In a recent article in Homiletic & Pastoral Review, some odd questions are raised about the use of liturgical Latin:

Is it possible that the Traditional Latin Mass, though beautiful sounding Latin, merely makes one feel good, but lacks the intent necessary for the words to be properly labeled as communication of love of God? Or do all of the congregants have sufficient knowledge of Latin to intend the meaning of the words agreed to or spoken? Can the words uttered in the Latin Mass, although uttered in an angelic tongue, merely be a “resounding gong or clanging cymbal”? What about the potential invalidation of a sacrament (no Eucharist) resulting from mispronunciation of an unfamiliar language? Undoubtedly the questions may cause some heated reactions, but they are only intended to safeguard and ensure the sacraments have their intended effect, especially since there is an increasing use of an unfamiliar language for the sacrament that is the source, center, and summit of the Catholic Faith—the Most Holy Eucharist.

At Liturgy Guy, 1P5 contributor Brian Williams responds:

The obvious response is that for over a millennium, the Roman Mass has been offered in Latin, long after it ceased to be the language of the people. Did this question never occur to anyone before now? Or before the 20th century?

The main thrust of the article seems to be that it is difficult, if not impossible, to pray in a language that is not one’s own. Therefore, the individual worshipper cannot actually intend the meaning of the words, and the Mass cannot be a communication of love of God.

However, this objection misses two very important realities. When the Catechism says that the Mass is the preeminent prayer of the Church, it doesn’t mean “prayer” as a purely individual, subjective, devotional experience, but WORSHIP, that is offered publicly, corporately, and objectively, the ideal worship that is pleasing to God. This is worship as has been established by the Church, under the influence of the Holy Spirit, taking into account both the human experience of religion, as well being faithful to the new reality that has now entered and embraced the human condition, that is the wedding of the human and divine in the God-Man, Jesus Christ, His Incarnation, his life, and His saving Death, Resurrection and Ascension.

Secondly: the Mass is preeminently the prayer of Christ, the offering of the Son to the Father, in which we worship and adore the Son, and join in his offering to the Father. It is not, first and foremost, our prayer. It is Christ’s prayer. It is the heavenly liturgy, into which we are privileged to take part.

A friend of mine posted her own take on the issue on Facebook. I found her thoughts to be unique and compelling, inasmuch as they should be obvious to all of us when considering this issue:

Latin? But I don’t know Latin? That makes no sense. I like knowing what’s being said and what I am saying.

Both my mom and sister are ESL teachers. My mom specifically works with the immigrant population. These are people who come here from all over the world and come to her classes to learn English (the language of our land). It’s hard. Really hard. Some of these folks have little formal education in their own native tongue. But they persevere. Why? Because they want to be citizens of this great country. I find that very ennobling.

I’ve had the great privilege to meet and speak with some of my mom’s students. She’d invite them to our home for dinners or for holidays to celebrate with us. On these occasions they would sit there at our table and do their best to talk with us. They’d struggle to find the right words or to pronounce things just right. But we’d help them out. I was very aware that they must have felt a little awkward and out of sorts. But this just endeared them to me all the more! I couldn’t help being in awe of how they willingly struggled so that they could become a part of a new country. Such dignity and strength!

And so enter Latin. The ancient universal language of the Church. Do I speak, read, or understand Latin? No. Very few do. But it has always been the Church’s “language of the land”. So I too am a poor immigrant pilgrim. I am welcomed and wanted, but there are demands put on me. It’s difficult. It can make me feel awkward or out of place if I let my insecurities get the best of me. But mostly it bestows a great dignity and nobility upon me. I am sacrificing certain familiar comforts for the sake of becoming a part of something higher, something greater. I want to be a citizen of the Kingdom of God. So for those of you who might find yourself a little frustrated by the newer American “press one for English” practice. You think to yourself “hey it used to be that immigrants wanted to and submitted themselves to the learning of English. If you love the United States then just learn the language please!” Consider as Catholics part of the Church Universal we are called to the same heroic struggle. And it’s a beautiful thing. A struggle that ennobles and exalts while it unifies.

[…]

The writer [of the Homiletic & Pastoral Review article] finally uses the spousal relationship to illustrate how important using a common familiar language is for communicating love effectively.

Stunning – his blindness to the certainty that the most intimate and profound communications of love and dedication between spouses come without the use of any words at all! It is in the secret language spoken in silence known only to husband and wife that the mysteries of their love are communicated one to another. Words? Words seem cheap in comparison to this mystery.

This reality is precisely why the Latin Mass effects those who open themselves up to its beauty and demands so profoundly. It’s why they can’t stop talking about it or sharing it. They’re in love! And hearing words in their common tongue has nothing to do with it. Being able to speak words familiar and routine, ordinary and everyday, might make one feel more at ease but it unintentionally cheapens their meaning at the same time.

The resistance to Latin and the Latin Mass seems to me to stem from a need for comfort and a rejection of mystery. Familiar – comfortable.

Mysterious – uncomfortable.

Why does the familiar make one comfortable? Because it’s ours. It belongs to us. We are in control of it. The familiar answers to us. In contrast the mysterious can be scary. When placed into mystery We must ask it “what do you want from me?” We answer to it and its demands.

Sounds a lot closer to the kingdom Jesus described to Pilate: “my Kingdom is not of this world”

For most people of common sense, it stands to reason that when moving to a foreign country, we need to learn the language. To expect them to master our own tongue and communicate with us directly is, not to put too fine a point on it, pretty narcissistic.

