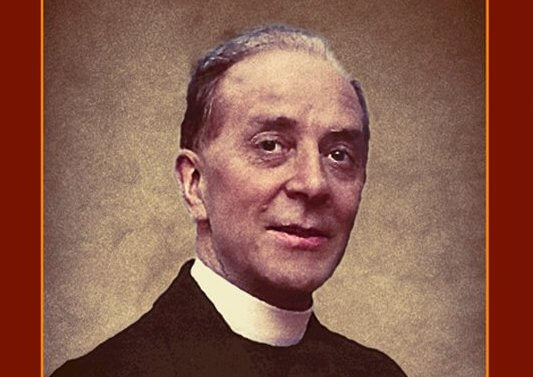

Unwanted Priest: The Autobiography of a Latin Mass Exile

By Bryan Houghton

Angelico Press

Paperback: $16.95 / Hardcover: $26

206 pp

This is a book which anyone interested in the controversies surrounding Vatican II, the Latin Mass, and modernism will find interesting and thought-provoking. Yet it must be recognized as a dated, incomplete, and partial account, defects which simultaneously hinder and augment its usefulness. Perhaps its most important contribution to us today is to give a clearer picture of how hopeless the situation must have seemed for those who loved the Latin Mass even 30 years ago, and how far we have come since then. In the final analysis, however, it is an account which raises questions it does not answer, begs to be placed in perspective with other sources, and needs to be read with more than a few grains of salt.

Unwanted Priest is the autobiography of Bryan Houghton, a British convert to Catholicism. “I do not propose to write my social autobiography—which might be of interest as I have met many people far more interesting than I,” Houghton writes. Rather, this is to be his “religious autobiography.” Born in 1911, in his youth Houghton was educated both in France and England, and brought up more or less Anglican. In 1928 he began to attend Christ Church, Oxford. Here he began to associate with Catholic figures such as Ronald Knox, Sligger Urquhart, and Martin D’Arcy. Yet it was not until several years after he left Oxford that a combination of events, friends, and reading brought him to conversion.

Father Houghton’s book contains many passages of beautiful reflections, almost casual ramblings on the Catholic faith and his experience of it. Charming and witty, they have an anecdotal quality which makes them particularly striking, as if he were treating you to tea in his rectory. Recounting four things he found “divinely attractive” about Catholicism, he describes attending a High Church Anglican service and a Roman Catholic Mass consecutively one Sunday: “the difference between the two ceremonies stood out perfectly clearly. The Anglican service was the memorial of the Passion of Christ in gratitude for our redemption. It was the noblest of human acts, but a human act it remained. The Mass, on the other hand, was a divine act.” It was the distinction a French schoolfellow had made for him when he was a young boy: that “Protestantism is about Jesus, whereas Catholicism is Jesus…”. The “second great attraction” was the “infallible papacy”, a unique and “necessary claim of the True Religion.” Thirdly, Houghton was impressed by the Church’s moral teaching. “I was a young man. Temptation was coming my way, both sexually and in life generally. I needed a firm guiding hand. The Church gave it as nobody else could.” Finally, he was “overwhelmed by the holiness and discipline in a number of Catholic families which I knew.”

“Of course, in the first ardour of conversion and at the age of twenty-three I immediately thought of the priesthood. But at the same age one also thinks of girls.” Houghton describes three: the French girl Francine, respectable and eligible; an English girl who tried to seduce him in Paris; and a remarkable Italian, “but very dominant,” who remained a good friend for many decades. However, after caring for his ailing mother for eighteen months, in 1936 Houghton arranged to enter the Beda college in Rome, founded expressly for English-speaking late vocations.

Father Houghton labored in parishes for almost thirty years. He recounts many anecdotes of his experiences during this time, with everyone from bishops to farmers. However, he also chronicles the events and atmosphere leading up to the Council, pausing the flow of the biography several times to insert theological essays originally published elsewhere. His most notable piece is “Prayer, Grace, & the Liturgy” in which he explores “a problem to which I found an answer difficult. All priests had said the old Mass daily and with due decorum and even with apparent devotion. How came it that ninety-eight percent were perfectly willing to change it—and this not at the behest of the Council or of the Pope? A pure permission was given, and they all jumped to it like the Gadarene swine.” This essay is very intriguing, positing a divide in the theology of prayer which stretches back several hundred years as the source of the modernist muddlement over the role of liturgy in the economy of salvation. He claims that an increasing focus on asceticism, that is, on what we can actively do to exercise virtue and to pray, overshadowed an older emphasis on the primacy of contemplative receptivity in prayer, and that this predisposed the clergy to want a more “active” role in shaping worship. It was a shift from adoration to self-improvement. The activist aspects of the Novus Ordo, then, resonated with common tendencies in the clergy’s spirituality. Conversely, the laity were more accustomed to being “receivers” at Mass, and the changes were therefore more foreign and shocking in many ways.

In 1969, Houghton resigned his position as parish priest in order to avoid saying the Novus Ordo. The Constitution of the new Roman Missal, he says, “simply abolished the Mass and substituted—to start with—four masslets.” With ecclesiastical approval he retired to France, where he continued to celebrate the old Mass for the rest of his days. In this period he recounts meetings with Lefebvre, Dom Gerard Calvet (founder of Le Barroux), and other important figures. His comments on the post-conciliar decades make us realize how much of a revival the Church has experienced in some places since the beginning of the twenty-first century, and particularly since Sumorrum Pontificum.

Many of Houghton’s statements are open to question. They are one man’s version of the story. For example, his portrayal of Lefebvre and the Society of St. Pius X is far from balanced, and gives them very little benefit of the doubt. Summing up the content of the whole book, one gets the impression that Houghton was something of a curmudgeon, highly opinionated and not too concerned about whether or not he offended others with his opinions. Noteworthy examples of this lack of nuance include his comments on Lefebvre, mentioned above; his insufficiently subtle discussion of evolutionary theory; his use of the term “deicide” in discussing the theology of the Mass and Real Presence; and his statement (even if meant to be hyperbolic), while trying to discredit Bremond’s theory of prayer, that if Bremond was right “it would remain a profound mystery how anybody as stupid as the Little Flower or Bernadette Soubirous ever prayed at all.”

Again, Father Houghton’s character is at times seemingly inconsistent. While he clearly conveys sensitivity and empathy towards others in some cases (and especially in certain passages of his beautiful and moving novel Judith’s Marriage), at other times he seems to be remarkably acerbic and uncharitable. A good example is the way he once conducted a non-religious burial for a Communist party leader he had just excommunicated: after delivering a speech to the congregated Communists to the effect that their leader is now burning in hell and that they will too if they don’t repent, he throws stones at the coffin and encourages the rest in attendance to do likewise. All in all, there are a few passages like this one which leave one scratching one’s head and wishing that Houghton had had the benefit of an editor.

These defects make Unwanted Priest hard to recommend as a stand-alone work; rather, it needs to be placed in the context of a library on traditionalism. Despite its enjoyable British humor and vignettes from a highly cultured man who had seen a lot of the world (and of the Church), it is probably not a book for the average layman. Instead it seems to be an important reference work for researchers of the traditionalist movement who have studied a sufficient variety of sources to enable them to weigh and balance its statements against other material. Angelico Press should be thanked for publishing this autobiography in English for the first time (as the manuscript had been lost for decades), and for bringing back into print Fr. Houghton’s other, more polished works, the aforementioned Judith’s Marriage and his satirical novel Mitre and Crook.