Above: Cliffs of Moher, Lislorkan North, County Clare, Ireland

Part 1: Erin’s Green Isle

It is amazing how much of the American psyche is bound up with the nations of the British Isles – the traditional “Three Kingdoms” of England, Scotland, and Ireland, with Wales, Cornwall, the Isle of Man, Jersey, and Guernsey. With us, as with Anglo-Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Anglo-South Africa, the Anglo-Caribbean, and for that matter the Indian Sub-Continent to a great degree, our national pre-history is bound up – as are much of our art, architecture, literature, and customs – with their place of origin, those little islands in the stormy North Sea.

I have visited them many times, and – as with the rest of Europe, that Mother Continent from whence most of us Americans have sprung – always have a strange sense of homecoming when I do. The conflicts that have historically wracked the British Isles – latterly, that of the Protestant Revolt in the 16th century and the Civil Wars a hundred years later – determined the religious, cultural, and political history of the United States, as the settlers brought the conflicts between Celt and Saxon, Protestant and Catholic, Calvinist and Anglican, republican and Royalist with them to the New World. So too did they bring the folk memories of St. Patrick, King Arthur, Robin Hood, and all the rest with them. All of these haunt and shape us still, as they did our civil wars of 1775-83, and 1861-65.

It was a year ago last September that I visited Glastonbury for the first time in three decades – the Isle of Avalon, where legend tells us that St. Joseph of Arimathea first brought the light of Catholicism to the heathen Celtic Britons, along with a relic of Christ’s Blood. Sticking his staff into the ground when he arrived at Wearyall Hill, it took root and blossomed. Cut down by the Puritans during the Civil Wars, its cuttings survive, and still bloom at Christmas as their parent did; some of the blooms are sent to the Monarch then and are sometimes to be seen in the Royal Christmas Message. The relic of the Precious Blood supposedly continues to tint the waters of the Chalice Well a slight red. Either way, St. Joseph’s heritage was continued in the great Abbey of Glastonbury, where King Arthur’s grave is shown, and whose abbot was martyred with a pair of companions by Henry VIII. Although in recent years the town has become a New Age centre, the Catholic shrine continues to offer the Sacrifice of praise to God, despite the Bishop recently driving out the Benedictines who had recently resettled there, due to their adherence to the Traditional Latin Mass.

That experience was very much on my mind when a school chum suggested we go the Isles for Spring Break. I agreed, and we left Austria behind, flying into Dublin. We arrived on a Friday night, and the following morning began our tour of Dublin. First place on the agenda, after a walk down O’Connell Street, was the Bank of Ireland – up until 1802, the home of the Irish Parliament. In that year, the act of Union was passed with Great Britain, which merged the Irish Legislature with the one in Westminster. At that time, the old building was given to the Bank.

They turned the House of Commons chamber over to business, but kept the House of Lords room intact. There is a poetic irony in this. Catholics could not vote for the Irish Parliament after the conquest of the Isle by King William in 1690-92. Although soon suffering buyer’s remorse, in 1802 they supported the Union, hoping for a better deal from Westminster than they could expect from the solid Protestants who made up the Irish Commons. But Ireland’s own House of Lords numbered many members of ancient Gaelic and Norman noble clans; they often had apostatised in order to hold on to their properties and privileges, and yet had may Catholic relatives – and so did what they could to mitigate anti-Catholic legislation. Looking at the Speaker’s chair and the mace in the Lords’ chamber, it seemed to me a minor blessing that it had survived.

Sunday found us at Traditional Mass at St. Kevin’s Church, Harrington Street. It is a beautiful church, and one would think untouched by the post-Vatican II wreckovations.

But the truth is far different. It suffered as badly as any church in the Emerald Isle. But after it was made over to the Latin Mass by the Archdiocese of Dublin, its new congregation sought out the original plans from the National archives, and completely restored the church to its original appearance. The choir was lovely, and the congregation devout. After the Mass we met old friends and new, and I was grateful for this remnant of the old Irish piety that has slipped into oblivion in so many places. We then went to St. Stephen’s Green, where so many died in 1916.

