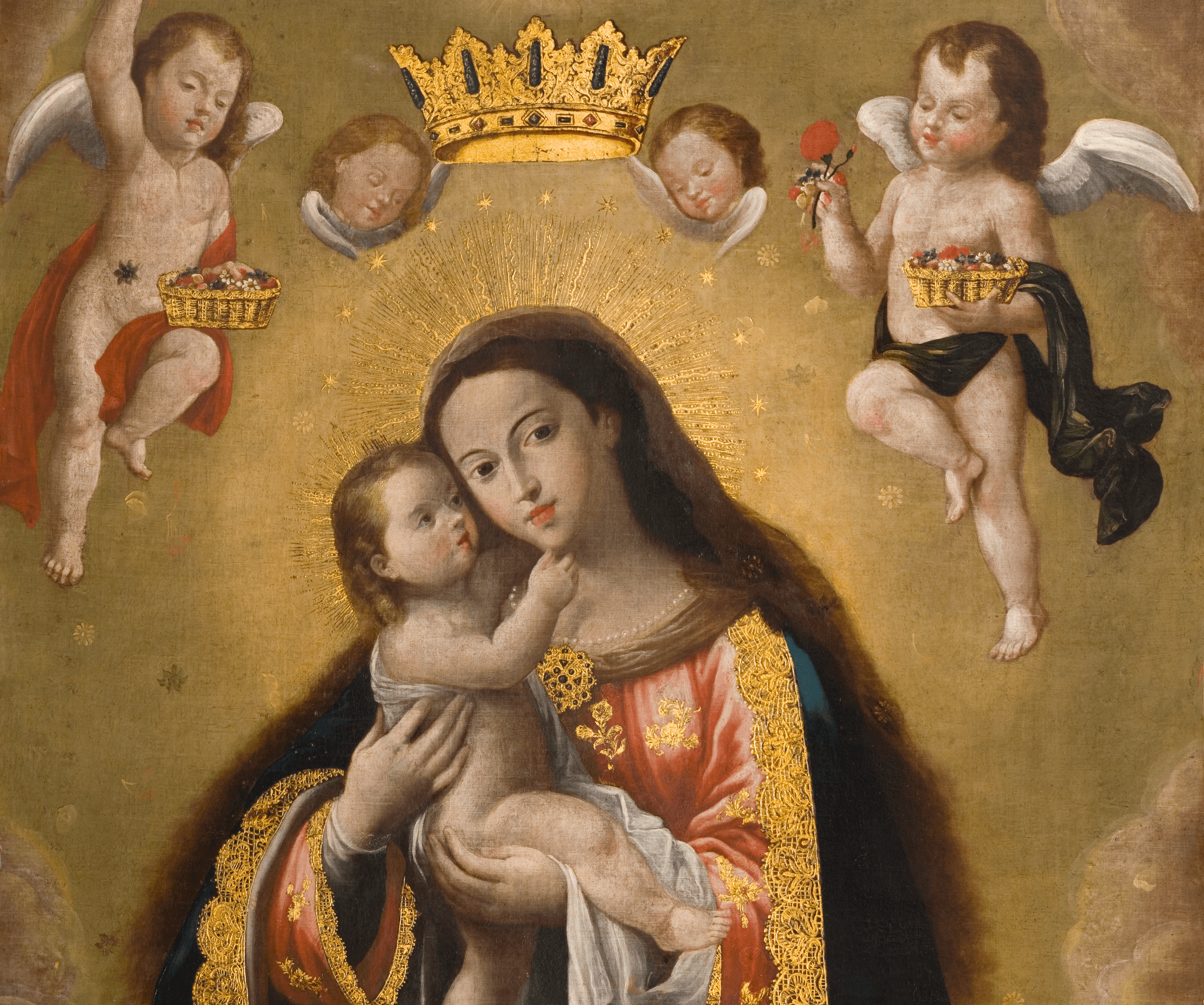

Art and the Female Principle

Other than Our Lord Jesus Christ there has been no more frequent subject in Western figurative art than the Blessed Virgin Mary. If the object of the arts, when rightly ordered, is beauty, then it is fitting that the inspiration of so much Western material and musical culture be the Lily among thorns, the House of Gold, the Mother of Fair Love; She who is the most beautiful creature. Our Lady is God’s supremely perfect ‘work of art.’ What the artist does to matter is remarkably similar to what grace does to persons; namely infuse and transform nature. Through art, matter partakes of the rationality of the artist and is suffused with it. It can be said that there is therefore something analogous between the artist and the saint.[1] Throughout Christian history there has been a mysterious and abiding relationship between the Queen of the Saints and those diverse crafts, practices and artefacts that constitute ‘the arts’ and give voice to man’s soul. In his landmark Civilisation television series, the art historian Kenneth Clark famously commented on this relationship:

“In the early twelfth century the Virgin had been the supreme protectress of civilisation. She had taught a race of tough and ruthless barbarians the virtues of tenderness and compassion. The great cathedrals of the Middle Ages were her dwelling places upon earth. In the Renaissance, while remaining the Queen of Heaven, she became also the human mother in whom everyone could recognise qualities of warmth and love and approachability…

The stabilising, comprehensive religions of the world, the religions which penetrate to every part of a man’s being – in Egypt, India or China – gave the female principle of creation at least as much importance as the male, and wouldn’t have taken seriously a philosophy that failed to include them both… It’s a curious fact that the all-male religions have produced no religious imagery – in most cases have positively forbidden it. The great religious art of the world is deeply involved with the female principle.[2]”

In the creative process the artist incarnates, in new forms, that which can be grasped only by a rational nature.[3] We might say that the reason that religious art is so involved with the ‘female principle’ is that the artistic initiative corresponds to the initiative of the masculine, having been inspired by the feminine (for example, ‘mother earth’), which then fructifies the feminine and produces beauty. Given that God has given us the Image of Himself in His Only-Begotten Son, through the Blessed Virgin Mary, art – our creation of images – has totally changed as a result of the Incarnation. Here we may begin to understand why the cult of the Virgin had been so central to the great artistic flowerings of the High Middle Ages and Baroque periods among others.

