Each year the Latin Mass Society of England and Wales organises a High Mass at England’s neo-Byzantine mother church, Westminster Cathedral, to coincide with its Annual General Meeting. This year’s High Mass on the Vigil of the Assumption was as majestic and liturgically sumptuous as ever, with a possibly record attendance of 350 – 400 people (see photo of above from the event). Among the faithful there was a quiet but perceptible air of determined resolution. Despite the promulgation of Traditionis Custodes, devotion to, and interest in, the Apostolic Roman Rite only continues to increase in England and her bishops are rather wary of how to ‘implement’ the recent motu proprio while dealing with the only part of the Church experiencing such inexorable growth. Growth, which according to their post-conciliar formation, represents retrogression against the ‘laws of history’ and thus, was never meant to occur.

History of the Latin Mass in England and Wales

The traditional community in England and Wales is of notable importance to the wider traditional movement. One of the unbroken streams by which Divine Providence saw fit to continue the flow of the Church’s Liturgical Tradition to the present, following the post-conciliar official hostility towards that Tradition from many quarters, was in England and Wales through the famous ‘Agatha Christie indult’ of 1971.

For those readers unfamiliar with this rather curious episode some exposition may be helpful: in 1965, before the Second Vatican Council’s final session had closed, the Latin Mass Society was established to promote the Traditional Mass and all its riches in England and Wales. The LMS was, and is, a lay movement that represents a rare example of successful lay activism that has had some degree of influence on episcopal policy. The LMS was also an Una Voce Federation founding member and has supplied three presidents over the decades, including the famed Traditionalist writer Michael Davies. The society continues to be the best resourced Una Voce group in the world with a small full-time staff and permanent office.

During the heady foment of high modernist enthusiasm following the closure of the Council in November 1965 the officers of The Latin Mass Society sent an appeal to Pope Paul VI that “the discontinuance of the use of the Latin tongue in parts of the Mass has proved a grave spiritual privation and a source of great anguish of soul.” Alas, despite the personal sympathy of the English primate Cardinal Archbishop John Heenan of Westminster towards the pleas of England’s laity, the Roman Curia remained unmoving. With the promulgation of the Novus Ordo Missae in 1969 and the seemingly imminent ‘obliteration’ of the Apostolic Roman Rite an alternative plan was conceived to enlist the support of various prominent non-Catholics who would join the plea of the LMS faithful to save the Old Rite not just for its spiritual nourishment but as a cultural treasure of Western Civilisation. A section of the appeal surmised:

The rite in question, in its magnificent Latin text, has also inspired a host of priceless achievements in the arts – not only mystical works, but works by poets, philosophers, musicians, architects, painters and sculptors in all countries and epochs. Thus, it belongs to universal culture as well as to churchmen and formal Christians.

In the materialistic and technocratic civilisation that is increasingly threatening the life of mind and spirit in its original creative expression – the word – it seems particularly inhuman to deprive man of word-forms in one of their most grandiose manifestations. The signatories of this appeal, which is entirely ecumenical and non-political, have been drawn from every branch of modern culture in Europe and elsewhere.

Among the signatories were cultural luminaries such as Graham Greene, Iris Murdoch, Kathleen Raine and Cecil Day Lewis. Something about the ‘ecumenical, non-political and modern’ nature of the appeal, as well as the support of Cardinal Heenan, perhaps helped it secure serious consideration. According to legend, when presented with the petition Pope Paul VI ran through the list of signatories and alighted on the name of Agatha Christie, author of the Poirot series of which the Pontiff was fond. “Ah, Agatha Christie!” he exclaimed and signed his approval. The bishops of England and Wales were thus authorised to grant permission for the ‘occasional’ celebration of the Old Rite Mass

Although, as we are all aware, the Old Rite of the Mass was never abrogated, that was not the impression created in the extreme ultramontanist mid-to-late twentieth century. In 1971 the semi-official newspaper of the English Bishops’ Conference ‘The Universe’ published a front page that proclaimed:

As from this Sunday, the first in Advent, it is forbidden to offer Mass in the Tridentine rite anywhere in the world. In very special circumstances old or retired priests may apply to their own bishop for permission to use the rite, but for private use only.