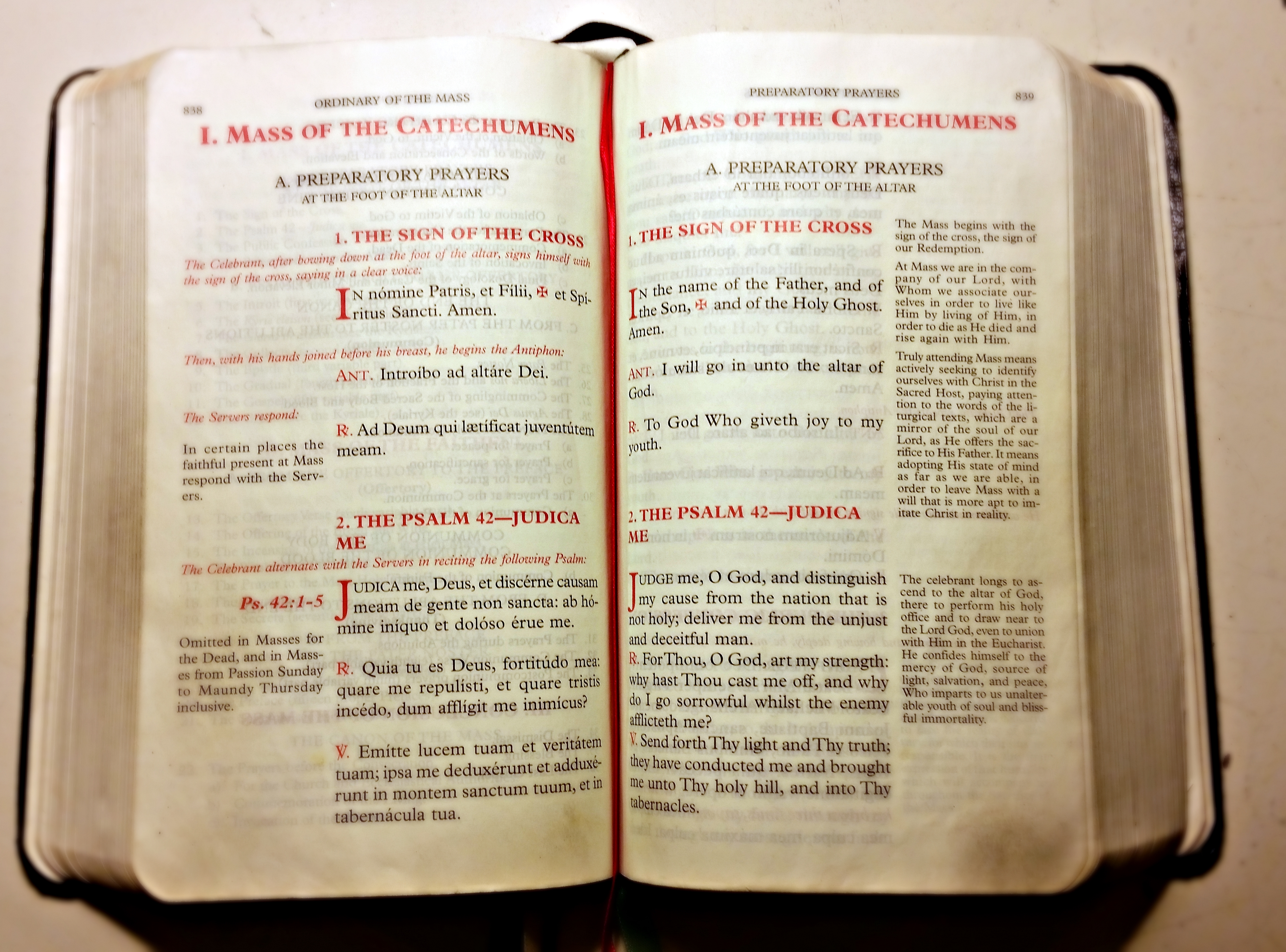

Latin is and for many centuries has been the Church’s living, universal language. I’ve covered some of this history here. I’ve also talked about the ease with which even a person who lacks a facility with Latin can get up to speed and follow a Latin Mass.

Why do we reject ecclesiastical Latin? Why do we, at a time when most people are more literate and thus more educated than they’ve ever been, when we have access to the sum total of human knowledge on devices we can fit in our pockets, do we balk at Latin in the liturgy? Is it really so hard?

Questions like those being raised in Homiletic & Pastoral Review should have long-since been put to rest.

“Why do we reject ecclesiastical Latin? Why do we, at a time when most people are more literate and thus more educated than they’ve ever been, when we have access to the sum total of human knowledge on devices we can fit in our pockets, do we balk at Latin in the liturgy? Is it really so hard?”

Perhaps the answer lies in the prevailing ethos of Western society, namely, that it’s all, for lack of a better term, about me. If I personally cannot understand what the priest is saying, then, clearly to the modern mind, something is horribly amiss. If it might actually require work and effort for me to make sense of what is being said at Mass, well, that’s far too much to expect from the average man in the pew in our world of total convenience in which virtually anything we desire is available at our fingertips whenever we desire them.

To submit to the use of Latin—or any non-vernacular language—in the Mass is to acknowledge that maybe, just maybe, we individually do not know nearly as much as we like to think we do, and that perhaps the world does not revolve entirely around us and our trivial human concerns. Perhaps, in some ways, we are actually less learned than the so-called “simple” peasants who assisted at Mass centuries ago, unable to understand the words being spoken yet instinctively knowing in a more profound sense just what happens at the Holy Sacrifice.

