|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

“Happy Easter”, we still say 7-day week afterward because, liturgically speaking, it has still been Easter Sunday during this Octave. A liturgical Octave is an eight-day arc that vibrates in anticipation of the “eighth day” of eternal rest beyond the 7-day cycle of creation. We stop the liturgical clock so that we can rest in the mystery of the Resurrection. This allows us to contemplate it from different angles, especially using the Office and Mass formulas each day. If you are confused about how we get eight days from Sunday to the next Sunday, the counting of the days is inclusive. By inclusive counting, Easter Sunday is 1, Monday 2, etc., so that the next Sunday is the eighth day. This is an ancient way of counting used by the Romans and other cultures. We have a parallel in music, whereby an octave has seven intervals between the notes: go up seven notes and that’s the octave. In Rome, where I write this, if I want to express a two-week period, an English “fortnight” (fourteen nights), I say “quindicina” (a grouping of 15). This is an example of inclusive counting. But enough about that.

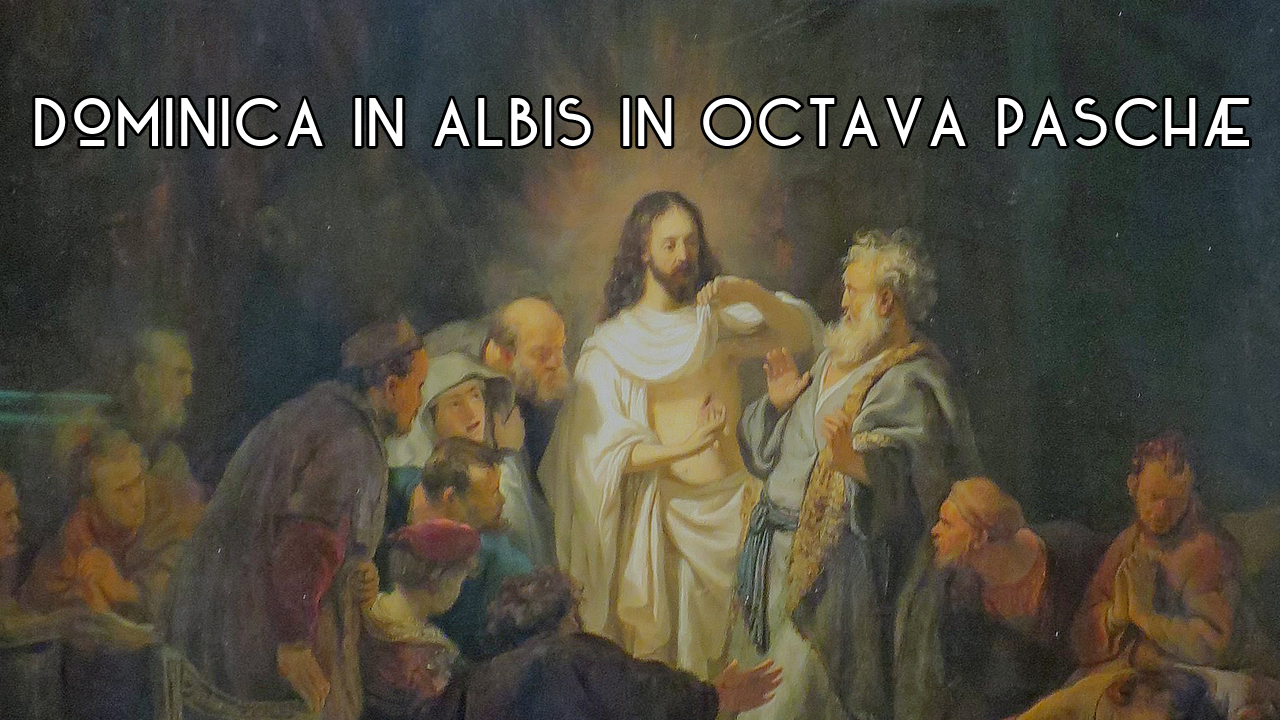

Numerically, most of the Catholic world will be celebrating Divine Mercy Sunday on this Octave of Easter. Historically, this Sunday is called Dominica “in albis” or “in albis depositis”. On this day in the ancient Church, the newly baptized, or infantes, finally put off (“de-pos-“) their white (“alb-“) baptismal garments. Hence, it is also called Quasimodo Sunday, because of the first word of the Introit chant from 1 Peter 2:2-3 in a Latin version more ancient than the Vulgate of St. Jerome (+420), thus giving a name also to Victor Hugo’s “hunchback” of Notre-Dame, a foundling discovered on this Sunday. Here’s the verse. In the translation I’ll include the immediately preceding verse, which thematically ties together this Sunday with Easter.

