The sin of Peter recounted in Matthew 16 — “Then Peter took him, and began to rebuke him, saying, Be it far from thee, Lord: this shall not be unto thee” (v. 22) — is the archetype of papal sins against the Mass.

Note that Peter’s “rebuke” hinges on the avoidance of the Cross. The Mass is the re-presentation of the sacrifice of the Cross; therefore Peter’s attitude, translated into the era of the Holy Spirit, that is, the era stretching from Pentecost until the Second Coming, would be found anew if ever a successor of his tried to resist the demands — moral, ascetical, doctrinal, aesthetic — that the sacramental sacrifice places on us; if he tried to resist the burden of negative and difficult things that must be borne for our own good and that we would ignore or contradict to our harm.

The evangelist continues: “But he turned, and said unto Peter, Get thee behind me, Satan: thou art an offence unto me: for thou savourest not the things that be of God, but those that be of men” (Mt 16:23).

As Roberto de Mattei notes:

The infallibility of the pope does not mean in any way that he enjoys unlimited and arbitrary power in matters of government and teaching. The dogma of infallibility, while it defines a supreme privilege, is fixed in precise boundaries, allowing for infidelity, error, and betrayal. Otherwise in the prayers for the Supreme Pontiff there would be no need to pray “non tradat eum in animam inimicorum eius [that he may not be delivered into the hands of his enemies].” If it were impossible for the pope to cross to the enemy camp, it would not be necessary to pray for it not to happen. The betrayal of Peter is the example of possible infidelity that has loomed over all of the popes through the course of history, and will be so until the end of time. The pope, even if he is the supreme authority on earth, is suspended between the summit of heroic fidelity to his mandate and the abyss of apostasy that is always present. (Love for the Papacy and Filial Resistance to the Pope in the History of the Church, 84)

The word “Satan” means adversary or accuser. By his resistance to Calvary, Peter is setting himself up as an adversary of what Christ came to do and to suffer. A successor of Peter might likewise set himself up as an adversary of what Christ continues to do, above all in the mystery of the Sacrament of His Passion, the Most Holy Eucharist, enshrined within the rite of Mass. Peter is accusing Christ of, in a sense, “going too far” — of letting happen to Him that which is unfitting, or that which will demand of the disciples too much faith or effort.

The liturgy in its full ancient-medieval-Tridentine development realizes in ritual form the kingship of the crucified and glorified Christ, and in order to establish His reign over us, demands much of us: we must deny ourselves, get down on our knees, and pray, in union with the priest who offers the sacrifice on our behalf. We are tempted to resist this form of ecclesial self-discipline, to push against its demands. We are tempted, in other words, to become little “Satans,” stumbling blocks for the Lord’s mission among us, as we savor things human rather than things divine.

What are these human things we savor?

“Thou savourest not the things that be of God” — His liturgical Providence, the Holy Spirit leading us into the fullness of truth in our worship as well as our doctrine — “but those that be of men,” aggiornamento, ressourcement, Nouvelle théologie, “dare we hope,” etc., a range of excuses for bracketing out and burying whole portions of our Christian tradition in order to find a more commodious niche for our modernity, pleasantly tricked out with selectively antiquarian frills.

Put more bluntly, it would seem that ease and comfort are basic givens of the liturgical reform. How so? Well, the rites were expressly designed to be:

- easy to understand (hence, the vernacular, always spoken out loud, with priest facing people),

- with easier postures (hence, less kneeling, and fewer variations during the liturgical year),

- altogether briefer (hence, fewer and shorter prayers, and the multiplication of extraordinary ministers to expedite Communion),

- with fewer difficult, i.e., perplexing, sobering, or severe, Scripture passages (hence, the removal of numerous challenging Bible verses from the lectionary and breviary),

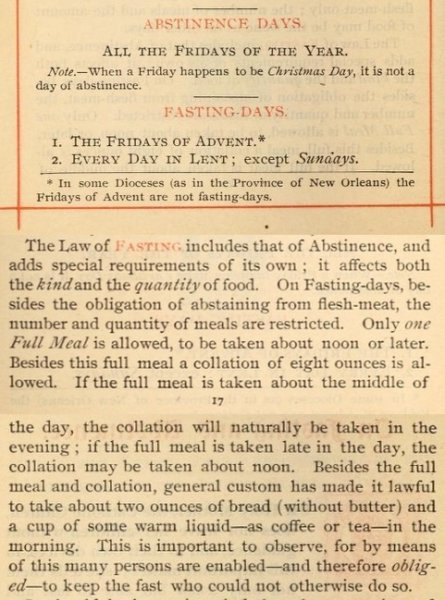

- prepared for by less fasting (one hour instead of three hours or from midnight),

- and with musical styles more familiar and worldly, and less dependent on well-trained musicians.

