are laity, as evidenced by this book.

Third, many authors argue that Francis’s militant hostility to the traditional Mass manifested in the motu proprio is error-ridden and canonically slipshod. Cardinal Walter Brandmüller reminds readers that doubtful law does not bind. Since it is based on multiple apparent falsehoods, contradictions, and ambiguities, the liceity of the document is highly questionable. This also seems to be the quiet view of more than a few bishops across the world who have already granted provision for the continued celebration of the Apostolic Roman Rite and discreetly shelved the motu proprio for the time being. By historical standards, papal power is in decline, and Pope Francis can no longer bank on the immense respect given to the papal office in 1969. In postmodernity, everything is accelerated, and it seems that the effects of Traditionis Custodes might not endure much longer than the generation of 1968, among whom are its authors and enthusiasts.

There are layers of complex motivations in the Vatican hostility towards the ancient liturgy that the book attempts to unpick. In 2017, Antonio Spadaro S.J., editor of the Jesuit journal La Civiltà Cattolica and papal confidante, wrote an opinion piece in that magazine which offered a window into how those from the neo-modernist wing of the Church— and probably the pontiff himself—see politics. In his essay, Spadaro savagely criticises the alliance between the “evangelical right,” “Catholic Integralists,” and the Trump movement in the United States. He accuses this alliance of being guilty of all sorts of sins, including “vindictive ethnicism,” spreading a “Prosperity Gospel,” and abetting an ecological crisis, all in the service of a belligerent American Empire. In Spadaro’s mind, Francis is “carrying forward a systematic counter-narration with respect to the narrative of fear” and positioning himself against this American “ecumenism of hate” alliance. In my opinion, it was this worldview of figures like Spadaro and others that had an important influence in the decision to promulgate Traditionis Custodes. By diminishing the importance of temporal politics, one risks acquiring an incomplete picture of the causes of the motu proprio. Traditionis Custodes is clearly part of a wider clerical programme of promoting a liberal worldview—the foundational worldview of ecclesiastical policy for the last half-century or so.

With its liberalisation, the Traditional Roman Liturgy was taken up as a rallying standard by American Catholic figures during the Benedictine convalescence. Some of these figures subsequently became deeply associated with the Trump campaign and the wider ‘nationalist-populist’ movement. Between 2007 and 2021, the Traditional Rite was accepted by at least a part of the American Catholic ‘conservative establishment,’ including influential organisations like Opus Dei and the Catholic television network EWTN. Through the activities and discourse of a constellation of figures and organisations like Archbishop Vigano, Church Militant, and Taylor Marshall, I suspect that the Traditional Liturgy became conflated with the Trump phenomenon in the minds of many Roman Curial officials. This association with the Right in America deeply antagonised the social-justice ‘left wing’ of the Catholic Church, associated with Jesuits like Spadaro and various communitarian movimenti such as Focolare. In September 2021, Pope Francis revealed his own sympathies when he directly attacked EWTN for carrying out “the work of the devil” by giving a platform to prominent conservative critics of his pontificate. Traditionis Custodes can partly be seen as an anathematization of this ‘right-wing’ trend by Pope Francis, and this would help explain the timing of the edict—after over seven years of largely ignoring the burgeoning Traditional movement.

There also seems to be a connection between the COVID crisis, the subsequent unprecedented closure of nearly all Catholic churches across the world, and the promulgation of this motu proprio. This coincidence seems an important one. Whatever one’s opinion on government responses to the COVID-19 outbreak is, the past two years have seen an escalation in the mistrust many people in the West feel towards the ‘international liberal democratic order,’ an order to which the Catholic Church’s officials have firmly aligned the institutional Church since World War II. Hostility towards the prerogatives, policies, and ‘values’ of this global power structure do cluster among Traditional Catholic parishes. Neo-modernist bishops are therefore not wrong to see the Traditional Mass as a growing threat to the liberal order, to which they have conceded almost all social, moral, and cultural authority.

Appropriately for a book edited by a composer, the essays mount, rinforzando, like a pleasing piece of music. The early essays in the book begin with particulars—that is, with the details of the promulgated motu proprio. The book then steadily builds to a crescendo as the writings increasingly examine the event at the root of nearly all the Church’s questions and struggles today: the Second Vatican Council. Kwasniewski has clearly ordered the essays in this manner. The book ends with some suggestive essays on “The Council’s last stand” and “Can a Catholic have doubts about Vatican II?” Pope Francis mentioned the Second Vatican Council 13 times in his accompanying Letter to the motu proprio. At the heart of the Letter he wrote:

I am nonetheless saddened that the instrumental use of Missale Romanum of 1962 is often characterized by a rejection not only of the liturgical reform, but of the Vatican Council II itself, claiming, with unfounded and unsustainable assertions, that it betrayed the Tradition and the ‘true Church.’

The Council was about the Church’s relationship to modernity, and this is clearly where the real battle persists. As Cardinal Ratzinger himself wrote in his Principles of Catholic Theology:

This text [Gaudium et Spes, Vatican Council II’s Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World] plays the role of a ‘countersyllabus’ [that is, to Pius IX’s Syllabus of Errors, 1864] insofar as it represents, on the part of the Church, an attempt at an official reconciliation with the new era inaugurated in 1789.

The Traditional movement clearly represents a threat to that ‘reconciliation’ (some would say surrender), which is a problem for bishops who have made effecting that reconciliation their entire lives’ work. The traditional liturgy is therefore hated because it is the visible reminder of the ‘before’ time—the visible reminder that the Church did not begin in 1962. This is a point clearly made by Sebastian Morello’s contribution, “Revolution and Repudiation: Governance Gone Awry,” which was first published as the essay “Reflections on Pope Francis’s Motu Proprio Traditionis Custodes” in The European Conservative.

A most eloquent essay in the book, penned by an anonymous priest, points out the irony of the fact that, by formalising the “hermeneutic of rupture” even further, Pope Francis and the neo-modernists are showing their hands and exposing the entire conciliar experiment to be a failure. Perhaps the providential fallout of Traditionis Custodes will be that more bishops will begin to ask those questions that Church officials have heretofore excluded: is Vatican Council II the most solid basis for the renewal of the Church in the 21st century? And, given the collapse in every Catholic metric over the last fifty years, are we permitted to question the relationship between the tree and its fruits?

Reprinted with the kind permission of The European Conservative.

Photo credit: Vatican Media.