One of the many encouraging signs in the Traditionalist ‘movement’ today is the growing understanding that the contemporary crisis in the Catholic Church does not simply originate in the neo-Modernist recrudescence of the 1940s to the 1960s, nor in the original Modernist wave of the 1900s that St Pius X fought against, but in fact has a plethora of deeper roots reaching back even to the disputes between rival religious scholastics in the late-Middle Ages. I mark this recognition as part of the maturation of Catholic Traditionalism that is to be welcomed and fostered.

An increasing number of traditionalist scholars are critiquing the ‘manualist tradition’ of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries as inadequately fulfilling the wishes of Pope Leo XIII’s call in Aeterni Patris to revive the philosophy of St Thomas Aquinas. This is a complex and thorny issue, so without going into too much detail I will provide a brief summary: after Pope Leo’s encyclical Aeterni Patris, St Thomas’ works were often judged to be too dense and complex by many seminary teachers, and so students would instead read neo-scholastic commentaries, or ‘manuals,’ on St Thomas’ thought, that were characterized by concise formulae that tended to abstract the richness of his thought away from its Biblical and patristic sources. Manuals indeed played an important role in distilling various aspects of the faith in a concise manner – not unlike the aims of St Thomas’ Summa. Yet an excessive use of manuals resulted in a theology and philosophy was that was rather dry, and seemingly removed from its origins, ending up looking something like what Dr Sebastian Morello has called ‘Russian-doll Thomism,’ with commentaries being made of commentaries being made of commentaries, and St Thomas’ original florescence being somewhat diminished as a result.

Lest the reader think I am merely parroting the talking points of Bishop Robert Barron, the greatest Thomist of the era (and indeed the whole twentieth century) stated at the beginning of his magnum opus on the spiritual life that he was choosing against using a manual for his subject. Why? Because, he said, “great risk is run of being superficial in materially classifying things and in substituting an artificial mechanism for the profound dynamism of the life of grace.”[1]

The unfortunate reaction to this ‘manualism’ – which has been defined as ‘Apatristic Scholasticism’ – was the Nouvelle théologie and the call for a ‘return to the sources’ (ressourcement), which seemed to have been so obscured. This current then became infected with the ideas of the heresy of Modernism via the confluence with such poisonous streams as the German biblical ‘historical-critical method,’ and the rest, as they say, is history.

The Dialogos Institute is a theological institute founded in 2015 to help remedy this disaster by recovering the patristic heritage of the Church in the spirit of faithful Latin and Byzantine Thomism. Many Catholics are unaware of the rich tradition of ‘Byzantine Thomism’ that budded in the two centuries prior to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, and was critical to the successful, though short-lived, Union of Florence, healing the schism between East and West, in 1439. Byzantine Thomism was characterized by a fruitful cross-pollination of St Thomas’ thought with the Greek Fathers, to the extent that one of the Dialogos Institute’s founders – Dr Alan Fimiser (co-author of Integralism: A Manual of Political Philosophy) – has called it the true fulfilment of Eastern Christian theology and one lung of ‘Bi-pulmonary Thomism.’ The Dialogos Institute’s important mission is, therefore, to help recover the tradition of Byzantine Thomism, and thus help ‘restore the collapsed lung’ of the Church in the East.

When Pope Innocent III heard about the sack of Constantinople by the Venetians and Crusaders in 1204, he was both incensed and grieved over the great crime. With time however, he came to see, that God may be affecting the good of reconciliation of East and West through the catastrophic evil of the sack. The Latin conquest coincided with the foundation of the mendicant orders and the friars would henceforth go on to play a predominant role in the religious life of Latin Christians in the East.

