With the release of another predictably vapid World Youth Day “hymn”, the time may be ripe to once again address the problem of “kitsch” in the Catholic Church. The age of glowing artifice has successfully blinded even some of the most faithful, and it’s high time that somebody shot the elephant in the room (poaching laws be damned.)

Kitsch, as an affront to the Magisterium and a mass stupefying phenomenon, acts as a direct impediment to the New Evangelization. It has the power – like the worst of popular culture – to flatten our sensibilities to authentic beauty, downplay sacred tradition, and get non-believers to roll their eyes “knowingly” at what they rightfully perceive as a tasteless aping of their own shining pop icons.

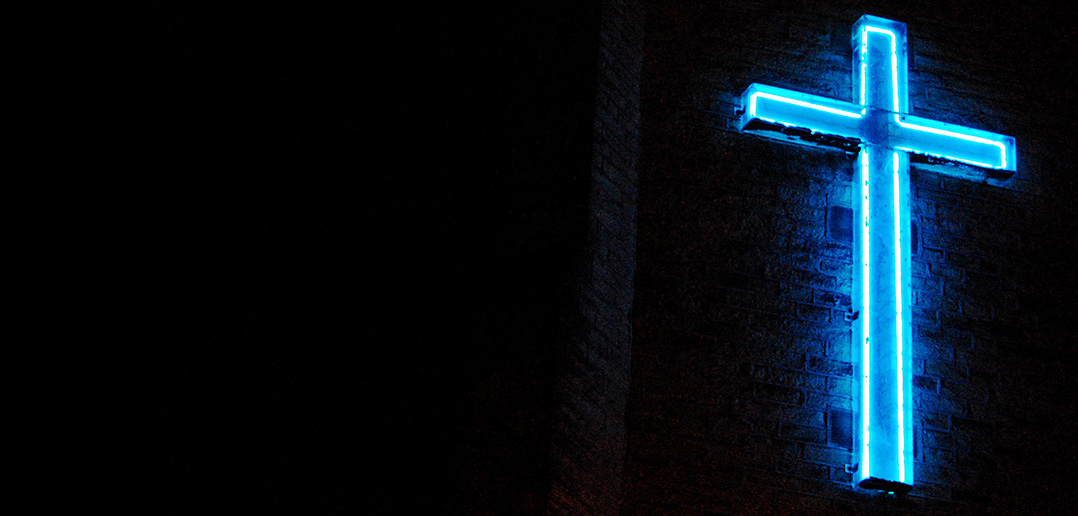

Yet to those fortunate enough not to spend their waking hours thinking about aesthetics and their relationship to theology (or in some cases, losing sleep over it), the question naturally arises: “what exactly is kitsch?” Almost omnipresent in Church life, it is that framed rug wall hanging of the Last Supper, the neon bright saint statue, the “hardcore” Catholic rappers, or a Marian film where the saccharine dialogue reminds one more of an idealized rural Kansas than that of grimy ancient Palestine. It can also come in less obvious forms, like that awful EWTN rendition of the Chaplet of Divine Mercy which sounds like a musical derivative of an awkward high school dance as opposed to a recitation of one of the manliest prayers in the Church.

Kitsch is sentiment over substance; pandering over courageous authenticity.

In a very real sense, kitsch represents a massive crisis not only of Christian taste, but Christian confidence. In Roger Scrutton’s short, sublime, and supremely useful Beauty: A Very Short Introduction,” the aesthetic philosopher writes that:

“Kitsch is a mould that settles over the entire works of a living culture, when people prefer the sensuous trappings of belief to the thing truly believed in. …kitsch is not, in the first instance, an artistic phenomenon, but a disease of faith. Kitsch begins in doctrine and ideology and spreads from there to infect the entire world of culture. The Disneyfication of art is simply one aspect of the Disneyfication of fatih – and both involve a profanation of our highest values. Kitsch, the case of Disney remind us, is not an excess of feeling but a deficiency. The world of kitsch is in certain measure a heartless world, in which emotion is directed away from its proper target towards sugary stereotypes…” (p. 159. Emphasis from this author.)