Monday, we explored Dublin further. We saw Trinity College, for years the Oxbridge of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy; to-day there is a Blessed Sacrament chapel in the English Baroque college chapel; one can only wonder what such alumni as Oliver Goldsmith or Oscar Wilde would make of it. We then made our way to Dublin Castle, where the Lords Lieutenant reigned over the British administration of the island. The lovely State Apartments remain intact, including St. Patrick’s Hall, where once the Viceroy presided over a gala ball on St. Patrick’s Day, and where the Irish presidents are now inaugurated. Here too is the Thorne Room. Its titular chair once seated the Lord Lieutenant when presiding over its court, and occasionally the Monarch himself. Its leg are short; after King James II was defeated and William of Orange took his place, they had to be cut – the Dutch usurper was much shorter than his Stuart Father-in-Law. Then we saw perhaps the most poignant building of all in the complex – the Chapel Royal.

An accurate reflexion of rulership over Ireland, it was Anglican until 1942, when it was reconsecrated as the Catholic Church of the Holy Trinity. But in recent years, it has become a non-denominational worship-space. I could not help but wonder what would have happened had James triumphed at the Battle of the Boyne, and Ireland remained a Catholic Kingdom – albeit one that tolerated its Protestant minority. Would two thirds of the Irish have supported abortion and gay “marriage?” We moved on to the now Anglican Christ Church Cathedral, and venerated the heart of St. Lawrence O’Toole, the medieval Archbishop, which remains enshrined there.

In any case, the following day, we left Dublin’s fair city and the Molly Malone Statue, for the seat of Gaelic Monarchy in Ireland, the Hill of Tara.

As with Glastonbury Tor, the feeling of standing by the Lia Fail, where once Ireland’s High Kings were inaugurated, was difficult to describe. As with its counterpart in Somerset, the feeling of ancient Sovereignty and modern Sanctity is almost palpable, despite all that has happened since. There are very few structures left at the site; “the Harp that once through Tara’s halls” is silent, but the tune ran through my head. Not all the New Agery in the gift shop could quite shut it out.

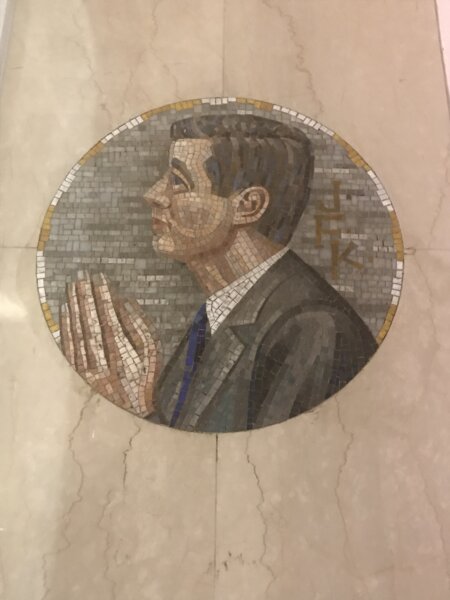

We drove on to Galway, and saw among other things the cathedral, consecrated by Boston’s own Cardinal Cushing in 1965. The last great stone cathedral built in Europe thus far, it epitomises the Church of my childhood – between Vatican II and the promulgation of the New Mass, when Catholics were very unsure of where things were going, but the cultus of Our Martyred President, JFK, was in full swing. Indeed, in the wall there is a mosaic of him praying. Memories filled my head of that time, and what it engendered. I staggered out in a sombre mood.

That night, with a local friend, we went to the King’s Head, a fine old restaurant and pub. It soon turned out that the name proudly commemorates the fact that Charles I was beheaded by a Galwayman, as they could not find a native Englishman to murder him. Left out, of course, was the fact that said executioner was a Protestant, or that he swung the axe at the behest of Cromwell, who shortly after that triumph would make all of Ireland pay for her loyalty to the King. The blood of an English Monarch presaged the floods of Irish blood that flow as a result. We hit a number of pubs afterwards that advertised “traditional music;” but it was at first anything but. In one, after the band did an Elvis tune, I offered to sing with them, and we did “The Boys of Kilmichael” and “Sam Hall.” The oldest musician there grabbed my hand and thanked me when we had done, and the audience were appreciative!