The Beauty of Our Lady

In 1665 the masterful Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini addressed the Royal Academy in France and stated that because of Original Sin and the Fall “nature is always feeble and petty” and that “nature itself is devoid of both strength and beauty; artists who study it should be skilled in recognising its faults and correcting them.”[4] Bernini was most emphatic in his address that artists should strive for material perfection in regard to any depiction of Our Lady. Our Lady is the second Eve, preserved from Original Sin to bear Our Saviour, and while sin and death entered the world because of the disobedience of Adam and Eve, Mary was full of grace because of her obedience, and did not experience aging and death. She should therefore be depicted idealised and perfect, without proportional or compositional blemish.

If in modernity man has largely lost sight of Beauty it is because he has lost sight of the other transcendentals of being: Goodness and Truth. The three transcendentals are convertible and thus must be apprehended and received together. The contemporary religious sculptor Cody Swanson has commented that the steep decline in contemporary beauty in art also comes from a lack of belief in our descendance from Adam and Eve. Rousseauian anthropological optimism – the denial of Original Sin and the “belief that we were all immaculately conceived” as Archbishop Fulton Sheen remarked – has taken deep root in the modern mind and imagination, preventing us from comprehending the penumbra of our own fallen state and by total contrast the beauty of the second creation of grace, begun with Our Lady. (This denial of the ancestry of our first parents was of course repudiated even quite recently by Pope Pius XII in Humani Generis where he outright refuted polygenism.)

The Mariology of Modernity

Within the Theology of history, it is also possible to study the Mariology of history. In great apparitions like those of Our Lady of Guadalupe or Our Lady of the Pillar the Virgin Mary has dramatically changed the course of history to further the mission of Her Son’s Gospel. In more recent centuries she has also played a central role in heaven’s response to modernity with apparitions such as those at Rue de Bac, La Salette, Lourdes and Fatima, repeatedly calling modern man to prayer, penance and reparation; the pleas of a merciful Mother as man continues his catastrophic retreat from grace.

By correlation, the heavenly patronage that Our Lady once held over the arts has thus also become diminished, yet her motherly concern for them still seems to manifest even in the most unlikely of circumstances. To illustrate the extent to which the Virgin of Mercy seeks to extend her pallium even to the most recalcitrant of artist-sinners here are two surprising examples of her perhaps seeking to do just that.