Nevertheless, providence had marked England as a place where Tradition would be preserved and, in time, slowly come to flourish. The English (“Agatha Christie”) Indult of 1971 ensured that the Apostolic Roman Rite continued to be found in tucked away corners of the English landscape – with episcopal approval – whereas in many more historically Catholic countries, outside the SSPX, the Apostolic Roman Rite was all but stamped out. The reasons for this notable difference in liturgical fortunes are difficult to fully comprehend. My own belief is that the Anglophone bishops possess a certain native ‘cultural liberalism’ where pluralism, including in liturgical matters, is not only tolerated but even celebrated. Hence, one group of Catholics can have their charismatic Mass, another their Neocatechumenal celebration, another can have their Old Rite Mass, perhaps another can even have their ‘LGBT Mass.’ Just so long as they all rub along and don’t become too assertive in the superiority of their liturgy.

Bishops from more Catholic countries on the other hand have imbibed a theological absolutism that is the legacy of a once truly Catholic objectivity. Therefore, when the ‘objective standard’ of the liturgy changed in 1969, or was perceived to have changed, they adhered to that new single liturgical expression with all the zeal once given to the unchanging truths and expressions of the Faith. The hostility of bodies such as the Italian Bishops Conference to the Old Rite Mass can be understood in this way. The Old Rite is viewed with consternation as the liturgical expression of ‘the old Religion’ which has since ‘evolved’, and, even been replaced.

Summorum Pontificum

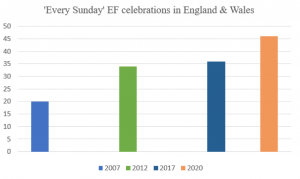

Since Pope Benedict’s motu proprio in 2007 the erstwhile ‘Extraordinary Form’ became increasingly accepted as part of the life of the Church in England and Wales by at least some of her leaders. The progress of provision for the Apostolic Roman Rite since the promulgation of Summorum Pontificum is illustrated in the above graph for ‘Every Sunday’ Masses in the same location (not counting Saturday evening Masses).

Including Sunday celebrations which take place only monthly or quarterly, the average Sunday sees 54 celebrations. (Figures for 2020 are from the first quarter, before the Coronavirus restrictions.) Given England’s high population density and concentration in urban areas it is now quite possibly the case that the majority of the population is within an hour’s drive of an Old Rite Mass on Sunday, perhaps some of the best ‘TLM coverage’ of any country in the world. Nevertheless, the Traditional Mass remains a rather small phenomenon in the life of the Church in England and Wales, and despite the establishment of shrines and chaplaincies, the attitude of the bishops in general remains no better than one of benign neglect.

COVID and Traditionis Custodes

In the Covid era the growth of the Old Rite has accelerated. The succession of lockdowns and the clerical responses to them starkly revealed the prevailing hierarchical opinion of the Sacraments as a ‘non-essential service.’ With their minimal Covid superstitions and mandatory Communion on the tongue many faithful had added inducements to approach traditional parishes for the first time. In my own diocesan parish in South London, Sunday Latin Mass averages have swelled from 134 faithful pre-Covid, to 163 during the summer of 2020 when some restrictions were lifted, to a last count of 214 following Traditionis Custodes. This represents a 60% increase in just over a year. Local sources confirm that other traditional parishes across the country have experienced similar and even greater growth.

I understand that the bishops of England and Wales were caught just as off guard by Traditionis Custodes and its severity as most traditional Catholics were. The decree’s immediate effect was received with particular shock by members of the Bishops’ Conference where decision-making tends to be cautiously bureaucratic, compromising and keen to avoid any kind of strident judgement that would upset the precarious post-conciliar status quo. However, in less than 24 hours after the promulgation of the Motu Proprio the bishops were issuing a response. Nearly every bishop with diocesan Old Rite provision granted initial permission. The Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster Vincent Nichol’s response was fairly typical. His closing note read:

“In my judgement, these concerns do not reflect the overall liturgical life of this diocese. They are, however, warnings of which we should be on our guard.”