2 Quasimodo geniti infantes, rationabile, sine dolo lac concupiscite ut in eo crescatis in salutem si gustastis quoniam dulcis Dominus. … [1 So put away all malice and all guile and insincerity and envy and all slander.] 2 Like newborn babes, long for the pure spiritual milk, that by it you may grow up to salvation; 3 for you have tasted the kindness of the Lord.

Last week, for Easter Sunday, the first reading had us putting away “leaven”.

“Let us, therefore, celebrate the festival, not with the old leaven, the leaven of malice and evil, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth” 1 Cor 5: 8).

There is a thematic connection between the two Sundays not just in the matter of celebration of the Resurrection, but also in the way we must treat each other. The “victory which has overcome the world” brings moral implications. Our ancient predecessors in the Faith lived cheek by jowl with pagans in a still heavily pagan world. The need to impress Christian virtues and behavior on the newly baptized was a matter of existential importance in Christian communities, even after the major persecutions were ended. Can we draw any conclusions from their experience for our own day, increasingly pagan as it is? Our comportment should not be conformed to the world, as Paul says in Romans 12:12:

Do not be conformed to this world but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that you may prove what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.

Yet we read survey after survey that says that Catholics pretty much conform to the folly of this world in numbers on par with non-Christians. What does that tell us? I believe it has to do with the way we have been praying collectively as a Church for the last few decades. Draw your own conclusions from that.

Given that so many of our brethren with the Novus Ordo are observing what John Paul II, due to his devotion to the writings of the Polish St. Faustina Kowalska, determined to call Divine Mercy Sunday, let’s delve into Christ’s great mercy manifested on this Octave Day.

The Gospel reading is from John 20:19-31. We need context. John 20 begins with the Resurrection and Mary Magdalene reporting to the Apostles. They dash to the empty tomb (vv.1-10). Jesus appears to Mary and, getting her steps in, she returns with that news to the disciples (vv. 11-18). So, we arrive at the Gospel pericope (a cutting of scripture for liturgical reading). We have arrived in the Gospel account at the “evening of the first day” (v. 19), hence the evening of Easter Sunday. Though the Apostle Thomas is not present, the Lord appears to the disciples in the closed room. He “sends” them, and He breathes on them saying,

“Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.”

Stop here and contemplate what that means. Christ’s “sent ones”, the Apostles and their successors and their collaborators sharing in Christ’s ordained priesthood, can forgive sins. They can forgive sins. Christ didn’t say, “whose little, inconsequential sins you forgive…”. He didn’t say, “the sins of only a certain class of people…”. No one is so lowly or reduced that they are excluded from God’s Mercy. No sin is so great that it cannot be forgiven. But how are sins to be forgiven if they are not known to the one who has the power to forgive or to retain? To forgive or retain, a judgment must be made about the sin. Therefore, the sin and its attendant circumstances must be known to the minister of Christ’s forgiveness. Consequently, the sin must be told to the confessor.

On the evening of that first Easter Sunday Christ instituted the Sacrament of Penance, of Reconciliation.

After baptism, if and when we fall and sin, we are not forever struck off the list of the saved. We have a way back to Christ in the Sacrament of Penance.

It is precisely through this sacrament that God wills for people to obtain forgiveness for post-baptismal sins. It is God’s will that we return to Him through sacramental confession. That’s why He instituted the sacrament.

In the second part of the Gospel, we have the famous scene with the “doubting” Apostle Thomas, who was absent on the evening of Easter Sunday. We don’t know why Thomas wasn’t with the other ten remaining Apostles in the room for that first appearance of the Lord. I like to think that it was his turn to get the “take out” for the rest of them. Christ could have waited for all the Apostles to be together the first time He appeared. But He didn’t. There must have been a purpose behind that choice.

The first part of the Gospel reading concludes with Thomas’ expressions of disbelief about Christ’s appearance. In this next part we are “eight days later”, the Octave, that is the Sunday after Easter Sunday. The Lord appeared suddenly in their midst and said, “Peace be with you”. When the Lord, the Eternal Word, said “Peace be with you”, He was both talking about Himself being present, but He also was transforming their lives through His invocation. This same greeting is used in Latin by successors of the Apostles, bishops, when they celebrate Mass. Whereas a simple priest says “Dominus vobiscum!”, the bishop says “Pax vobis!”