In comparison with the traditional rites:

- the Mass as a God-pleasing sacrifice is deemphasized, and the aspect of a welcoming fraternal meal dominates;

- the orations are edited to remove or downplay traditional aspects of the Faith: “detachment from earthly goods and the longing for the eternal; the struggle against heresy and schism; the conversion of unbelievers; the necessity of returning to the Catholic Church and to unadulterated truth; merits, miracles, apparitions of the saints; God’s wrath against sin and the possibility of eternal damnation” (these words are from Michael Fiedrowicz);

- the “distance” between priest and people — emphasizing Christ as the only Mediator between God and man — is canceled or relativized by vernacularity, versus populum, the permeable revolving-door sanctuary, etc.;

- the new rite holds us by the hand with scripted responses and actions, promoting spiritual infantilism and never allowing the natural development over time of an interior life supported by devotions;

- the new rite is much less demanding on the priest in terms of complexity of ceremonies and specificity of rubrics.

These are a few of the many ways in which the reformed rites cater to the tendencies of our fallen human nature, which hates discipline, effort, attentiveness, self-denial, meditation, and submission to fixed forms — although Christianized human nature gravitates toward just these things, as an intelligent sick person welcomes the proper remedies for his condition.

Why did it come crashing down?

Today’s skeptics will quickly formulate an objection. You praise the Church’s traditional discipline, but tell me: why did the whole structure come crashing down so quickly in the 1960s and beyond? Surely (the skeptics say), there must have been something wrong with what was there before — some fatal flaw or systemic weakness. It was a house of cards, a termites’ nest, a brittle façade hiding the emptiness of social routine.

Actually, having talked to a lot of older people, I’m convinced that part of the explanation is a lot simpler and less ominous (not that there are not other factors to be taken into account, but that is not my focus here). Fallen human nature loves to get a break from discipline. When people go on vacation, they often “let it all hang out”: they drink lots more beer or wine than usual, eat lots of desserts they normally might shun, binge-watch movies, don’t tuck in their shirts (or maybe don’t wear shirts at all), and so forth. We see this with Catholics who relish Fridays that happen to be “Solemnities” so that they can freely eat meat — which they are eating every other day anyway. Basically, unless we are persons of unusual virtue, we’ll gladly take advantage of any excuse to slack off.

Whatever else it was, the Catholic Church prior to Vatican II was by and large a realm of discipline, order, rules, and requirements — not always consistently followed, but consistently praised and held up, and that is exactly as it should be. Catholicism cannot exist otherwise, any more than a mammal’s body could remain coherent without a skeleton supporting it, or an organism could remain a unity without a soul giving life to it. Yes, the Faith is so much more than this kind of structure, but it is at least this, for which there is no substitute.

Now, if you suddenly tell the entire Church: “Hey, Church, it’s all called off! Lenten fasting and Friday abstinence are gone or optional. You ladies don’t have to wear veils, you nuns can get rid of the many-layered habits. Clergy, you don’t have to study Latin, everything’s in the vernacular now; you don’t have to sweat over detailed rubrics; there aren’t eight parts of the breviary but only five (and each of those is cut way down),” etc., this is basically an announcement that we are all on perpetual vacation from school: it’s permanent recess time.

If you give people a high bar and say “You must clear it,” they will work to clear it, and if they don’t clear it, they will recognize themselves to be slackers and take it to Confession. If you say: “Here’s the low bar and it’s good enough; step right on over it or even walk around it if that makes you feel more like yourself,” how many will train for the high bar? How many, honestly, will even care about the low bar? They will probably just go off to a bar.

The simplest explanation for the postconciliar collapse is that the Church — by this, I mean churchmen, of course, not the Immaculate Bride of Christ who dwells in the heavenly presence of the Most Holy Trinity — simply stopped demanding asceticism as a baseline and excellence as an ideal, and fallen human nature knew how to run with that. Disordered concupiscence whooshed in to fill the abhorrent vacuum. As we know looking to the field of architecture, it takes decades or centuries to build something great, and only a few wrecking balls or bombs to level it down.

C.A. Thompson-Briggs sums up the point: “Comfort is one of the idols of modernity and one of the great enemies of beauty.” The systematic implementation of ease and comfort in the modern liturgy, together with its supporting legislation and environment, reflects and reinforces the modern Western self-centered lifestyle and its relentless excision of beauty as useless and (ironically) self-indulgent. It seems to be based on a final admission that the Enlightenment was right, after all, to define human beings as either purely rational or purely animal (depending on whether one is dealing with the more idealistic strands or the more skeptical and materialistic ones), rather than seeing man as fundamentally an aesthetic being ordered to transcendence through contemplation and subcreation, and therefore as a being urgently in need of the goods of tradition, discipline, order, and challenge in order to realize his humanity, to humanize the world around him, and to lift himself and his world to God as a sacrificial offering on the altar, at the foot of the Cross.

In short: either we savor the things of God that lift us above ourselves, a path that leads to heaven by the paradoxical way of ascesis and beauty; or we savor the things of man fleeing from God — a path that leads downwards in every way, personally and culturally. We know, thanks to St. Matthew, how Our Lord evaluates these alternatives. We know, indeed, that St. Peter exemplifies both in succession, and so do his successors, in varying degrees and ways.

Photo credit: Unsplash.