Because faith comes from HEARING, not from READING A TRANSLATION , while HEARING SOMETHING ELSE, which divides the attention, and because we should be in an RECEPTIVE listening,.

Interesting that you make that point when, after having the Mass in the vernacular for more than 45 years, faith in the Real Presence has never been lower in the U.S.

Faith is more than just hearing and understanding words. We also learn by watching the actions of the priest in the sanctuary. In the traditional Mass, it is perfectly obvious to even the most theologically-ignorant layman that something supernatural happens at the consecration, as manifested by the multiple signs of the cross, the genuflections, the care not to let a single particle of the consecrated Host fall from the priest’s fingers. Conversely, n the “new and improved” Mass, supposedly designed to meet the needs of modern Man who no longer needs such superstitious actions (according to the “learned”), we see the laity admitted to the sanctuary, the God of the Universe handed out like an Oreo cookie, and a profound lack of reverence for the divine.

And if one really wanted to know what was being said at Mass and did not want their attention divided in the moment, they could simply read the propers ahead of time. Most had already internalized the meaning of the Ordinary anyway. But your argument led to the “happy-go-lucky” ICEL 1.0 translation, which I would argue did more harm to the Faith than anything that came from the liturgical reforms by dumbing down profound theological concepts into insipid banalities.

The translation of the text over the last 45 years was atrocious, and the imitating the Lutheran communion service, but it is also the secular kind of music, the elimination of almost all the ceremonial, communion in the hand, women in the sanctuary and extraordinary lay ministers of communion that did this,

Wait a minute. Your whole case is that putting the Mass into the vernacular is absolutely necessary for the congregation to understand what’s happening. Well, we did just that. Don’t go blaming the translation; yes, it was terrible, but it was written at a level “the people” could understand, especially in comparison to the new translation.

Your basic premise seems to be that “the people” shouldn’t be challenged to move beyond their comfort zone and actually study the texts of the Mass in the vernacular beforehand, or follow along in a Missal during Mass. Well, Catholics did just that for years and years and years prior to the revisions to the Mass, and yet it seems they understood the essentials of the Faith (for the most part) just fine. And what of the illiterate peasants of the Middle Ages? I daresay they understood the basics of the Faith in spite of their illiteracy and inability to understand Latin far more profoundly than use “learned” moderns.

Again was that what happened when Rome switched from Koine Greek of the Apostles to vernacular Latin c. 300 ad? etc . You are IGNORING GLARING EVIDENCE that the Catholic Church HISTORICALLY had no problem in seeing the pastoral need for the vernacular at key points of its history,

This does not deny the preparation ahead of time of the readings. that is not in conflict with what I’m saying. Once you’ve done that, when you’re in church and the Introit is being sung what kind of attention is the person needing?

I have a good way to make my case to you: Why don’t you either attend a Byzantine Catholic Liturgy in English or find one online. You’ll quickly get the point.

We are not living in the Middle Ages, where faith abounded. We are living in a Godless age in the Western world. Africa has wonderful renditions of the Roman rite in their own languages, with a very slow form of liturgical dance accompanied by repetitive chanting not of Gregorian chant but of African tones and short phrases, very joyful.

You might also find on line the Anglican usage Catholic Mass with beautiful English which we could also have borrowed if our bishops had any common sense.

I once had the opportunity of attending a Finnish Lutheran high Lord’s Supper in Finnish chant, VERY similar to a simplified plainsong Gregorian. It went on for over an hour.

You seem to think that the only vernacular is the example of the NO the last 50 years.

I’m saying that you can have the EF, more power to you, but most Americans can’t endure a rite completely in Latin and it is for THEM that a traditional rendition in the vernacular with much but not all of the ceremonial of EF would be MORE EVIDENTLY DIVINE ( with the restorations that dropped out since Trent would really be what the texts of Vat II on Liturgy wanted.

Americans can’t endure a rite in Latin, huh? What weak sots we’ve all become then. A pathetic commentary on Catholics in the USA — that the Mass cannot be endured if it is not in English. Christ once said, “Can you not watch with me one hour?” According to you, no. I choose to believe otherwise.

So where does that leave deaf people, eh? Only illiterate, non-deaf, people are saved?

C’mon, get serious! “Faith comes from hearing” is not meant to be taken bald-faced literally.

You don’t seem to know what RECEPTIVE hearing of the HEART is.

That would only make sense if Mass is classroom course or an apologetics session or a catechetical class.

It isn’t.

It is worship.

Once you have attended this often you enough, if you are reading the translation, you will LEARN Latin. You will pick up this ancient and beautiful language.

I do not attend a Latin Mass. Masses around my area are Novus Ordo. But I do get the why of the Latin Mass.

For one thing, it is not just the language, the Latin Mass is quite different – in reverence and in rubrics. We have lost much in the change to the Novus Ordo.

Do you know what lectio divina is? It is a receptive LISTENING IN THE HEART to the Word proclaimed, sung, preached, so it is absolutely NOT A CLASSROOM HEARING OF THE INTELLECT ALONE. It is not a matter of intellect alone, It is what the Blessed Mother did “pondering in her heart” of the whole person as a unity. This does not contradict the rest of what you said

Yes. And Mass IS NOT the time for Lectio Divina. You do that in your own prayer time. Or you can gather with some friends to do it in common.

You are confusing Liturgy and private prayer.