Despite the widespread episcopal permission and extension of dispensations to traditional parishes there is much episcopal hedging overall. Many permissions have been temporarily granted until the end of the year. The bishops will be discussing the motu proprio this autumn as August is usually the time of the year when they take some holiday. Generally, England’s bishops do not like to ‘rock the boat’ and many of them are former colleagues of masterminds and enforcers of Traditionis Custodes: Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments Archbishop Arthur Roche, former bishop of Leeds and protégé of former English primate and ‘St. Gallen Mafioso’ Cardinal Cormac Murphy O’Connor. Most English bishops see themselves as loyal ‘moderates’ under Pope Francis, keen to follow his Pontifical programme, and advance their clerical careers, but not to alienate a vibrant group of their flock. In a somewhat typically English way, they will likely look to delay their response, prevaricating to see how other bishops respond, how Pope Francis’ papacy develops, and how various crises in the temporal sphere unfold.

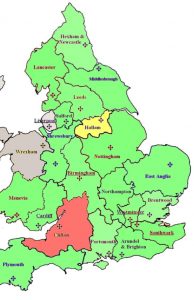

The only English casualties of the motu proprio so far have been in the diocese of Clifton: the celebration of the Old Rite Mass at Glastonbury by a new traditional Benedictine community and the university chaplaincy at Bristol. Poignantly, Glastonbury is one of the most important sites for English Catholicism. According to legend it was the site where St Joseph of Arimathea established a church and may have deposited the Holy Grail. What is certainly true is that Glastonbury was the location of one of the oldest Marian shrines north of the Alps. Alone among his English brother bishops the ailing Bishop Declan Lang of Clifton immediately implemented Traditionis Custodes and suppressed the public Old Rite Mass at Glastonbury. The LMS responded:

We are very disappointed in the response of Bishop Declan Lang to Traditionis Custodes, which seems excessively harsh and not in line with the letter or the spirit of the document. We are seeking clarification from him and await his response.

— Green = Masses continue as before

— Yellow = no Masses before or after

— Amber = some Masses suppressed

— Red = all Masses suppressed

— Grey = status unchanged/uncertain

Despite this significant blow there are many reasons for traditional communities to have hope in the resiliency of access to the Old Rite Mass in this time of suppression. I would suggest that, unwittingly, Pope Francis has just deployed a particularly effective ‘sales technique’ for the Old Rite Mass – negative reverse selling. Unknowingly using a form of reverse psychology, he has stirred up a lot of publicity and hence curiosity for the Old Rite, creating an interesting thermometer of Catholic public opinion. ‘Conservative Novus Ordo Catholics’ who are ever more disconcerted and alarmed by Pope Francis’ distinctly un-Catholic actions and statements begin to wonder: “if this unpopular pope is against the Traditional Mass what is it about this liturgy that might antagonize him? Maybe it is more Catholic?” Many of these people are now following their impulse and sampling the Apostolic Roman liturgy for the first time.

Furthermore, the survival of the Old Rite Mass in England following the 1969 liturgical reform, fitted a historical pattern of English Catholics doggedly holding onto their Catholic inheritance in the face of official persecution, or at least disapproval. In a sense we have been here before. Following more than 250 years of Penal Laws for failing to show obeisance to the ‘Anglican Settlement’ English Catholics have a corporate memory of what it is to suffer for their faith. During the lockdowns and closure of the churches there were many clandestine Masses. At this moment English Catholics can draw inspiration from the zeal and resolute faith of their ancestors in cleaving to the Mass of Ages, even ‘underground’, if need be, as the full implications of Traditionis Custodes are worked out.

Photo credit: John Aron.