In His first appearance on Easter evening, Christ showed the disciples – but not the absent Thomas – His hands and feet and side, to demonstrate that He had a real body and that it was also is His Body. He didn’t pick up some unwounded, perfect Body that He was now inhabiting. We are our bodies, as we are our rites. The fact that the wounds remained in His Body’s hands, feet and side provided continuity with His Body before and during His Passion. He didn’t exchange Himself for a new, unwounded version. In this way Christ began to show them the traits of the risen Body, traits which we, too, will share in the Resurrection: clarity (reflecting God’s glory), impassibility (incapable of suffering), agility (ease and speed of movement), subtlety (unhindered by barriers).

Thomas, who had doubted, put his trust in the Lord at this point. Christ told Thomas to explore with his finger (dáktylos) the spike holes of His “hands/wrists”, which would be the size of a large finger. The Greek word “cheír” can mean “hand”, but it can also mean “finger” or “hand and arm”, the later so much so that in some contexts additional words are added to denote “hand” as distinct from the arm (cf. Liddell-Scott-Jones, A Greek-English Lexicon aka LSJ – “χείρ , ἡ”). Christ would have been crucified with nails through the wrists so that the ulna and radius bones would sustain His Body’s weight rather than tearing through the flesh of His hands.

The Lord told Thomas to “thrust” (Greek balle) his hand/wrist/arm “eis ten pleurán… into (His) side”, which had been opened with a “lance” or “spear”, in Greek lónche. It is hard to know exactly what kind of spear this was, a pilum with a narrower point, or the lancea with the broader leaf-shaped blade. The relic of the spear of Longinus, thought to be the very spear, has the latter, the larger point. The pilum, a common javelin-like spear for foot soldiers, had a narrower point but it was often barbed, so that it would stick where it was thrown. That means that it would tear a large hole in flesh as it was pulled out. The bottom line is that the hole in Christ’s size was big enough for Thomas’ cheír, his forearm.

Here is when Thomas literally handed his trust to Jesus.

Christ told Thomas to explore he spike holes with his finger. He told him to use his hand for the wound in His side. The Greek suggests that the Lord instructed Thomas to thrust (Greek balle) His hand, even his wrist and forearm, into the wound channel left by the spear, which had gone in far enough to lacerate the Lord’s Sacred Heart.

We don’t have in the Gospel account of this moment, to which John was eyewitness, an explicit statement that Thomas physically did these things. However, when the Risen Christ tells you to do something, you do it.

Thomas made His exclamation of faith, “My Lord and my God!”

John immediately concludes this chapter with something so definitive that it feels like the end of the whole work (vv. 30-31):

Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of the disciples, which are not written in this book; but these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name.

Just looking at Christ or just touching Him doesn’t seem quite enough to provoke Thomas’ cry or John’s dramatic words.

One has the sense that what happened between Christ and Thomas was so amazing that John penned something like a conclusion to his Gospel after Thomas’s cry of faith, arguably the climax of John’s account.

This is where I venture into informed speculation. Firstly, Thomas was not with the other Apostles on that first Easter Sunday when Christ breathed on them. However, the breathing was essential and tied to the Holy Spirit. Next, consider the meanings of “hand” in Greek, including the wrist. Also, Christ said “thrust” (rather like a spear). Moreover, the wound from the lance remained in Christ and therefore remained all the way into His Heart.

I believe Our Lord required Thomas not merely to touch His side but thrust his hand all the way to His Sacred Heart, to receive His breath, the ruach, from within His torn lung. I think this how Christ at last “breathed” on Thomas.

I then ask myself, did Thomas, while feeling the ruach on his wrist, touch with his hand the physical, risen, subtle, impassible, agile, blazing bright Heart of Jesus?

In the Sacrament of Penance, Christ’s breath touches you. His blazing bright Heart beats for you.

On this Sunday we emphasize the mercy of God and the institution of the Sacrament of Penance, perhaps the greatest encounter we have with incarnate Mercy, Holy Communion notwithstanding.

Christ told Thomas to do what He did before witnesses so that they too would understand about the traits of His risen Body and that it was truly His own. Knowing full well that we would one day read this, He inspired the disciple He most loved to write his Gospel account, an account that connects Thomas to the inspiration of the Spirit and the mercy of Christ’s Heart in a way that other Apostles didn’t experience on that first Easter evening appearance. Mercy upon mercy abounding.

God’s Justice we will receive whether we want it or not. But His Mercy is ours for the asking.