So, what kind of attitude should a Catholic have attending Mass? What is the attitude when the Introit is going on? What sort of attention is profitable for listening to the readings? Lectio divina is private because of what is being read, NOT BECAUSE OF THE ATTITUDE of receptive listening of the Heart. Just as adoration of the Sacrament is private devotion outside of Mass, but it obviously occurs ALSO at Mass. It is by way of the RECEPTIVITY of the worshiper that the very Gregorian Chants developed in the monasteries of Europe that Rome came to accept.

God speaks through the liturgy and one hears that personally through the liturgy which AROUSES A PERSONAL RESPONSE. One must quiet oneself for that listening Opposite is the forceful assertion of the “O mighty Fortress is our God”

You are assuming that the personal response can come only from hearing in the vernacular.

Do you really think that those who go to Mass even pay attention to what the priest is saying? People go on auto pilot at Mass during the Novus Ordo.

And you are assuming that desire for the vernacular is self indulgent emotionalism that does not realize that Our Great High Priest offers the Mass.

My argument started with HISTORICAL FACTS about the Roman Popes switching to popular Latin in c. 300 ad. from the Koine Greek the Liturgy usded since SS Peter & Paul founded the Church there. Why did they do THAT?! Was it because they were emotionally self indulgent and weren’t aware that Christ was offering the Mass as you judge anyone wanting the change to vernacular today has that motivation? Why also did St Pope Nicholas I the Great APPROVE SS. Cyril & Methodius creating first the Glagolithic alphabet and TRANSLATE THE ROMAN MASS INTO OLD SLAVONIC (called the Liturgy of St. Peter , which was used in Croatia from the 9th cent until the Franciscans went there and replaced it with the Latin Mass in the 13th cent.? (used 300yrs; yes, the Roman Liturgy not in Latin but in Slavonic that long a period). Why were there discussions before the Prot. Revolt in the Catholic universities about translating the Liturgy in the vernaculars after the invention of the printing press?

And why did the Armenians switch from koine Greek and Syriac to their own , and the Coptic, and the Melkite Byzantine from Greek to Arabic TODAY, the Ethiopians, WHAT IS THE PRINCIPLE BEHIND ALL OF THESE switches? Are they emotionally self centered and unaware of the Heavenly Liturgy’s High Priest?

The proper distinction is between the intuitive mind and the rational mind.The latter is LESS personal.

Language is essentially intuitive, as is the language of love and poetry, the language of the HEART, like Sacred Heart, Immaculate Heart. (Right now there is a series on the meaning of Heart by Tim O’Donnell, president of Christendom College on EWTN; he started out on what the Heart means in SScripture)

What I have been saying is that FAITH comes through HEARING and for CENTURIES MOST HAVE NOT BEEN IN A POSITION TO READ AT ALL. BUT THEY WERE PREACHED TO AND READ TO AND HEARD MOST OF THE MASS IN A LANGUAGE THEY COULD UNDERSTAND. because THAT WAY God can touch them personally without their having to actively work at figuring what they were hearing by READING from a book while the liturgy goes on in another language they don’t understand. thus being more rational than intuitively receptive.(that may be necessary in some circumstances). AND the High Priest WANTS HIS PRIESTLY PEOPLE TO CO-OPERATE IN HIS SACRIFICE.

Knowing the American people as a large generality MOST will want it in their own language. I remember when the Interim Missal was used (St Joseph Missal translation from 1965 to Advent of 1969) most REALLY APPRECIATED THAT It was a good rendition. But at the same time the CEREMONIAL was drastically reduced, and the priest faced the people, etc. The NO imposed by Paul VI was an inferior rendition to the Interim,

What I’m proposing is a rendition that keeps much of the traditional ceremonial, a restoration of some things to the Calendar. Vernacular chants based on Gregorian (now starting to happen) and a better way of restored traditional additions (concelebration, the petitions, both species (by the priest intincting the host and placing it on the tongue) etc.

But I’ve said that the Tridentine Mass should be able to expand as much as people want it. In America, Most will won’t go for that.

If you are well versed in Lectio, surely you would know that one can be in a receptive attitude and actively participate in the liturgy without necessarily twirling over the words in your mind at that exact moment.

It’s good that you gave the Gregorian Chant as example. I love listening to the Gregorian Chant even when I don’t know exactly what the words mean. It conveys by it’s very nature worship of God. There is a something that transcends the calculations of our minds.

I am of course not advocating that we not understand what goes on at the Mass. You can still know what is going on even when it is in Latin if you apply yourself to it.

God can speak to you and you will be able to hear Him even if the words are in Latin.

Oh yes.

I once spoke to a priest monk who was educated pre Vat II and endured philosophy and theology instruction in Latin. He couldn’t understand a thing for 2 years and then suddenly did. He was arguing with me that Latin was a living language and I was arguing that if it was taken in through the eye, it was not very living, but if it came through HEARING it was for that person, so when he volunteered this info…Bingo. made my point.

But in the same monastery, which did all the Liturgy in the traditional way a much younger priest monk said that he just realized that week that psalm 22(23) which opens in Latin as ” The Lord rules me..” was the psalm “The Lord is my shepherd”! He had learned Latin through the eye and had been in the monaster 7 years.!!

I forget when it began to happen, but just about when Latin dropped out of Church use, linguists in secular education began teaching Latin to high schoolers AS A LIVING LANGUAGE, through the ear. Fr Pacwa said that’s how he was instructed in it, and when years later on EWTN he said that he had just heard some students talking Latin conversationally, he understood everything.

Pete, again you are confusing issues.

Like I said before, we are not talking about the classroom here.

There is no point in responding if you will not learn to make THAT distinction.

The H&PR argument is entirely phoney. It is clearly written by someone who experiences the power of the traditional Latin liturgy but who needs to concoct an excuse to run back to his post Vatican II ‘papa’.

