|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

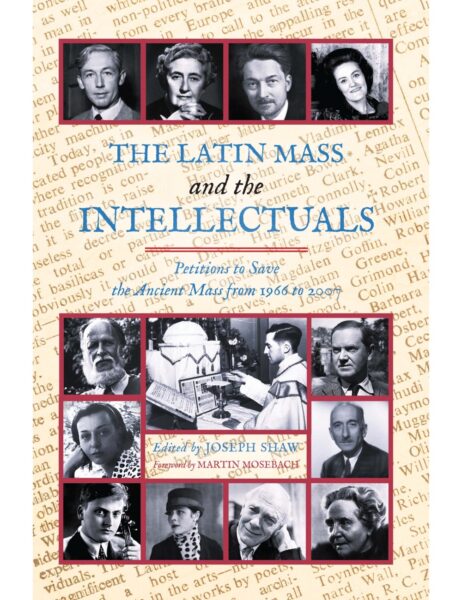

Above: Jewish pianist and conductor András Schiff, one of several significant non-Catholic signers.

All traditional Catholics know the story: that Agatha Christie and various others signed a petition to Pope Paul VI in 1971 asking him not to prohibit the celebration of the Traditional Mass, and he relented: at least, he allowed it to be celebrated publicly in England and Wales, an “Indult” (permission) that was extended to the rest of the world in 1984.

The story is told with pride, amusement, and sometimes with a little resentment. Why did Pope Paul listen to non-Catholic celebrities, having ignored Catholic voices asking for the same favour? Some take it a step further: why did the Catholic organisers of the petition seek out non-Catholic signatories? Would it not have been better to have failed to preserve the Traditional Mass, than to have preserved with the help of non-believers?

Actually, that last sentence is not usually articulated, though it seems to be implicit in the attitude of some people. I hope its absurdity is evident. Of course we should not do anything intrinsically evil for a good result, but allowing non-Catholics to express their opinion on the subject of the ancient Catholic Mass is hardly that. If these men and women were willing to sign, they must have been sincerely moved by the liturgy and sincerely grieved at the prospect of its disappearance. It was good that Pope Paul VI was made to recognise that he was in danger of bringing ignominy upon the Church by banning the TLM, and that this would be recognised even by cultured non-Catholics. It was also good that this consideration, at least, prevented him from doing something objectively bad.

The argument has arisen all over again, with a new, British-based petition organised by Sir James MacMillan, signed by 48 prominent people: musicians, artists, senior journalists, politicians from across the political spectrum, assorted cultural figures, a member of the British royal family, and a senior soldier. Like the petitioners of the Agatha Christie petition back in 1971, many are non-Catholic.

Sir James MacMillan is a composer of international reputation, a devout Catholic, and someone who has over the years engaged closely in battles over the direction of the Church. His specially-composed music for the beatification of John Henry Newman in 2010 was too traditional for some; for years he ran a humble parish choir; he has written some wonderful religious music, like his recent “Christmas Oratorio”, and he has honoured the Latin Mass Society by being one of our Patrons.

He and his collaborators made the calculation like the one sixty years earlier by the equally deeply committed organiser of the 1966 and 1971 petitions, the founder of Una Voce Italia, Christina Campo. Campo wrote to one of her assistants, only half-joking: “the fewer Catholics, the better.” But why?

The answer is very simple: those well-known for their support for a cause don’t add as much weight to a letter like this than those whose support for it comes as a surprise. A well-known supporter of a cause can make a difference by making a persuasive argument, but he’s not going to add much to a list of names under a petition. It makes sense to have some people like that among the signatories—it might seem odd if they were all missing—but the force of a petition of luminaries comes from the ones you didn’t expect.

How far do we take this? Well, Sir Benjamin Britten wasn’t a Catholic, and isn’t anyone’s idea of a Catholic role model, but he signed the 1966 petition. Philip Toynbee, who signed the 1971 petition, was a Communist; his fellow petitioner, the poet Kathleen Raine, was (according to her sympathetic obituary in the Catholic Herald) ‘repelled’ by the Catholic Church; another signatory, Djuna Barnes, was a Feminist who wrote The Book of Repulsive Women. As for the new petition, I don’t know very much about the signatory Lord Smith of Finsbury, but Wikipedia tells me that he was the first “openly gay” Member of Parliament, and also the first to acknowledge that he was HIV+. Let’s just say that his support for the Traditional Mass wasn’t on my bingo card, any more than that of George Galloway, the maverick left-winger, who told an interviewer that he thought the TLM was “poetry in motion” just a few days ago. A.N. Wilson, another signatory, has had a series of conversions and losses of faith. Many of the petitioners are paid up Agnostics, like the historian Tom Holland, or Atheists; there are also some Jews, like the musician András Schiff.

This is not to criticise these individuals: on the contrary, it is part of what makes them interesting, and makes their endorsement of the petition compelling. Cristina Campo tried to get a famous critic of the Church, Octavio Paz, to sign, joking to a collaborator “you can tell him that this letter is an attack on the ‘Church,’ which will cause more havoc than the murder of 1,000 priests.” Campo’s joke has this much truth: supporting the Traditional Mass is not something you would do if you wanted to cosy up to the Catholic establishment. This is about supporting the ordinary Catholic in the pew, against the abuse of power from above, and people outside the Church can sometimes see this more clearly than Catholics.

The support of non-Catholics is also an indication of how the spiritual significance of the Traditional Mass can be recognised beyond the boundaries of the Church, something which it does when it draws people into the Church. The somewhat tortured intellectual and emotional engagement with the Church of Kathleen Raine, Tom Holland, and A.N. Wilson, for example, are illustrations of the operation of grace, and the ancient liturgy has a role to play in that. Let us pray that Holland and Wilson accept the grace, by the end, that a 1971 petitioner, the art historian Kenneth Clark, accepted, namely, becoming a Catholic on his death-bed.

It should be said that the petitioners also include many devout Catholics who give it weight for different reasons. For example, another Patron of the Latin Mass Society, Lord Moore (Charles Moore), a former Editor of the Daily Telegraph and potentially an establishment figure, is nevertheless willing to put his head above the parapet for this cause; Sir Rocco Forte is a similar case, as is, most obviously, Princess Michael of Kent.

In a different category are those who have done important work in apparently unrelated areas of the Church’s life. It is a great honour to see here the Catholic peer Lord Alton (David Alton), who has fought the good fight for the pro-life cause and human rights since being elected to Parliament in 1979, and Baroness Monckton, a redoubtable champion for Downs Syndrome children. Again, it is well known that Fraser Nelson, the Editor of the Spectator, and Adam Zamoyski, the distinguished historian, are Catholics, but they have never been associated with the cause of the Traditional Mass before. These are intelligent, cultured, successful, and sensible people: and yet—our opponents might exclaim!—they support this eccentric and forlorn cause.

May God bless each and every petitioner, and let us all pray for their good estate.