We can line up this brutal overview next to the powerful words of Cardinal Ratzinger, who spoke of great artistic works as a partner to red martyrdom, acting as the chief witnesses of the faith. In speaking of hearing a concert of Bach with a Lutheran friend, he spoke of how clearly the work evinced a sense of the eternal truths upon which it was based. The advent of such great works may be rare, but they are all (knowingly or unknowingly) based on the same foundation which leads a person to die for their faith. In fact given the supreme mastery and truth-certainness of some artworks, there would doubtless be found countless secular thinkers who would sooner die than see one of them damaged or profaned. At the very least, even if a great work is met with uneducated or unfeeling indifference, it will not meet with the telling eye-roll so often inspired by religious kitsch.

Part of this “spiritual disease” arises from a misunderstanding of quality. Christians are apt to think that if they merely produce a “Christian work” of some sort that its Christian-centeredness somehow makes it sufficient. This is the root of so many tragically bad attempts to present some of the most endearing and enduring stories of our tradition, straight down to the Passion and Death of our Lord Jesus Christ. As a first maxim to avoid making kitsch or bad Christian art in general, we must commit to the idea that just putting the name of Christ into something sub-par does not automatically bestow it with quality. A powerful recent example may be found in film: the reason a rare Christian work such as Mel Gibson’s “Passion of the Christ” was so successful (and actually did bring about mass conversions) – as opposed to countless other homespun efforts which wallow in justified anonymity – is because the director (despite his personal faults) understood that quality had to precede the Gospel message, in much the same way a parent will lovingly make their newborn’s bed before they lay them in it. The filmmaker brought the full force of his craft to the central story of history, and brought with him artists of the highest caliber to bring it to life. Whether or not you quibble with the violence of the film, the final result is a moving icon through which truth speaks – nay, screams in heavenly exultation – to all who behold it. Nor does artistic vision or license interfere with meaning at any point. Only such selfless (and informed) devotion can explain why a film intentionally blacklisted with the full force of Hollywood’s elite machine nonetheless became one of the greatest success stories in cinematic history.

Nor need this be an isolated phenomenon: if we embrace “quality first” as a mantra, and necessarily with it the accompanying fact that Christian art is not a matter for untrained amateurs, we can repeat such successes again and again. We need merely excise the presence of pink wax Padre Pio figures and their equivalents, and embrace the hard but beautifully pregnant possibility of our magisterial legacy.

Idealistic talk aside, how can we do this pragmatically? One way to avoid kitsch and similar aesthetic pitfalls is to label as suspect any talk about “finding the kids where they are,” or “trying something new and fresh.” Such suggestions most often come from those with no real acquaintance with the Church’s aesthetic magisterium, let alone those possessing the intellectual orientation (or humility) to ask advice of somebody who possesses the requisite knowledge and skill (as countless parish “refurbishing” projects can attest to). For every such conversation taking place about “relevance”, somewhere a group of teenagers is kneeling before the Eucharist and learning to sing the Te Deum, proving false the notions of those who would pander down to them.

We should listen to what they have to say.

Certainly, somewhere there is a grandmother whose home is a shrine to kitsch, and who loves her Lord, would die for Him, and is most certainly paving the way to heaven for the rest of us with her ceaseless prayers. Yet such examples – let alone any individual “liking” of bad religious art and Catholic kitsch – is an insufficient argument for the mass production of it or for its general consumption. And it is certainly in the modern means of “mass production” where kitsch has found its surest friend, even though such things are rendered even more unnecessary by the nearly instant availability of quality in the information age.

At its worst, kitsch has a “preaching to the choir” effect which can hobble the efficient transmission of truth. If we are to “run the race to win,” then it makes no sense to purposefully trip straight out of the gate. Where kitsch takes center stage, the world is right to look on in bemusement, wondering what has possibly gotten into our poor “religiously addled” heads. That is because in the world, even the worst tripe is polished and presented with gleaming perfection. The devil burnishes his messages with care, while those who serve God have grown far too careless with their distribution of the antidote.

Or, in other words, the “shining city on a hill” is not a place made out of neon lights where “We are One Body” plays on repeat. Nor can the presence of good intent make these figurative neon lights shine any brighter.

Imagine now a World Youth Day where instead of some pop-derivatives, a million Catholic youth fell to their knees and lovingly chanted the traditional Chaplet of Divine Mercy, after which they would sing and recite the traditional prayers of the Church during Mass. Imagine that metaphorical Te Deum writ large, from millions of souls at once, as a powerful counter-witness to the soul-flattening culture we are all surrounded with.

It would be at this point that eyes would cease to roll, and more souls begin to take notice of the sublime and eternal truth.