About 5 months ago. I had a strange thought just pop into my head regarding the recitation of the rosary and the Mass. I thought “If the faithful would begin reciting the rosary in latin, God would restore the latin Mass unto us”. I know it might not really be that simple, but I have since learned most of the rosary prayers in latin and I have become quite “comfortable” with them. Just so you know, it isn’t too difficult because if I (someone touched by autism) can learn it, anyone can.

Learning the words is not a challenge. Actually internalizing what the words mean when reciting them, however, is where I struggle. Our priests quite often will say the Agnus Dei and always the Tantum Ergo, Sanctus and a few of the other prayers/responses in Latin during the Masses. I’ve learned these, but while trying to actually say them, they have no meaning for me, as I just can’t seem to even pay attention to what I’m actually saying when I do. I have no problem with using the Latin. In fact I kind like it, but it sure doesn’t seem prayerful for me to participate in that way since it becomes such a distraction for me.

When I first converted I was also distracted during Mass (Novus Ordo) by a good many things. It took a good long time to get to the point where I had internalised everything enough just to be ‘prayerful’ instead of just ‘working it all out’.

I have gone to the Latin Mass now for 12 years. It was the same in the beginning as with the Novus Ordo but after a time, the same again, I became familiar with the Mass, Latin and all.

If it’s a distraction you probably just need a little more familiarity with it yet. Perhaps try to learn the meaning of the Latin? As with learning any new language you won’t feel comfortable with it overnight. It takes repeating it over and over again. As it does with learning anything.

There is a REAL DIFFERENCE between the two usages. N.O. IS NOT MANIFESTING THE DIVINE ENOUGH. The old usage you can’t ignore the Divine, even if you don’t understand a word. I don’t think it’s JUST the languages. Facing EAST immediately changes the atmosphere, inspires silence.

I note how the people often do not look at Christ on the Altar during Mass BUT AT THE PRIEST LOOKING AT THE SACRAMENT. All that changes when as of old the priest faces East leading the people.

You and millions of Catholics. Just what I wrote above. I guess by your testimony the LONGER LATIN TEXTS of the Creed on Sundays and Solemnities or even the Gloria looses you half way through. This is a common American experience. For the great MAJORITY of Americans. Thus the need for good English texts and Chants for the changeable parts of the Mass for sure. But there are others who follow the Traditional Rite with edification. All power to them,; as many congregations that want that, should be able to get that. But MOST American congregations can only endure a few short touches of it.

Because we have become soft as Catholics, however, any Catholic can do it with fortitude, and all things are possible with God. Also, just as fathers of families have to make hard decisions for the benefit of the family, the spiritual fathers in the Church have to make hard decisions as well. And being soft with Catholics with things such as abstinence and fasting over the years, definitely makes it harder for Catholics to make sacrifices for Jesus Christ and his Church. But again, it can be done, and we mere humans are good at finding reasons(excuses) why it supposedly cannot be accomplished.

Lastly, here is a quote from Bishop Fulton Sheen back in 1956, 60 years ago. He was talking about our nation, but you could apply to the Church as well today.

“Love without sacrifice is sentimentalism, or romanticism. It is softness! It is the rottening of our nation”.

Excuse me,what about the HISTORY of ROME switching from NT Greek from the Apostles back to VERNACULAR LATIN in 300 ad, and what about SS Cyril and Methodius creating the glagolithic alphabet FOR THE ROMAN RITE in Old Slavonic in Croatia used exclusively from the late 9th cent. into the 13th cent.; what about Pope Nicholas the Great and successors APPROVING THE SLAVONIC VERNACULAR AWAY FROM NT GREEK FOR THE BYZANTINE AGAINST GREEK OPPOSITION!

These MAJOR CHANGES IN THE LANGUAGE ARE NOT “Love without sacrifice, or romanticism nor did these changes rot those nations, BUT ACTUALLY FOUNDED those nations! (and what about the Syriac liturgy dropping Apostolic Greek and choosing the vernacular Aramaic and Syriac Aramaic,VERY EARLY, And the early creation of Coptic and Armenian away from Apostolic Greek (and Syriac for the latter)?

The Roman Church HAD TO KEEP LATIN before the printing press. If you could read, the only language to do that was Latin FOR CENTURIES.

I propose you read Christine Mohrmann’s treatment of liturgical language — she demonstrates quite compellingly that the Latin which was developed for liturgical use was certainly not the vernacular (indeed, in many places and specifically among certain classes, Greek was far closer to a lingua franca).

Using capitals does not enforce your point of view. You point to exceptions from the Latin, although, this was not the norm. Also, why didn’t the Church start using the vernacular after the printing press in the Mass? Latin in the Mass kept the Church universal and not national.

Also, when Church leaders knew Latin in the past, there was more precision and clarity with official Church documents. Now there has to be translation for any gathering of Bishops from around the world. We see from the last Synod how one word not translated correctly can lead to confusion and even error. And this comes back to my point of softness, as we have stopped teaching Latin in Catholic schools, and more importantly in the seminaries at a detriment to the faith.

The only One who knows no mystery is God. For everyone else, mystery is a component of ourselves and of everyone we know; it’s a component of how we know. No personal encounter stripped of mystery can be called authentic.Rationalist reductions are a poor basis for human relationships, and a fortiori (that’s Latin) in our relationship with God. The liturgy is an encounter with the Holy, whose otherness is signified at multiple points by veiling: veiling with cloth, with silence, with posture, and with a language reserved for sacred business.