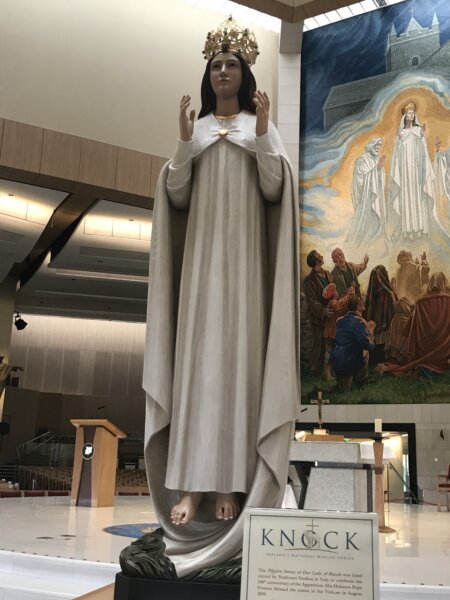

The following day we drove to Knock, and venerated the site of Our Lady’s apparition.

It is a holy spot, to be sure, if not the most attractive. We prayed to the Queen of Ireland for her people – both in Erin and around the world. We then moved on Drumcliff, where Yeats’ grave lies in Drumcliff, under the height of Ben Bullen. A strange man, to be sure, but a fine poet, I thought of his entirely too prophetic “The Second Coming.” But I also thought of “the Fiddler of Dooney,” with its hopeful line “the good are always the merry, Save by an evil chance…” I said a prayer for him, in hopes it would do him some good.

We crossed into Northern Ireland; there I was haunted by the way abortion had been foisted on Ulster. In the south it was brought in by referendum; in the North it was foisted upon an unwilling majority of both Catholics and Protestants by an unholy pact between Her Majesty’s Government and Sinn Fein. It was a sobering thought that the two enemies found shedding the blood of infants to be a ground of unity – it spoke badly for them both.

But the North is as enjoyable to the visitor as the South. The one major difference we found is that in the many pubs we visited in the Republic our fellow drinkers inevitably asked where we were from; the clientele in the North were just as fun and friendly – but never asked that question. I could only suppose it was a remnant of the Troubles. At any rate, after a marvellous dinner in Enniskillen and a very disappointing would-be lodging in the mountains, we found a hotel in Omagh. The next morning we set out to visit for the next couple of days Roger and Kim Buck – old online friends neither of us had ever met. They were superb hosts, and Roger, author of The Gentle Traditionalist and its sequel was a wonderful conversationalist. Having converted from the New Age, Roger and his wife were a lot of fun joking about it.

Our time with them having been spent, we set off for Belfast, driving through valleys empty of habitation but guarded by rainbows most of the way. In one particularly empty stretch of road, I noticed a fairy rag tied to a tree along the highway. Really, it would have been easy to imagine fairies in that glen – and apparently the few locals in the area were respectful of them. We did not tarry, but hurried on to the home of the friends we would stay with on the outskirts of Belfast.

I must admit that growing up seeing the troubles on Television, and hearing what one heard about both the Provos and the Orangemen during that era, I was not impatient to go to Belfast – although recognizing that my fears were of a reality from decades in the past. Indeed, my apprehensions were pointless. The next was Palm Sunday, and we went to Immaculate Heart of Mary, the church in Belfast of the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest. The Mass was in the pre-1955 version, with the elaborate series of blessings of the palms and folded chasubles. It was an inspiring and elevating moment.

After Mass we went to a pub dating back to the 1890s called “the Crown and Shamrock.” This unitive name spoke well of an institution that survived the troubles while catering to a clientele made up of both sides. The Sunday crowd was made up of families just come from Mass or service. It was a pleasant interlude, to be sure – but all too short. We drove off to the airport to fly to England, of which Kingdom, you’ll see more in the next instalment.