One of the most famous apparitions in English literature is in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol when Ebenezer Scrooge is visited by three spirits who effect an interior transformation in the once cold and miserly man. A year after Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol the author was also visited by an other-worldly spirit while travelling in Italy. Raised as an Anglican, and later drifting towards Unitarianism, Dickens once told his friend and future biographer John Forster that Catholicism was a “curse upon the world.” For Dickens, religion was something genuinely ‘felt,’ but essentially private, rational and emotionally restrained. In GK Chesterton’s words he regarded the Catholic Faith as “an old-world superstition… like a moonlit ruin.”

After his trip to Italy in 1844-5 Dickens described the country as “priest-ridden”, somewhere the Jesuits “go slinking about… like black cats” and the Holy Week celebrations he witnessed as “unmitigated humbug.” During his trip however, something else happened to disturb this troubled soul. Dickens had been very close to his sister-in-law Mary Hogarth and she had died in his arms aged only 17. While he was staying in Genoa Mary’s spirit seemed to appear to him in a dream: “It wore a blue drapery, as the Madonna might in a picture by Raphael” Dickens later wrote to Forster. Dickens entreated the spirit:

“What is the True Religion? You think, as I do, that the Form of religion does not so greatly matter, if we try to do good? or,” I said, observing that it still hesitated, and was moved with the greatest compassion for me, “perhaps the Roman Catholic is the best? perhaps it makes one think of God oftener, and believe in him more steadily?” “For you,” said the Spirit, full of such heavenly tenderness for me, that I felt as if my heart would break; “for you, it is the best!” Then I awoke, with the tears running down my face, and myself in exactly the condition of the dream.

If he was visited by the Madonna this would not have been the first time the Blessed Mother had visited a non-Catholic, nor has she ceased to do so.

The rapidity of the 1968 cultural and sexual revolution was encapsulated in the Beatles’ precipitous Dionysian descent from sentimentally carnal but relatively tame love songs, to producing ballads that both encouraged and mirrored the chaotic hedonism that exploded in the latter part of that decade (manifested in the grotesque album art of butchery and headless babies). In 1963 one of the Beatles’ first hits had been “I Want to Hold your Hand.” By 1968 one of the Beatles’ songs on “the White Album” was “Why Don’t We do it in the Road,” inspired by seeing two monkeys mating in the road during their ‘transcendental retreat’ in India.

During the later recording sessions for that album, and amidst a period of depression, drug-taking and acrimony, Paul McCartney had a dream. In the dream his mother, Mary, appeared to him. His Catholic mother from Liverpool had had Paul baptized as a baby, but despite his agnostic father’s initial agreement that the children would be raised Catholic he later refused to follow through on his commitment. Mary McCartney died in 1956 of breast cancer on the day she was to have surgery. Paul was 14. Her last act was to lay out her children’s clothes for the day so they would be properly dressed if she did not return.

In the dream she spoke to her son and told him, “It will be all right, just let it be.” “Let it be” became the title of the final Beatles’ single in March, 1970. Written and sung by McCartney, with an organ-accompanied melody, the song has a hymn-like aura, which provoked mockery from John Lennon during the recording session who compared the band to choir boys. The song was nevertheless popular and prompted many fans to ask McCartney if the song referred to the Virgin Mary. He replied the reference was to his mother, Mary, but that the listeners could interpret the song as they pleased. We are left to ponder the extent of a mother’s love – was it his mother Mary who had appeared to him, or was it his Mother Mary?

When I find myself in times of trouble

Mother Mary comes to me,

Speaking words of wisdom, [Do whatever he tells you]

Let it be. [Fiat mihi secundum verbum tuum]

Art via Cathopic. Photo provided by the author.

[1] Morello, S. (2018, October 31). Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder. Retrieved from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YqNdMC4BwTo

[2] Clark, (1971 transcript), 175-176. Emphasis mine.

[3] Morello, S. (2018)

[4] Paul Fréart de Chantelou, Diary of the Cavaliere Bernini’s Visit to France (Princeton University Press, 1985), 106.