Do you read your bible in Latin or English?

A liturgical spirituality is about the ACTUAL TEXTS OF THE LITURGY and only rarely other texts that complement those actual texts.

Both, since you ask. But I am not sure what your point is.

Quoting from the article reviewed: “Is it possible that the Traditional Latin Mass, though beautiful sounding Latin, merely makes one feel good (?)” Maybe, for some. But it’s a short trip from “feeling good” to being prayerful. And in almost fifty years of (scattered) attendance at the New English Mass, I have never felt good. I’ve never been to one where I didn’t sense that something was missing.

“Ah-men.”

I spent six months in Spain on deployment. I frequently attended Mass at local parishes even served at the altar without a functional understanding of the Spanish language. The fact is that the Mass is the Mass and my ability to pronounce the responses is unnecessary for the Holy Sacrifice to be realized. It is our own arrogance that forces us to feel so important.

Of course, that is how all the centuries of non-educated faithful WHO WERE CATECHISED TO KNOW THAT WAS WHAT WAS GOING ON BENEFITTED, but soon the beginnings of the Rosary began and took centuries to develop because the ordinary people needed somehow to no just watch but be engaged in the Mass. It is not arrogance but just normal human nature.

Are you suggesting that my participation in the Mass is necessary the validity of the Eucharist?

#1 No, where did you get that idea from from what I wrote. By the way are you disputing the history I presented? or ignored that because it was inconvenient? Where and how did the Rosary develop over the centuries and why was being said during Mass by those who couldn’t read (the overwhelming majority in the early Middle Ages and beyond? were they not also looking at the painted imagery, statues later stained glass windows for SUSTAINING THEMSELVES DURING THE LITURGIES. And they picked up by hearing the ordinary parts of the chant with no choir practices. That is by HEARING.

#2 YES

I’m neither rejecting nor ignoring your history. My point is that our participation in the Mass or ability to understand it have no effect on the Grace we receive from it. The sacrament has the same effect whether it’s in Swahili or Klingon. The “feel good” desire is solely our human nature. Once we divorce ourselves from our human longings and allow the Mass to be purely about glorifying God, we can see what the Mass truly is.

Brian Williams clearly articulated the crux of the crisis in the Church when he explained the truth that: “The Mass is preeminently the prayer of Christ, the offering of the Son to the Father, in which we worship and adore the Son, and join in his offering to the Father. It is not, first and foremost, our prayer. It is Christ’s prayer. It is the heavenly liturgy, into which we are privileged to take part.”

The reality and understanding of the Mass as preeminently the prayer of Christ is completely absent in the Novus Ordo. It is, in fact, preeminently a purely individual, subjective, devotional experience, designed to please man rather than God. That is why I must object to Bishop Schneider’s assessment that “the Novus Ordo did not contribute to the crisis in the Church.” It was the central factor in contributing to the crisis in the Church because it clearly rejected the Mass as “preeminently the prayer of Christ” and by doing so, forced its participants to focus on themselves rather than on Christ. The entire liturgy of the Novus Ordo is a diminishing of the Sacrifice, making it secondary to, and almost invisible, the gathering of “the People of God” as a mere devotional experience.

I agree, BUT what we have for the last 50yrs is NOT what the Vat II says; it is what unsure Paul VI gullably sign off on that we got. And he was warned by Patriarch Athenagoras of the Orthodox, when he met the Pope in Israel in 1969 before the changes took place that Advent NOT TO CHANGE THE LITURGY, JUST TRANSLATE IT. The Pope ignored this Successor of the Apostles and gave in o sons of the Prot, Revolt and rationalists of the 17th century instead. Story is told that when Paul VI went to his Mass on Pentecost Monday and the vestment was green, instead of red for the Octave. HE asked it to be changed and the priest responded with but there is no longer an Octave of Pentecost. The Pope burst out crying! Unbelievable, he cried, but did not CORRECT THAT IMMEDIATELY, by telling the priest to put out the red and inform the Church the the Pentecost Octave would continue. Do you really think that the majority of the Fathers at Vat II had any idea that the entire Octave of the Holy Spirit for Pentecost WOULD BE ELIMINATED?!

“Do you really think that the majority of the Fathers at Vat II had any idea that the entire Octave of the Holy Spirit for Pentecost WOULD BE ELIMINATED?”

By studying the history and goings on in both the Church and world since the French Revolution, Protestant revolt, WWI, WWII, and the rise of Communism, Socialism, Liberalism, the sexual revolution, the Masonic infiltration of the Church, the spread of heretical works condemned by various popes throughout the Catholic clergy, universities, and seminaries, the acceptance of Darwinian evolution, and the general trend of the people of the world away from believing what is true, I do think that the majority of the Fathers at Vat II were dissenters against the faith, were imbued with Modernism and knowing the tendencies of John XXIII to be liberal (or worse, a defender of Communism and more), and their election of one of the most confused men in Church history, Paul VI to the papacy, they jumped on an opportunity they never had before and knew their time was limited to, not reform, but transform the Catholic religion into their Modernist/Pantheistic/Masonic religion.

That is exactly what they accomplished. And they did so by creating the documents within the Council with purposeful ambiguity so they could be interpreted as both orthodox and unorthodox while knowing as well that in practice, their unorthodox, anti-Catholic Modernist heresies would be taught and eventually, the Catholic faith destroyed.

If Patriarch Athenagoras had warned Paul VI, he was not the only one. Cardinals Ottavani and Baca and a group of theologians presented Paul VI with a critical study of the serious problems they found with the Novus Ordo. Of course, Paul VI ignored them.