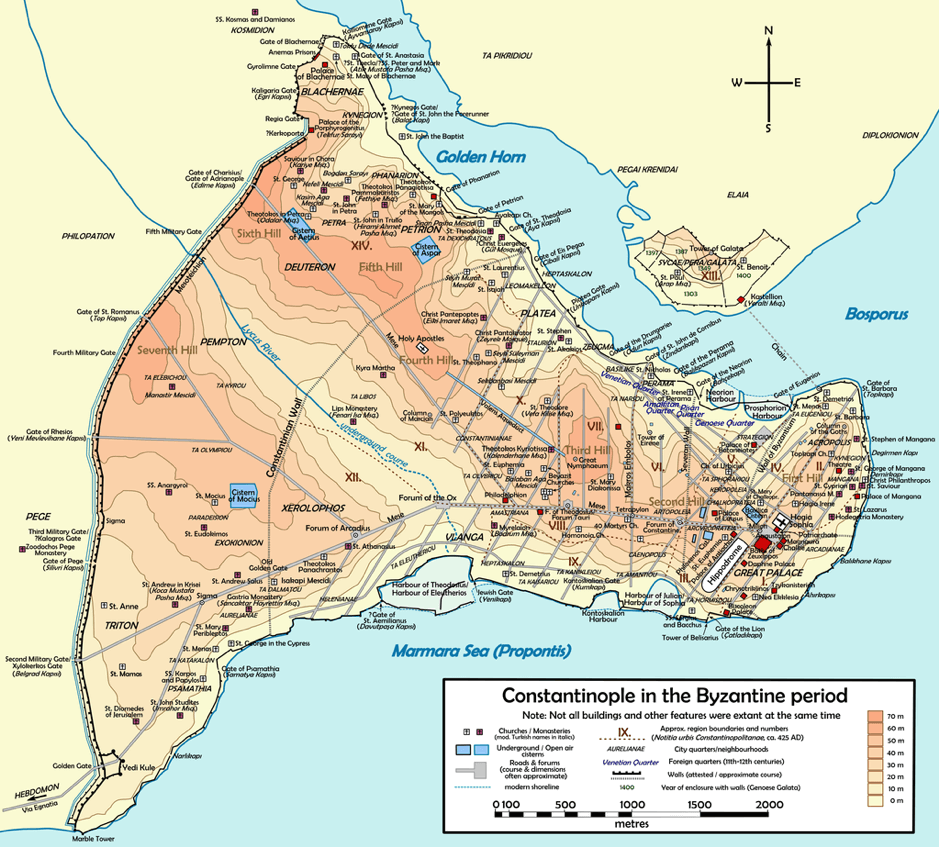

The first representatives of the Dominican Order arrived in Constantinople in 1232 and eventually established themselves not only in the city itself, but also, under the aegis of the Republic of Genoa, in the colony and citadel of Galata, northwards, across the water of the Golden Horn.

Despite the Byzantine recapture of Constantinople from the Latins in 1261, for the next two hundred years the Catholic Community flourished here in Galata, with numerous churches, convents, friaries and monasteries built. Through the Dominican Studium generale, Galata also became the conduit for the transmission of the thought of St Thomas Aquinas, and Scholasticism generally, to the East.

The man responsible for the translation of both the Summa contra gentiles and the Summa theologica from Latin into Greek was the noble-born Byzantine scholar Demetrios Kydones in the 1350s, who remarked that St Thomas knew Plato and Aristotle better than the Greeks themselves. He would go on to translate some of the works of St Augustine, St Anselm and other Latin writers. Kydones’ detailed study of Latin theology informed his criticism of the Palamite doctrine, and by 1365, he made a profession of faith in the Catholic Church. Appreciating St Thomas’ application of apodictic syllogisms to theology, Kydones saw a way of avoiding what he regarded as the pantheistic implications of Hesychasm. For him, reasoning and the use of syllogisms lay in the very essence of man. Kydones followed Thomas’ notion of Divine Simplicity to reject the distinction between God’s essence and energies, made by the Greeks of the Hesychast school, thus incurring the enmity of the followers of Gregory Palamas. Demetrios Kydones became Imperial Prime Minister under three emperors and rigorously advocated for re-union with the Latin Church. This movement for re-union was subsequently propelled by the Byzantine Thomist school, as well as by political considerations for the defense of Christendom against the rising Mohammedan Ottoman power. The Byzantines were also particularly impressed by the apologetic skills of Aquinas, which they put in the service of their own disputes with Mohammedanism.

As a result of this dynamic dialogue between the Byzantines and the Latins, even those who opposed reunion came to appreciate the greatness of the Angelic Doctor. Ultimately, Aquinas’s reputation reached a pitch in Byzantium, before the tragedy of 1453, that it would not attain in the west until the late nineteenth century. Paradoxically, St Thomas Aquinas’ high reputation in Byzantium coincided with a low point in his reputation in Latin Christendom, partly because of the tragic rivalry between the different religious orders. By the time of Martin Luther, the Summa does not seem to have been widely read at all – again, the perception about St Thomas’ thought was largely formed by commentaries.

The Byzantine reception of Thomism bore fruit in the great reunion Council of Florence (1431–1445) under Pope Eugenius IV, where the seven hundred Byzantine delegates led by Patriarch Joseph II and Emperor John VIII accomplished the reunion of the Churches. Notably, Pope Eugenius and the Council sided against the Dominicans on the question of Palamism, and refused to dogmatize either the Thomistic conception of the Filioque, or the Thomistic rejection of Palamism. Instead, the Council sided with the Scotist Franciscans which allowed the reunion to be completed. (Nevertheless, to this day many Greek Orthodox misunderstand this dogmatic fact and on that basis refuse reunion with Elder Rome.)[2] But because of the great seeds which had blossomed in the east through Byzantine Thomism, ultimately the great bull of reunion Laetentur Coeli was proclaimed in the presence of Pope and Emperor from the Duomo in Florence.

The Dialogos Institute’s work is to reap the harvest of the liturgical, spiritual and intellectual heritage of both Old and New Rome, and offers several tantalizing opportunities. For instance, Church life today is marked by almost a complete loss of the the perception of the Sensus Fidelium, which so guided the Church in the Patristic age. One wonders what St John Henry Newman would say about the suppression of one of the only parts of the Church faithful to Her teaching by the Supreme Pontiff (Traditionis Custodes). Indeed, a true ‘return to the sources’ of the faith through the Socratic method of disputation (the Socratic dialogos, “dialogue”), might help remedy the hyperpapalism, identified by Dr Peter Kwasnieski and many others – by adumbrating moral limits on Universal Ordinary Jurisdiction – which has wrought so much damage to the Church in the last century.

The Dialogos Institute pursues these aims through conferences, publications and programmes of study illustrating the unity of the Church’s traditions eastern and western, patristic and scholastic, clerical and lay. Ultimately the true fruit of Catholic renewal is to be found in a renewed sense of the Greco-Roman heritage, that Romanitas out of which God providentially built Christendom. Until the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Greeks called themselves Romans and were under a true Roman Emperor, that last of whom, Constantine XI, died as a Greek Catholic in union with the Pope, heroically defending New Rome against the Muhammadans. Thus did Demetrios Kydones put it:

What closer allies have the Romans than the Romans?

– Demetrios Kydones

[1] Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, Three Ages of the Interior Life, trans. Sr. M. Timothea Doyle (B. Herder Book: 1947), v.

[2] On this see, see the work of Greek Catholic scholar Fr. Christiaan Kappes on Scotism and Palamism.