Paul VI may have cried but he signed off on every Vat II document and in every address he made before, during and after the Council, misled Catholics through his own ambiguity and cowardice and he could have stopped the whole catastrophe at any time if he wanted to.

I agree overall, but I distinguish Between John XXIII and Paul VI the former was actually quite conservative His first decision was to proclaim that Latin was to be maintained at the Roman schools of theology in the Roman Synod he held before the Council got started, which by then had Italian as the language: but times had already changed: most profs could not teach in Latin; neither could the students understand it; Paul Vi was the progressive and quite at home with a secular tendency. He was also uncertain in how to deal both with the pill and the Liturgy, the former he waited too long and his problem was not that he could change the teaching, but how to explain it aright. Bishop Wojtyl/a volunteered his writings, which ended up being used extensively in the ensuing Humanae vitae For the Liturgy he also waited and was genuinely confused. Then he was presented with a Protestant style NO, which he took with only slight changes. It was NOT what Vat II said to do.

Have you read the Ottavianti/Baca Intervention? Pope Paul VI did absolutely nothing to address their serious concerns about the “reforms” of the Mass.

http://www.catholictradition.org/Eucharist/ottaviani.htm

Yes. What should have happened is to continue the slow well thought out restorations and adjustments of Pius XII. If the Pope had followed Patriarch Athenegoras’ wise counsel, there could have been GREAT continuity in the Liturgy.

The millennial long persistence of Latin in the Liturgy of the Roman Church is a fluke of history, and it was NOT absolute in at least one place (e.g. Croatia, where the Roman Mass was in Glagolthic from the ninth century on until the Franciscans came in the 13th! replacing it with Latin).. It was due simply because of the Germanic peoples invaded the Western part of Europe trying to get along in Latin and quickly started developing the Romance languages WHICH WERE UNWRITTEN AND EXTREMELY VARIOUS WITHIN SHORT DISTANCES, thus needing to keep the Latin for Liturgy. (For the same reason, the papacy had political control of central Italy for 1200yrs and this was absolutely an accident of history non essential in itself).

They were also developing the Teutonic languages.

Contrast the Byzantine conversion of the Slavs who all spoke the same Old Slavonic for centuries, which could be understood, and was written down for the Liturgy, one language from Russia to northern Greece

And don’t forget that the Church in Rome was one of the first to switch to the return of Latin itself as the popular language replacing koine Greek c. 300 ad and in N. Africa slightly earlier, as bilingual Tertullian, who gave the Latin Church its theological terminology shows.

And don’t forget that Pope St Nicholas I the Great and his immediate successors APPROVED the Slavonic vernacular for Divine Liturgy to replace the Greek.

With the creation of the printing press, the western vernaculars had developed so much and could now be printed that the idea of switching the language of the Liturgy to the vernaculars.began to develope. Calls for this occurred BEFORE the Protestant Revolt, but ever slow Rome hesitated, and the Prots, seized the opportunity making the spread of heresy far more likely with the vernacular. Hence Rome froze the Latin Liiturgy and just universalized one variation for the whole Church. EXCEPT FOR THE BIBLE, which actually came out before the Prots could do it for the English to be for sure.

Now as for America. We are historically impatient in learning new languages as a whole (and MOST of. first generation born here of immigrants loose their parents tongue) The ORIGINAL languages of the Liturgy were ALL IN THE POPULAR VERNACULARS and changed to the vernaculars when needed).

As PRACTICAL matter all PROPER texts need to be in the vernacular.like the present Eastern Churches, with some NON CHANGING, relatively short and important prayers left alone.

For most Americans that would mean keeping the SHORT ordinary parts (Kyrie, Sanctus, Agnus Dei in mixed congregations the Pater Noster too) in the Latin, But the Gloria, Creed are too long for Americans to ingest meaningfully.

One should have the same RECEPTIVE , LISTENING ATTITUDE in the Liturgy (as in lectio divina) that allows one to be touched by the Holy Spirit during the Liturgy, and for THAT reason the vernacular is practically necessary for most Americans (not all, however, so that the TLMass should be available for any community that really wants it.

Mystery can be attained in the Rites by other means (facing East from the Offertory one, and when directly talking to God, like the Petitions), no Communion in the hand, or women as servers of any sort in the Sanctuary perods of silence, and ABOVE ALL THE MUSIC that actually lifts us to God.

http://www.papalencyclicals.net/John23/j23veterum.htm

‘But the Gloria, Creed are too long for Americans to ingest meaningfully.’

So Americans are a little bit…dull. Surely not! Guess us Aussies are better after all 😉

It would have made more sense if you said the gospel, but even this is read out after in English (in my parish anyway).

I would guess so. Don’t your youth learn more in high school like Europe; We get serious about education much later, by which time they loose their faith and morals.

The Latin Mass has never been ‘just for the educated’, it is the treasure of all, able to be understood by all. It could be argued that many times the poorest and least educated have ‘understood’ it best. And it is in part, for the reason you have given below, ‘The old usage you can’t ignore the Divine, even if you don’t understand a word. I don’t think it’s JUST the languages.’

As to education in Australia, sadly I fear it is no better than anywhere else at this current time which is why I home-school.

God bless you Mr. Salveinini!

Well, you’ve obviously made the right decision for your children, which is growing more and more here, which I applaud you for.

But I know Americans are overall not happy with languages they can’t understand. They expect others to have some English and get impatient with attending Spanish or Vietnamese liturgies.regularly and really get peeved if their new priest in their parish has a strong African or Indian accents

I’m saying there IS A WAY to render the Roman Rite with the same Divine emphasis as the EF predominantly in the vernacular for what MOST Americans would SEE is a continuity with the past. That is what Benedict meant when he said the EF must be the standard for the application of what Vat II wrote. So I’m all for any congregation that wants the EF. By the way, this is just what the Ruthenian Byzantine Catholics do in most of their parishes: English with the traditional ceremonial and music.

Thanks for your input,

Well, that’s a rather condescending view of Americans you have there. If we’re so incapable of comprehending the meaning of the Gloria and the Credo in Latin, then I guess all the pre-Conciliar American Catholics who suffered through them for generations were simply wasting their time.

non-sequitur. Attention span for most Americans is only 7 minutes. Remember our forbears here DID prepare themselves several ways. Today’s people gereally do not, although that is changing for the better now than from 1965-’85

Well, golly gee wilickers. If Americans are so incapable of focusing for any length of time, then why not just cut the entire Mass down into something like this:

Priest: The Lord be with you.

People: And with your spirit.

Priest: Come forward and receive the Lamb of God, Who I have consecrated before Mass to save you time.

(Communion reception)

Priest: The Mass is ended.

People: Thanks be to God.

I mean, really. Shouldn’t we at least try to do better than our statistical average at the most important thing we do each week? And besides, it really doesn’t matter if “the people” understand and appreciate everything at Mass, anyway. The prayers are directed toward God, not toward the congregation.

NO not all the texts are directed to God The readings are directed to the congregation, and they are proper texts (changeable) at each Mass They NEED TO BE VERNACULAR ALMOST ALWAYS. As are the responsorial psalms alternating with a schola and congregation

AND some of the prayers addressed to God are FROM THE WHOLE CONGREGATION,The entrance antiphon and verses alternate between schola and congregation; the Kyrie, Gloria, as also the Creed, The petitions are shared with the congregation, offertory hymns also; Sanctus, acclamation after the Consecration, Great Amen, Our Father, Agnus Dei. Communion antiphons and hymns can be also.

I don’t think you are really listening to my argument. I am NOT DEFENDING THE PRESENT RENDITION OF THE NO, as it is NOT A GOOD APPLICATION OF VAT II TEXTS ON LITURGY. which I have explicitly stated. I am saying a FAR MORE TRADITIONAL RENDITION OF THE EF, WITH SUITABLE RESTORATIONS FROM THE HISTORY OF THE ROMAN RITE, (GLARINGLY restoration of the permanent diaconate! established by Apostolic Authority from the beginning, as well as concelebration from the Apostolic beginning which had all but disappeared for centulries. Something very important went out of use. Restoration most needed..

AND I said any local community that wants to celebrate EF

ought to. MOST Americans would BE ABLE to see the value of a MUCH BETTER RENDITION THAN WHAT PAUL VI IMPOSED ON US.

Understand?

David Menconi writes some good stuff, but HPR is hopelessly trying to be all things to all people. The review it ran of Alice von H’s books was cringe-inducing, as was its gushing one of Ratinzinger’s “In The Beginning.” It’s hard to maintain credibility when you are plugging for Vatican II, the council that becomes more and more obviously jack-assanine the more distance we get. Even it it is technically governed by the H.S.

Yes, it is difficult to pray at a TLM…. for certain values of “pray,” i.e., the kind of prayer expected of you at a novus ordo (i.e., attentive listening to and real-time comprehension of audibly-spoken words as they’re being spoken). Since that’s not the only kind of prayer that can possibly exist, it’s not a very interesting objection, just a demonstration of the complainer’s benighted insularity.

AGAIN, please explain the actual History of the Catholic Church through the popes positively ENCOURAGED THE VERNACULAR FROM THE VERY EARLY CHURCH. ?

If you are talking about the 3rd century transition from liturgical Greek to liturgical Latin, you are sorely mistaken. Liturgical Latin was certainly not the vernacular form spoken either by the high or low classes, but a stylized, archaic, hieratic version of Latin, consciously patterned on the liturgical Latin of pagan Rome. The movement from Greek (which in many areas and for some classes was far more commonly-spoken than Latin) to Latin was a deliberately movement INTO dignified obscurity, not away from it.

A common sense approach:

*

Why Latin? Why a sacred language?

*

Were there a people that remained a people without a common language?

*

If the Church is the People of God [cf. Pope Paul VI], members of the household of God [cf. Eph 2:19], a chosen race, a holy nation, God’s own people [cf, 1 Pt 2:9-10], how is it the Latin/Wesern Church abandoned its sacred [holy] language of Latin, of a holy [set apart for God] nation, members of the household of God? [cf. http://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/details/ns_lit_doc_20110209_lingua_en.html%5D

*

That ‘I would want to know/understand what it is i am praying’ is the dumbest reason ever given for the use of “ordinary” or popular language in liturgical celebration, when those [include Pope Paul VI here] giving such a reason know that they were not born in a family speaking, knowing, and understanding their mother tongue, but gradually came to speak, know and understand it by first speaking it!

*

Will this cacophony reach Our Father and Our Mother?:

*

The iinovators knew very well what they were doing [they always know, they are the ‘new lights’ and they call the masses sheeple, who do not know what is good for them unless they tell us what it is].

*

Cf. A Pope of Contradictions [http://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2013/12/paul-vi-pope-of-contradictions.html#.VrlwpVgrKUk]: Pope Paul VI speaking out of both sides of mouth.

Of Mass in the vernacular one can justifiably say: This is not the source. This is not the summit.